The New Yorker on monetary policy

I recall the New Yorker used to advertise itself as “the best magazine in the world.” I think it’s fair to say that this was not based on its economics reporting. Gordon sent me the following:

At the end of last year, when jobs and output both appeared to be growing strongly, members of the F.O.M.C. were predicting that G.D.P. growth in 2015 would be somewhere between 2.6 and 3.0 per cent. Now they have cut their prediction for growth this year to somewhere between 2.3 and 2.7 per cent. That’s not a drastic revision, but it reflects a number of recent economic statistics, such as retail sales and exports, having come in weaker than expected. Yellen pointed to a subdued housing market and a stronger dollar as restraining factors.

While Yellen was at pains to point out that other recent indicators, notably jobs numbers, have remained strong, the big rise in the dollar over the past year clearly has Yellen’s attention. Indeed, I suspect that the rally in the currency has prompted a serious rethink inside the Fed””and for good reason. The rise in the dollar means, effectively, that monetary policy has already been tightened. From an economy-wide perspective, an appreciation of the currency acts just like an actual rise in rates: it reduces the over-all level of demand and causes a slowdown in G.D.P. growth. Now that this has happened, it’s no surprise that the Fed would reconsider its next move.

To put it another way, the currency markets have already done a bit of the Fed’s work for it. By signalling to the market over the past few months that it was preparing to raise rates, the Fed prompted currency speculators to buy dollar-denominated assets, which bid up the price of the U.S. currency. Since this time last year, the value of the dollar against the euro has jumped by almost thirty per cent.

I can’t believe the Fed is downgrading its growth forecasts for 2015, who ever would have expected that to occur? (Does anyone recall the last time they didn’t have to do that?)

More importantly, a rise in the dollar is most certainly not equivalent to a tightening of monetary policy. If it was, then the dollar exchange rate would be the proper measure of the stance of monetary policy, not interest rates, real interest rates, the monetary base, M2, er, I mean NGDP growth expectations.

Perhaps the most incredible claim is that the dollar’s recent surge is due to the Fed signaling an intention to raise rates later this year, as if the market was not fully aware of that fact back when the euro traded at $1.35. The new information in the last year has been monetary stimulus out of Europe (and probably some other things that I’m not aware of.)

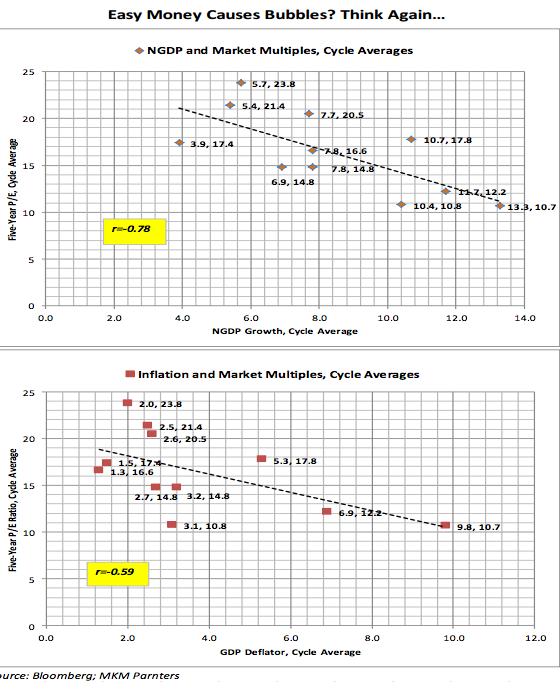

In another New Yorker article John Cassidy suggests that, “the threat of bubbles, not inflation, should guide Fed policy.” This despite the fact that the Fed’s last effort at bubble popping (in 1929) didn’t work out so well. Not to mention that there is essentially no evidence as to what causes bubbles, which are not generally associated with easy money policies. Michael Darda recently sent me a graph showing that “overvalued” markets are actually more likely to occur when money is tight:

Tags:

20. March 2015 at 13:50

Three weeks ago, I had conversations with Joe Leider and Kevin Erdmann on the “optimal” rate of NGDP growth for stock valuations:

http://joeleider.com/economics/the-division-between-capital-labor-part-ii/#comment-15

http://joeleider.com/economics/the-division-between-capital-labor-part-ii/#comment-16

20. March 2015 at 13:55

Kevin Erdmann and I also had a good discussion of NGDP growth and valuation multiples in this comment section:

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-huge-potential-value-of-ngdp-level.html

20. March 2015 at 14:07

“the best magazine in the world.”

Best means better than others. Something can be very low quality and still be the best.

What general magazine do you think does the best job of economics reporting?

20. March 2015 at 14:08

Cool charts. Thanks for sharing.

20. March 2015 at 14:38

If the fed signals that it intends to contract the monetary base / raise interest rates / tighten money, and the market reacts to this changing information, or the market interprets changing economic variables that the Fed will tighten, the market will position itself for tighter money. The market is forward looking. Or, you could say, they market is informationally efficient.

A change in the potential for the Fed to tighten, causes the market to react as if the Fed has tightened, causes money to be less available. The rumor of a tightening is, in fact, a tightening.

If the market thinks the Fed is going to tighten, the dollar appreciates against the Euro, money IS tighter.

20. March 2015 at 14:49

There’s surely some serious endogeneity problems in the first graph. Lower NGDP = lower E = higher P/E. You’re gonna need something more sophisticated, like some instrumental regression to properly disentangle the effects.

20. March 2015 at 15:04

Like this is one of those cases where it probably ISN’T a good idea to use NGDP as the dependent variable from an econometric analysis due to endogeneity (or as an independent variable due to major multicollinearity problems). So we really do need to find a really accurate instrument to determine the stance of monetary policy. What about broad money measures?

20. March 2015 at 15:27

When “patience” (meaning 2 FOMC meetings)was substituted for a more extended and open-ended “patience” the dollar depreciated significantly relative to the Euro. So, maybe the dollar reflected, in addition to looser MP in the EZ, the expectation of tightening MP in the US.

20. March 2015 at 15:57

foosion, The Economist.

Doug, That’s right.

Britonomist, NGDP is being used as the independent variable.

On the endogeniety question, I’m not denying that if you make money tight enough asset prices will fall. But that’s not the claim being made, as far as I can tell. People are claiming that bubbles are more likely to occur during periods of easy money, and that’s just not true.

20. March 2015 at 16:06

Scott, off topic, but today the Fed announced record profits for 2014:

http://money.cnn.com/2015/03/20/investing/fed-profit-balance-sheet/

Also, out of a balance sheet of $4.5 Trillion, $800 Billion will be maturing in the next two years. Sounds to me that those who are worried about the Fed being unable to unwind and being forced to sell bonds at a loss are worried about nothing.

20. March 2015 at 16:34

On the Fed’s profit and balance sheet (following NoI off topic) Of the many biases out there about Fed activity, one is about what they need to do to get “normalized”. NoI’s article mentions that they had about $850 billion in assets in 2008. That’s been so long ago, if the last 7 years had been normal, the Fed would be past $1.5 trillion, heading for $2. Even now, without looking at excess reserves, they have $1.8 trillion in liabilities. They don’t have nearly as much to unload as what our mental accounting leads us to intuit. NoI is right. There might have been duration risk at some point, but there doesn’t seem to be any at this point. They will never come close to having to sell many of those bonds.

20. March 2015 at 16:54

John Cassidy is a terrific financial writer, but monetary policy…well, he flubbed.

Still, the dollar story is fascinating…some say the dollar is overvalued. Swiss lite?

The answer? What else? Print more money.

20. March 2015 at 19:10

High inflation increases accounting earnings as depreciation is based on nominal historic cost.

Of course high NGDP growth (assuming interest rates track NGDP) also limits credit excess due to the convention of using interest/income metrics for credit qualification. But this point has been discussed here before.

21. March 2015 at 00:51

“The new information in the last year has been monetary stimulus out of Europe”

What about the other currencies that have depreciated against dollar too?

21. March 2015 at 05:35

“Not to mention that there is essentially no evidence as to what causes bubbles, which are not generally associated with easy money policies.”

There is not only copious evidence that the cause of bubbles is inflation of the money supply that enters into the loan market and lowers interest rates, but the strongest theory points to it as well.

Michael Darda is engaging in a fallacy of equivocation. When he addresses the question of whether or not “easy money” causes bubbles, then he has to actually address the definition of easy money as used by those people he is responding to.

He can’t just define easy money as what is happening to NGDP. Sure, HE can define easy money any way he wants, but he can’t claim to be saying anything to the theory that defines easy money differently.

Bubbles caused by easy money almost always take shape when the Fed is trying to reverse a deflationary recession. The bubbles do not form on the basis of any absolute height of any nominal variable deviating from some “normal” trend. Bubbles form on the basis of real activity diverging from what is physically sustainable. This is usually accompanied by nominal variables deviating not from some “normal” absolute rate, but from what would otherwise have taken place in a free market.

This is by the way a basis that not only the Fed utilizes, but what everyone who calls upon the Fed to act utilizes as well. If you ever have the idea “The Fed should print more money to avoid a recession” then what you are invariably saying is that if a free market were to determine the money supply, it would likely result in a lot less money creation at the time.

The reason why in the historical sense bubbkes busts are not correlated with NGDP is because bubbles tend to form when deflation would have otherwise resulted in declining NGDP. They tend to form at these times because that is precisely when the Fed tends to be most active.

Neither Sumner nor Darda have even addressed the argument that easy money causes bubbles. All they did was pretend that their own definition of easy money is the definition everyone uses. Solipsism much?

21. March 2015 at 05:55

Sumner: “People are claiming that bubbles are more likely to occur during periods of easy money, and that’s just not true” – but it is true. Only if you define ‘easy money’ in a tortured way, the way Sumner does, is it not true. In fact, as is well known, money is easy towards the end of a business cycle, when exuberance is high, hence bubbles form. See the book by Shiller, “Animal Spirits” for examples.

PS–on ‘sticky wages’ see: “Economists often express surprise at the small fraction of labor contracts that provide for COLAs (i.e., that include indexation). The best data on this question come from a large sample of Canadian union contracts from 1976-2000.12 Only 19% of these contracts were indexed. Furthermore, where such indexation did occur, it was far less than onefor-one: COLAs typically kicked in only after inflation had risen by more than a specified target” — from Shiller, “Animal Spirits”

21. March 2015 at 07:20

All, “bubble is defined as overvalued stocks” ? I think it is a simplistic definition. I haven’t done this research, but if I had to bet, I would bet that when the observed bubbles did burst, that would be highly correlated with tight money concurrently (in Sumner’s definition, meaning low or negative NGDP growth). Now, MF and Ray here are talking about conditions that allowed bubbles to form. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to find any statistical significance between valuation levels of whatever assets and ex-post observed bubbles. For every instance of a “stretched” valuation that actually burst as bubble, you will find a number of others that didn’t burst…

21. March 2015 at 07:46

Negation, Thanks, I did a post.

Kevin, Why do you think the base would have “normally” grown so fast?

Vaidas, Japan due to monetary stimulus, the commodity exporters due to low commodity prices. The SF has appreciated.

But I certainly agree that other factors might have been involved, as I said. It’s just that there is no new info about Fed tightening.

Ray, You think Bernanke’s definition is “tortured?” And did the 1987 stock bubble occur at the end of a business cycle?

21. March 2015 at 18:50

“Ray, You think Bernanke’s definition is “tortured?””

And why not a little appeal to authority to boot. Bernanke makes one off the cuff remark that contradicts years of statements, and we are all supposed to pretend that NGDP is now the “official” definition of easy or tight money, and not only that, but miraculously NGDP is what almost 100 years of free market economists had in mind when they talked about easy money being the cause of bubbles.

Unbelievable.

21. March 2015 at 19:50

I know I am a bit of a broken record on this, but the economic history of the C19th indicates that “bubbles” (strong fluctuations in asset prices) are perfectly compatible with “tight” money. After all, if low interest rates are indicative of money being a relatively good asset (so a good “risk ballast”) and of savings “pushing on” investments, why would not asset prices surge?

Add in technological uncertainty (which the C19th had lots of)–including geographical uncertainty (which places will be the centres of which new industries: which the C19th also had lots of)–and you are away.

BTW, new financial instruments could also operate as “new technology”. While regulatory blocks on asset supply (such as in Zoned Zone housing markets) would tend to increase the amplitude of effects.

As an aside, lots of low risk government debt would be a good “risk ballast” too. See UK in the C19th, US after 1945.

(By “risk ballast”, I mean assuming that people have a certain average risk preference, then plentiful low risk assets would make folk more willing to balance out their asset portfolios with higher risk assets, such as new technology stocks. Noting that the C19th asset boom-and-bust history starts with the various “railway manias” at a time when UK public debt was over 200% of GDP, having peaked at around 260% of GDP.)

21. March 2015 at 19:52

Also, surely “animal spirits” are just how folk are currently reading uncertainty.

22. March 2015 at 06:14

Lorenzo, Good points.

22. March 2015 at 11:15

Bad politics rule. FDIC insurance fees should be applied to the FBOs. But the dollar’s rise is coterminous with Yellen’s tightening. And any “flight-to-safety” contracts the E-D market (forcing a conversion penalty). Then the prospect of domestic output rising faster than our trading partner’s doesn’t help.

The solution is simply to get the CBs out of the savings business, then the unregulated E-D market is put at a dis-advantage.

I.e., all domestic time/savings deposits are the indirect consequence of prior bank credit creation. The source of TDs is other bank deposits, directly or indirectly via the currency route or thru the CB’s undivided profits accounts.

Voluntary savings are not a source of loan-funds to the CB system. Their growth does not per se add to the “footings” of the consolidated balance sheet for the system. Their growth has no effect on the size or gross earnings of the banking system, except as their growth affects are transmitted through monetary policy.