Three strikes and you’re out

When I starting blogging, and started defending the EMH, I faced three anti-EMH arguments:

1. The obviously irrational housing price bubble.

2. The continual success of Warren Buffett.

3. The amazing returns earned by the hedge funds.

As you are about to see, all three critiques of the EMH have been recently discredited. Let’s start with the hedge funds. Here’s a recent article from the Economist, showing their early success was just a fluke:

Then there’s the amazing Mr. Buffett. Once again, the Economist comes to my defense:

Without leverage, however, Mr Buffett’s returns would have been unspectacular. The researchers estimate that Berkshire, on average, leveraged its capital by 60%, significantly boosting the company’s return. Better still, the firm has been able to borrow at a low cost; its debt was AAA-rated from 1989 to 2009.

Yet the underappreciated element of Berkshire’s leverage are its insurance and reinsurance operations, which provide more than a third of its funding. An insurance company takes in premiums upfront and pays out claims later on; it is, in effect, borrowing from its policyholders. This would be an expensive strategy if the company undercharged for the risks it was taking. But thanks to the profitability of its insurance operations, Berkshire’s borrowing costs from this source have averaged 2.2%, more than three percentage points below the average short-term financing cost of the American government over the same period.

A further advantage has been the stability of Berkshire’s funding. As many property developers have discovered in the past, relying on borrowed money to enhance returns can be fatal when lenders lose confidence. But the long-term nature of the insurance funding has protected Mr Buffett during periods (such as the late 1990s) when Berkshire shares have underperformed the market.

These two factors””the low-beta nature of the portfolio and leverage””pretty much explain all of Mr Buffett’s superior returns, the authors find.

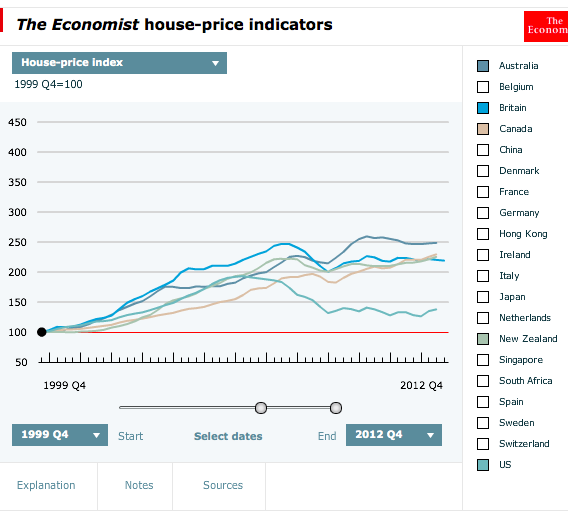

Then there’s the housing bubble. What goes up . . . stays up 4 times out of 5. That’s right, the housing bubble of 2005-06 was not something that would inevitably burst, as the anti-EMH proponents insist. Indeed if you look at the US, Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, it is the US that is the outlier. All saw big price gains during the boom years, but only the US bubble burst. The other 4 countries still have very high house prices:

Inevitably some commenters will insist that the EMH is not true. Yes, but no economic theory is precisely true. However it is and will always be a very useful model.

Asset prices are unforecastable; but here’s one thing that can be accurately forecast: One hundred years from now all the top finance departments will still be teaching this theory that almost everyone insists is “false.” And yet 99% of the “anomaly” studies published in econ/finance journals and constructed through tedious data mining will be long forgotten.

Tags:

7. February 2013 at 09:15

Scott,

The best argument against EMH is that it takes one month for the markets to incorporate monetary shocks, instead of one minute.

7. February 2013 at 09:21

I agree with the first two points.

However, there are still massive housing collapse risks in the UK, France, Canada, China (and maybe others?).

In the UK, the BoE is propping up housing lending through the Funding for Lending Scheme (even though it was aimed at SMEs originally), so prices resist. But they stopped increasing even in London now…

For Canada, see the FT article from yesterday:

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/47ee21dc-7045-11e2-ab31-00144feab49a.html

All over the world, house prices are naturally propped up by Basel regulations too (low capital requirements on direct lending and even less on securisation). Not sure this can last indefinitely.

7. February 2013 at 09:31

>All saw big price gains during the boom years, but only the US bubble burst.

Putting on my Bayesian hat, the US housing market “bubble” didn’t “burst”. The US housing market experienced cascading repricing from 2007-2009 based on the new information that the Fed was not committed to persistent NGDP growth. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand haven’t repriced because their central banks continue to signal such commitment. Now, the UK I’m not so sure about, but hiring Carney is a good way to resist dramatic repricing.

7. February 2013 at 09:32

I am a EMH believer, but please don’t use the HFRX to discredit hedge funds. On a dollar-weighted basis something like 90% of the industry does better than HFRX. It’s a index of daily valued, daily liquidity funds that have lots of transactional investor friction and other costs.

7. February 2013 at 09:40

I’m not sure how that article refutes the Buffett point. If anything, it identifies a market efficiency. For that article to be correct, we would need to believe

1) Warren Buffett was able to get capital at below market rates for 50 years.

2) Low beta stocks have been delivering above-market returns for 50 years.

This doesn’t say the market is efficient, what it says is that Buffett found and exploited a market inefficiency consistently for 50 years.

7. February 2013 at 10:12

Scott,

The persistent underperformance of hedge funds seen in your chart illustrates the problems with the EMH very well. One of the assumptions Fama likes to make is the ability to short. As it is almost impossible to short the overvalued hedge funds, the hedge fond bubble persists. If the EMH was true, rational investors would short hedge funds, driving down their valuations and increasing their future returns to the market levels.

7. February 2013 at 10:58

Jon,

“Low beta stocks have been delivering above-market returns for 50 years.”

The CAPM model flawed. CAPM is built from the EMH, but it has a incorrect assumption — that cash a combintation of cash and the market portfolio is optimal. There is no reason to think that optimal porflios should lie on the CAPM line. They should lie above the CAPM line. Low beta stocks should outperform.

7. February 2013 at 11:08

Just because house prices haven’t fallen in Australia, Canada, and the UK doesn’t mean they won’t fall. I think that house prices are generally tied to the growth in mortgage and credit growth hasn’t turned negative in Australia, Canada, and the UK yet; however, debt/income ratios haven’t really started to correct in those countries. I’d also like to add that I think house prices/median income and house prices/rent ratios are much better indicators than just the index. For example, if you get a massive influx of population, both house prices and rents increase, but price/rent ratios stay relatively constant.

I agree with the other comments on this post that house prices in Australia, Canada, and the UK do need to correct. Also, (bad) government policy has propped up house prices(like decreasing lending standards), but those policies are not sustainable and will make things worse later on. As for Canada, their debt/income ratios are still rising and it is not sustainable for debts to rise against incomes forever.

“If something is unsustainable, it will stop.”

7. February 2013 at 11:22

Also, my main argument against the EMH is that there are clear dependencies that exist in the data. One of the greatest mathematicians over the past 200 years did a lot of work on this(Benoit Mandelbrot); however, his work has largely been ignored. Just take a look at the Hurst exponent over any time period in a stock market; clear dependencies show up over certain time periods.

7. February 2013 at 11:23

Everyone, Beating back the anti-EMH arguments is always a bit of a “whack-a-mole” game. I don’t doubt that in shooting down three specific arguments, others can be pulled from the wreckage.

As far as the “you just wait, some day that asset price will go down” argument, it’s hard to think of any serious intellectual argument with less content. What does that mean? All markets go up and down. If the anti-EMH people can point to specific asset price moves and time frames that are useful to investors, that’s great—then we can all get rich. But if it’s just “someday I’ll be proved right,” then count me as being totally uninterested.

BTW, I was not suggesting hedge funds are a bad investment, just that they don’t violate the EMH.

7. February 2013 at 11:25

Scott — I agree with you that Warren Buffett doesn’t say anything about the EMH, from a number of different perspectives. But I always thought that particular research piece was shockingly inadequate, and it’s inadequate in a way that is actually a good rebuttal to EMH critics: Warren Buffett is not just some stock picker.

One problem for some EMH supporters is they feel the need to rebut the existence of all kinds of different examples, like hedge funds, private equity and, most of all, Buffett. But what this forgets is that these things are all playing a very different game, Buffett in particular.

Not only does he have the “cheap leverage” of his insurance float, but, by and large, he’s a control investor, meaning he buys entire companies — after getting the benefit of due diligence after signing various confidentiality agreements, which, among other things, lock you up for buying market shares other than in connection with an announced deal (it’d likely be illegal for insider trading reasons anyway). All of that is well outside of anything EMH has to speak about.

He also famously gets securities that are not public securities, because his investments are themselves powerful market information (something you sadly cannot say about my investments). Bank of America and Goldman Sachs offer him preferred stock that not only give him equity rights but also have 10%+ dividends because if he invests it will help stabilize their market price. Again, that is just not EMH territory.

I don’t want to belabor the point, and he does often buy ordinary publicly trades shares, typically because the company he likes, like Coca-Cola, is large so buying the entire thing is infeasible and in any event if you buy on the market you don’t have to pay a control premium. But that research report about Buffett’s advantage always seemed to me to miss the forest for the trees. What the EMH has to say about the markets has no direct applicability to what Warren Buffett does; it’s a point academics miss when they tell Buffett he’s just “lucky,” like the “greatest” coin flipper of all time, and he misses it when he responds to them about his inherent skill. He’s simply playing a different — maybe better, maybe not given the uncertainty, risk and cost — than we are. To me the EMH is about public information for passive investing, primarily in public equity markets. (Most EMH proponents don’t claim that *all* markets are efficient, like the market for tranche B loan debt, etc, though they may say they tend towards efficiency.)

7. February 2013 at 11:28

I will also add one caveat to this. Some claim that the EMH implies a random walk, others claim that it has nothing to do with a random walk. Wikipedia says that even the weak-form implies a random walk, but that can be disputed. Either way, prices are not a random walk; there are clear trend structures in the data.

Also, I was talking to one of my old professors a while ago; he used to be a trader for around 15 years and wrote his own algorithms to trade. This was the quote:

“Trade for a month and then tell me markets are efficient.”

That being said, I’m sure there are several traders (or former traders) on this blog that would certainly disagree with that statement and could very well be right about that.

7. February 2013 at 11:32

Scott,

I have been seeing a lot on “Currency Wars” as of late and feel you need to provide some true insight ans analyses to the situation. Fits better with Japan post but…

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/patterson-feds-global-unintended-consequence-181426342.html

Joe

7. February 2013 at 11:34

Scott:

“I was not suggesting hedge funds are a bad investment, just that they don’t violate the EMH.”

No. One way or another, hedge funds violate EMH.

If they are able outperform the market, this violates EMH.

If they are not, their enormous fees are unjustified, yet the value of hedge fund units does not reflect this, violating the EMH.

The problem is that arbitrageurs who short hedge funds while investing in market portfolio do not exist. Their existence is necessary for the EMH to be true.

7. February 2013 at 11:36

In other words, prices paid for hedge fund units are irrational, yet there is no market process that corrects this.

7. February 2013 at 11:58

(quick EMH summary http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Efficient-market_hypothesis )

I never worried much about this because it’s an “outrun the bear” issue — just as I only have to outrun you, not the bear, to avoid being eaten by the bear, markets only have to be more efficient than the government, because those are the two options. And that’s a bar about as low as outrunning a guy who can barely lift himself out of bed.

7. February 2013 at 12:05

123 — you could do a synthetic short. It would have some informational issues, but it’s not impossible. Or you could just short a company that invests heavily in HF, say, AMG.

7. February 2013 at 12:15

Suvy,

The efficient markets need not follow a random walk. You can fix the wiki page if you want. Here is a classic site:

Fama 1988

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/1833108

“But the predictability of long-horizon returns can also result from time-varying equilibrium expected returns generated by random pricing in an efficient market.” I think there is also a discussion in Fama 1970 about Random Walk vs. Efficient markets

7. February 2013 at 12:29

Here’s how I think of it.

The EMH is like consumer theory. No real world consumer is as rational as the model suggests, but that doesn’t mean the income and substitution effects aren’t true. That’s the essense of consumer theory.

Obviously the EMH isn’t 100% true, but that still doesn’t refute the essense of the model; that stock prices reflect public information, that stock prices are determined by future expected cash flows and that you can’t predict future prices.

If you buy shares because you believe that they are undervalued, you’re really just taking a punt.

7. February 2013 at 12:43

@TallDave

How do you short HFs synthetically? It’s a pity Intrade does not have the Buffett – Seides bet listed.

AMG does not work, as AMG is long HF fees, but we want to short net HF returns.

7. February 2013 at 12:44

@TallDave

Do HF index futures exist?

7. February 2013 at 13:03

For the most part, I agree with EMH in that markets are pretty quick in pricing information, and in a big-picture viewpoint it makes sense. However, from smaller scale perspectives EMH has some problems. For example, according to EMH, markets are efficient because there are so many smart traders out there, but if there are so many smart traders and they know that they can’t make profits by trading why is there so much trading going on? How is the level of trading going on rational and efficient? Isn’t the logical conclusion of EMH that nobody would trade anymore?

In the end I have a lot respect for EMH, but at the same time I know that even though the market may be efficient, it still may be wrong, which gives me the incentive to trade and try to make some money. It’s just a matter of gauging market sentiment, after all there are so many different ways the same set of data or information can be interpreted. If you have the same interpretation as the crowd, the markets are efficient so you won’t be able to make a profit, but if you’re interpretation is different and you’re right then you can make a profit.

7. February 2013 at 13:05

123

There are no HF index futures. You could probably get Goldman Sachs to write a total return swap for you, but if you don’t have a few million to put behind the idea, they probably don’t want to talk to you.

“I was not suggesting hedge funds are a bad investment, just that they don’t violate the EMH.”

No. One way or another, hedge funds violate EMH.

EMH suggests that it is hard to beat the market, but it is pretty easy to design a portfolio that is poorly diversified and will underperform likely the market for a given level or risk.

Regarding hedge fund fees, it is hard to beat the market before fees. So, some EMH advocates will argue that you should never pay invetment management fees.

7. February 2013 at 15:46

Martin Wolf quotes Goodhart

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/ae8b292a-6fc4-11e2-8785-00144feab49a.html#axzz2K9wZ4e2m

Altering the longer-term regime would rightly take time. This is most obvious if one considers a popular alternative: a shift to targeting nominal gross domestic product. Yet, as

Charles Goodhart of the London School of Economics and co-authors note in a recent paper, this attractive idea has drawbacks: the target is far less transparent than prices; the data are not only published quarterly, but are constantly revised; the impact on expectations might even be highly destabilising; and it would be extremely difficult to fix on a target for the growth or level of nominal GDP, given the uncertainties about potential real growth and the fact that nominal GDP is now 13 per cent below the pre-crisis trend. The difficulty of agreeing quickly on any alternatives might rule the notion out for immediate needs.

7. February 2013 at 17:27

[…] full story on themoneyillusion.com var featureBoxVar = […]

7. February 2013 at 18:25

Dr. Sumner:

Spaking of whack-a-mole, these three “anti-EMH” arguments are not exactly good anti-EMH arguments. They’re nowhere near the crucial anti-EMH argument that really exposes EMH as flawed.

I’m not just saying this because these three examples have been seriously challenged by recent events. You just so happened to have mentioned them, and none of them are even near my radar, so I am piping up, so to speak.

My biggest criticism of the EMH is twofold.

One, it is often presented as an empirical, a posteriori theory, it is in actuality an a priori, non-falsifiable theory that cannot be empirically falsified no matter occurs.

Two, it is self-refuting.

1. Non-falsifiable?

Suppose the following events occur in two separate worlds:

World A, time 0 to time T: Hedge funds make billions for a number of years. Warren Buffet is beating the market year after year. Investors make a killing in a housing boom.

World B, time 0 to time T: Hedge funds lose billions. Warren Buffet loses his shirt. Investors of MBSs jump out of skyscrapers.

An EMH argument to explain world A would be like the following: “See? EMH theory can be applied to this world no problem: You can’t beat these sophisticated investors. They are pricing in everything relevant there is to be known in stocks, options and other securities.”

An EMH argument to explain world B would be like the following: “See? EMH theory can be applied to this world no problem: Not even the best investors can persistently beat the market.”

EMH can’t be wrong. If a Warrent Buffet beats the market for 5 years, then EMH isn’t wrong. If he beats it for 10 years, then EMH isn’t wrong. If he beats it for 20 years, then EMH isn’t wrong. Why isn’t EMH wrong? Because if we wait long enough, Warren Buffet will lose.

2. Internally consistent?

EMH proponents often use the tactic of rhetorical questioning to explain their insistence EMH is true: “Oh yeah? Well if EMH is false, then show me a scientific model that tells me how to persistently beat the market! Just admit it that you can’t. Not even the most sophisticated investors can do it.”

This form of rhetoric exposes a fundamental self-contradiction of EMH. For the EMH claim being advanced can be paraphrased as this:

“If EMH is false, then there must be a scientific model that can be used to persistently beat the market. The only valid alternatives are A. Scientific model and B. Ignorance. There is no other valid knowledge of the market.”

The self-contradiction of this claim can be seen by simply considering the fact that it is itself a non-scientific claim. One cannot logically advance the claim that the only valid forms of knowing the market are scientific model or ignorance, and then believe one is saying something true about the market. Only scientific models are valid, and merely saying “Only model or ignorance” is not itself a scientific model!

Imagine someone saying “If you cannot show me a scientific model that can persistently produce artworks on par with Rembrandt’s, then you must admit that producing such artworks are pure luck.”

It’s pretty obvious that this is a bunch of nonsense, but this is precisely what proponents of EMH are rhetorically claiming justifies EMH!

It’s pretty clear why there is no model that can beat the market in the long run: If a model seems to be able to beat the market, then more and more people will come to use the model, and eventually the model will become the market itself. To say then that no model can persistently beat the market in the long run, is really just saying the market can’t beat itself. Well yeah, but how is that a useful or penetrating insight of markets?

There is a way for a person to beat the market, other than just luck…in theory: To have an understanding of unique past events that exceeds other’s understanding. This cannot be done by a model of course, because models abstract away from unique past events, and invariably ends up seeking to link common occurrences in a diverse set of events, and as soon as this is done, the unique past is no longer even being truly considered. You can’t scientifically model Rembrandt, or Warren Buffet.

Rembrandt knew how to paint better than others. He knew that this stroke of such and such paint should occur after such and such previous stroke of paint. This cannot be modeled because models only look at generalities, and Rembrandt was certainly no general performer. Nobody is to be precise.

The fact that Rembrandt sometimes had good judgments, and sometimes bad judgments, and the fact that Buffet sometimes had good judgments and sometimes bad judgments, does not imply that what they do is pure luck. The fact that they can’t be modeled is not proof they are lucky. It’s just proof that a model approach is inadequate to explain their behaviors. To conclude it’s all luck is just a product, an outcome of the a priori (and contradictory) theory that the only “scientific model” knowledge is real knowledge.

EMH is an unfortunate side-effect of a prevalence of “scientism” that has infested economics.

In short, not everything that can be known has to be modeled scientifically.

7. February 2013 at 18:56

“An EMH argument to explain world A would be like the following: “See? EMH theory can be applied to this world no problem: You can’t beat these sophisticated investors. They are pricing in everything relevant there is to be known in stocks, options and other securities.””

This argument is not consistent with EMH. There is a sense in which the EMH isn’t testable. To test it requires the correct model for risk. Thus, if hedge funds gained high returns for an extended period, an EMH advocate would they are being compensating for holding more risk. Essentially, the argument used for leverage and Buffett This has been known at least sense Fama 1970 and is called the Joint Hypothesis problem.

7. February 2013 at 19:03

Charlie:

“This argument is not consistent with EMH.”

Why not?

“To test it requires the correct model for risk. Thus, if hedge funds gained high returns for an extended period, an EMH advocate would they are being compensating for holding more risk.”

Except you can’t infer a particular risk from a given historical return. A high historical return does not necessarily imply high risk. A high expected risk could imply a higher expected return.

“This has been known at least sense Fama 1970 and is called the Joint Hypothesis problem.”

Not really related to this post, but sure.

7. February 2013 at 20:05

123,

There are a few ways, but basically you’re trying to be short where they’re long. IIRC Barclay’s has a couple hedge fund shorting indices.

Shorting AMG is a direct bet on EMH. If you think EMH is wrong, you should go long AMG.

7. February 2013 at 20:11

Geoff,

If had a million investors with $1 all betting everything on a coin toss every minute until they ran out of money, eventually I would have a millionaire who had never lost a coin toss. That wouldn’t necessarily mean he was any good at predicting coin tosses.

If I gave a million people paintbrushes and canvas and one of them turns in a Rembrandt, it’s probably not an accident.

Buffett lies somewhere between.

7. February 2013 at 20:28

Those are *not* the arguments against the EMH I saw in the comments section of this blog, nor are these the arguments I made against the EMH in the comments section of this blog.

7. February 2013 at 20:32

Scott, you’ve never addressed the points and arguments I’ve made regarding the EMH — including the fact the Fama doesn’t believe the EMH implies or supports the claims you pretend it to support.

7. February 2013 at 20:59

Tall Dave,

There are a bunch of monkeys at my door. They want to discuss the script of Hamlet.

7. February 2013 at 21:15

My understanding of emh comes from the Random Walk Down Wall Street in which is claim is that over the long run betting on the market as a whole will do better over that period than a high priced manager directed fund. Fair enough you can grow rich slowly.

However are houses always a good investment? No. The book “Safe as Houses?” Looks at several countries and the answe is “no” housing is not a safe or even a lucrative investment. Especially if you invest in any housing market over time. This refutes emh in this area of investing and my experience shows that a savvy investor who doesn’t use a emh like style to invest can beat the market. In fact I rather choose a smart local housing investor than somebody who bets my housing investment will go up with the market, because it might not.

7. February 2013 at 21:16

Pardon any errors I wrote that on my phone.

7. February 2013 at 21:53

Excellent blogging.

In the main, and certainly as a indicator of what macroeconomic policy should be, EMH works.

Also, on Buffett: He also buys whole operating companies, such a Diary Queen and Benjamin Moore paints. It may be he is a great negotiator on acquiring assets.

7. February 2013 at 21:59

It’s like baseball. For the most part, you’re not going to go out and find a bunch of hidden talent for your team. On the other hand, there can be a Jackie Robinson moment, where the world is so universally biased, that if you take advantage of the bias at the right time, you’ll very likely succeed.

There are so many financial securities and there are so many reputational risks, agency problems, and moral baggage with finance, that Jackie Robinsons are always available. But they are fleeting, and the timing has to be right. And, meantime, every bar has twenty guys lined up every night that know they could run the team better. Those guys don’t disprove EMH, and the existence of Jackie Robinson doesn’t mean that those guys could actually run the team like they think they could. EMH is basically right.

I’m surprised that you don’t give some weight to the idea that the world is so biased about what the Fed does that it leaves small, temporary, and predictable gains on the table. Here we are on the 3rd QE episode where long rates are rising, and every academic, trader, and Fed governor I hear from tells me that the Fed is holding rates down by buying treasuries. And each episode has taken at least a couple of months for rates to top out.

8. February 2013 at 00:03

Regarding Buffett, the Economist, while correct as far as it goes, gets only part of the story. Buffet’s brilliant idea of packaging an investment fund inside insurance operations not only gave him access to cheap capital, it allowed him to game the tax system. Insurance companies are allowed to set aside reserves against future expected claims and these reserves are not subject to current tax. Keeping ahead of the tax man simply required an ever- growing insurance operation (and ever-increasing premium reserves). Buffett has probably gamed the US tax system to his advantage more than any person in American history. While he favors raising capital gains tax rates and marginal income tax rates on individuals, nothing he ever proposed would affect his own tax liability or his ability to further accumulate wealth.

As far as Buffett’s stock picking expertise is concerned, his bet against the hedge fund actually demonstrates that Buffett himself believes in the EMT. He knows why he’s been successful and its not because he’s a great stock picker, although he’s been good enough to avoid major missteps. It would be interesting to go back and recalculate Buffett’s return on his stock investments (without the leverage) and compare that to the return, say, on the S&P 500. I think his record would look pretty average. Buffett has had one big advantage though in recent decades—his size. He’s able to go to companies and demand terms in privately negotiated deals that normal investors can’t. But, that does not have anything to do with the EMT.

8. February 2013 at 00:06

When I refer to the EMT, it’s the same thing as the EMH.

8. February 2013 at 00:20

mMrkets are unpredictable, and therefore difficult to outperform consistently. Let’s move on.

8. February 2013 at 01:36

Professor Sumner, you should read the study referenced by the Economist before using it as a defense of EMH. The authors created an idealized portfolio with monthly re-weightings, no transaction fees, no liquidity spreads, and no taxes, which they then compared to an idealized portolio drawn from Berkshire Hathaway 13-Fs on a pre-tax basis. I don’t believe that the authors intended for the paper to be used to support EMH, or they would have created less fantastical tracking portfolios. There is also, I believe, an error in conflating a pre-tax basis comparison with an ex-tax comparison. Tax efficiency considerations influence investment decisions ex ante.

There is also a more fundamental flaw with your argument. If, after the fact, I can describe the technique that allows you outperform the market, then I have not suddenly “proven” EMH. Let’s agree with your implied proposition that the market has been waiting for these researchers to come along to crack the code (against their own intentions, no less). Well, the test is yet to come. Certainly, the market will not allow Buffett to reap such outrages gains now that the study has been released!

8. February 2013 at 01:41

Vivian Darkbloom, Buffett’s bet against the hedgies is more of an “It can be done, but only I can do it” attitude. Size is an advantage in many respects, but generally not so far compounding rates are concerned. If my goal were simply to compound at high rates, I would much rather start with a seven figure AUM in a discount brokerage, than swing my eleven figures at convertible securities with 10% coupons. He only gets those deals when far more asymmetric opportunities are available to more nimble portfolios.

8. February 2013 at 02:07

Greg and Geoff raised solid points. There is a pointlessness to taking a market participant and overweighting its importance against an argument that applies to the market. If your version of EMH requires that not a single individual’s decision making process will lead to greater probabilities of success versus the overall market probability pathways… Well, good luck. Only the most masochistic statistical geek would pursue such an argument, although it would be a great service to humanity if you discover such a method of analysis.

8. February 2013 at 02:07

Greg and Geoff raised solid points. There is a pointlessness to taking a market participant and overweighting its importance against an argument that applies to the market. On the other hand, if your version of EMH requires that not a single individual’s decision making process will lead to greater probabilities of success versus the overall market probability pathways… Well, good luck. Only the most masochistic statistical geek would pursue such an argument, although it would be a great service to humanity if you discover such a method of analysis.

8. February 2013 at 02:08

The easiest way to see the flaw. In the emg is to note the perennial over reactions of the market to bad news. Check out the BP share price following the macondo oil spill. If a share is worth the present value of future cash flow, then the stock market was giving an average scenario where it cost BP half of all future profits to clean up. That simply wasn’t plausible for a company the size of BP. Even if it was banned from us waters and had to sell all its us assets and pay a massive fine it still would not have been that bad. Other companies like Catlin tell a similar story, it is a reinsurer exposed to many of the 2012 natural disasters. It had a bad year, but natural disasters are stochastic and there is no reason at all to believe that it’s future risks are at all different from other insurers, yet it is priced at a massive discount to the other large reinsurance companies in the UK.

Moreover there exist plenty of anomalies in markets. Distressed. Debt is often underpriced. Low beta stocks have outperformed forever. Small caps outperformed for ages. Momentum has persisted for decades, volatility capture strategies have been profitable for more than a decade.

The market is a living thing, usually when an anomaly becomes widely known it disappears, because as lots of money follows a strategy I smooths out the inefficiency. However, some inefficiencies appear to be features of rigidities. Institutional investors have short time horizons to measure performance, and so the seldom follow the value strategies that require patience over multiple years. They are also likely to cut their losses when they hav a. Disaster, rather Han keep a loser on their books for years while its price normalises. All of this ups volatility beyond the efficient frontier and creates opportunities on multi year horizons. Similarly illiquid investments often offer a large premium to people with long time horizons.

Also, remember that even if you are a die hard emh supporter, the goal of market participants differ. Maximising returns is not the same as maximising risk adjusted returns which is not the same as managing career risk for portfolio managers. A market can only be efficient if all participants have the same goals, as soon as you have large players who are not maximising returns you are creating inefficiencies.

Finally, look how much more efficient markets have become even since 1960. Nearly every arbitrage or anomaly based strategy was immensely profitable in 1960, most of them have faded away as they became well known. Are you seriously telling me that there is no scope for further improvement? That financial players have reached the absolute pinnacle of financial understanding such that there are no inefficiencies left? I think not!

8. February 2013 at 02:39

I am with Yglesias on this one. That is: I am not sure what efficiency has got to do with anything that we are seeing here.

As far as I can tell (and I can never be sure on this one), EMH makes (1) a theoretical and untestable claim that the markets reflect all currently available (public?) information and (2) an empirical and testable claim that no one individual can beat the market over an extended period of time.

Now, I think arguing over (2) is a bit of a waste of time. One the micro-investor level, it’s clear that there are anomalies (Buffett, etc.), but it’s also clear that those anomalies are easily explainable within the constraints of a statistical distribution that you should expect. On a macro level, while there seem to be bubbles, it’s indeed easy to advance a bayesian argument that there is just repricing going on in light of newly available information.

The key problem with EMH is this: (1) is only one of at least two possible theories that fits the empirical result in (2). The result of (2), even if true, could happen EITHER becuase the collective wisdom of the market always beats the wisdom of any single investor OR because the collective markets are more like a chaotic system that is quite simply unpredictable. To me, the latter is just much more simple, but people can pick their poison. Unpredictability of the future, however, is just not very sexy – as it has absolutely nothing to teach us.

8. February 2013 at 06:28

Joe, Let’s have some currency wars. Please!

123, I think you misunderstand the EMH, it does not say the risk adjusted rates of return should be the same ex post. It says the risk adjusted expected rates of return should be the same ex ante.

Tim and Kenan, I agree.

Geoff, Of course the EMH could be falsified–suppose the return on mutual funds was reliably better or worse than average.

Greg Ransom, I agree with Fama on the EMH.

Vivian, I agree that there is some regulatory/tax gaming going on here.

Al, I agree that paper was not used to bash the EMH, but I’m using it for that purpose.

Phil, I’ve discussed anomalies many times. The EMH predicts that there will be billions of anomalies that are statistically signficant at the 95% level. It’s just our finance professors who don’t know that.

Alekseyev, I don’t really agree with Matt. Markets efficiently aggregate information. The term “efficiency” does not mean “never makes mistakes.” Soviet central planners do not efficiently aggregate information.

8. February 2013 at 06:46

Scott, of course I’m interested in ex-ante expected risk adjusted returns only:

EMH says market returns should be equal to returns on assets hedge funds hold. It also says market returns should be equal to returns hedge fund investors receive.

But it is matemathically impossible, as hedge fund fees are huge and very different from zero.

8. February 2013 at 07:39

Scott, you make claims for the EMH which Fama publicly rejects.

Scott writes,

“Greg Ransom, I agree with Fama on the EMH.”

8. February 2013 at 07:50

Scott, let me add a fourth anti-EMH argument to your list.

It’s actually your own argument: Wallace neutrality does not hold.

If Wallace neutrality doesn’t hold, then trades that offer risk-free profits are being left on the table and markets are not efficient. I wrote about this in an older post.

In any case, a reasonable middle ground is that we shouldn’t have discussions about EMH or not-EMH. Rather, the real world is somewhere on a range that approaches EMH. We can have arguments about how close it gets, but insofar as you state that Wallace neutrality doesn’t hold, you must admit that you are somewhat removed from the extreme pole of EMH… but perhaps not so removed as a hedge fund manager who is sure he can do 20% better than the market.

8. February 2013 at 09:37

Tall Dave:

“If had a million investors with $1 all betting everything on a coin toss every minute until they ran out of money, eventually I would have a millionaire who had never lost a coin toss. That wouldn’t necessarily mean he was any good at predicting coin tosses.”

“If I gave a million people paintbrushes and canvas and one of them turns in a Rembrandt, it’s probably not an accident.”

“Buffett lies somewhere between”

Al:

“There is a pointlessness to taking a market participant and overweighting its importance against an argument that applies to the market. If your version of EMH requires that not a single individual’s decision making process will lead to greater probabilities of success versus the overall market probability pathways… Well, good luck. Only the most masochistic statistical geek would pursue such an argument, although it would be a great service to humanity if you discover such a method of analysis.”

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, Of course the EMH could be falsified-suppose the return on mutual funds was reliably better or worse than average.”

EMH refers to people’s knowledge and investment ability, not the performance of a specific class of securities (e.g. mutual funds) relative to another, more wider class of securities (e.g. index).

And even if I did show that mutual funds, for the last X years say, underperformed or outperformed the average, then EMH will just explain that away as a fluke, because we can always wait until it incurs losses in year X + 1. We would be told “Of COURSE there will periods of time where things like this happen! EMH “predicts” that there will be such anomalies.”

8. February 2013 at 09:43

Sorry Tall Dave and Al, I quoted you ready to reply, but forgot…

Tall Dave:

Only if your a priori theory is that returns are earned by luck in the market, do you conclude that the returns you observe in the market are the product of luck.

You are recognizing talent in the art example because your a priori theory is that it is not luck that allows a person to paint on par with Rembrandt.

Al:

“There is a pointlessness to taking a market participant and overweighting its importance against an argument that applies to the market. If your version of EMH requires that not a single individual’s decision making process will lead to greater probabilities of success versus the overall market probability pathways… Well, good luck. Only the most masochistic statistical geek would pursue such an argument, although it would be a great service to humanity if you discover such a method of analysis.”

Even if someone did outperform the average, EMH would claim to be not wrong, because if we just wait some more, they’ll eventually lose, just like they do in Vegas right?

8. February 2013 at 12:55

[…] would not endorse a strong interpretation of Friedman’s essay, I often come across the defence ’it’s just an abstraction, all models are wrong’ if I question, say, perfect […]

8. February 2013 at 13:14

Some more fun with bubble arguments. Harder to predict ex ante.

http://www.badoutcomes.blogspot.com/2013/02/the-housing-bubble-that-wasnt.html?m=1

Tip of my hat to you.

8. February 2013 at 13:27

In other words: EMH says hedge fund manager should be indifferent between his current portfolio and a market portfolio. EMH also says the hedge fund investor should be indifferent between his investment in hedge fund and a market portfolio. But both can’t be true, as hedge fund fees are huge.

8. February 2013 at 14:13

This is a silly discussion. Basic economics tells us that markets cannot be efficient. That stuff goes back to stiglitz’s papers ( god bless his economist’s soul) in the 80’s. After all, if you maintain that active management is simply a waste of resources, you need to explain a gigantic bout of irrationality that has been going on for decades. You also have to explain how markets are supposed to aggregate information by passive investment. If nobody collected information, where would the market get the information from?

Cochrane has recently written about that issue quite convincingly in his response about the size of the finance industry. To follow his example, it’s not the ex post performance of the hedge funds that tell you anything about efficiency, it’s the fees.

8. February 2013 at 19:18

Greg, You’ll have to be more specific.

JP, You’ll have to explain how Wallace neutrality applies to the EMH. I thought it had something to do with whether cash and zero rate T-bonds are perfect substitutes.

123, The EMH say markets are efficient, not that hedge fund buyers are smart. The EMH says indexed funds are a better buy than managed funds, not that managed funds can’t exist.

Krzys, The EMH is false . . . long live the EMH.

I’ll stop believing in the EMH when the top schools stop teaching it.

8. February 2013 at 19:25

Thanks Charlie, That’s a good one. And how about Shiller’s stock market model? Weren’t stocks over-priced when the S&P got above 900? If not, why didn’t Shiller put out a buy signal when the S&P was 750?

8. February 2013 at 20:17

Geoff,

Yes, math is usually a priori reasoning, but we generally accept math as true anyway. Moving and counting beads is a lot of work, especially when you have exponents.

Unlike painting, statistically some people are going to be lucky investing irrespective of skill. That doesn’t happen in painting, we can know this a posterior by observing the distribution of art.

It looks like Buffett’s returns were nothing special, after considering leverage and low beta. He wasn’t lucky or skilled at investing, except in the sense of utilizing leverage and low beta.

8. February 2013 at 20:18

Sorry, bad tag!

Geoff,

Yes, math is usually a priori reasoning, but we generally accept math as true anyway. Moving and counting beads is a lot of work, especially when you have exponents.

Unlike painting, statistically some people are going to be lucky investing irrespective of skill. That doesn’t happen in painting, we can know this a posterior by observing the distribution of art.

It looks like Buffett’s returns were nothing special, after considering leverage and low beta. He wasn’t lucky or skilled at investing, except in the sense of utilizing leverage and low beta.

8. February 2013 at 20:30

123,

That would mean EMH requires hedge fund investors to be efficient. They only manage about $2T in assets, global financial assets seem to be around $200T. They probably represent < .1% of the population. That would be a very strong version of EMH!

8. February 2013 at 21:50

Scott,

EMH is not false, it’s only circular. You either take your basic principles of economics seriously or you don’t. An efficient market is a contradiction in (economic/neo-classical) terms. In other words, it is a useful limiting concept, but no market can be fully efficient, there have to be incentives for information gathering/trading, or you have to postulate irrationality on a …uhh…macroeconomic scale.

You cannot have the same people your model makes responsible for properly reacting to monetary signals of the fed, be, at the same time, engaged in the most wasteful activity ever.

9. February 2013 at 07:37

Scott: ” The EMH say markets are efficient, not that hedge fund buyers are smart.”

Typical hedge fund investor is smarter than a typical stock investor, but it does not matter at all. I am comparing one market for financial assets (stocks) to another financial market (hedge fund units).

I believe that NYSE is more efficient than market for hedge funds, and the market for hedge fund investments is more efficient than say Ukrainian stock exchange.

9. February 2013 at 07:41

“You’ll have to explain how Wallace neutrality applies to the EMH. I thought it had something to do with whether cash and zero rate T-bonds are perfect substitutes.”

From my understanding it just means that whenever reserves are in excess (and no longer have scarcity value), OMOs can’t raise asset prices. All assets have a fundamental value based on the discounted value of their future cash flows. OMOs can’t push price above fundamental value because profit-seeking traders will jump on the opportunity to sell all their holdings at any price marginally above fundamental value. The central bank ends up holding every asset in the economy.

If a central bank manages to push up asset prices with OMOs and does so having only bought up, say, 10% of the assets in an economy, then there’s some sort of market inefficiency. For some reason, traders didn’t sell the central bank all their assets. So you’re something less than a pure EMHer.

9. February 2013 at 11:23

Krzys, One could say the same about S&D; it’s an approximation of reality as no individual firm could have no impact on price, unless market quantity was infinite. Same argument.

123, See my previous response to Krzys. In my view the EMH does not say all markets are efficient, it says the US stock and bond markets are efficient. Other markets (Hedge funds, Ukraine, rare coins and stamps, etc) may be somewhat efficient, depending on how closely they approximate the US stock and bond markets. It’s a matter of degree.

JP, I don’t think you need to assume market inefficiency, just that cash and T-bills are not perfect substitutes, even if they have identical expected rates of return. They differ in other dimensions not picked up in the typical finance models (liquidity, risk of being stolen, etc.)

9. February 2013 at 14:25

Scott

Here’s another way of putting it; saying that anti-EMH theories are useful is like saying its useful when the weatherman tells you there was a hurricane yesterday.

9. February 2013 at 14:54

Scott: “In my view the EMH does not say all markets are efficient, it says the US stock and bond markets are efficient. Other markets (Hedge funds, Ukraine, rare coins and stamps, etc) may be somewhat efficient, depending on how closely they approximate the US stock and bond markets. It’s a matter of degree.”

But then it is possible to imagine a market that is even more efficient than US stock market.

I agree that US treasury market is quite efficient, but other US bond markets can be very inefficient. Even in the treasury bond market the inefficiencies were visible with the naked eye at the end of 2008 (at that time treasuries with very similar maturities had very different yields).

And finally, if you say Ukrainian stock market is not efficient, it makes sense to dynamically manage your exposure to the Ukrainian stocks.

9. February 2013 at 16:15

“JP, I don’t think you need to assume market inefficiency, just that cash and T-bills are not perfect substitutes, even if they have identical expected rates of return. They differ in other dimensions not picked up in the typical finance models (liquidity, risk of being stolen, etc.)”

Scott, I don’t think it’s about substitutability. Consider OMOs in equities. Stocks are less liquid than reserves, more risky, and often pay no dividend. The point of Wallace neutrality is that OMOs can’t move equity prices above their intrinsic value. If the Fed tries to push stock prices up, traders will immediately sell every equity they own to the Fed. If traders don’t, then markets are inefficient.

9. February 2013 at 17:37

What about this that I read somewhere?

“One of the more interesting anecdotes I picked up last week was from a businessman who said that after his firm issued the first paychecks of the year, virtually every employee came to the payroll office and asked why their paychecks were lower, evidently unaware that the payroll tax cut had expired.”

9. February 2013 at 17:40

What about the housing bubbles in Spain and Ireland?

9. February 2013 at 18:33

I think the interesting question about WN is whether it applies to financial assets versus real assets. (IMHO it a pretty close approximation if you’re comparing one financial asset against another financial asset).

9. February 2013 at 19:14

Talldave, you misread the study. You might be confusing a “Bet-Against-Beta” adjustment with a beta adjustment, while also ignoring the other factor adjustments. For example, the researchers reported a “Buffett” Sharpe of 0.76 compared to the “market” Sharpe of 0.39. And like Professor Sumner, you are also ignoring some idealized methods of constructing the portfolios that make the study inappropriate for saying one thing or another about EMH.

Professor Sumner, Frazzini and his partners believed that they have found an algorithm to explain Buffett’s outperformance relative to the market, even adjusted for leverage. Normally, to test for EMH, wouldn’t you then watch for Buffett’s idealized portfolio to match market returns going forward? You haven’t explained the logic of using an explanation for leverage adjusted outperformance as evidence against such outperformance.

10. February 2013 at 13:36

Tim, I’ve found the EMH very useful in my academic research on the Great Depression. I’ve found the theory very useful in my personal investments (index funds). The theory is useful to policymakers–lets them know they can’t predict housing bubbles any better than banks.

123, You said;

“But then it is possible to imagine a market that is even more efficient than US stock market.”

Yes, clearly.

JP, That sounds rather unlikely doesn’t it? So Wallace claims the central bank of Iceland could buy the entire world stock of equities, without creating inflation in Iceland? I’m not trying to be sarcastic here—I honestly don’t understand the claim being made.

Fed up. Of course people were surprised! Didn’t all of the media tell them that Obama was only raising taxes on the rich?

Fed up, And what about all the other European and Asian countries that saw big price run-ups, but no crash?

Al, I was responded to the claim that Buffett was skilled at spoting individual companies that were likely to do very well. In fact, his advantage came from leverage. Now there might be an inefficiency associated with leverage and value stocks, but that’s an entirely different argument. It’s also one much more susceptable to the counterargument that he got lucky.

10. February 2013 at 16:25

Scott

Yes, that was my point.

10. February 2013 at 17:52

“That sounds rather unlikely doesn’t it? So Wallace claims the central bank of Iceland could buy the entire world stock of equities, without creating inflation in Iceland? I’m not trying to be sarcastic here””I honestly don’t understand the claim being made.”

I’m not saying I agree with them. But yes, that’s what they seem to be claiming. Here is Stephen Williamson, for instance, saying the Fed can never lift asset prices. Like SW, modern NKs assume a 100% efficient Wallace-style economy in which OMOs are irrelevant at the ZLB. Compared to them, you’re a softy on efficiency.

10. February 2013 at 22:02

Scott,

Yes, we can say that about basic S&D, but the difference is that we need to keep in mind that showing whether Hedge Funds (or any other style of management) outperform the market after fees tells you nothing about the efficiency of the market. The fees themselves do. Consequently, if equity hedge funds can get away with charging 2/20 for decades, it means that the cost structure gives you a rough measure of inefficiency of the equity markets (along with their market share). Same applies to bond or any other class of assets. So, equity and bond markets are somewhat efficient, but not that efficient (depending on how much of the global equity/bond investment is controlled by hedge funds).

11. February 2013 at 20:17

“Fed up. Of course people were surprised! Didn’t all of the media tell them that Obama was only raising taxes on the rich?”

And you just proved my point. If EMH was true, people would double check what the media says, what the President says, and what both parties say.

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2012/11/a-few-thoughts-on-fiscal-agreement.html

“2) The payroll tax cut is probably going away. This was the 2% payroll tax reduction that workers received in 2010 and 2011. For a family with a $50,000 per year income, this is a tax increase of about $20 per week.”

11. February 2013 at 20:24

Another one.

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2012/12/fiscal-agreement-update.html

“This means the payroll tax cuts would expire (something I’ve expected) and tax rates for those making more than $250,000 would increase (also expected).”

You can also google “site:calculatedriskblog.com payroll tax 2013”

11. February 2013 at 20:32

“Fed up, And what about all the other European and Asian countries that saw big price run-ups, but no crash?”

Someone would need to go thru the details of each country one by one.

11. February 2013 at 23:47

Here is another one.

The Importance of Excel (JPM london whale trade)

http://baselinescenario.com/2013/02/09/the-importance-of-excel/

“This is why the JPMorgan VaR model is the rule, not the exception: manual data entry, manual copy-and-paste, and formula errors. This is another important reason why you should pause whenever you hear that banks’ quantitative experts are smarter than Einstein, or that sophisticated risk management technology can protect banks from blowing up. At the end of the day, it’s all software. While all software breaks occasionally, Excel spreadsheets break all the time. But they don’t tell you when they break: they just give you the wrong number.

There’s another factor at work here. What if the error had gone the wrong way, and the model had incorrectly doubled its estimate of volatility? Then VaR would have been higher, the CIO wouldn’t have been allowed to place such large bets, and the quants would have inspected the model to see what was going on. That kind of error would have been caught. Errors that lower VaR, allowing traders to increase their bets, are the ones that slip through the cracks. That one-sided incentive structure means that we should expect VaR to be systematically underestimated””but since we don’t know the frequency or the size of the errors, we have no idea of how much.

Is this any way to run a bank””let alone a global financial system?”

12. February 2013 at 11:42

[…] recent days two blogs that I like to read posted about the subject (The Money Illusion and Noahpinion). Both posts are well worth a read as they provide a few nice examples, which at […]

13. February 2013 at 00:53

[…] dalingen uitzonderlijk, waarbij dit patroon bewijst dat de stijgingen ‘rationeel’ zijn, waarmee maar weer bewezen is dat markten ook rationeel zijn, in de zin die (neo-klassieke) economen hieraan geven. Of zou er toch sprake zijn van […]

13. February 2013 at 01:06

[…] are quite exceptional, which proves that the housing market is rational in the neo-classical sense, which proves that markets are rational in the neo-classical sense. Is he right? Or might the housing market be characterized by ‘house price illusion’, […]

13. February 2013 at 03:32

[…] quite exceptional, which proves that the housing market is rational in the neo-classical sense, which proves that markets are rational in the neo-classical sense. Is he […]

13. February 2013 at 18:21

[…] Blogger cites an older (misinformed ) Economist article citing an academic study (rubbish) as support for Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) here: http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=19209. […]

23. February 2017 at 06:06

[…] http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=19209 […]