The “new claims” puzzle

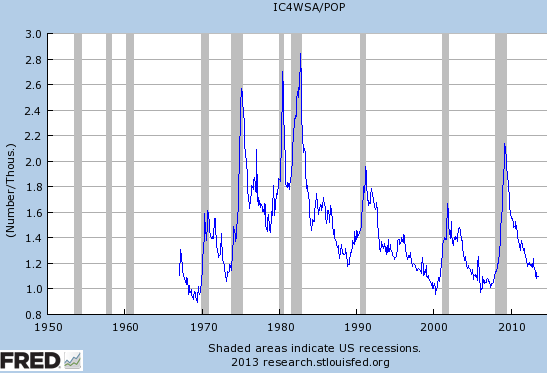

The new claims for unemployment this week was a shockingly low 320,000, bringing the 4 week average down to 332,000 335,000, which is the lowest since October 2007. This graph shows the ratio of the 4 weeks average to US population (times 1000 to make it easier to read.)

The most recent week on the graph is at about 1.1, but today’s figures are at 1.049 1.058, if they were added. This means the ratio of new claims to pop is roughly back to the boom levels of 1999-2000 and 2006-07. And yet the other indicators (total jobs, unemployment rate, etc), remain deeply depressed. I can think of two ways to interpret this data:

1. Casey Mulligan is right, we have lots of structural issues that are causing high unemployment right now. The job market’s not that bad, it’s just that lots of people don’t want to work at the wages being offered, or are frozen out by the 40% rise in minimum wages during the housing bust.

2. AD is still the main problem, but since 1975 there’s been a long term downward trend in the claims/pop ratio, for some mysterious reason. That trend would explain why (according to new claims) the labor market looked as good in 2006 as 2000, even though most people think it was not.

In the past I’ve argued that the minimum wage and extended UI benefits probably raised the natural rate by 0.5% to 1.0% at most. I’m sticking with that for now, although I do believe today’s data makes the structural hypothesis a tad more likely. What would it take for me to change my mind? If wage growth stays around 2% (or more) and NGDP growth stays around 4% (or more) and the unemployment rate stops falling for a couple years. Then I’d agree Mulligan is right about the current labor market. Of course unemployment has already fallen from 10% to 7.4%, so it’s almost certain we’ve have above natural rate unemployment over the past few years. And I still believe it will fall further.

Of course there are lots of other puzzles, like the low labor force participation rate.

Tags:

15. August 2013 at 07:36

Some people have lost the transportation which allowed them to continue the job search, and I remember stories of municipalities cutting back on bus services as well – both of which are needed to claim unemployment.

15. August 2013 at 07:36

Prof. Sumner,

Thank you very much for covering this!

By the way, another pessimistic analysis of the future growth potential of the U.S. economy is getting a lot of attention:

http://www.aei-ideas.org/2013/08/why-wall-street-thinks-the-us-future-isnt-what-it-used-to-be

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/08/14/why-america-needs-to-get-used-to-slower-growth

15. August 2013 at 07:40

I suspect if you looked at the civilian labor force rather than the total population the ratio would be even more extreme given what has happened to the LFPR.

15. August 2013 at 07:51

And by the way, there’s a big new book attacking Friedman and neoliberalism that unfortunately seems to be getting a lot more attention than Daniel Stedman Jones’s book.

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2013/08/fixing-old-markets-with-new-markets-the-origins-and-practice-of-neoliberalism.html

http://www.nextnewdeal.net/rortybomb/mirowski-vacuum-and-obscurity-current-economics

15. August 2013 at 08:35

First off, too much welfare.

Second,

I think this gets right back to my thing about Roger Farmer (he runs UCLA Econ), pls read this and tell me what you think?

http://www.voxeu.org/article/does-fiscal-policy-matter-there-better-way-reduce-unemployment

Animal Spirits are too low. So we have exactly the unemployment we’re supposed to have.

15. August 2013 at 08:38

TravisV,

‘Attack’ is the right word. As far as I know, Philip Mirowski has never offered an original argument against “neoliberalism” or successfully described the views of anyone he calls a neoliberal. In fact, his writings are conspicious by their lack of arguments.

That’s why his reputation as a critic of neoliberalism and “neoclassical economics” confuses me. Lot’s of people argue against these things, so how can someone who doesn’t do that become known as a notable critic? It would be as if Igor Shafaerevich was a more well-known critic of socialism than Hayek or Karl Popper.

Is Bulverism so powerful that one can literally make a respected academic career out of doing it?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulverism

15. August 2013 at 08:50

W. Peden,

Great points. As I read the Naked Capitalism link above, I kept thinking “What’s Mirowski’s big alternative?” And he never provided one. Does he have one? Does Konczal have one?

If you read below, you’ll see Yglesias observe that no one really does.

http://thinkprogress.org/yglesias/2011/07/18/272099/what-is-the-alternative-to-neoliberalism

15. August 2013 at 08:51

320k initial claims is not “shockingly low.”

350k is generally thought to be the level between an increasing rate of unemployment and a decreasing rate of unemployment.

335k for the 4 week average suggest a monthly job creation of 180k — (vs 155 k the last 3 months)

Other indicators of job creation are not deeply depressed.

NPF shows 2M + jobs created in the last year.

Household survey gives similar numbers.

We have seen 34 months of consecutive job growth.

The data is entirely consistent. Job growth is happening, has been happening, not as fast as some might like, but neither is it horrible. We did not get a sharp rebound coming out of the recession as some had hoped, but that wasn’t my forecast, and I would have been surprised if we had “snapped back.”

15. August 2013 at 09:03

Scott, government employment peaked in May 2010 at 23 million (census workers, stimulus, thos these are seasonally adjusted too) and is now 1.14 million lower.

This is historic- only the second time since WWII that employment by Leviathan has contracted (early 1980s.)

In that time, private employment has grown by almost 7 million.

To me, this is all good, although shrinking government has been a drag on overall employment growth.

And while I think I buy that RGDP might be 5% higher if you were running the zoo, it strikes me that this would be a mixed blessing in terms of getting a headlock on Leviathan.

What did Rahm Emanuel say? Don’t let a crisis go to waste?

15. August 2013 at 09:06

By the way, this is an excellent Peter Schiff debate everyone should watch:

http://blog.supplysideliberal.com/post/58305230102/miles-and-mike-konczal-vs-peter-schiff-on-huffpost

No, Konczal doesn’t do as well as Prof. Sumner. However he had less time available and he still did a decent job. I’m amazed that he’s so good on this subject and so bad with the Mirowski interview, etc.

My two critiques: first, there was a lot of repetition of “if we have more inflation, that means we’ll make more valuable stuff.” That’s well and good but employment should be mentioned before that. “If we have more inflation, that means EVERYONE WILL BE EMPLOYED. And we’ll also make more valuable stuff, which is icing on the cake.

Second, I kinda get Kimball’s point about negative interest rates. However, I think he should have talked about sticky wages first before talking about negative rates.

15. August 2013 at 09:08

Travis, Thanks for the links.

Morgan, Why should I look at those links? Summarize please.

Doug, The ratio of claims to population is far lower than the mid-1990s, when the labor market was much stronger. Don’t use raw figures for comparison. Use ratios.

15. August 2013 at 09:11

Re: slower growth. Economic models predicated on 3% growth that fall apart when the target is not achieved strike me as having a soft, chewy Ponzi-ish center.

15. August 2013 at 09:19

TravisV,

It’s not even a question of having an alternative: it’s a matter of having an argument.

Karl Marx, Harold Laski, J. K. Galbraith, Noam Chomsky- all of them may lack any sound arguments against capitalism, but they certainly provided a lot of arguments, many of them very good and thought-provoking. One can make a case that responses to Marxism from economists like Mises, Hayek and Bohm-Bawerk were very important in furthering our understanding of how the world works.

In contrast, describing capitalist thinkers in a disparaging and inaccurate way isn’t an argument, it’s a description, and saying that “X is wrong about Y because X believes Y due to X being Z” is a textbook logical fallacy. It’s frustrating, because other than saying what I’ve said, there is literally no relevant response one can make to Mirowski’s work other than history and historical questions are distinct from economic/moral questions.

Even if one were to somehow show, line-by-line, that everything Mirowski has written is factually incorrect, one would have contributed nothing to economics or philosophy, and no defence of the theories he attacks. So what’s a philosopher supposed to do, other than write about something else? And yet then Mirowski becomes known as a notable critic of neoliberalism, as opposed to a historian?

15. August 2013 at 10:08

Funny thing about ratios…

Non-farm payrolls, and initial claims have been stubborn in the their ranges since 1980.

The peak in unemployment claims in ’09 was lower than the peak in claims in ’81 despite a population and labor force that is 50% larger. The trough in initial claims in ’06 is at the same level as the trough in claims in ’88.

monthly NFP peaked out at about the same levels in ’98 as it did in ’88. The 2006 peak was lower, and we are in a similar range of hiring as we were in the mid-naugties.

15. August 2013 at 10:12

Prof. Sumner, to the extent that UI and other such programs cause structural unemployment, how much of it do you think comes from the desire not to work vs the disincentive effect of extremely high net marginal tax rate on the working poor? I know this isn’t your area of expertise but I’m genuinely curious where you stand.

15. August 2013 at 10:27

Christ.

Dude, it’s an economist at UCLA, you are an economist.

He makes what to me is an original argument. The last time I found a new interesting argument like this… was yours.

Here’s what is interesting:

1 The standard New-Keynesian and real business cycle models (Woodford 2003, Kydland and Prescott 1982) both contain a unique steady-state employment rate that is pinned down by fundamentals. Neither model contains unemployment and therefore cannot explain why unemployment has doubled in the current crisis. Gertler and Trigari (2009) and Hall (2011), have introduced unemployment into an otherwise standard macro model but they cling to the assumption that there is a unique natural rate of unemployment, explained solely by fundamentals. Models that maintain this assumption cannot credibly explain financial crises.

2 Farmer’s (2009, 2010a, 2010b, 2010c, 2011) model interprets Keynes’ General Theory (1936) in an original way. It reintroduces the idea, absent from new-Keynesian economics, that there is a continuum of steady-state unemployment rates. Farmer’s framework provides an independent role for business and consumer confidence. Confidence is treated as a fundamental that selects an equilibrium.

15. August 2013 at 11:00

The 4 week moving average was actually a little lower at 332,000 and that was the lowest since November of 2007. The October date is for the headline initial claims data of 320,000.

Not that those numbers change anything but just for clarification.

15. August 2013 at 11:27

Brian, Yup.

Doug, That’s much better.

rbl. Both, I think most people (including myself) would rather play than work. But that alone doesn’t cause much unemployment, as few people can survive without working.

Morgan, I’m afraid those quotes don’t get me as excited as you seem to be. Why can’t natural rate models explain unemployment?

15. August 2013 at 12:18

According to two Cleveland Fed economists, small business is underperforming;

http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/commentary/2013/2013-10.cfm

———-quote———

If small businesses have been unable to access the credit they need, they may be underperforming, slowing economic growth and employment.

Different views have emerged about the cause of the slowdown. Bankers say the problem rests with small business owners and regulators””business owners for cutting back on loan applications amid soft demand for their products and services, and regulators for compelling the banks to tighten lending standards (which cuts the number of creditworthy small business owners). Small business owners, in turn, say the problem rests with bankers and regulators””bankers for increasing collateral requirements and reducing their focus on small business credit markets, and regulators for making loans more difficult to get.

In our analysis, we find support for all of these views. Fewer small businesses are interested in borrowing than in years past, and at the same time, small business financials have remained weak, depressing small business loan approval rates. In addition, collateral values have stayed low, as real estate prices have declined, limiting the amount that small business owners can borrow.

Furthermore, increased regulatory scrutiny has caused banks to boost lending standards, lowering the fraction of creditworthy borrowers. Finally, shifts in the banking industry have had an impact. Bank consolidation has reduced the number of banks focused on the small business sector, and small business lending has become relatively less profitable than other types of lending, reducing bankers’ interest in the small business credit market.

———–endquote——–

15. August 2013 at 13:11

Natural rate doubts:

http://www.rogerfarmer.com/NewWeb/PdfFiles/natureal%20rate%20doubts.pdf

He uses a bunch of symbols, which I know isn’t your thing.

—-

Are you screwing with me?

I’m just going to call the guy and put him on the phone with you.

I trust my nose for new arguments, and rather than telling me you don’t get excited….

I smell something here that accepts old keynes, but focuses on the parts of him, nobody likes to remember, and uses his arguments to say the government shouldn’t be doing anything that makes the private sector less confident

So I suspect, there’s probably some low hanging fruit others haven’t gotten into.

But IF this is stuff thats already part of econ, and well part of literature, then maybe it’s not interesting.

But if it’s not been thoroughly vetted and discarded, it is definitely interesting.

15. August 2013 at 13:22

Yeah he’s definitely keying off Diamond’s Coconut thing, saying sometimes markets don’t clear…

Then says when not clearing, government job is to get animal spirits moving, and that that DOES NOT happen by the government running the economy.

As such, we have the amount of unemployment structurally, the lever is how much the government is getting in the way…

Sure if there is a government policy EVERYBODY thinks is worth while do it, but if in general lots of guys like me HATE it, well then, unemployment is the result.

Using Keynes to put the entrepreneurs at the top of the heap will give Krugman migraines.

Just read the damn thing.

15. August 2013 at 13:29

Morgan Wartsler,

“The conventional explanation for the buildup of inflation in the 1970s is that the Fed reacted to an increase in the natural rate of unemployment by conducting an overly passive monetary policy. We show that this explanation is difficult to reconcile with the observed comovement of the Fed funds rate and inflation.”

We’ve seen a lot of the “low interest rates imply loose money” resaoning recently. It’s sad to see that the converse mistake hasn’t yet died. That’s assuming that they reason on the basis that the upward trend in the FFR prior to 1982 means that monetary policy wasn’t overly passive; like you, Morgan, it didn’t take too long for them to go too far beyond my grasp of mathematical economics such that I could easily follow what they were saying.

15. August 2013 at 14:08

Scott,

I have 2 admittedly long & rambling posts about this:

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2013/07/demographic-distortions-in-unemployment.html

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2013/08/unemployment-duration.html

I estimate that without MW, emergency UEI, and demographic factors, we’d be crossing below 6% UE by now, near a new, higher base UER. A lot of this is hard for me to summarize, because the phenomenon is a kind of hybrid of demographic and cyclical issues. But, here are a few thoughts & factoids:

regarding MW:

While the absolute total size of the labor force has increased since 2006/2007, hourly workers declined by 3.6 million, and 1.7 million of those were teens.

The 40% increase in MW means the MW workforce increased from 1.7 to 4.4 million. In addition to this, some portion of those 3.6 million former hourly labor force participants were effected by the MW increase. Broad historical correlations would predict about a 1 million increase in UE from this. Considering the scale of the other numbers, this seems reasonable. My estimates suggest that, of the effected workers whose wages would have been below the new floor, only 13% would need to be counted as unemployed to get 1 million new UE. Of course, the number will slowly decline over time, as long as we don’t raise MW again.

regarding EUI and demographics:

As a % of LF, UE durations under 27 weeks have been flat for more than a year at about 4.8%, about 1% higher than the flatline levels of previous recoveries. UE durations of 27+ weeks of workers not on EUI have flatlined at 1.6% of the labor force, which is also 1% higher than earlier recoveries. All of the declines in UE since early 2012 have been from decreases in the EUI numbers.

The GAO surveyed workers who had used up their emergency UEI. Of those who were still not employed, more were on SSI benefits than SNAP benefits.

The number of workers over 55 with UE duration over 26 weeks peaked at a little over 1.1 million and is still at 800,000. For the 65+ age group, it’s still at 200,000, the same level as late 2009.

Workers younger than 45 with less than HS education have average UE duration of 28 weeks. This increases systematically as age & education increase. 45+ year olds with at least some college have UE duration of 36 weeks. Married workers also have higher UE duration than unmarried workers. Clearly, older, more educated, married workers have more ability for consumption smoothing.

The LFP of workers over 55 declined until the mid-90’s when it started climbing again. Until the 1960’s, UER for this age group basically followed the same pattern as other age groups, suggesting that in that era, older workers had the same income needs and work patterns as other age groups. From the 1970’s to the 1990’s, the UER for older workers stayed at a much lower level than younger groups. The combination of low LFP and low UER suggests that retirement was the overriding factor. Since the 1990’s UER for older workers has come back up, and in the current cycle, is more persistent than for younger age groups. I think that this reflects the new era where extended retirement and longer lifespans have led baby boomers to retain a partial connection to the labor force, which includes an unprecedented level of discretion.

15. August 2013 at 14:27

Claims are a high frequency leading indicator that suggest a step-up in job creation and income growth ahead. By the way, that’s also what rising long rates and a steepening yield curve are signaling. Yes, stocks were down today, but YTD rates and stocks are both up a lot. Maybe the Wicksellian rate is finally rallying and the taper won’t be so bad…..

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=luR

15. August 2013 at 14:51

Scott, might I suggest that the trend may have something to do with this:

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/03/disability-insurance-americas-124-billion-secret-welfare-program/274302/

That’s a HUGE increase. Probably several reasons, all explain a part of it:

1) aging population

2) increase in claims due to systemic abuse

3) recession induced people to use system as alternative to UI

4) increase in chronic disease burden

15. August 2013 at 15:09

I have a pretty clear idea of what I think the data are telling us. A lot of people have been out of work (not necessarily “unemployed” in the official U-3 sense, but maybe in a U-5 or broader sense) for long periods of time. Employers are reluctant to hire such people, for a number of reasons, some of which reflect a clear decline in aggregate supply (e.g. people’s skills have deteriorated) and others don’t (e.g. long-term unemployment status is a very noisy signal of low worker quality, but still better, from an employer’s point of view, than no signal at all, or the very expensive signal generated from an intensive selection process — so even rational employers still pass up many good applicants). The unemployment rate is high because there are all these long-term unemployed people whom employers don’t want to hire.

At the same time, turnover is low. (Note that the hiring rate in the JOLTS statistics is still quite low, even as initial claims are also low, so basically employers are standing pat, not doing much hiring or termination.) Indeed, turnover (based on a variety of statistics, because we don’t have explicit aggregate turnover data for the whole period) appears to have been trending downward for about 25 years now, so it’s not surprising that it’s quite low today.

Now labor demand overall (as indicated, for example, by the job openings statistics) is fairly weak, but not extremely weak, and since turnover is so low, even fairly weak labor demand is still strong enough to generate very low initial claims.

Is our problem therefore cyclical or structural? Obviously there’s some of both, but the situation is complicated. Overall labor demand, as I said, is fairly weak, so some of our unemployment is cyclical. Low turnover reduces structural unemployment; deteriorating skills raise structural unemployment; so maybe these two roughly cancel out. But what are we to make of other reasons for not hiring the long-term out-of-work? It’s hard to say. I think there’s a strong case to be made that employers are going to need to be “bribed” (in the form of a slightly overheating economy) to hire these people. So in that sense structural unemployment has become a bigger problem.

On the other hand, I think there is a lot of what you might call “pent-up wage restraint.” After equilibrium real wages fell, nominal wages continued rising because of inertia, but now the inertia has shifted. As equilibrium real wages start to rise more quickly, there’s going to be a period of catch-up during which nominal wages, which people now expect to rise at about 2%/year or less, still rise very slowly. So there’s going to be some room for “non-inflationary overheating.” So there may be a chance to reduce structural unemployment (or you might say, eliminate unemployment that is short-term structural but long-term cyclical) without causing higher inflation.

15. August 2013 at 16:22

What mystery? Aggregate demand is weak, but unemployment benefits running out.

15. August 2013 at 16:28

If our persistently high unemployment for the last five years was largely structural, then we would be seeing much more wage inflation. Additionally, the data would show that there are more job openings, in some industries, than unemployed people. This is not the case.

Or you can believe in the nonsense that unemployment insurance, food stamps, and minimum wage are the primarily causes of our unemployment problem rather than a lack of demand.

While there are some structural components causing the decline in the LFPR, there is a large cyclical component. People are dropping out of the labor force do to a poor labor market. The decline is coming from younger people. The LFPR has actually increased for people 55 and over.

15. August 2013 at 16:29

“If wage growth stays around 2% (or more) and NGDP growth stays around 4% (or more) and the unemployment rate stops falling for a couple years. Then I’d agree Mulligan is right about the current labor market.”

This isn’t very rigorous. Seems arbitrary.

15. August 2013 at 17:09

Antiderivative said:

” People are dropping out of the labor force do to a poor labor market. The decline is coming from younger people.”

In news totally unrelated to your comment….In 2006, 5% of workers 25 & under were at minimum wage ($5.15). Now that it’s $7.25, 12% of them are at minimum wage (down from 15%). The 16-24 labor force is down 10% from 2006.

For workers over 24, of whom only 1.4% worked at the minimum wage, LF is up over that time.

LFPR is up for people 55 and over. But, the LFPR for 60 year olds today is lower than the LFPR for 55 year olds was 5 years ago. The baby boomers are working more than their predecessors, but they are aging. It’s the aging that is the factor pulling down the LFPR.

15. August 2013 at 17:36

It could just be noise in the dataset. Either way, the main problem is Congress. How can we have real, genuine growth from entrepreneurs in a world where no one knows what taxes and regulations are gonna be? Why would entrepreneurs invest and take risks in a world where regulations and rules favor the big boys? The answer is that they won’t.

15. August 2013 at 17:36

Continuing our discussion on a newer post as you requested.

In reference to the HPE when the Fed is injecting reserves at the zero bound via an overnight reverse repo trade, you wrote:

“The public tries to get rid of these excess cash balances.”

Sorry but why? These cash balances exactly offset the repo on the “injectee’s” balance sheet.

Prior to the injection, the injectee had:

+1 Treasury Bond

After the injection, he has:

+1 Treasury Bond (still owns all the economics of the bond despite having pledged it as collateral to the Fed)

+1 US Dollar Cash Balance (A)

-1 Overnight Repo Agreement with Fed (B)

Both (A) and (B) have an NPV of par, always.

Both (A) and (B) pay/receive 0% interest (rounding down measly IOR and repo rates).

Granted (B) cannot be used as a means of payment but the injectee could already have sourced cash against his Treasury bond at 0% anyway since we already were at the zero bound yesterday (i.e. he had the option to execute that exact trade with someone else at the same rate if he wanted to make a payment)

So why? Why would “the public [try] to get rid of these excess cash balances.” ? What did the Fed do that changed anyone’s predicament?

15. August 2013 at 18:20

In reverse order . . .

DOB, I was assuming interest rates are positive. If they are zero then there is not much HPE (depends if they are perfect substitutes.) Pretty much all discussion of the HPE is predicated on positive interest rates or expectations that rates will be positive at some date in the future.

Suvy, I don’t think Congress controls NGDP.

Everyone, I think it’s useful to first think about the path of NGDP since 2007, and imagine what sort of changes you would have expected if that’s all you knew. Here’s my view:

1. The unemployment rate is roughly what I would have suggested from the path of NGDP. This implies it’s all demand side.

2. The total number of jobs is less than I would have expected, this implies it’s partly structural.

3. The claims numbers have fallen faster than I would have expected. I’m not sure what that means, but I find Andy’s discussion as plausible as any other I’ve seen.

Statsguy, I think the disability increase helps explain the total jobs doing worse than the unemployment rate.

Kebko, I find that plausible on the minimum wage. Very early in the recession I noticed something weird going on with the younger workers—different from the 1982 recession which had higher overall unemployment.

Tommy, let’s hope so.

Morgan, Has anyone ever insisted you date a certain lady? How’d that work out?

I’ll refuse to take a call from him, just to screw around with you even more. 🙂

Seriously. When I move out to LA in a few years I’ll try to meet him sometime.

15. August 2013 at 18:26

Scott,

To clarify, when I say zero bound, I always mean the short end. I’m assuming long term interest rates are positive.

As long as there is a zero bound (hopefully we blast it in the near future), long term interest rates are going to be strictly positive since they’re a effectively a call option)

So in that context, why would the injection depicted above have any effect?

15. August 2013 at 19:32

How can it be that job oppenings are in a continuous upward trend for quite some time and yet hirings are at the same level as they were in 2010? Can’t this be seen as sign that cyclical unemployment is actually becoming, slowly and possibly only partially, structural, given the skills’ mismatch?

In my view, it is simply too much adding to the evidence of structural issues.

15. August 2013 at 21:43

Scott,

I think the EUI and demographic factors are a lot bigger deal than the MW factor. There are many millions of 55+ year olds with personal ties to a 35 year career, and they are looking at 30-40 years of life expectancy.

Now, some guy takes an early retirement deal from his employer after talking to a couple associates about doing some part time or consulting work in a few years, just to keep busy and keep in touch with old associates. The recession takes a little longer to recover than he thought, so he’s not doing as much consulting as he’d planned. He’d like to earn a few bucks, but the kids are gone and the house is paid off. He’s on the board of directors at his church, and he’s coaching his grandsons little league team, and he’s gotten involved in local politics, when he’s not out of town in his RV.

A census worker calls him up. “What’s your employment status?”

You call that guy up five months in a row, he’s going to give you 5 different answers.

We’ve got millions of workers in a demographic situation that has never been significant before. The odd thing is that I think this factor is pro-cyclical, but in a way that kind of slows down and mitigates the business cycle because mostly its a new level of consumption smoothing connected to a flexible, opportunistic labor pool.

16. August 2013 at 04:14

Scott – I’d say the path of RGDP and NGDP since the recovery began suggest a much slower pace of annual job gains and a much more gradual fall in the unemployment rate than what we’ve seen:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=lvT

Indeed, job gains over the last year are consistent with about 3% RGDP growth; the 0.8 percentage point fall in the unemployment rate over the last year is consistent with 4-5% RGDP growth.

Thus, one would have to conclude that either 1) we are systematically under-estimating/reporting NGDP and hence RGDP growth; or 2) productivity has slowed/structural impediments have reduced the labor force in a way that allows only modest GDP to pull unemployment down at a relatively fast clip. Perhaps some combination of both…

16. August 2013 at 04:36

[…] The new jobless claims puzzle – Money Illusion The really bad news behind the jobless claims drop – Net Net U.S. […]

16. August 2013 at 06:45

Tommy Dorsett:

What would you see in real GDP and UER if you had a labor force that, for secular demographic reasons, had been increasing by .3% a year for 35 years and now was decreasing by .3% a year?

16. August 2013 at 07:06

“Morgan, Has anyone ever insisted you date a certain lady? How’d that work out?”

No. My friends wouldn’t do that to anyone. But I’ve intro’d three married couples.

What you do all day is read blog posts etc from economists making arguments.

I’d like you take at minimum if Farmer’s right about Keynes GT.

16. August 2013 at 07:09

DOB, Because it would create an expected future HPE. People expect the zero bound to eventually end, and then prices will rise. That expectation causes prices to rise today.

apt, There are structural issues, the question is what proportion of unemployment is structural?

kebko, Very good point.

Tommy, My best guess is that productivity has slowed. But as you know I believe monetary policymakers should pay no attention to RGDP anyway.

16. August 2013 at 08:15

Another explanation that I don’t see mentioned is the growth of the underground economy. There is a pretty large incentive not to report income (or hide most of it) from those that could be eligible for medicare, food stamps and other government benefits and Disability insurance(like previously mentioned). The Internet has made it much easier to find ways to make money. The recession introduced many people to this and they are not returning to minimum wage jobs with no benefits.

16. August 2013 at 08:45

Scott,

“Because it would create an expected future HPE. People expect the zero bound to eventually end, and then prices will rise. That expectation causes prices to rise today.”

Why wouldn’t the public realize that all of the excess cash will be drained the minute the Fed wants to target a positive nominal interest rate? Is HPE contingent on the public being irrational?

16. August 2013 at 10:27

Scott,

you have me thinking about something…

In the same report as Initial clams is a report for continuing claims.

The ratio of initial claims to continuing claims has been changing over time. In the 70s and 80s there there was one new claimant for ever 6 continuing claimant. Currently the ration is 9:1. The change in this ratio is not just in the last recession. It has been creeping this way for 20 years.

What does this suggest?

It suggest that those who are loose their job are out of work 50% longer.

So, back to the low level of initial claims…. not very many people are getting laid of and not very many people are getting hired either. It suggest an economy that is less dynamic, less churn, less creative destruction than earlier eras.

16. August 2013 at 11:38

Hate to rain on your parade Morgan but there is an FT article, can’t find at the moment, where Farmer thinks the government should set a ceiling and a floor on the stock market in order to calm those wild spirits. The spirits argument is so easy to manipulate one could say, “Don’t scare them” while the other would say, “Control them”. Sounds like intervention to me.

16. August 2013 at 11:47

Nevermind, here’s the link Morgan. Badabing.

http://www.rogerfarmer.com/NewWeb/PdfFiles/Farmer_Roger_Carnegie.pdf

Page 570, 3rd paragraph from the bottom. Model looks interesting though.

16. August 2013 at 13:07

Too late for you to read this but … Looking at the stock market this week the jobs news was taken badly, a de facto monetary tightening following the Fed rule on tapering if unemployment falls. But if it was genuinely good economic news I think the optimism generated would have outweighed the Fed tightening fears.

16. August 2013 at 13:25

Daniel,

I’m suggesting Farmer would likely be comfy with NGDPLT instead of S&PLT.

I think this bc he spends a bunch of time essentially lamenting the random walk of market participants all guessing about future NGDP.

Also, Farmer is fine with Rational Expectations, he just tries to deal with the “belief function” of future NGDP.

I see no reason why he’d fight getting NGDPLT locked in – I think he’d cheer it.

Meanwhile, Scott, I believe has said Ben’s targeting the stock market.

Moreover, if we target 4.5% NGDPLT, both Scott and Farmer would grant that unemployment could stay high.

Personally, I think confidence / animal spirits matter. You can get MP all tucked away on auto-pilot, but you still have to worry that the market participants

Which is why I don’t “think” that Scott isn’t wedded to natural rate hypo. I don’t see what it gets MM.

I especially like using Old Keynsianism to argue Private Sector needs more freedom. I think it sneaks up behind Krugman and he gets even sloppier.

I don’t know why Farmer thinks drops is Wealth matter more than Income…

But I suspect it’s bc it scares the private sector winners… the capital goes into lock down, and you can’t really scare it with MP.

And I REALLY like the Farmer’s search function, as it goes well with GI CYB.

Also, I believe firms have a belief on wages and prices and they don’t budge off those in a global market.

There are new machines that compete with Chinas manufacturing – but you can only make it work if the guys running them earn $12 per hour.

You can’t find folks who know how to run new machine that will work for $12.

I see this kind of reasoning amongst associates everyday.

The price point you can ask, you know it, you know your other costs, so it only works below a certain wage.

16. August 2013 at 15:16

I’ve never understood the mindset of the Economists who look at the unemployment number (however measured) and declare victory. I know far too many people with degrees working menial jobs to operate under any illusion that the labor market has recovered.

Even if you grant that these people lacked the foresight to choice the right degree in the booming fields of… err, whatever is hiring, the people who make the structural arguments tend to be the kind of people who end up arguing that there’s nothing to be done, so we’d better just write people off.

That may not be the intent, but that certainly seems to be the policy implication.

At any rate, I don’t find the structural argument very satisfying. If the higher minimum wage where impacting employment, then low-wage retail jobs shouldn’t be as dominant in the recovery. It just seems like the same kind of reasoning that would lead you to advocate raising interest rates during a period of weak growth to encourage savings, so consumption increases at a faster rate.

16. August 2013 at 16:06

I combined trend LFP with census forecasts to create a LFP rate forecast, purely based on aging population.

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2013/08/its-all-demographics-again.html

16. August 2013 at 16:48

MikeF, I agree that that’s an important factor. I don’t know how big, but eBay alone provides jobs for lots of people. Often they don’t earn much, however.

DOB, No, it’s based on them being rational. If all the money is drained then how can you get NGDP growth? I’d suggest looking at Krugman’s 1998 work on Japan, especially the importance of setting an inflation target (I would prefer NGDP, of course.) Setting a target is logically equivalent to promising to keep enough base money in circulation forever to hit the target via the HPE.

Doug, Yes, they are unemployed for longer, that’s partly because they keep extending the UI program for longer and longer.

James, Good point. Here’s how I look at it. There is actual growth, there are more or less effective indicators of growth, and then there are indicators the Fed puts a lot of weight on. Let’s say both employment and output provide useful information, but the Fed only looks at employment. Then if the weekly jobs numbers suggest a strong employment report for August is on the way, the markets will expect tapering. But if there is strong output but weak employment the Fed will not taper. So markets would like strong output numbers but weak employment numbers. In other words, they’d like the economy to be strong, but they’d like the Fed to think it’s weak. We might now have the opposite, the jobs numbers look strong and the output numbers look weak. But the Fed brushes off the weak output numbers.

Thanks Kebko.

16. August 2013 at 17:41

DOB,

“No, it’s based on them being rational.”

I’ve been studying and thinking about monetary policy intensively over the past 5 years. I certainly don’t claim to be an expert, but certainly think I know more than the average joe, and an increase in base at the zero bound gives me, personally, zero incentive to spend or contribute to NGDP in any way. Of course I could just be an idiot but that would be hard for me to evaluate..

Interestingly, average joe gets pounded by the conservatives’ scaremongering over “money printing”. Evidently, he’s not doing much to protect himself from it (otherwise NGDP would be higher). That’s an interesting paradox.

“If all the money is drained then how can you get NGDP growth?”

Commit to keeping interest rates at 0% until NGDP forecast hits path. Or better yet, introduce negative nominal rates.

“I’d suggest looking at Krugman’s 1998 work on Japan, especially the importance of setting an inflation target (I would prefer NGDP, of course.)”

I agree that setting a target is essential. And I agree with you that NGDPLT (or related aggregate wage metrics) is best. You’ll get no argument from me there.

“Setting a target is logically equivalent to promising to keep enough base money in circulation forever to hit the target via the HPE.”

I specifically asked you earlier if the Fed committed to an NGDPLT path, would you still use QE at the zero bound. You said yes: “On your question, I’d do QE so that there was less unemployment (compared to waiting, which might never work.)”.

16. August 2013 at 17:43

DOB,should have of course been:

Scott,

16. August 2013 at 22:01

DOB, You said;

“Commit to keeping interest rates at 0% until NGDP forecast hits path. Or better yet, introduce negative nominal rates.”

Sure, they can commit to a low interest rate until the NGDP path is hit, or they can commit to a low exchange rate until the NGDP path is hit, or they can commit to a high gold price until the NGDP path is hit. But whatever the plan, you need to increase the base (in the long run) to make it happen. Yes, you could also decrease base demand through lower IOR. But I view those as two sides of the same coin. Both a lower base demand and a higher base supply raise prices via the HPE.

You said;

“I specifically asked you earlier if the Fed committed to an NGDPLT path, would you still use QE at the zero bound.”

I don’t recall exactly, but I thought you asked what I’d do if they committed to a NGDP path, but nominal rates were still zero, and hence it was expected to take many years to get there. I argued that in that case they should do QE to speed up the process. Or else raise the target. I’d actually prefer a higher target.

I think people make a huge mistake of thinking of QE is a lever. The goal should be to, make the base endogenous. You do whatever it takes to get NGDP expectations up to target, then you supply the amount of base money the public wants to hold at that level of expected NGDP growth. I can’t imagine a case where the public would want to hold an amount of base money greater than the national debt, if NGDP growth was expected to be 5%. But if I am wrong, the government would have to make a decision:

1. Be willing to buy riskier assets. (Or go negative IOR)

2. Set a higher NGDP target.

I don’t focus on those cases in this blog, because I focus on what I think are actual, real world, plausible scenarios.

16. August 2013 at 23:18

Agreed. Not sure what sort of “trap” you’d call it but it certainly sounds like one. In relation to our new UK monetary policy with the high unemployment rate threshold, I called it a “circular reference” like you get using a spreadsheet.

It could really tightly bound the economy, although that would be a pretty major feat to achieve. I suppose that the main danger is ever lower wage growth, and an economy constantly in danger from negative demand shocks and zero flexibility to cope, apart from “heroic” superhero central bankers. Just have to hope they never have a “bad day at the office”” or are on holiday or pursuing some other, maybe political, agenda at the time.

17. August 2013 at 00:17

The bond market is less clear what to do with the nearer prospect of tapering. It wants to sell off, as the liquidity effect kicks in. And did sell off sharply on Thursday morning. But then it rallied, perhaps thinking that tapering was bad for the real economy. Before falling again on Friday, so yields ended sharply up over the two days. Mmm.

17. August 2013 at 19:20

Scott,

It’s interesting that every time we zoom in on monetary mechanics, I can’t put my finger on anything we disagree on. Yet when we zoom out, we reach very different conclusion on the effectiveness of QE. Seems to me that it’s because you look at everything in terms of quantity while I look at everything in terms of interest rates.

I have issues with the way you think CBs can/should target fx rates (or commodity prices) sustainably without using interest rates, but probably best to not add another layer to the debate.

“The goal should be to, make the base endogenous.”

What do you mean by this? I think the base should be fixed as a fixed fraction of NGDP (lock velocity) and let the targetting be done with IOR and the overnight repo rate. There’s no reason why we need more of the medium of exchange in a deflationary environment than in an inflationary one if NGDP is going to be stable: roughly the same amount of transactions are going to be carried out. The quantity of base money is roughly controlled by the spread between fedfunds and IOR, not by the level of rates (though historically with IOR fixed at 0% those were the same).

However, in my opinion, the price level is controlled by the level of rates: if the currency’s real yield is higher than the “natural” real yield (risk adjusted), prices will fall. Otherwise prices will rise. It’s that simple, and it doesn’t matter if the base is $1 million or $10 trillion..

“You do whatever it takes to get NGDP expectations up to target, then you supply the amount of base money the public wants to hold at that level of expected NGDP growth.”

Applying my previous two points here, I don’t think there’s a relationship between demand for base and NGDP growth. Tell me what size you want for base and what NGDP level path you want and I’ll achieve them both simultaneously with the right Fedfunds/IOR paths.

I realize that when you fix IOR=0%, thinking in terms of quantity starts to make some sense but once your cost of funds falls down to IOR levels (zero bound), quantity no longer matters.

At this point you usually point out that QE is effective based on observed market moves etc. I think QE has these effects:

(a) Some short term supply/demand in long term interest rate markets. I say short term because eventually long term interest rates will revert to expectations of future short term interest rates, regardless of how many bonds the Fed holds. So really I view this effect as minimal (risk premium related).

(b) A signaling effect: the Fed says “we mean business, we’re not going to raise rateS, and if we do we might have a big loss on our long portfolio and we’ll have to go explain that to congress.” — This effect is real but would trumped by “we hold rates at 0% until NGDP forecast hits target path.” — as in there is NO point in doing both: QE wouldn’t make unemployment drop any faster.

Both effects are due to the purchase of long term interest rate risk. Neither is due to the increase in base and therefore the increased base could be drained out with overnight repo as far as I’m concerned.

Announcing clear interest rate policy fully informs public expectations on future interest rates and therefore fully trumps QE’s only effect at the zero bound: the signaling effect.

17. August 2013 at 20:37

James, I don’t fully understand the bond market’s thought process. I’d guess in a year or two we’ll have a much better understanding as to what is going on right now.

DOB, You said;

“However, in my opinion, the price level is controlled by the level of rates: ”

OK, what path of interest rates would cause the US price level to rise 87 fold over the next 10 years. That’s 8700%.

I don’t think you or anyone else can answer that question. But I can tell you a base increase that would get us in the ball park. That’s where I disagree with this claim of yours:

“Tell me what size you want for base and what NGDP level path you want and I’ll achieve them both simultaneously with the right Fedfunds/IOR paths.”

I simply don’t think interest rates play an important part in the monetary policy transmission mechanism. I think it’s changes in the supply and demand for base money. That’s where we differ.

I see no need to pay IOR. It’s not needed if rates are zero. And if rates are positive then bank deposits at the Fed are so tiny that the welfare cost of no IOR is tiny. The advantage of no IOR is you avoid subsidizing an industry that is already too big. And it makes it easier to understand what’s going on with monetary policy. The HPE is more transparent w/o IOR, and hopefully that leads to better policy over time. With positive rates the base is nearly 100% currency anyway, and there’s no IOR for currency. And if rates are not positive then the Fed’s target is too low.

You said;

“I have issues with the way you think CBs can/should target fx rates (or commodity prices) sustainably without using interest rates, but probably best to not add another layer to the debate.”

Also better not to falsely claim I favor something that if don’t favor. As far as whether they can do so, I think that’s pretty obvious.

As far as “not hitting the path sooner”, I disagree. Suppose your plan takes 3 years. Here’s my plan—peg the price of a 12 month forward NGDP futures contract at the NGDP target. Now the monetary base will automatically go to a point where you hit the target in 12 months, not 3 years.

18. August 2013 at 06:40

“OK, what path of interest rates would cause the US price level to rise 87 fold over the next 10 years. That’s 8700%.”

I didn’t say that there’s a static relationship between interest rates and price increases. Your question is like saying “where would you put your wheel to keep the car on the road?”. Answer is of course: “depends on the road”.

But I’ll humor your question anyway. 87x over 10 year is a rate of continuous inflation of about 45%. Given that the long term natural real rate averages in the ball park of 3%, I’d expect the average rates to be very roughly 48% over that period if the Fed were to target that inflation path. Oh, and I could divide the base by 5 at the same time if you wanted 🙂

“I simply don’t think interest rates play an important part in the monetary policy transmission mechanism. I think it’s changes in the supply and demand for base money. That’s where we differ.”

I agree. I don’t know what the academic split is on that issue. I’m pretty sure Woodford is with me on this one and so are most of the Keynesians. I know Friedman was on your side at least at some point in his career but not sure if he maintained that view until the end. I’d defer to your expertise in economic history.

“The advantage of no IOR is you avoid subsidizing an industry that is already too big.”

That’s precisely one the reasons I want to keep IOR sufficiently away from cost of funds. To keep the base from exploding when rates are low. But there’s also no reason to massively contract it when rates are high. Hence I would keep the spread such that the size of base is roughly constant as a %-age of GDP.

“Here’s my plan””peg the price of a 12 month forward NGDP futures contract at the NGDP target. Now the monetary base will automatically go to a point where you hit the target in 12 months, not 3 years.”

The problem here, in my view, is that the quantity of base does not determine NGDP at the zero bound. You might as well create a futures contract on the incidence of flu in midwestern state for winter 2013/14 and see what level of base would achieve the right number of flu patients..

By the way, if you can go from 3 years to 12 month, why not just use the front month NGDP contract and get it over with in a couple of weeks? Why is 1 year the magic number?

“And if rates are not positive then the Fed’s target is too low.”

Regardless of where you set your target, there will be times when adverse shocks (such as a financial crisis) send the natural real yield below the point where you hit the zero bound. I think negative rates are the best way to handle this and commitment to keep 0% until restored is a distant second best. I think QE is better than nothing but miles and miles below these two.

18. August 2013 at 07:00

By the way, while I think the futures targeting mechanism is not essential, I do think it’s cool. Kind of like the Google car that drive themselves. And it is compatible with interest rate targeting (with rates allowed to go negative):

Fed locks price of first 24 months of NGDP futures contract. Every time Fed buys a contract, they decrease their interest rate for the corresponding date by x bps (where x is a small multiplier). And vice-versa. And of course they regularly publish the current state of the policy rate forward curve so people know where the state machine is at.

By the way, your system would require you to set a multiplier: how much does base increase when Fed buys 1 unit of NGDP risk. I’ve never heard you discuss that.

If you set the multiplier too high, any small player in the market could massively swing monetary policy and that could make it erratic. If you set it too low, all the speculators combined wouldn’t be able to inform Fed policy. So it needs to be set somewhere in between.

18. August 2013 at 10:25

“Imagine that you’re driving along a stretch of highway where the legal speed limit is 55 miles an hour. Unfortunately, however, you’re caught in a traffic jam, making an average of just 15 miles an hour. And the guy next to you says, “I blame those bureaucrats at the highway authority “” if only they would raise the speed limit to 65, we’d be going 10 miles an hour faster.”

Dumb, right? Well, so is the claim that unemployment benefits are causing today’s high unemployment.”

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/10/unemployment-benefits-and-actual-unemployment-an-analogy/

18. August 2013 at 14:23

DOB, You said;

“But I’ll humor your question anyway. 87x over 10 year is a rate of continuous inflation of about 45%. Given that the long term natural real rate averages in the ball park of 3%, I’d expect the average rates to be very roughly 48% over that period if the Fed were to target that inflation path.”

Don’t you think it makes more sense to view 45% nominal rates as an EFFECT of hyperinflation, and 45% annual growth in the base as a CAUSE? I guess if you don’t see it that way I can’t change you mind. But that seems to me to be a more natural way to view the process. If the apply crop is suddenly much bigger, the value of apples falls, and if the supply of base money is much bigger the value of base money falls. We don’t use interest rates to explain the transmission mechanism in the apple market, why use it in the currency market?

You said;

“The problem here, in my view, is that the quantity of base does not determine NGDP at the zero bound. You might as well create a futures contract on the incidence of flu in midwestern state for winter 2013/14 and see what level of base would achieve the right number of flu patients..”

But don’t you see? That’s the beauty of my plan. If it fails you and I get rich by shorting NGDP futures.

Seriously, I don’t ever expect to find a risk free path to riches, and I don’t expect NGDP targeting to fail.

You said;

Regardless of where you set your target, there will be times when adverse shocks (such as a financial crisis) send the natural real yield below the point where you hit the zero bound.”

Absolutely not. If the trend rate of inflation is high then even a huge fall in real rates won’t bring the nominal rate to zero. And by “high” I merely mean at least 4%.

With NGDPLT you could get by with an even lower trend rate of inflation, as Nick Rowe recently showed.

DOB, Your second comment is way off, I’m afraid. I suggest you take a look a my recent Mercatus paper on futures targeting. Elsewhere I’ve have shown how it could work with interest rate targeting, but your set up probably wouldn’t work very well due to the circularity problem. And no, the money multiplier is totally irrelevant in NGDP futures targeting.

dpaff82, Probably dumb right now to see it as the main problem, but the case of Europe shows it can happen in the right circumstances. Recall that the natural rate of unemployment in Europe is around 8%–part of that is labor market intervention.

18. August 2013 at 15:26

Scott,

“Don’t you think it makes more sense to view 45% nominal rates as an EFFECT of hyperinflation, and 45% annual growth in the base as a CAUSE?”

I view it as neither a cause, nor an effect. If you make me Fed dictator tomorrow and ask me to target 45% inflation rate (you would probably not do that but humor me), I would first announce that as being the new target.

If the market questions my credibility/commitment to this target and “fights me”, I would probably have to start by lowering rates. Most likely, the market would eventually cave but overall I would end up with an average rate a bit below 45% + 3%.

If the market got overly scared of “runaway hyperinflation” and thought I would loose control because of conservative scaremongering, I might have to keep short rates above 45% + 3% to keep prices on the path you’ve requested leading to an above expected interest path.

If the market decides to play along, prices will rise along announced target “on their own”, I’ll end up with an interest path very close to 45% + 3%.

Given that it’s impossible to foresee which of these scenarios would play out, I picked the middle path to humor your question, but I do not imply any certainty or causation there. And by the way tripling the base did not triple the price level over the past 5 years…

“We don’t use interest rates to explain the transmission mechanism in the apple market, why use it in the currency market?”

If I opened an institution that printed “apple certificates of deposits” (ignoring perishability for a minute) so you didn’t have to carry your apples around, it is fairly clear that if people brought 10x as many apples for me to store and therefore I issued 10x as many certificates, the price of apple would not be affected. We’d have to look at interest rates then, or the (relative) cost of carry of certificates vs apple.

OMO do not create wealth like Apple trees do. OMO substitute one nominal asset for another (like my Apple certificates) and therefore do not affect the price level unless they change the yield of nominal asset (nominal rates). That’s why looking at interest rates makes sense. Money is not like Apple. Money is like Apple certificate of deposits.

“If the trend rate of inflation is high then even a huge fall in real rates won’t bring the nominal rate to zero. And by “high” I merely mean at least 4%.”

How did you go from high to huge? Are you implying that by raising inflation path by 1%, we could withstand falls in real rates by MORE THAN 1% worse than if we didn’t? (I could probably be convinced of that, actually. Just want to make sure that’s what you’re saying)

“With NGDPLT you could get by with an even lower trend rate of inflation, as Nick Rowe recently showed”

Agreed.

“I suggest you take a look a my recent Mercatus paper on futures targeting. [..] And no, the money multiplier is totally irrelevant in NGDP futures targeting.”

I wasn’t talking about the money multiplier when I said multiplier, just that there’s a scale factor to be set somewhere. I skimmed your paper and you wrote:

“For instance, each $1 purchase of a long position in an NGDP futures contract might trigger a $1,000 open-market sale by the Fed.”

Looks like you’re going for a scale factor of 1:1000. So it sounds that you’ve mentioned that scale factor and therefore I take back my statement. Let’s cut that thread of conversation since we’re not in disagreement.

18. August 2013 at 15:30

Scott,

Just to clarify, when I wrote “Let’s cut that thread of conversation since we’re not in disagreement.”, I meant on the particular subthread of money multiplier.

I very much welcome your response on the other points and am grateful that you’ve been responding to my comments so far, especially given the volume of comments you’re getting.

18. August 2013 at 18:07

If we allow the central bank to bankrupt itself (and the government too), then pegging a GDP future will definitely “work” at the zero bound – that is, you will hit the target. But what comes next? Overshoot.

So what’s the point? You can hit the target simply by raising future GDP targets. This makes the tradeoff clear: you can hit the target only by overshooting future targets. No free lunch.

Alternatively, you could theorize that central bank purchases (regardless of whether they expand the base) can work by some non-monetary mechanism, some financial friction. But Scott never talks about that.

18. August 2013 at 18:40

The most powerful tool a central bank has is setting the redemption value of money. This doesn’t necessarily have to be in terms of something that is deliverable – it could be a price index, for example. (In the event that redemption was actually required, it would have to be something deliverable).

Once a redemption value is chosen, the quantity of (fixed 0%) money isn’t really discretionary. So you can work backwards and deduce the redemption value from the quantity, as monetarists like to do. If the quantity changed by 87x, then we can deduce that the central bank changed the redemption value by 87x.

18. August 2013 at 23:43

DOB, I’m afraid I don’t follow your apple example at all. I’m not sure what apple CDs are, or why the value of apples would not fall if the harvest was ten times as large as usual. If the value of apples falls, then the value of a claim to an apple falls.

You said;

“OMO substitute one nominal asset for another (like my Apple certificates) and therefore do not affect the price level unless they change the yield of nominal asset (nominal rates).”

This is clearly false. Think of a doubling of the money supply in an economy with perfectly flexible wages and prices. In that case the price level immediately doubles, and no real variables are affected. Nominal interest rates are unchanged. I’ve just described the long run equilibrium, and even Keynesian economists agree that money doesn’t affect interest rates in the long run. So obviously interest rates cannot possibly be a necessary condition for the transmission mechanism, otherwise monetary policy would not be neutral in a world of perfect wage and price flexibility.

BTW, when Exxon doubles the number of shares of Exxon stock outstanding, they simply sway one nominal asset for another, and yet the price of that asset (Exxon stock) falls in half.

My point about the zero bound was simple. This recession saw the first zero bound in more than 50 years, and did so with an inflation target of 2%. At a 3% inflation target zero bounds would occur much less often (assuming real interest rate fluctuations are normally distributed), and at 4% they would be far rarer than at 3%. Obviously anything is possible in theory, so I can’t completely rule out a zero bound, even at 4% trend inflation.

I’ll be traveling so replies may be few and far between.

Max, I’m not sure I follow all that. Central bank default is the least of our worries in America. The Fed is earning the largest profits ever earned by any entity in all of human history.

19. August 2013 at 02:15

Scott,

Wow. I think we’ve finally zoomed in on the main disagreement. Great 🙂

Let me first clarify my Apple CDs example:

I’m running an “Apple bank” where people (mostly Apple farmers) come by to drop off their Apples and I issue them a certificate of deposit for each Apple (assume Apples are fungible and not perishable). They can then use these CDs to trade in the market place. If they exchange an Apple CD in exchange for a sheet from a sheep farmer, the sheep farmer can come to the Apple bank and redeem his Apple CD for the physical Apple, or he can trade it for yet something else.

Apple trees in that world produce a very stable and predictable supply of 10,000 Apples per year and demand is also very stable so that the real price of Apples is quite stable.

Last year, my Apple bank didn’t exist so there were 0 Apple CDs outstanding. This year, I’m just getting started and issued 10 Apple CDs. Next year, my business will really take off and have a cumulative 100 Apple CDs outstanding.

Does that mean that the price of Apples (or Apple CDs) is going to go down 10-fold from this year to next year?

Of course not, the price of Apple CDs will track the price of Apple and the price of Apples will continue to be what it’s always been.

The net supply of Apples is unaffected by Apple CDs: Apple CDs are zero sum–the Apple bank liabilities are someone else’s asset.

“This is clearly false. Think of a doubling of the money supply in an economy with perfectly flexible wages and prices. In that case the price level immediately doubles, and no real variables are affected.”

I’m in strong disagreement with this. Are you saying that if it wasn’t for rigid prices, the price level should have trippled in the US over the past 5 year??

You mention “long term”. So if we switch to Japan instead, is 20 years long term enough? I don’t have data on the Japanese base but I assume it went up quite a bit over the past 20 years. What about their price index?

Doubling the money supply (via OMO as opposed to a stock-like split) doesn’t mean halving its value even with perfectly flexible prices.

“BTW, when Exxon doubles the number of shares of Exxon stock outstanding, they simply sway one nominal asset for another, and yet the price of that asset (Exxon stock) falls in half.”

Stock splits aren’t comparable to OMOs. If the CB said: “everyone who’s got $1 now has $2”, of course the price level would double instantly (and I think all nominal assets and labor contracts would get redenominated also).

OMOs are more like Exxon issuing more stock. If it did so in an amount equal to the existing market cap, the supply of Exxon stock would double. Yet, if the market believed Exxon could generate the same RoE on the freshly sourced capital than on the old one, the price of the Exxon stock wouldn’t budge! (at least up to first order effects)

“At a 3% inflation target zero bounds would occur much less often (assuming real interest rate fluctuations are normally distributed)”

Fully agreed. And I was also assuming some kind of normal distribution (probably with fatter tails) so that there’s always a chance of hitting the tail event no matter how high you set the bound. The social costs of hitting the low probability event are enormous though.

Chiming in on your convo with Max:

“Central bank default is the least of our worries in America. The Fed is earning the largest profits ever earned by any entity in all of human history.”

That’s because it’s got lots of risk and it could easily be making the largest losses any entity has ever made at some point in the future. (Though granted that mostly means NGDP went up)

19. August 2013 at 09:04

I was sloppily thinking, “if speculators manage to bankrupt the Fed, then it will hit the GDP target against its will” – but if it hits the target, then it won’t have to pay out anything. So what I wrote doesn’t make any sense.

However, the Fed would have an incentive to hit the target in order to avoid losses.

The question is, how does it hit the target when constrained by the zero bound? And the answer is, by raising future targets. In monetarist lingo, if it “permanently” increases the base to hit the target, it will necessarily overshoot future targets. If it only “temporarily” increases the base, it will miss the current target. The original target path is not feasible (in the absence of successful non-monetary interventions, like credit easing or something).

19. August 2013 at 09:34

DOB, Now I see your mistake. Cash is not like apple CDs, it’s like apples! So a doubling of the supply of cash is like a doubling of the supply of apples. And even you agree that more apples will reduce the value of apples.

Cash can no longer be redeemed into gold. If it could, that would make your CD analogy apt. But in that case gold would be the MOA and we’d model the gold market to determine NGDP. Indeed I once did so and have a book coming out next year on this very topic.

Monetary injections are only inflationary if they are permanent. And for all intents and purposes “permanent” means “until nominal rates rise above zero.” (Not exactly, but close enough for our purposes.) That’s why the QE in the US and Japan have not raised prices. Your 20 year remark (actually 15) is misleading, as Japan’s been at the zero bound that entire time. If we ever reached a point where the zero bound was permanent then cash and bonds would be perfect substitutes and OMOs would do nothing. In that case you redefine the base as all zero interest Treasury liabilities, and monetary policy consists of trading those for other assets. Indeed the national debt would effectively be 100% currency.

How do we know the Japanese QE is temporary? Because they reduced the monetary base by 20% in order to prevent inflation from rising above zero. And they succeeded! So whenever people talk about Japan they should recall that it’s a shining example of successful QE. The BOJ got exactly the outcome they wanted–flat CPI for 20 years. The problem is that the BOJ’s target was too low, not that QE doesn’t allow them to hit their target at zero rates.

Max, I contemplate the Fed buying up all of planet Earth if necessary. It will hit the target at the zero bound, that’s not the issue. The issue is how much risk to you want to expose the Fed to? As a practical matter they would never have to go beyond buying T-debt to hit a 5% NGDPLT. But if needed they should buy foreign government bonds as well.

19. August 2013 at 10:05

Scott, “I contemplate the Fed buying up all of planet Earth if necessary. It will hit the target at the zero bound, that’s not the issue.”

How does it avoid overshooting future targets? If you answer, “by selling the assets it bought to hit the last target”, then you are talking about a temporary increase in the base, which you just said was not inflationary.

Or else you believe that temporary increases in the base are inflationary, if you do enough of it. (This is a perfectly respectable position to take, but I would argue that it’s not monetary policy, narrowly defined).

19. August 2013 at 10:17

Scott, “Cash can no longer be redeemed into gold. If it could, that would make your CD analogy apt. But in that case gold would be the MOA and we’d model the gold market to determine NGDP. Indeed I once did so and have a book coming out next year on this very topic.”

The MOA is CPI (or whatever index the Fed likes). Money is still redeemable, it’s just not pegged to anything at the moment.

20. August 2013 at 15:20

Scott,

“Now I see your mistake.”

Well, mine and Woodford’s and a whole bunch and other guys’, right? 🙂

“Cash is not like apple CDs, it’s like apples!”

Why is it like Apples? The central bank creates cash by exchanging it either against a repo or a short-term Treasury bond (in normal times). Both of these are “safe” assets who’s price is pretty 1:1 in terms of cash at all times (like Apples vs. Apple CDs).

Cash is effectively a “certificate of deposit of safe nominal assets” much like the Apple CD is a “certificate of deposit of Apples”.

Bonds and Apples don’t flow through payment systems easily. Cash and Apple CDs do.

Cash can be redeemed into said nominal assets at any time. Generally that’s done in the market though functionally, it’s as if it was done at the Fed since the Fed is there in the market making sure those transactions happen at the interest rate that it has set.

“And even you agree that more apples will reduce the value of apples.”

Of course.

“Cash can no longer be redeemed into gold.”

Correct, cash can be redeemed into interest bearing nominal assets. When the Fed redeems cash, it doesn’t subtract from the net supply of nominal assets, it just swaps one for another. That’s why the price level is unaffected unless the expected real return of nominal assets is moved in the process (nominal rates minus expected inflation)

“Your 20 year remark (actually 15) is misleading, as Japan’s been at the zero bound that entire time.”

The price of Apple drops when the supply of Apple increases (ceteris paribus), even at the zero bound.. The fact that you have to qualify your quantity argument based on where nominal interest rates are is, I think, a hint that interest rates aren’t as irrelevant as the price of zinc (to use an example you had given me before).

“Monetary injections are only inflationary if they are permanent. And for all intents and purposes “permanent” means “until nominal rates rise above zero.””

I agree with that but I think it’s a convoluted way of looking at this. And I think it is strictly better for the Fed to say it will inject excess reserves when inflation picks up (or in their language, keep interest rates at 0%) than to inject reserves today which could be drained away instantly (like the punch bowl when the party gets started).

Do you not expect them to drain reserves once inflation picks up? That would mean they would let the price level triple relatively rapidly if I understand your quantity-based model correctly?

26. September 2013 at 06:04

[…] Six weeks ago I did a post on the puzzling fall in unemployment claims: […]