Where are these jobs coming from?

As always, the jobs market remains a bit of a mystery. If you think you have an explanation for the recent jobs growth, I’m about to show you that you are wrong. (Notice I didn’t say “US jobs market”, which is already a clue that the mystery is even deeper than we imagine.)

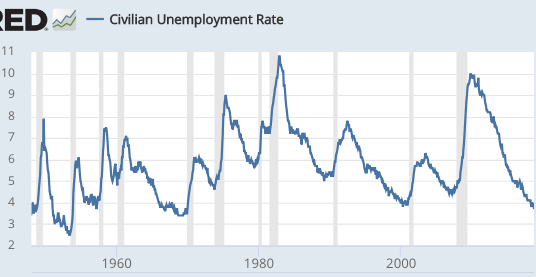

Job growth has been running at around 200,000 per month, and the unemployment rate has fallen to 3.7% (lowest since the 1960s.) It’s best to start with the accounting, which basically involves three factors: population growth, the labor force participation rate and the unemployment rate. You can use prime age labor force participation, but that makes things more complicated and also misses the growth in older workers.

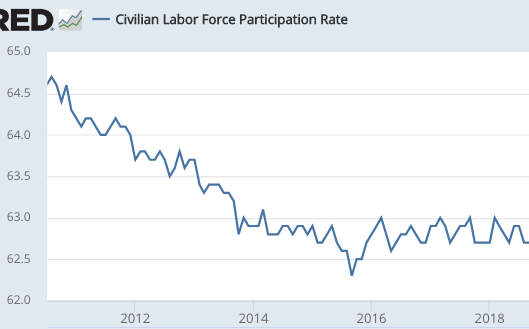

In the last few years, employment has been growing faster than predicted by growth in adult population, which can only mean that either adult labor force participation is rising, or the unemployment rate is falling. It’s not labor force participation, which was falling and then leveled off some time around 2014 or 2015 (it’s hard to be precise, as the data is noisy.)

Some people might start screaming that I’m ignoring the aging of the population. I’m not. It’s true that the population is aging, and it’s true that this means the leveling off of LFPC rate is actually a very good thing; it shows participation is rising among prime age workers. It might even show that Trump is the greatest president in history. But it does not explain the recent growth in employment. It simply suggests that we should be doing less bad than the aging alone would predict.

To fully explain the recent growth in employment (of 200,000/month) in an accounting sense, you need to look at the unemployment rate, which has fallen to shocking low levels:

A couple years ago, I expected employment growth to slow by now. The main reason I was wrong is that I expected the unemployment rate to level off in the mid-fours, and it instead fell to 3.7%. I don’t have any special ability to forecast, I was just going with the conventional wisdom:

A couple years ago, I expected employment growth to slow by now. The main reason I was wrong is that I expected the unemployment rate to level off in the mid-fours, and it instead fell to 3.7%. I don’t have any special ability to forecast, I was just going with the conventional wisdom:

In September 2016, for example, the median forecast of Federal Reserve officials was that the unemployment rate would be 4.5 percent at the end of 2018; it now looks likely to be substantially lower.

I also expected a tad worse performance for the LFPR, and rising prime age participation is part of the story. But unemployment is the big mystery that needs to be explained.

There are two possible explanations for the very low unemployment—a fall in the natural rate, or a demand shock that pushes unemployment below the natural rate. I would not completely rule out the latter, but Neil Irwin of the NYT points to a problem with demand-side explanations:

The even better news is that the last time the jobless rate was this low, at the end of 1969, it was already fueling high inflation. Consumer prices rose 5.9 percent that year. Currently, that measure is 2.7 percent.

In fairness, that 2.7% figure is consistent with somewhat of a demand boost, thus it’s not that different from the situation in 1966 (when inflation was about the same). But on balance I don’t see much evidence that this is a demand-side issue, partly because the inflation figure includes recent oil price increases, and inflation forecasts continue to run at around 2%. In a couple years we’ll have more perspective on this issue, but right now I’m going with the supply-side explanation, i.e. an unusual fall in the natural rate. Later I’ll provide international evidence for that view.

I’ve been racking my brain for reasons why the natural rate of unemployment should have fallen to perhaps the lowest levels in history (actual unemployment was below the natural rate during the Korean and Vietnam Wars), but it’s not obvious what those are. In a recent Econlog blog post, I discussed the fact that the federal minimum wage was now so low as to be almost meaningless. But that affects only a small part of the labor force. You could point to Trump initiatives like a corporate tax cut that boosted RGDP growth. But the same occurred during the Reagan boom, and yet the unemployment rate never fell below 5%, even after very strong RGDP growth spurred by tax cuts and deregulation.

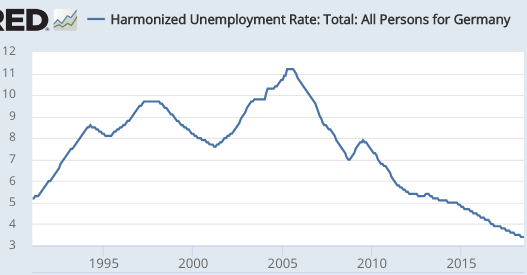

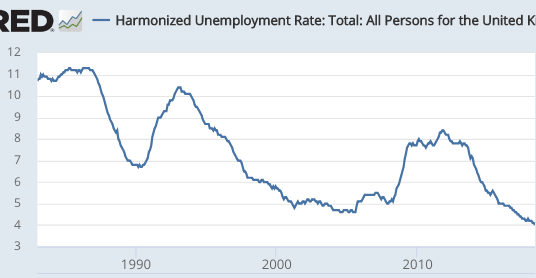

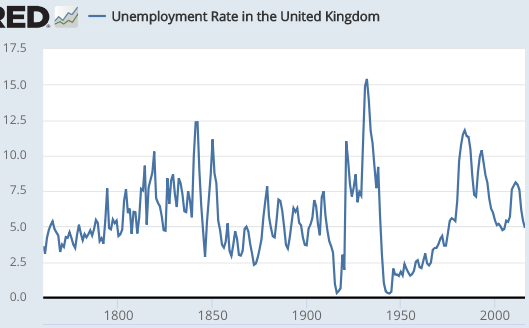

At this point I look to other countries for assistance. Europe has a very different unemployment pattern than the US. During the post-WWII boom they had an extremely low natural rate, relative to the US. During the 1980s and 1990s, their natural rate rose far above the US, even in Germany. It remains elevated in France and southern Europe, but has recently fallen in the UK:

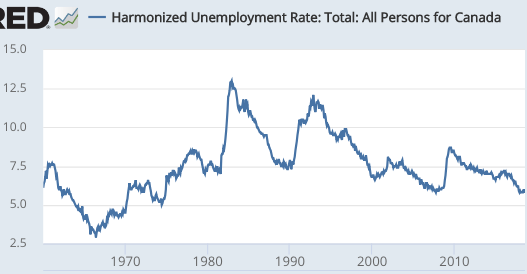

So there is modest evidence that this phenomenon of falling natural rates is affecting other countries. Canada is a bit more ambiguous, with a higher natural rate than the US, but some evidence of a downward trend since the 1980s:

So there is modest evidence that this phenomenon of falling natural rates is affecting other countries. Canada is a bit more ambiguous, with a higher natural rate than the US, but some evidence of a downward trend since the 1980s:

I don’t have a good explanation for why Canada has a significantly higher natural rate than the US. It may have a bigger welfare state, but the same is true of the UK and Germany.

So unemployment remains something of a mystery. By the end of the Obama administration, unemployment had already fallen below the lowest levels of the Reagan boom (to 4.6% on November 2016), despite slower growth and less business friendly regulation. So while I would not rule out the importance of supply-side policies, especially the tax cuts, I think a portion of the story remains unexplained.

Note that Germany and the UK have seen their unemployment rates fall dramatically to the 3.5% to 4% range, despite tight fiscal policies. So Keynesians should be just as confused as supply-siders. Fiscal policy has also gotten tighter under Abe, and Japan’s unemployment has fallen to 2.5% (although they’ve traditionally had very low unemployment.)

Before commenting, think about how your explanation fits the international pattern, and also the US time series going back to the 1940s. It’s harder than you think. BTW, we won’t be able to figure out the trend rate of growth in RGDP until we can observe a year of two of RGDP growth with a stable unemployment rate. The wait continues. . . .

If you want an even longer time series, there’s a UK graph going back to 1760, when unemployment was 3.63%. (Love that precision!)

Tags:

5. October 2018 at 09:50

I have no idea, I just want to pose a question. Is there any research or speculation that shifting generational cultural attitudes might help determine the natural rate of unemployment? In a similar way to changes in matching technologies?

I recall that it has been shown (I can’t easily find the reference right now) that coming of age during or near recessions has persistent impact on their perceptions of risk, employment etc. So global recessions might cause correlated changes in national natural employment rates years later.

Plus Western cultural movements are pretty highly contagious anyway e.g. Reagan / Thatcher ; Brexit / Trump (yes, I know the causes of Brexit and Trump were in some ways very different), and I would expect to be more so in the internet age.

5. October 2018 at 10:11

Technology enables more flexible work schedules, so people can more easily do things like 1) not give up their job when a spouse is promoted and may have to move (or the spouse may not have to move!) or 2) find a tele-commuting job from a company outside of their area.

Also, though I am less sure how this applies to other countries but it probably does also apply to China at least, it seems to me that factors spurring the two-income trap in which real estate prices, daycare costs, etc., have increased. In addition, lower birth rates may make it less financially attractive for a parent to stay home, and the amount of time invested into a career by a woman having a child at a later age may make it harder to give up the financial rewards of returning to work. Even if someone is a stay-at-home parent, they may still be technically employed through various home businesses.

5. October 2018 at 10:24

Couple thoughts: the prime age numbers are more meaningful, cuz these folks are expected to be in the labor force come hell or high water. Enough younger and older people have the flexibility to move in and out of the labor force to create annoying noise there.

From peak to trough, the US economy shed 8.8 million jobs in just over 2 years (Jan 2008 – Feb 2010). There was a lot of talk at the time about these being ZMP jobs that wouldn’t come back. That take hasn’t aged so well.

You can estimate the number of “net new job seekers” annually from demographic data. Not surprisingly, that number has been going down (boomer cohorts retiring).

If we assume this number is 1.2 million and add these people to the job losses between 2008 and 2010, that’s 11.2 million jobs behind trend by Feb 2010.

In the past 8.6 years, the economy has added 19.8 million jobs. Again, if we assume 1.2 million net new job seekers per year, that means jobs for them plus 9.5 million of the people who lost jobs between 2008 and 2010.

Which means we are down to the last 1.7 million of folks who have yet to come back. Maybe most of them won’t. (If we assume 1.4 million net new job seekers, though, that suggests there are still 3.8 million of these people out there.)

Yes, LFPR numbers are murky and natural rate of unemployment stuff is guesswork, in which case perhaps the economics profession should give greater weight to wage growth as an indicator of labor market tightness and inflation as a sign of economic overheating.

By the way, low unemployment has always been a cause for celebration among Democrats and consternation among GOP business owners- at least before Trump.

5. October 2018 at 10:31

Also Scott, thanks for writing on this topic, which is bizarrely under-covered among economists.

5. October 2018 at 10:37

FYI, Canada calculates unemployment differently than in the US. Essentially, you need to substract one percentage point from Canada’s to compare to the US.

See, e.g., https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/180810/dq180810a-eng.htm

“Adjusted to the concepts used in the United States, the unemployment rate in Canada was 4.8% in July, compared with 3.9% in the United States. In the 12 months to July 2018, the unemployment rate declined by 0.5 percentage points in Canada and by 0.4 percentage points in the United States.

The labour force participation rate in Canada (adjusted to US concepts) was 65.3% in July compared with 62.9% in the United States. On a year-over-year basis, the participation rate decreased by 0.3 percentage points in Canada, while it was unchanged in the United States.

In July, the US-adjusted employment rate in Canada was 62.2%, compared with 60.5% in the United States. On a year-over-year basis, the employment rate was unchanged in Canada, while it increased by 0.3 percentage points in the United States.”

BTW, my hunch is that Canada’s larger labor force participation rate, larger employment rate and unemployment rate are linked to the larger proportion of immigrants in Canada.

5. October 2018 at 10:39

What do you think about this thread by Krugamn, aiming at Tyler Cowen ?

https://twitter.com/paulkrugman/status/1048198986371399680?s=21

5. October 2018 at 10:43

An observation which makes the fall in unemployment even harder to explain: lower NGDP/inflation rates should really make wage stickiness a bigger problem than it would otherwise be.

It also didn’t occur to me until now how much worse the demand side imbalance must have been in the Great Recession compared to the early 80s recession given the difference in the “natural rates” between those times. The economy was atrociously bad back in 2010.

I wonder if terrible recessions push cultures towards taking whatever job someone can get as well as towards working if jobs are available. Note Canada did not have such a bad recession in 2008-2012, while Japan has had an even lower unemployment rate than the US since their bad recessions.

5. October 2018 at 10:50

Does the same story appear if we look at the broader measures of unemployment and underemployment? I keep seeing articles about how the gig economy seems to be surprisingly resilient the current economic expansion, as opposed to just a reaction of desperate people to the last recession. Perhaps there is greater scope for people to work part-time, flexible hours jobs than in the past, and that accounts partly for a lower rate of unemployment before inflation rises too much?

5. October 2018 at 10:53

I guess the explanation I just put forward would be a sort of supply-side shift enabled by technology. Essentially, apps and smartphones enable more people to work who don’t want a full-time job and also don’t want to have to conform to the crazy scheduling of a lot of low-wage employers.

5. October 2018 at 11:30

In periods of “full-employment” there will still be churn. Jobs destroyed in one industry, with jobs created in others, and some amount of frictional unemployment. People who are between jobs, but it might take them a couple of months to find the next job.

Looking at initial jobless claims. Last report was 207,000, and the lowest since the 1960s. But this number is not adjusted for population growth, so over time we should expect to see the line trending upward by 2%-ish per year. People who are already employed are not losing jobs. The “churn” is low.

Another thought, as information technology improves, people between jobs should be forced to spend less time looking, as they will have better information on who is hiring.

5. October 2018 at 11:43

I wonder if it doesn’t have something to do with let’s say “marginal” people dropping out of the labor force all together. The ranks of the homeless have grown incredibly it seems, judging by all the tent cities you see on the west coast these days, plus the non-homeless but non-labor force opioid addicts. You’d have to sit down and think out some plausible magnitudes and see if it really makes sense, but it seems to me if a few million people who in a previous era would have been chronically bouncing between jobs (boosting unemployment) exit the labor force to live in tents/do drugs/take disability, that it could be worth a few tenths of a percentage point of unemployment. 4 million additional people on disability just since 2011.

5. October 2018 at 11:52

RE: a fall in natural rate of unemployment – we know that labor force participation (prime age and otherwise) fell during the recession. We know that the rates of disabled etc. rose. I haven’t seen a great dissection of people who are not in the labor force (school, disability, etc.), of course. But in general we know that labor force participation has been decreasing (both prime age and otherwise) in a long-term trend.

At the peak of 1990 and 2007 booms, prime age employment ratio was about 80%. It was almost 82% in 2000, and it is 79% today. If the prior era’s labor force included people that would NOT be in the labor force today, then the natural unemployment rate would drop. Perhaps the overall

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lu4t

So really doesn’t it just come back to the drop in labor force participation rate? You are talking about people who may have been working while disabled that completely dropped out during the recession, people who now are more likely to be in graduate school, and the unqualified people who have just dropped out completely, right?

5. October 2018 at 12:03

Matthew and Derek, Yes, those are plausible suggestions. I think a mix of societal and technological factors may have played a rule. Think how Uber makes it easier to get a job, compared to when we had the taxi cartel.

Brian, I agree that prime age is more meaningful for certain contexts. But in this case it doesn’t matter. Prime age participation is a bit better, but prime age population growth is slower. The two offset. So you still need to focus on the unemployment rate. That’s added at least a million extra workers since the election, probably more like 1.5 million.

LK, Thanks, I should have known that, it makes part of the mystery disappear.

Cameron, Yes, and the low current rate also undercuts “hysteresis” theories.

Burgos, Good point, I recall that U-6 is not at such low levels, another thing I can’t explain. With a labor shortage, why can’t people find more hours? Is it more burdensome government regulation on full time jobs?

Doug, Yes, roughly 5 years ago I started blogging on layoffs being unusually low, even while unemployment was high. Adjusted for population, they are the lowest ever.

Justin, That’s possible, but probably not enough to explain the whole story.

5. October 2018 at 12:06

Cloud, I agree with Krugman that the high unemployment was a demand side problem. I think that’s been confirmed.

5. October 2018 at 12:50

OK Scott, I’m just saying that from a surface perspective, we had job losses that dwarfed anything post-WWII followed by a jobs recovery much less robust than previous recoveries (we barely scraped 3 million new jobs per year at its peak.)

Just from this, we should realize there was a huge reserve labor pool, millions and millions more potential than actual workers. You don’t need to muck around with LFPR and unemployment numbers to see this.

Clearly, Tyler’s ZMP hypothesis from 2010 has been shredded. In retrospect, it looks awfully callous.

If the unemployment numbers and LFPR trends have you scratching your head, just step back and look at the larger employment numbers.

Or, as I said before, give more weight to wage increases as an indicator of labor market conditions.

5. October 2018 at 12:59

One more thought: those 19.8 million new jobs since Feb 2010 are 100% in the private sector. Of course there are ZMP workers, but I suspect it’s easier to pull this off in the public sector. The percentage of workers in the US that work for the government is currently 14.99%. You have to go back to December of 1957 to find a lower percentage than that.

5. October 2018 at 13:49

Internet (and lower transportation cost) have intensified individual’s comparative advantage.(?) (especially for marginal workers)

5. October 2018 at 13:57

I also like this blog’s articles of “international economics” tag.

5. October 2018 at 14:41

Brian, You said:

“Just from this, we should realize there was a huge reserve labor pool, millions and millions more potential than actual workers. You don’t need to muck around with LFPR and unemployment numbers to see this.”

Actually you do. There are a number of very long term changes in labor force participation that are very important. Male participation has been trending downward since the 1950s. If you ignore this, you’ll get deeply misleading results.

Obviously I agree with you that there was a lot of excess unemployment after 2008, that’s why I got into blogging.

5. October 2018 at 16:35

Yes, and you did not even mention Japan!

163 open jobs for every 100 jobseekers in Japan and yet real wages are falling at latest report.

I used to say the Phillips Curve was dead and prone, but in the case of Japan I would say it is upside down.

Well, the old story was that big bad unions had a lot of power and budged up wages and then Big Steel and Big Auto just raised their prices so you got higher wages and prices despite mediocre unemployment rates.

Perhaps the macroeconomics profession has been compromised and co-opted by financial elites. A framework evolved in which the only way to fight inflation was to beat up on workers. This had the pleasing result of shifting income shares upward away from the laboring classes.

There is much in this world that can be explained by vulgar Marxism. Unfortunately Marxist medicine is usually poison.

But Marxism has its moments as a diagnostic tool.

5. October 2018 at 19:25

NGDP for 2018 is now at 5.4% on hypermind, but how much of this is sustainable? is there any use in having a longer term forecast (say avg NGDP growth through 2021) on hypermind?

bond yields, despite their recent rise, would seem to imply that 5.4% NGDP growth isn’t going to continue for the next few years…?

5. October 2018 at 19:44

I’m not too surprised. I considered full employment to be somewhere between 3.8 and 4%.

I consider the recent labor shortage to be due to employers remembering the lessons of 2008, and not raising wages to more than levels they can afford in a recession.

As a rule, the labor market has less job churn than it did in the old days. Fewer hires, *much* fewer fires.

Possibly the Internet. The Internet may have increased the average duration of unemployment by increasing the amount of BS job applications and made it more difficult to hire new workers (and, thus, increased the risks of firing old workers).

5. October 2018 at 20:46

Could it be a problem with how the labor force participation rate is calculated? I mean if you retired (maybe not 100% voluntarily) some years ago you would be out of the labor force immediately- but not ‘unemployed’ the way that is calculated. And the unemployment rate goes up just a bit because you are not in the labor force with a job anymore. Maybe you aren’t actively looking for any employment so you remain out of the ‘labor force’. But then there is an offer to do some consulting work type thing at close to your old pay rate and you take it. Now suddenly you are back in the labor force and employed, but only back into the ‘labor force’ at that exact time the job offer was made and you accepted it. So the unemployment rate comes down just a bit even though technically you have never been unemployed while you were sort of ‘retired’.

I think there were a lot of people similar to this. They could also be students who looked at the job prospects and decided to continue school, or parents who decided it made more sense to look after their children rather than search in a crummy job market. But in any case, they will be people who can afford not to work for some period of time for whatever reason. People like this will not be counted as in the labor force until they take a job. Even though they probably should have been.

I think Brian Donohue is right.

5. October 2018 at 23:29

– (Un-)employment goes up and down with the increase and decrease of credit.

– Off topic: 3 videos on the housing crash in Australia:

http://digitalfinanceanalytics.com/blog/60-minutes-segment-now-on-youtube

– In one suburb of Sydney the amount of foreclosures is up over 600%. Median home price (in that same suburb) is down from about AUD 1.2 million to about AUD 1 million.

– Home prices can go down some 40 to 50%.

6. October 2018 at 03:37

Why has the natural rate of unemployment fallen? Possibly a reaction to the crisis: that is, people are at the moment possibly grateful for a job and are not going to risk it by demanding excessive pay increases. Possibly the same phenomenon was evident in the 1950s and 60s: that is, most employees then had memories of the 1930s, and were grateful for a job. Then come the 70s and 80s, that lot retired and we got a more happy-go-lucky / irresponsible collection of workers.

6. October 2018 at 05:33

Scott,

Theory – (as suggested by Jerry Brown) People are more likely to categorize themselves as unemployed if they have recently held a job then if they have been out of the labor force for an extended period of time and begin looking for work. If correct this means.

1) Unemployment is over-reported when the economy is declining and under reported when the economy is growing (rising employment.)

2) Current numbers understate both unemployment and the LRPR.

I’m not sure I would entirely buy into Winship’s work on the male participation rate. Certainly there has been some shift in who stays at home, but I think recent trends have a lot more to do with the male ego not wanting to admit they have no job prospects then with any long term trends.

Also if you look at age 25 – 54 employment to population, it is still 2 to 3 million below peak. I think one is hard pressed to come up with non-cyclical reason for that decline, which implies there is still substantial runway for employment growth.

One other interesting data point is that while the number of unemployed is dropping. The number of unemployed looking for work now is actually marginally up over the last year. Given the job growth, this also suggests that there are many people who are going straight from not participating to employed.

6. October 2018 at 06:00

Has the gig economy and contracting grown in UK and Germany like it has in the US? Not only do the gig economy and contracting offer alternative employment for those that haven’t been matched to a traditional job, aren’t the wages also more flexible? Think of Uber surge pricing, which allows wages to fluctuate with demand.

6. October 2018 at 07:00

‘Western cultural movements are pretty highly contagious anyway e.g. Reagan / Thatcher ; Brexit / Trump (yes, I know the causes of Brexit and Trump were in some ways very different)…’

Actually, Matthew, they’re pretty much (broadly speaking) the same. The last line in Thomas Sowell’s greatest book, ‘Knowledge and Decisions,’ said it perfectly; what ordinary people need to have a satisfying life is to be ‘free from the rampaging presumptions of their betters.’

I’ve been waiting for Britain to rebel against the EU since it was decreed that they could no longer sell bananas by the pound. A permanent governing class that petty was asking for it. Now they’re getting it.

6. October 2018 at 07:37

It seems that in just about every US downturn and recovery, people overestimate supply-side side factors when accounting for unemployment, and underestimate the eventual strength of the recovered economy.

As I’ve been saying for some time, monetary policy is still too tight and the unemployment rate will continue to surprise on the way down until people understand this. A bit looser policy would get us to that lower sustainable rate of unemployment sooner.

Look at market reactions at the end of last week. Good jobs data sparks fears of tighter money, driving down the stock market. My contention is that we should still focus on creating a steeper yield curve. Inflation should not be a concern.

I think we’re coming out of something like a slight J-curve, regarding productivity, and that looser money will unleash a productivity boom. I think this is true in most of Western Europe and even in Japan and China, to lesser degrees.

As I always say, I don’t claim that they’re no structural factors at play. I just think many central banks are still riding the brakes. Real growth potential is underestimated.

6. October 2018 at 10:19

I remember reading a few years ago that one of the unintended consequences of Obama Care was that some industries were moving toward more part time help to avoid having to pay for health insurance, especially the hospitality industry. In fact, hotel workers in Boston are on strike right now because most of them have to work two jobs due to this. I assume that if you move your full time workers to part time, you have to make up the lost hours somewhere, and that two part time workers might be cheaper than one full-time worker.

6. October 2018 at 10:27

Why shouldn’t we believe the natural rate of unemployment to be the rate that we saw in the late 90’s? I mean, that was the last time we had a tight enough labor market to see rising wages. It was 20 years ago, but it is still the best historical example that we have.

6. October 2018 at 11:23

Jim, I agree that NGDP growth will gradually slow from 5.4%, perhaps it already has. (The second quarter was over 7%, and that figures into the 5.4% prediction.)

Harding, You said:

“I considered full employment to be somewhere between 3.8 and 4%.”

You might be right, but keep in mind that it’s not a fixed number. It was over 6% in the early 1980s.

Willy, Keep predicting it, eventually it will happen.

dtoh, Some good points, but regarding this:

“Also if you look at age 25 – 54 employment to population, it is still 2 to 3 million below peak. I think one is hard pressed to come up with non-cyclical reason for that decline, which implies there is still substantial runway for employment growth.”

Keep in mind that male labor force participation has been declining since the 1950s, so I don’t think it’s just the cycle.

https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/economists/dotsey/prime-age-male-labor-force-participation.pdf?la=en

Having said that, it may be partly due to the cycle, for reasons you indicated.

Also note that some of the stuff you mention also applies to other business cycles, and thus doesn’t really explain the unusually low natural rate in this cycle. (Not saying you claim it does.)

Mike, You said:

“A bit looser policy would get us to that lower sustainable rate of unemployment sooner.”

Unfortunately, there is not one successful example of this in all of US history, so it’s just wishful thinking. Your suggestion was tried in the late 1960s—how’d that work out? It failed again in the late 1970s and the late 1980s. Yes, I know, this time is different.

David, Good point.

Burgos, When wage growth is rising, unemployment is generally below the natural rate. We won’t know the natural rate for a few more years. BTW, unemployment is currently below the rate of the late 1990s. So if that’s the natural rate, we’re in trouble.

6. October 2018 at 13:47

Scott,

I see little harm in the Fed shifting regimes to NGDPLT, at 5%. In that case, I think things really would be different.

6. October 2018 at 17:34

Let the good times roll.

What America needs is full-tilt boogie boom times in Fat City, and let it ride ’till the cows come home.

The sniveling weenies at the Fed, and their squeamish fetishes regarding prosperity and inflation, are a menace to progress and even our social fabric.

I put it mildly.

6. October 2018 at 18:11

@Scott:

– Did you even bother to watch the videos ? When are going to acknowledge your mistakes ? When your Market Monetarism buddies are going to talk about it as well ? Or when it’s making headlines in the US (as well) ?

– Don’t look at the (N)GDP because GDP is (exremely) flawed. GDP counts housing twice. Once when a house is being build and for a second time when a person lives in it. Then it’s counted once more every year.

– Steve Keen (using his own metric) sees a US already in a recession and an Australia that’s already MUCH deeper in a “recession” and very close to a contraction in the amount of credit.

– There’s one metric that predicted the US and australian housing bubble and crash well in advance. Between 1968 and 2000 – on average – (median) household income in both countries kept growing. NOT in a nice straight line but the overall direction was up. But in both countries this income didn’t go up anymore after the year 2000 while at the same time home prices kept rising. This divergence is a GOOD recipe for disaster in both housing markets.

6. October 2018 at 18:41

I think Brian Donohue is right. The unemployment rate isn’t so reliable anymore. People these days have much more flexibility to move in and out of the labor force.

In Germany, for example, there is a big trend towards disability. One is no longer unemployed these days but rather temporarily disabled.

6. October 2018 at 19:12

The Wikipedia article on real wage rigidity gives the implicit contract, efficiency wage and insider-outsider theories.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_rigidity#In_the_labor_market

Efficiency wage and implicit contract follow from turnover and monitoring costs. Anecdotal evidence says these costs have been reduced considerably due to IT investment. The monitoring cost decrease have also affected UK and Germany.

However, lower monitoring costs do not entirely convince me. Retail and warehouse employees are monitored more than the 70’s, but these employees were always highly monitored for productivity. Same with manufacturing.

Instead, competition may have broken the “insider-outsider” wage misalignment. As mentioned here, Uber broke the taxi cartels. There was also the Big Three/UAW and foreign competition. I have personally heard from blue-collar workers that “you had to know someone” to work in the Ford and GM plants in Atlanta.

In theory, protected companies would ruthlessly get rents while setting wages at market level. In practice, CEOs may have had different incentives than shareholders. Often, insiders gradually increased their wage premiums. So 1970’s GM overpaid for new market analysts or engineers, partly to justify insiders’ current salaries. The overpayment led to more applications and higher unemployment.

The harsh “zero-based-budgeting” of Heinz and Anheuser-Busch give recent examples of how hard it is to break internal bureaucracies in successful, rent-earning companies. Even if CEOs had financial incentives aligned with owners, insider CEOs may not want to undergo these harsh steps.

I do not know about UK and Germany, but they have also been exposed to more competition.

6. October 2018 at 22:18

MIke, Sure, but the current regime requires a different policy. The point is to have a stable policy, whatever regime they choose. If they want to target inflation at 2%, it makes zero sense to now adopt a more expansionary policy. It will lead to recession.

I’d be thrilled if they shifted to 5% NGDPLT.

Willy, Australia’s one of the faster growing developed countries. I don’t watch “videos”. I look at actual data.

6. October 2018 at 22:32

I would like to agree with Brian Donahue but the U.K. Labour Forfe Participation Rate would seem to argue against that thesis.

https://tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/labor-force-participation-rate

6. October 2018 at 22:41

US prime age LPFR solidly average, half way between N Europe and Mexico.

https://data.oecd.org/emp/labour-force-participation-rate.htm

7. October 2018 at 06:50

How, actually, is housing counted in NGDP?

Is a value attributed each year to the “housing services” delivered?

Or it once, at completion of construction? (which should be the NPV of the housing services, more or less)

7. October 2018 at 07:49

– I also look at the data and then one can see that Australia has a housing/credit bubble. Australia’s debt to GDP ratio is the (second) highest in the world. The videos are very instructive because then the people have to squeeze lots of data into a few sentences/sound bites.

– Australian data has been analyzed by one Martin North of “Digital Finance Analytics”. The link (I provided above) opens Mr. North’s website/blog. He regularly posts videos and charts. And Martin North uses data from e.g. the ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) and the australian federal treasury. No need to “dig up” that data yourself. Just visit Martin North’s website/blog and the truly excellent australian website http://www.macrobusiness.com.au. They will do the “heavy lifting” of sifting through/analyzing the data for you.

– Martin North uses a number of proprietary models to calculate and to draw up his charts. One model told North that already some 20% of australian households (= about 1 million households) are already in (severe) “mortgage stress”. And the official recession (think: the flawed (N)GDP) hasn’t officially begun yet. But that’s something the ABS data won’t tell you.

– Building a house is production and is therefore included into GDP. After that the NBER assumes that the homeowner pays OER (Owners Equivalent Rent) every year. And the NBER adds that OER to the GDP. As if OER is some kind of “production”. That way the NBER miscalcutales/overestimates GDP. Using this flawed metric the NBER concluded that the US recession began in november 2007.

– Whereas three other people (Steve Keen, Charles Biderman and John Williams) concluded that the recession in the US already began in (early) 2005/2006. Keen looks at the amount of credit, Biderman uses online data from the US Treasury (updated weekly) and Williams tracks the changes in the calculation of GDP and then re-calculates that to the old GDP model.

– Keen recently warned that Australia is already (deep) in a recession for more than a few months.

7. October 2018 at 08:22

I agree that the late 90’s saw rising wage growth, and somewhat higher inflation. However, my recollection was that once wages started growing, productivity growth was unexpectedly high. I guess the point was just that the late 90’s I think represents the best approximation of the overall dynamics of the current US economy near full employment that we have. I also suspect that shale oil and electric vehicles are having some impact on inflation and the natural rate. The fact that liquid fuel is no longer such a firm constraint on economic growth has to be playing some role in what is going on.

7. October 2018 at 09:41

James, Really interesting data. Look at how much the US/France comparison shifts when you go from 15-64 to 25-54. (Note that France has an extra 5% unemployed, so their employment/pop. ratios will be lower than labor force participation.

Willy, The Aussie economy is growing at over 3%, and is expected to expand 2.8% in 2019–it’s one of the fastest growing developed economies in the world. BTW, I’ve never suggested that Australia will never have a slump, just that all the previous bubble predictions have proved laughably off course. But keep trying, someday it will come true. Who knows, maybe next year.

Bill, Both, as with any other large industrial “machine” (but not autos or home appliances, which are viewed as consumer goods, not investment goods.) Yes, it’s very arbitrary. This suggests we might want to focus more on national income net of depreciation.

Burgos, In retrospect, money should have been a bit tighter in 1999-2000 and a bit easier in 2001-02.

7. October 2018 at 10:06

Does anyone know if there is a post where prof. Sumner discusses what the best level for the NGDP growth rate to be? I think 6% is better than 5%, assuming that is politically feasible. Tight labor markets are important in all sorts of ways, so I think a higher NGDG than 5% would be good. When people are confident that they can always find a job, they are much more supportive of libertarian policies.

7. October 2018 at 12:26

Scott,

Thanks again for a great post and comments.

Here’s what I’m saying: there is a category of people in this bucket: “I had a job a year ago, but now I’m involuntarily out of work”.

During recessions, this bucket swells to millions of people. In 1982, 2.5 million jobs were lost, so there were millions of people in that bucket at that time.

But in 1983, 4.9 million jobs were added, so presumably, this bucket went back to whatever “background” or “normal” levels is.

In 2008-09, 8.8 million jobs were lost. But no snapback- just 2.4 million jobs added in 2011.

Over a 2-year period, something like 10 million people landed in this bucket. Long-term LFPR trends aren’t particularly useful in explaining this dramatic occurrence.

And the return of most of these people explains continued strong, employment growth through 2018. So I’m glad we didn’t act on the ZMP hypothesis. And I’m not even sure if the return has run its course yet. Where’s the wage growth?

7. October 2018 at 16:02

“Glassdoor, an employment site, says average pay at U.S. fulfillment centers has been $13 an hour, according to nearly 900 people who submitted their data to the site.

Amazon’s pay is significantly above the $10.28 an hour that the typical retail worker makes, but it’s less than the $15.53 that a median warehouse employee is paid, according to Labor Department data.”—WaPo today.

There is some commentary about “labor shortages” in the US. But if you look at job ad sites, the prevailing wage for semiskilled labor bunches around $13 an hour, and for pretty hard work, such as working in a restaurant or warehouse.

I suspect that much of the complaints about labor shortages are from companies that cannot afford to pay the prevailing rate for semiskilled labor.

There once was a pillar in certain financial circles that recessions are not so bad as they flush out weakling companies.

Perhaps the shoe is better on the other foot. A sustained economic recovery flushes out weakling companies that cannot pay prevailing wages, leaving behind only those sturdier outfits.

Some very high-cost rental areas, such as along the West Coast, may have to pay more for labor.

7. October 2018 at 18:51

Shouldn’t the question rather be: Where are the people coming from?

8. October 2018 at 03:06

Think I saw somewhere that the employment ratio for working age people was up 0.2 points in September. That’s about 400,000 people added to the workforce.

8. October 2018 at 08:24

New deal with Mexico and Canada.

Lowest unemployment rate since the dawn of time.

Kavanaugh as Justice of the Supreme Court.

What a week for Donald J. Trump.

8. October 2018 at 10:18

Looking at bls.gov, total employment in January 2008 was 138,419,000. Today it’s 149,500,000. 8% total growth over 10.75 years. Anemic. (some people who are better at marketing would say “sad” instead of anemic).

8. October 2018 at 10:29

I believe it’s geography/migration. More Americans than ever live in major metros and own cars, meaning they have a lot of job options. These metros are not very differentiated from each other.

By contrast, in the past it seemed there were always many cities undergoing large structural convulsions due to technology or trade changes: e.g., the switch from integrated mills to electric arc furnaces in steel. These convulsions would go on even when the US economy was doing great.

On page 2 of this report, for instance, they have the Pittsburgh unemployment rate against the US one. The two track each other for all of 1970 to present, but in the 1980s you have the convulsion caused by the steel industry shrinking/retooling.

https://ucsur.pitt.edu/files/peq/peq_2008-12.pdf

8. October 2018 at 11:43

‘– Steve Keen (using his own metric)…’

He’s still doing that, huh?

8. October 2018 at 12:03

Here are some ideas. First, the OP refers to the ‘natural rate of unemployment’, but what does that mean? Aren’t we talking about the NAIRU? Which itself is a very strange and possibly meaningless concept. So related to this, when was the last times we credibly got down to the NAIRU? 90s and 60s, right? A different question to ask is, why would expect the NAIRU to be at all similar in the very different conditions of these eras? Maybe unpredictability is what we should expect.

Here are two ideas for why the NAIRU could be lower today. First, search costs are lower due to internet technologies. Not just gig economy stuff, but basically looking for a full time job is vastly easier. Second, companies have basically won the battle against labor. Instead of increasing salaries in tight labor markets, they are increasing bonuses or other fringe benefits that are easy to pull back later. And bonuses are especially effective at attracting labor in a tight market without driving up a companies average cost of labor too much.

8. October 2018 at 14:42

Everyone, ROFL at all the Trumpistas who said the 4.6% unemployment rate under Obama was meaningless, and “didn’t I know that the actual rate of unemployment was 40%”, are now trumpeting the 3.7% rate as legit. Reminds of of the people who “believe the women” when the woman accuses a guy in the other political party. Even Mencken would be speechless faced with modern America. I’m pretty cynical, but I still can’t keep up with reality.

Burgos, You said:

“Tight labor markets are important in all sorts of ways, so I think a higher NGDP than 5% would be good. ”

That’s a non-sequitor. Higher trend rates of growth for NGDP don’t make for “tighter” labor markets.

Brian, Don’t compare us to the 1980s, when the labor force was growing very rapidly. As for the nominal wage growth, it is accelerating, but not yet to worrisome levels.

dtoh, Monthly numbers from the household survey are not meaningful; you want to look at year over year changes. Or the payroll survey. The household survey is super noisy.

Christian, Wait, you are treating the Canada deal as a win for Trump? Have you no shame?

Bill, Why do you say that? It doesn’t seem anemic to me. You might be right, but I don’t see the logic.

mpowell, You said:

“Aren’t we talking about the NAIRU?”

No.

8. October 2018 at 15:00

A higher NGDP growth target as part of level targeting would allow the bank more room to let the economy run hot before trying to slow down growth. I guess that I am thinking that higher inflation in most cases implies a lower unemployment rate, especially because nominal wages matter and inflation too low introduces a lot of friction in labor markets. I also think that higher inflation, up to a point, is a good way to drive inefficient companies out of business, which I also suspect is a function positively correlated with faster growing nominal wages.

9. October 2018 at 05:24

Two possible explanations:

1) ICT has greatly improved the process of job-matching, both locally and nationally. Workers and firms find it easier to find each other. This should push down the ‘natural’ rate of unemployment in any time and place.

2) Disability rates have gone up a lot compared to a generation ago. Some unemployment used to be people who were able to work, but only contingent on it not being too physically onerous. Most of these people are now officially classified as disabled, and are therefore out of the labour force.

9. October 2018 at 12:33

For higher “fixed cost” share of marginal labors, intensified comparative advantage (by ICT? internet? lower trasnportation cost?) especially enables marginal people’s labor participation.(higher change rate)

(Unemployment rate is the index value of marginal people)

9. October 2018 at 16:39

Scott,

You said, “Everyone, ROFL at all the Trumpistas who said the 4.6% unemployment rate under Obama was meaningless, and “didn’t I know that the actual rate of unemployment was 40%”, are now trumpeting the 3.7% rate as legit.”

Since I probably had the most say on this topic, let me respond,

1) Trump said the unemployment rate was 18 to 20% not 40%

2) Unless you were being deliberately obtuse, it was obvious Trump was not talking about U3.

3) Taking into account the 12 million person drop (adjusting for demographics)after Lehman in labor force participation, a claim of 14% unemployment would not have been far off.

4) Relative to the accuracy of most professional economic pundits and forecasters, an 18% claim against an actual number of 14% would have to be considered exceptionally accurate.

5) If you assume even modest politically feasible supply side improvements such as tax reforms, a slight increase in the social security retirement age, and the curtailment of government subsidization of student loans, 18 to 20% seems highly accurate.

6) When Trump made the 18 to 20 claim, U3 was 5.6% not 4.6%

7) U3 numbers have to evaluated in the context of the economic cycle. 8 years after Lehman with low LFPR and unsteady RGDP, 5.6% is an awful number. (Thank you Ben Bernanke.)

8) Agree U3 is not a great proxy for evaluating economic performance, but 3.7% tells us something different is happening.

9) I’m not a Trumpista.

10) Just because an argument is made by someone (Trump) that you don’t like, doesn’t mean it’s wrong. You’ll handicap yourself intellectually if you use ad hominem standards to evaluate an argument.

10. October 2018 at 05:12

Scott,

I’m confused as to why you want to speak so much about what Fed policy should be within the inflation-targeting regime. It is an obviously flawed regime. You even have an NGDP futures market, though not one that offers longer term forecasts. Is the lack of longer term contracts the issue?