The out-of-sample properties of David Glasner’s conjecture

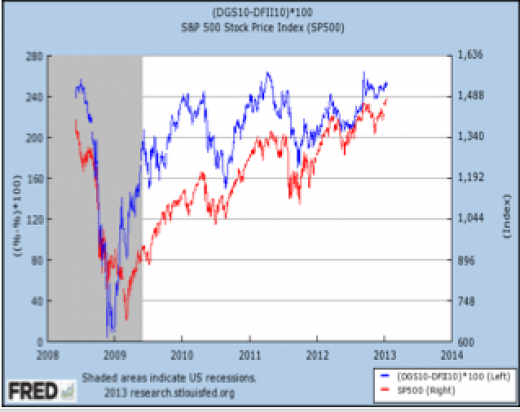

In late 2010 David Glasner did a study showing that TIPS spreads and stock prices became highly (and positively) correlated around 2008. Previously the correlation had been rather weak. The most plausible interpretation is that the stock market began to root for higher inflation (and by implication higher NGDP) at about the time when the US economy began to suffer from a demand shortfall. Michael Darda sent me a graph showing that more that two years later the correlation persists:

It’s easy to data mine enough time series to find spurious correlations. It’s much harder to develop a model that continues to do well after the results are published. It looks like David Glasner’s model passes that test.

Tags:

6. February 2013 at 09:03

If you put in relevant dates the chart becomes even more impressive. The reversals associate perfectly with things like QE1 (on) QE1 (off), Hint QE2, QE2 (off), Op. Twist, QE3 etc

6. February 2013 at 09:05

Strange that you leave the Fed’s response to inflation out of your interpretation. The stock market is “rooting” for inflation because it thinks the Fed will not tighten.

But the Market Monetarist story is that the Fed is getting exactly what it wants (no liquidity trap), and so there would be no reason to root for inflation, since it would only bring on Fed tightening and possibly recession.

6. February 2013 at 09:05

While I am not surprised by this correlation, I do disagree with your conclusion — that stock prices are “rooting” for higher inlation.

I would say that changing expectations for NGDP growth should lead to both higher inflation expectation and higher expectations of revenue growth.

6. February 2013 at 09:41

Krugman defends his views on Japan, calls BoJ “too cautious” (HT Tyler Cowen) http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/02/05/the-japan-story/

Basically Krugman now seems to be defining “liquidity trap” as the same thing as “ZLB”. He still says the way out is to promise greater inflation in the future, but is now not so much saying they were impotent, as that they didn’t have enough commitment, to wit:

No comment though on how easy it was to depreciate the Yen recently when signs of expansionary intent emerged.

6. February 2013 at 09:53

Stock markets pleading for more NGDP. Interesting.

Saturos — Yep, those claims of monetary authority impotence always seemed either disingenuous or poorly thought out.

6. February 2013 at 10:38

Speaking of time series and interesting correlations, surely all have noticed the remarkable performance of the Nikkei since around mid November? It’s up over 25% (and yes, other indices are up as well, but not nearly so dramatic). Surely this has people conceding that the BOJ both could have and should have been doing something earlier?

6. February 2013 at 12:26

Marcus, That’s why we need you!

Max, I don’t think I’ve ever said the Fed gets exactly what it wants. But in any case if it does then what it wants must change over times, and the stock market likes to see it change in the direction of faster NGDP growth.

Doug, That’s right, I stand corrected. And indeed inflation probably hurts stock prices, but higher NGDP growth helps even more.

Saturos, You quote Krugman as saying:

“…the Bank of Japan has always pulled back on monetary policy when the economy looks better, instead of doing what it should, which is to keep the pedal to the metal until the inflation rate is solidly into positive territory.”

That was the argument I kept using against him when we debated. He said the BOJ tried to inflate and failed, and I kept insisting they pulled back whenever inflation rose to zero. (from negative.) Now he’s almost more monetarist than I am.

John, I posted on that the very first day of the rally.

BTW, It’s up over 30%—amazing.

6. February 2013 at 13:11

Perhaps it is not that higher expected NGDP growth is driving inflation expectations and revenue expectations. Krugman would argue that, at the ZLB, higher expected inflation translates one-for-one to lower expected real interest rates, which boosts stock prices.

Also, to be fair to Krugman, I think he always qualifies ‘monetary policy is ineffective at the ZLB’ with ‘conventional monetary policy is ineffective at the ZLB.’ He seems to agree that more would be better, but just doesn’t think it will happen or isn’t as confident in unconventional policy as NGDPLT supporters (unconventional in the sense that it isn’t about lowering the nominal short-term interest rate).

6. February 2013 at 13:47

Prof. Sumner,

Isn’t this using the flawed logic that correlation implies causation? You did point to the fact that this could be a spurious correlation, but still. Correlations in economic data shift all the time for many different reasons. I think it’d be very difficult to say that the market was rooting for higher inflation just because the correlation increased.

6. February 2013 at 15:09

How do we get more policy makers to engage on market monetarism?

Its nice Darda gets a new view out there but man most pointed headed economists are clueless.

Hai

6. February 2013 at 16:07

I’d like to add a point to the Japan argument. It’s too late for Japan to ramp up inflation. Their interest rates cannot shift at all. They already spend 50% of their revenues on debt service. A 200 basis point shift in their rates and their expenses explode; the expenses would then be greater than their revenues. There is a nonlinearity that develops between expenses and revenues when your debt is 25 times your revenue. The problem is that Japan’s situation could get out of hand very, very quickly. The situation will depend on the behavior of the market and when the market realizes that Japan’s situation is simply unsustainable. If Japan tries to inflate their way out of their problems, their problems get much, much worse.

6. February 2013 at 16:27

Interesting that the graphs diverge substantially a couple months before January 2013. Fiscal cliff?

6. February 2013 at 18:29

Has the stock market has been “rooting” for more inflation since 2008, or has the stock market become dependent on more inflation since 2008?

6. February 2013 at 19:08

J, I think that’s about right, but the pedal to the metal comment seems slightly unKrugmanlike. See what you think of my next post.

Suvy, Sure, but most economic studies just look at correlation. When you have a model that implies time-varying correlation, and you get exactly the time-varying correlation predicted by the model, it’s more powerful empirical eivdence than you see in most studies.

And inflation still helps debtors, as I keep pointing out.

Travis, Yes, the deeper drop in stocks may have been the cliff scare.

6. February 2013 at 20:00

Is Suvy an alias for Geoff or do they both suffer from the same peculiar form of money illusion – call it balanced budget illusion – the belief that deficits as such are unsustainable, even if debt is forever declining as a % of revenue.

6. February 2013 at 20:38

“Is Suvy an alias for Geoff or do they both suffer from the same peculiar form of money illusion – call it balanced budget illusion – the belief that deficits as such are unsustainable, even if debt is forever declining as a % of revenue.”

The government’s debt/GDP ratio has been rising in Japan ever since around 1990. You add in the fact that Japan has a falling population and a falling workforce. They spend 50% of their tax revenues on debt service and 65% of their revenues on social security. Add this to the fact that they have less and less people working due to a falling population and all of those people need to be taken care of. What makes Japan’s situation unsustainable are the country’s structural problems. You can’t take care of more and more people when you have less and less people working and less and less people able to work; it’s unsustainable.

6. February 2013 at 20:44

“And inflation still helps debtors, as I keep pointing out.”

It depends on the level of debt. If I am moderately indebted and paying down my debt, then yes, inflation does help as it provides me an extra cash flow to pay down my debt even if my interest rates increase. However, if I’m highly indebted where I am relying on taking more debt on to pay of my old debt(rolling over my principal payments), then the shift in interest rates from higher inflation would doom me.

7. February 2013 at 01:44

Suvy — The proposal is not that Japan inflate its way out of its debt problems, but rather that the central bank expand the money supply to increase NGDP and create inflation. Investors might see this as a way to reduce the nominal value of the debt and get nervous, or they might see this as a way for the Japanese economy to begin growing again and feel more reassured. I might argue the converse of what you’re saying: that if Japan continues to do nothing, then eventually investors will realize that Japan HAS to inflate its way out when the debt-to-GDP ratio is at an even higher level and GDP is still not growing.

Moreover, you are right that a nominal interest rate increase could be very bad for Japan, but, at the ZLB, why would that happen? Particularly if inflation is caused by expansionary monetary policy (which pushes short-term nominal rates down), then it is likely that the inflation will just push real rates down. Maybe long-term nominal rates will go up, but that will only be because investors expect more growth in Japan, and once again might feel reassured by that, not nervous.

7. February 2013 at 05:41

Suvy, Inflation does not increase real interest rates.

7. February 2013 at 06:37

“Suvy, Inflation does not increase real interest rates.”

It doesn’t have to. It’s basic math. Debt service costs don’t move linearly with a rise in interest rates when the principal is regularly being rolled over while revenues do. That’s the central problem. On one side, you have compounding effects coming from exponential growth while you have linear growth on the other. That’s the precise problem when you have debt that is 25 times your revenue. That’s why the amount of principal that is rolled over is essential as is the term structure of the debt.

7. February 2013 at 06:53

J,

What happens when the market participants realize what’s going on. What I think is likely to happen is that, all of a sudden, you’ll see a whole lot of JGBs being sold off all at once. Then, the BOJ will have no choice but to come in and buy all of those JGBs if they want to keep interest rates at the ZLB, but this cannot be controlled like people think it can. Eventually, inflation is going to take off. This is because you can control either the money supply or the rate of interest, but not both. So if they control the money supply to try and contain inflation, at some point, interest rates take off. If they try to keep interest rates near zero, inflation takes off. It just depends on when the behaviors of the people involved in the situation change.

Now, I also agree that if Japan doesn’t do anything, they’re screwed too. Japan is screwed regardless. Japan’s situation is simply unsustainable. I think the best solution for Japan would be to default; however, I think Japan gets stuck in an inflationary scenario at some point in the next 5 years regardless of whether or not they take up monetary expansion. They may be able to kick the can down the road for a bit longer, but they’re doomed.

Japan is basically running a Ponzi scheme. They were able to finance themselves with their high savings rates and large current account surpluses for around 20-25 years. However, their savings and investment rates have now collapsed while their current account has just hit a negative. Eventually, the market for JGBs will collapse and all of that debt will have to be monetizes; probably all at once when the market participants realize what’s going on.

7. February 2013 at 10:16

Suvy,

I would love to take an even odds bet that Japan does not have runaway inflation (let’s say over 6%) in the next five years.

7. February 2013 at 11:45

J,

I don’t know when Japan will have runaway inflation. I think it’ll be within 5 years; however, I could be wrong on the timing. The timing is impossible to get. All I’m going to say is this: the road they are headed on is simply unsustainable. If something is unsustainable, it will stop.

Who knows, they might start letting lots of immigrants entire while simultaneously imposing massive reform and restructure some of their debt to avoid the scenario. That’s not what I think is gonna happen, but it could.

As for the bet, I would take the other side of that bet.

7. February 2013 at 14:34

Scott, Thanks for this post, and for the graph. I have been procrastinating in updating my paper, perhaps this will get me on the ball.

Suvy, If you read my paper, you will see that there is in fact a theory explaining the causal relationship between expected inflation and asset values when the real rate of interest is less than the expected rate of deflation. We got into that situation in 2008 and have been struggling to escape from it ever since. That’s why you only observe the correlation in periods of low inflation and low real interest rates.

7. February 2013 at 16:21

David Glassner, You said;

“when the real rate of interest is less than the expected rate of deflation”

If real rate = nominal rate – inflation, then isn’t this mathematically just

nominal rate – inflation < inflation, or

nominal rate < 0

7. February 2013 at 18:54

dtoh,

There is no law of nature that prevents people from expecting a rate of deflation greater than the real rate of interest. But if that is what people expect, it will have repercussions, e.g., crash of asset prices because people try to sell real assets in order to hold money which they expect to have a higher yield than real assets. Unless expectations go haywire, and the economy falls into a black hole, the expected rate of deflation will not long exceed the real rate of interest. My conjecture is that, since 2009 when the stock market bottomed out, the real rate of interest has been uncomfortably close to the expected rate of deflation, which is why anything that reduces the expected rate of deflation is good for stocks.

7. February 2013 at 19:33

David,

There is no law of nature that prevents people from expecting a rate of deflation greater than the real rate of interest.

Not disputing this or the repercussions. I’m just asking isn’t (rate of deflation greater than the real rate of interest) mathematically equivalent to nominal rate of interest < 0?

7. February 2013 at 20:41

dtoh, Sorry. You’re right. But a nominal rate of interest less than 0 would violate a law of nature, so the adjustment has to proceed by way of a different route.

8. February 2013 at 06:45

Suvy if real rates don’t rise I don’t see the problem.

8. February 2013 at 06:52

David,

It’s interesting you say that because I was looking at it from a different perspective. In late 2007-early 2008, the threat was not inflation; the real threat was a debt deflation. The threat was mass liquidations leading to plunging asset prices leading to deflation and thus more liquidations. What QE did was prevent that feedback loop from taking place. Of course, I’m referring to Irving Fisher’s theory of debt deflation.

I skimmed your paper and it seems like you reach the same conclusion by using the expectations of future cash flows and its relation to the nominal and real interest rate in deflationary environments. Basically, you’re saying that the increasing asset prices came from the shift in expectations of future cash flows. It’s very interesting; I never thought about it that way.

8. February 2013 at 12:47

“Suvy if real rates don’t rise I don’t see the problem.”

The problem is that debt service costs don’t move the same way that incomes do with respect to inflation. If you have 5% inflation which leads to a 10% increase in tax revenues, while the nominal rate shifts by 3%; the debt/income ratio plays a critical role. This is because your debt service costs move much higher with a 3% move in your interest rate when your debt/income ratio is higher. The higher the debt/income ratio, the more your debt service costs move. Therefore, when you have a debt/income ratio fo 25(like Japan) and spend 50% of your tax revenues on debt service, if your interest rates shift by 2%, you go completely bust.

10. February 2013 at 13:53

Suvy, Your real debt service costs don’t rise.

10. February 2013 at 20:09

“Suvy, Your real debt service costs don’t rise.”

Yes they do. Debt service costs depend on debt/income ratios. For example, say there are two people that have an income of $10/year and one has a total debt of $20 while the other had a total debt of $200. Let’s assume that their incomes rise by 10% with 5% inflation; however, their interest rates rise 2%. Both now have an income of $11/year; however, the 2% rise in interest rates will almost surely blow the second person up while the 2% rise in interest rates for the first person won’t be too big of a deal.

Japan is in the situation of the first person. Japan spends 50% of its tax revenues on debt service(half of which is on interest); let’s say that Japan’s inflation increases by 3% causing a 7% rise in revenues(very generous assumption), while their interest rates shift by say 75 basis points. The problem is that when your debt/income ratio is 25, your cost of capital is much higher and I’m sure Japan’s cost of capital is much higher than 10%. I don’t know where I can get Japan’s WACC, but if you could point me to some data on it, you could calculate exactly how much of a shift in interest rates it would take for Japan to blow up.

10. February 2013 at 20:12

Basically, if the cost of capital increases more than your income from a shift in rates, then inflation may actually blow you up. I think Japan has actually crossed that threshold where inflation is not a solution.

10. February 2013 at 20:18

That previous comment was poorly stated. The sensitivity of debt service costs to interest rates is determined by the cost of capital. If your cost of capital is beyond a certain point(and cost of capital depends heavily on debt/income ratios), you’re doomed.

12. February 2013 at 09:59

Suvy:

“Yes they do. Debt service costs depend on debt/income ratios. For example, say there are two people that have an income of $10/year and one has a total debt of $20 while the other had a total debt of $200. Let’s assume that their incomes rise by 10% with 5% inflation; however, their interest rates rise 2%. Both now have an income of $11/year; however, the 2% rise in interest rates will almost surely blow the second person up while the 2% rise in interest rates for the first person won’t be too big of a deal.”

“Japan is in the situation of the first person.”

Only if the indebted person keeps borrowing. The $20 and $200 of debt are “locked in” a series of interest and principle payments.

If interest rates rise, the person who is indebted $200 won’t have to pay higher interest payments unless he rolled his debt over (meaning he paid back his old debt by issuing new debt). But then who would lend $200 to a person at such a high interest payment to income ratio? I know I wouldn’t lend $200 to you at a significantly high interest rate if your annual income is only $20.

I am more inclined to agree with you with you about Japan however, because it is far more difficult for a state to reduce its borrowing rate after a build up during “peacetime”. If Japan’s interest costs rose because they those chose the route of significant inflation, then they would be forced to borrow a lot less than before, and that would upset a lot of those dependent on such borrowing (and spending). Japan’s a democracy so with a sizable enough dependency in the population, it isn’t as easy as “We’ll just print money to pay back old debts, and not issue as much new debt going forward”.