The USA doesn’t have any debatable recessions. That’s about to change

The US has a really weird economy. All our recessions are 100% clear-cut. Either we have a recession or we don’t. Normal countries have borderline recessions. Not us. Either our unemployment rate rises far too little to be viewed as a recession, or so much that 100% of economists agree it’s a recession. I don’t know why that is. And I don’t know why other economists don’t view it as really weird. Maybe people just notice things that happen, not things that don’t. Not dogs that don’t bark.

I believe this weird pattern is about to end, and very soon we’ll have debatable recessions. This post is partly motivated by my previous post on Japan. I don’t think people realize how much changes when your trend rate of RGDP growth becomes zero, or even negative. Some pointed to the fact that Japan is “weird” because unemployment rose very little in the 2007-09 recession. Sorry, but Japan is now pretty normal; it’s the US that is weird. Here’s some crude data using annual changes in RGDP and the rise in unemployment from the 2007 low to the 2009 high. Note that Germany’s recession was confined to 2008-09:

Japan: Drop in RGDP = 6.5%, Rise in unemployment = 2%

Germany: Drop in RGDP = 5%, Rise in unemployment = 2%

Britain: Drop in RGDP = 5.5%, Rise in Unemployment = 2.8%

USA: Drop in RGDP only 3%, Rise in Unemployment = 5.5%

Quarterly data would be slightly better, but wouldn’t change the overall pattern. A relatively large fall in RGDP in other countries doesn’t lead to much extra unemployment. That’s partly lower trend RGDP growth (Germany and Japan have falling populations) and partly the more flexible US labor market.

And now it looks like the US trend rate of RGDP growth will fall from 3% to barely over 1%. After we “recover” it will no longer be unusual to see two straight quarters of falling RGDP. But will they be true recessions? Or the sort of phony “recession” that people think they are seeing in Japan, and that was reported in the UK a couple years ago, which later vanished with revisions in the data? (I’m referring to Britain’s triple dip; even the double dip was very debatable, with only a 1/2% rise in unemployment.)

Is it possible I’ll be wrong about the US trend growth? Sure, a change in immigration policy, or supply side reforms to boost the LFPR could help, but I don’t see much sign of that happening. The prime age workforce will soon stop growing, and productivity growth is slowing as well. Get ready for lots of phony “recession” stories, especially when the party in power is not well liked by the intelligentsia. (Which party would that be in America?)

PS. I believe I was the first blogger to blow the whistle on the phony 2011 tsunami “recession” in Japan. I’m still waiting for the delayed unemployment effect from the tsunami . . .

Japan has supposedly been in recession for 7 months—I’m sure their unemployment rate will soar any day now. Especially with Japanese firms complaining they can’t find enough workers to fill the job openings.

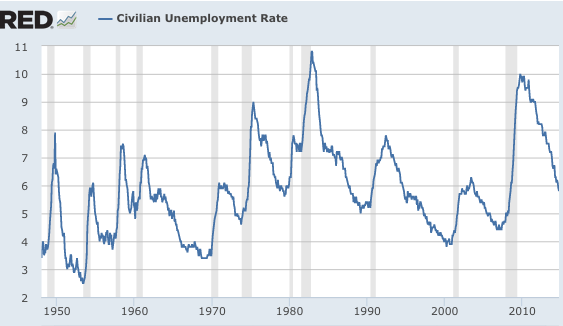

Update: For those that have trouble understanding why there are no debatable recessions, consider the following graph. During an actual recession, unemployment rises by at least 2%. When there is no recession the biggest rise was 0.8% in 1959 (nationwide steel strike) and that was really brief. Look at that tiny spike in 1959, then look at the actual recessions, and marvel at the vast difference.

Note how different it is from a random walk graph (like the stock market) where you see small, medium and large fluctuations. All we see are small and large, no medium.

Tags:

17. November 2014 at 22:22

Prof Sumner,

r Germany’s monetary conditions loose (because the DM would b worth much more than the peseta, say) under the Euro, while Spain’s r too tight under the same currency?

to clarify, I’m not a smart-alec trying to stump u

18. November 2014 at 04:34

Lower output does not cause unemployment. Ceteris paribus the causation goes the other way.

If technological progress slows, or capital is consumed, because of inflation, that can reduce output without any increase in unemployment.

18. November 2014 at 05:45

I suspect the tight-money fanatics will posit sloggy growth is the new normal, not a recession, and brings with it the salvation of dead prices.

18. November 2014 at 05:55

Dawson, I don’t regard German monetary conditions as being loose. They are probably roughly appropriate for Germany, given the low inflation preferences of the Germans. But it is debatable whether those low inflation preferences are wise. Even if they had the DM, they’d face the zero bound problem, and be unable to use interest rates. That’s not necessarily a problem, but the Germans seem opposed to QE. So what policy do they want their central bank to use in order to maintain price stability?

18. November 2014 at 06:52

Doesn’t the 2001 recession qualify as debatable? It was a big change from the recent trend, but going by BEA data, annualized RGDP was $12.68B, $12.64B, $12.71B, $12.67B, and then growing again, albeit slowly.

18. November 2014 at 07:04

Germany was in near recessionary conditions from Q4 2011 to Q1 2013.

The growth rates by quarter are:

Q4 11: 0.0%

Q1 12: 0.31#

Q2 12: 0.12%

Q3 12: 0.09%

Q4 12: -0.41%

Q1 13: -0.40%

By US standards, Germany was in recession from late 2012 to early 2013. But essentially, one could write of this whole period as the response to the Fourth Oil Shock of April 2011.

You can find the same effect in the US. See for example, ECRI’s WLI Index, US oil consumption, 2 and 5 year interest rates. All of these suggest a crypto-recession in the US as well. The difference was, of course, that shale oil and gas production in the US was surging at the time.

18. November 2014 at 07:07

I think the more pertinent question is the upcoming call on US interest rates.

There are some quite contradictory and confusing inflation numbers for October (out today) and expected lower unemployment rates.

I’d probably leave interest rates alone for another quarter, preferring to err on the side of higher inflation for the moment. I’d add that the employment data would suggest wage inflation by mid year 2015 or so.

18. November 2014 at 07:34

Where is the 1% RGDP figure coming from?

18. November 2014 at 07:51

Robert, See my update, I strongly prefer unemployment to RGDP as a cyclical indicator. I know of no economist who doesn’t consider 2001 to be a recession, albeit a mild one.

Steven, Good find. That shows the folly of relying on RGDP for a country with a falling population. Obviously Germany was not in “recession” by any meaningful definition of the term. Their labor market is really tight.

Jesse, My most recent estimate of US trend RGDP growth is about 1.2%, almost all due to productivity. Of course I may be wrong–especially if employment among the elderly keeps rising.

18. November 2014 at 08:00

Clearly, if population is falling, then it’s race between demographics and productivity.

I might argue that Germany is in a crypto-recession of its own owing to trade effects associated with Russia resulting from the conflict with Ukraine.

Germany last two quarters growth:

Q2 2014: -0.16%

Q3 2014: 0.10% (Eurostat “flash” numbers, for whatever that’s worth)

Here’s the post (also linked earlier): http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/11/14/q3-euro-gdp-stagnation-russia-or-oil

Let’s let the lower oil prices run through for a while. If a supply-constrained model is right (and assuming Ukraine doesn’t deteriorate, which it could), we should see a pretty nice recovery in Europe, which we’re already seeing in the PIGS. We should also see pretty good growth in the US as well, maybe high 2’s to mid-3’s.

On the other hand, if low oil prices don’t stimulate GDP over the next year, well, then I’m wrong.

18. November 2014 at 08:01

Fair enough. I will say that more than half of the rise in the unemployment rate came after the official end of the recession. At the very least it was a weird for the US recession, even if generally agreed upon.

18. November 2014 at 08:04

Finally, we need to keep in mind that RGDP numbers are important in national terms.

Government debt is an aggregate obligation, so slowing demographics imply lower sustainable deficits, all other things equal.

Also, growth allows Ponzi-type redistributive schemes, a la Social Security. Once you’re declining, then the ability to redistribute income may actually be declining over time. A reverse Ponzi scheme, if you’ll have it.

18. November 2014 at 08:42

Two reasons why the US economy is so “Weird”:

1) The economy is so big and varied that there is always a growing market. Dotcoms bust, go to Housing. Housing busts, Move to North Dakota to Frack and drill oil! The flexibility and laborforce allows for a lot more balance in the economy. (I still say economist are underestimating the Euro problem of a less flexible labor force. Just think what would happen if Italians were moving to Germany more.)

2) The biggest global joke of the US Financial Crisis was the US economy is simply “Too Big To Fail” as well. Think about all the events in the 2008 Crisis: We changed leaders, most the largest financial were insolvent, record foreclosures, the Government passes TARP, have a huge trade deficit, etc. And after all that, the Currency jumped up for six months.

18. November 2014 at 09:11

The public debt owed to the public of Germany and other Eurozone countries is an entirely different proposition in terms of ‘sustainability’ than that of the U.S.A., the U.K., Japan, et al nonconvertible, floating exchange-rate, fiat (n-cff) currency issuers.

All these discussions of Social Security as “Ponzi-type redistributive schemes’ are figments of people’s imagination.

Until and unless people wake up to the elementary differences between n-cff currency issuers vs others (currency users) these discussions will be muddled.

18. November 2014 at 10:34

We don’t do a very good job measuring unemployment, so it’s difficult to draw any conclusions for the number.

The cynic in me believes the government is deliberately fudging the numbers, and economists are too lazy to study the numbers so they just go along with it.

Most people who are not working or working fewer hours than they wish just don’t show up in the employment numbers. It bothers me that economists see this, but instead of putting the real numbers into their formulations they just go along with the official numbers.

18. November 2014 at 12:11

Gkr –

The Ponzi aspect of US Social Security is well-established and not controversial. In the beginning of Social Security, people died younger and the population was growing quickly. Therefore, SS could be expanded and benefits increased.

For the self-employed, the SS rate is now 15.2%–there’s not much upside left there. Further, if your population is living longer and there are fewer children, then your ability to increase, or ad absurdum, hold per capita Social Security payments steady comes into question. This has the potential to change political dynamics over time. For example, the young may come to perceive it as a rip off, and that may erode support for the program.

GDP growth, or the absence thereof, can materially change the political context for policy-making (but in either direction). I think that’s important to understand. A lot of socialist programs (eg, unfunded public sector pensions) turn out to be unsupportable Ponzi schemes when left to run long enough.

I would add that taxes are a big chunk of the OECD economies. Kevin says that Japan’s spending isn’t that big–and it’s not by French standards–but giving the dead hand of government 40% of GDP to play with–well, do you think that might crimp GDP growth? I do.

I’d also add that I think we’re being a bit blasé about the size of Japan’s chronic deficits. Do we really believe that a country can run a 6.5% budget deficit for twenty years with no impact on growth? Is that plausible? It’s something akin to saying, “I showed up for work every day for twenty years stoned, but it didn’t impair my performance.” We sure about that?

It’s not that I disagree about demographics, but golly, there’s more in the Library than just Colonel Mustard with the lead pipe. There are a lot of questionable policy choices that deserve far more scrutiny than we’ve given them.

18. November 2014 at 14:10

Robert, As I recall RGDP and NGDP growth was quite low in 2002–not much of a recovery.

Collin, Don’t forget that money was very tight in late 2008, which also pushed up the dollar.

18. November 2014 at 17:23

If we had the kind of monetary policy you recommend (and I agree with) with NGDP expanding at 4%-5% would you expect RGDP to grow at only 1%? Even leaving aside the arbitrary upper limit of “working age” why would you expect productivity to fall? What are you assuming about public investment? What if it started to behave “orthodoxly: investing in project with positive NPV?”

BTW you have another supporter of NGDP targeting, Brad DeLong:

“As you know, I am of the view that the Federal Reserve ought to be following feedback rule by which it should add to its balance sheet when nominal GDP is below its target and reduce its balance sheet nominal GDP is or imminently threatens to rise above its target.”

http://equitablegrowth.org/2014/11/17/confess-understand-argument-taper-long-inflation-target-monday-focus/

18. November 2014 at 22:29

For this non-economist it seems that the US has a strong positive feedback (called by economists procyclical, right?) somewhere in the factors determining employment…

19. November 2014 at 04:50

D. O.,

Some positive feedback features like that are uncontroversial in economics e.g. that labour productivity is procyclical.

19. November 2014 at 04:51

Usually, of course. In the early 1980s in the UK, there was a big countercylical labour productivity boost due to Thatcher’s reforms.

19. November 2014 at 05:23

Thomas, Over the past 5 years our unemployment rate has been falling fast, and yet we’ve only grown at a bit over 2%. Soon our unemployment rate will stop falling, and growth should slow sharply to the new trend, whatever it is.

D.O. That could be, I don’t fully understand the pattern.

19. November 2014 at 06:40

And whom did you hear it from first?

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-11-19/wages-poised-to-rise-as-signs-emerge-of-improved-u-s-job-market.html

19. November 2014 at 09:55

Collin, Don’t forget that money was very tight in late 2008, which also pushed up the dollar.

Yes, my memory was of 2008 was most investors did not believe money was tight for most of 2008. Their beliefs were that money was too loose and for a lot, like Peter Schiff, this was the great comeuppence of the US economy and society. (Didn’t you debate him on reality of inflation?) Even if you assume money was too tight in summer of 2008, it still strikes me as really weird that a country has a huge financial crisis, record foreclosures, and huge increases in debt would have its currency increase in value short term. Not only is the US economy “Too Big To Fail”, in many ways the US is ying to the global economy yang in terms of growth. During the 1990s the US economy grows like crazy and there is the Asian flu, Russian currency crisis, and slow Europe. In the 2000s, the US economy is way overheating (it took 7 years to go out) while the rest of the world grows like crazy. Now since 2008, everywhere else not named China has had a slowdown while the US has decent growth.

Why has the unemployment dropped so much compared to slow growth and productivity? One real wages continue to slightly drop. Also we are seeing the reverse of Michael Mandel’s theory that early 2000 off shoring made the US productivity increase artifically high. (So we able to sell a $500 ipad after paying China $10 which made the productivity gains really high.) Although manufacturing has not come back, but there is on shoring of office and call center positions.

19. November 2014 at 14:46

When looking at RGDP and Unemployment alone for the U.S., I agree. The only debate is the beginning of the 1957 recession (did it actually begin more than a year before the NBER says it did?). When looking at investment and Industrial Production, there were clear slowdowns in 1952 and 1967 which are not counted as recessions due to high government spending and military conscription during these periods.

19. November 2014 at 20:15

Maybe the ‘weirdness’ of our economy is something conservatives can take credit for. What it seems to amount to is that we lose a lot more jobs during a recession than other similar countries thanks to our more ‘flexible’ workforce-ie, it’s much easier to fire workers here than elsewhere, certainly than in Japan, which is the opposite extreme of our ‘flexibility’

19. November 2014 at 20:17

Ok I see now you mentioned flexibility up there but I hadn’t noticed it before my comment.

20. November 2014 at 07:56

The factor that you didn’t mention in this post is that the U.S. is one of the few developed countries with solid population growth. Japan, which is in population decline, is bound to have more “Near-zero” years in terms of real GDP growth, because that still means that per capita GDP growth is positive. It also goes a long way towards explaining why unemployment doesn’t necessarily go up as quickly.

20. November 2014 at 17:47

E. Harding, If you look at all the data for 1967 it wasn’t even close to being a recession year. IP is one sector, but both RGDP and employment were strong. I don’t recall 1952.

Adam, Yes, I mentioned that as a factor, maybe in the earlier post.

30. November 2014 at 10:01

@Scott Sumner

“If you look at all the data for 1967 it wasn’t even close to being a recession year.”

-Agreed. I still reserve the right to call it a slowdown, though. It was, perhaps, the only time in U.S. history when the yield curve flipped and real M1 fell, yet no recession occured (only a “credit crunch”).

30. November 2014 at 10:37

Maybe, But the yield curve gave false alarms in 1988 and 1997, as I recall. Don’t know about M1.