What would core PCE futures price targeting look like?

Here’s a conjecture. Core PCE futures targeting would look a lot like NGDP targeting. Not NGDP futures targeting, rather it would look like a monetary policy that stabilized current NGDP. In other words, a lot of the volatility of core PCE inflation is due to NGDP volatility, with NGDP impacting core PCE with a lag. Alternatively, stabilizing NGDP growth would provide quite stable core inflation, indeed even more stable core inflation than what we had during the “Great Moderation”, a period when the Fed was actually trying to stabilize inflation.

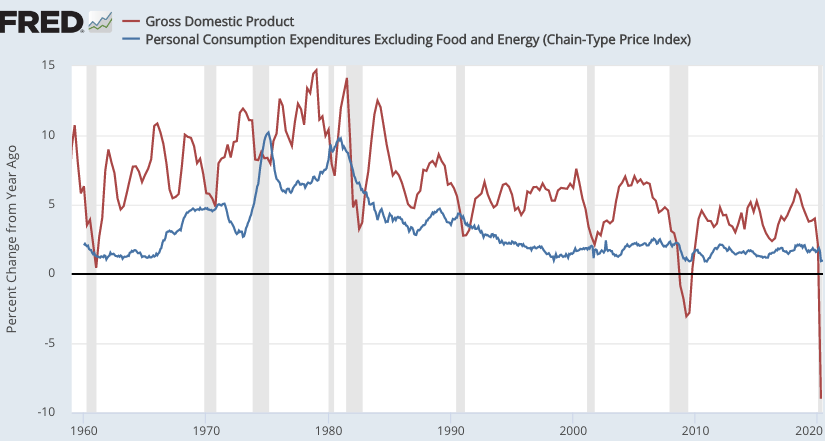

Just eyeballing the graph, it looks to me like core PCE inflation (blue line) typically starts falling about a year after NGDP growth (red line) begins to decline. (Focus on the NGDP slowdowns of 1979-80, 1990-91, 2000-01, and 2007-08.)

Think of core PCE as the part of the price level mostly made up of sticky prices, or alternatively those prices that are closely linked to wage costs. Thus wage costs do not determine oil or food prices in the short run, but do heavily influence the price of haircuts and restaurant meals.

[Note: There is a slight flaw in measured core inflation, as even the core includes some energy prices, which indirectly impact other production costs. Thus oil shocks slightly impact even core inflation, albeit much less than they impact headline inflation.]

When there is a tight money policy, both output and commodity prices immediately fall. Sticky goods prices (and wages) are not immediately affected.

A number of researchers have pointed out that monetary policy should try to stabilize the stickiest prices. That might be core inflation, or (as Greg Mankiw and Ricardo Reis argued) wage inflation. But that’s not easy to do, as sticky wages and prices respond slowly. It’s like trying to steer an ocean liner where the ship takes 15 minutes to respond after moving the steering wheel.

Thus you want to target the thing that is closely linked to future values of the sticky index that you are trying to target. That might be a futures contract linked to the core PCE, but it also might be current NGDP.

Of course even current NGDP is hard to control, which is why I’ve called for assistance from NGDP futures markets, notably my “guardrails” approach. But at least NGDP responds much more quickly than core inflation, and hence is a better target for avoiding short run instability. In mid-2008, there was an obvious NGDP problem, but no obvious core inflation problem. Keynesians rely on Phillips curve models to solve this problem, but NGDP is more reliable.

The (supposed) downside of targeting NGDP is that it allows a bit more variation in long run core inflation, even if it’s more stabilizing for the economy at cyclical frequencies. That “downside” is actually a feature not a bug, as George Selgin demonstrated in Less Than Zero. But even if it were a bug, it’s likely that the benefits of greater cyclical core inflation stability vastly exceed the downside of slightly bigger variations in the long run trend rate of core inflation, even if New Keynesian models are correct that PCE core inflation is the appropriate monetary policy target.

You want stable core inflation? Target per capita NGDP growth.

PS. This post does not apply to the Covid-19 economy. For that, you’d want to target NGDP at least 12 months forward, maybe 24 months.

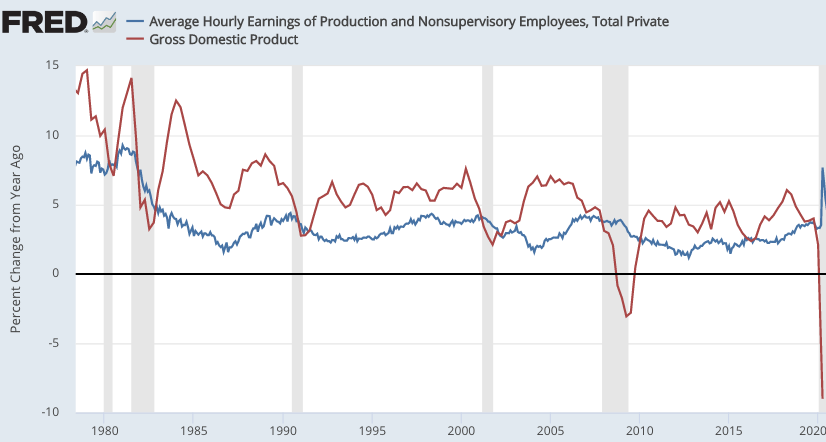

PPS. I could have written the same post, replacing core inflation with wage inflation (blue line). It also lags behind NGDP growth (red line):

Tags:

24. August 2020 at 10:14

How do government debt levels figure into NGDP target calculations? For example, if you were running the Fed would your NGDP target change as a result of the $5 trillion of debt we accumulated this year? And, if we do it again next year, would that affect your target?

24. August 2020 at 10:27

Carl, It depends on how the government responds to the debt. For any given monetary base, more debt usually means more NGDP. But the effect is modest at the zero bound.

24. August 2020 at 13:04

The old Sumner is back! Finally!

SSumner: “Here’s a conjecture. Core PCE futures targeting would look a lot like NGDP targeting” – it’s not a conjecture, it’s a tautology. PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditure Excluding Food and Energy” seems to be related to NGDP, which is broader. I.e., the set {A,B,C,D} tracks the set comprising the alphabet A through Z.

24. August 2020 at 15:49

I agree with most of these approaches, such as targeting NGDP LT or futures of some sort.

The argument is over which tools to use to obtain the target, and how high to set the target.

It is well to remember we operate in a world of globalized capital markets, and capital is a very fungible commodity.

But the US Federal Reserve is trying to obtain a target in a defined geographic market.

24. August 2020 at 17:46

Meanwhile, from CNBC:

“FEDERAL RESERVE

Powell set to deliver ‘profoundly consequential’ speech, changing how the Fed views inflation”

—30—

Profoundly consequential!

I am on the edge of my seat!

Exciting!

Actually, the Fed may allow PCE-core to run a little higher than 2% for a couple of years…maybe.

The RBAussie has had success with an inflation band target of 2% to 3%. If a central bank is to target inflation, I think the band makes more sense.

Still, it is (largely ineffective) lockdowns wrecking the US and global economies.

Pray for a vaccine.

And Trump is bad, bad, bad for pressuring the FDA to speed up the approval process for a C19 vaccine. Bad!

PS: Tyler Cowen has spent a lifetime bashing FDA clunkiness and slow approval processes.

In this particular matter, is Trump right? I think so.

24. August 2020 at 20:19

I’ve had thoughts in this direction myself at times. Why not target sticky prices other than wages, if you can target wages?

25. August 2020 at 10:50

Targeting the stickiest index was what Gunnar Myrdal argued for in Monetary Equilibrium—the boom for which he earned the Bank of Sweden prize. (It is to being cursed by such knowledge BTW that I attribute my failure to write more articles suitable for the NBER and QJE!)

25. August 2020 at 15:42

Add on. Suppose the US and the world become Japan?

Inflation, for whatever reason, dies.

Then…would not the best macroeconomic policies be those that drive unemployment lowest?

The deader inflation is, the more lively the argument for approaches to crush the scourge of unemployment.