The myth of the pro-German ECB

The ECB likes low inflation. So does Germany. That has led many people to wrongly assume that ECB policy is somehow pro-German.

In the long run the trend rate of inflation makes no difference; money is super-neutral. Greece and Italy are no better or worse off with a 2% trend rate of inflation, or an 8% trend rate (except for second order effects such as the distortions produced by the taxation of nominal income from capital.)

I recall attending a European economics conference about 6 or 7 years ago, and hearing German academics complain that ECB policy was appropriate for high-flyers like Spain and Ireland, but too tight for Germany. At that time Spain and Ireland had relatively high inflation (Balassa-Samuelson effect), and since the ECB was targeting average inflation, this meant slow-growers like Germany suffered from an excessively tight policy.

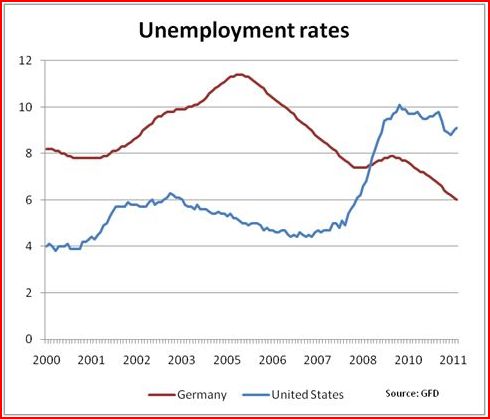

People forget that as recently as 2005 (when the world economy was doing well) Germany was viewed as the sick man of Europe. Unemployment had risen steadily to nearly 12%. It was viewed as a failed economic model. Too rigid, unable to adopt to the post-industrial 21st century. No one was talking about ECB policy favoring Germany, just the opposite.

How quickly things change, and how soon we forget. Germany is not doing better because it’s favored by the ECB; they were too tight for everyone in 2009. Rather it’s because labor market reforms put their wage costs in line with the ECBs tight money policy after 2005. It was a successful “internal devaluation.”

Here is graph showing the unemployment rate in Germany:

It may have been inevitable that the euro would crash and burn, but it might just as well been in 2005 when Germany was weak and Spain was strong. The problem is one-size-fits-all, not a pro-German slant.

This WSJ article discusses how Sarkozy is trying to emulate German labor market reforms:

The government’s employment proposal is designed to stop the job hemorrhage by providing companies with a buffer to keep their staff while still cutting payroll when business shrinks. During the 2009 recession, Germany limited job losses in part because of a popular subsidy program for short-hours work, known as Kurzarbeit. At the peak, in May 2009, as many as 1.5 million workers were in the program. German unions also have made wage concessions to preserve jobs.

. . .

The French government’s idea to increase work-time and pay flexibility is likely to meet much more resistance.

“All labor unions will say ‘No,’ because that would amount to making workers pay for the economic downturn,” said Mourad Rabhi, a leader at CGT, France’s second-largest union. “And in France there isn’t the same climate of mutual confidence between workers and companies, as in Germany.”

BTW, I agree with Tyler Cowen that Germany is well placed to do well in the future. Tyler mentions good governance, which in my view is partly related to cultural factors like civic virtue. But the relative performance of Spain and Germany around 2005 shows that these factors aren’t very useful for short term predictions. So don’t assume the current perception that Germany is the “strong man of Europe” will hold forever. History teaches us to expect the unexpected.

PS. Tyler Cowen is pretty cagey. He didn’t actually say he agreed with the quotation he provided; rather he said he hasn’t made up his mind. But the quotation he provided was his own words. I need to remember to do predictions that way in the future. 🙂

PPS. The always interesting Ambrose Evans-Pritchard has some cheerful predictions for 2012.

Tags: Germany

3. January 2012 at 06:48

Scott If you look at it from an NGDP prism, you´ll observe that ECB rate action since 2005 has been consistent with the behavior of German NGDP, totally ignoring NGDP of the rest.

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2011/09/21/%E2%80%9Crevenge%E2%80%9D/

3. January 2012 at 07:20

Inflation encourages spending over saving, which increases the power of gvt. over its people. Meanwhile, high savings increases the power of private people over gvt.

Therefore, in the long run, low inflation is always preferable.

3. January 2012 at 07:50

You could add yourself to the mix too Scott. Germany likes low wages, the ECB likes low wages, and you like low wages. Of course if tomorrow Geramny stopped liking low wages you and the ECB would feel less good about Germany

3. January 2012 at 08:16

An interesting perspective. I have always assumed the ECB has not acted “pro-German” but rather “pro-a powerful, strong economy” which currently happens to be Germany. If Italy and Greece were currently the well-off economies, and Germany was the struggling economy on the verge of crisis (some would say already in crisis) how would ECB policy be different (if different at all)? That is, would that first sentence of this post read differently if since 2007 or so, Germany was struggling, while Italy and Greece were the “strong men of Europe.” My guess is that since a perfect “one-size-fits-all policy” is impossible (as each country prefers a slightly different policy), the realistic “one-size-fits-all policy” would tends to slightly favor the stronger, more powerful economies (currently happening to be Germany).

3. January 2012 at 08:23

Marcus, Yes, but prior to 2005 the ECB was favoring the PIGS, and was way too tight for Germany.

Morgan, I agree, but only because our tax system isn’t indexed. Or because we tax saving. Make either change and then inflation is no longer anti-saving.

Mike Sax, You have a habit of misrepresenting my views; I don’t “like” low wages. And Germany certainly doesn’t have low wage—they have some of the highest wages in the world.

If you plan on continuing to misrepresent my views, you might provide some quotations.

3. January 2012 at 08:24

Morgan, That might be right. Or it could simply be that they target inflation.

3. January 2012 at 09:21

Scott, I’m glad you agree that until we tax spending, we should prefer low inflation.

—

Now let me push you more.

Think of a saved dollar a unit of power to be used against the govt. for the benefit of private interests.

Basically see money as exactly the opposite of how MMT views it…

Money is an necessary creation meant to clearly admit who the most valuable players in society are. The money that they have and have amassed comes from skills and talents that others don’t have.

Gvt. ONLY legitimately handles the monetary policy because it reflects the wills of these select people.

If the govt. tries to use monetary policy to the detriment of the people who are valuable, the gvt. will fall.

And, these people DECIDE is the policy is in their interests… so none of your inflation is good for savers junk (one of your weakest arguments).

Money is not a social tool. It is not a social good. Money is not a tool for Democracy. Money much like math, has no say over who is good at it, who gets it, or who does the most with it.

And in this light, even considering indexing or taxing consumption, inflation is always pro-gvt.

3. January 2012 at 09:27

Obviously when I say you like low wages I am paraphrasing. You never literally said such a thing but that’s what your policy prescription on things like the minimum wage amounts to.

I have not tried to misrepresent your views, you may not like my interpretation here but it’s not a misrepresentation. Indeed everyone uses the paraphrase, to require me to locate the exact chapter and verse of anything I say regarding your position puts an unfair demand on me not required of others here or of anyone in normal discussion.

My previous missive about you saying that had Strong not died there would be no Depression was not a misrepresenation either by the way.

You said that in respone to me in the comments section in a previous post. I’d have to look through the archives to find it. It’s possible you meant it tongue in cheek.

I don’t operate in bad faith though it is true sometimes I paraphrase-as is perfectly normal.

Overall my impression that it is your view as it is the view of many I would call Right of Center economists that we could see a sizable level of employment if we lowered the minimum wage, weakened collective bargaining rights, and cut unemployment benefits.

You “like” low wages or at least think that they would be helpful for business right now and could jump start the economy. This is not a misrepresenation on my part but my impression of your view.

In addition, regarding the current discussion of this post, I think that you see the German experience since 2005:

“Germany is not doing better because it’s favored by the ECB; they were too tight for everyone in 2009. Rather it’s because labor market reforms put their wage costs in line with the ECBs tight money policy after 2005. It was a successful “internal devaluation.”

My gloss on this is that you favor these “labor reforms” and would like to see something on its order done in Greece, Spain, Italy, and indeed the U.S.

In a way your pushing an open door here as the U.S. has seen stagnant wage growth during this recovery which was previously unheard of-a recovery with totally flatlining wages.

3. January 2012 at 09:35

OT, sorry, but Svensson is superb in the Riksbank minutes again, with a great discussion of “uncertainty” and monetary policy on p31.

http://www.riksbank.com/upload/Dokument_riksbank/Kat_publicerat/PPP/2011/pro_penningpol_111219_eng.pdf

Nyberg’s comments on Europe are good too.

3. January 2012 at 09:35

Scott: “prior to 2005 the ECB was favoring the PIGS, and was way too tight for Germany.”

Is a market monetarist allowed to say that policy is tight when NGDP is growing at a steady rate? Take a look at the rising dark line on the chart by Kantoos:

http://kantooseconomics.com/2011/01/27/what-about-real-gdp-in-germany/

3. January 2012 at 10:11

Mike Sax,

“I have not tried to misrepresent your views, you may not like my interpretation here but it’s not a misrepresentation”

You’re an authority on the first clause, but surely not the second! We don’t get to decide whether or not we’re misrepresenting people.

I think that “liking” is a weird way to put such a position. It’s like saying that doctors “like” giving chemotherapy.

“Overall my impression that it is your view as it is the view of many I would call Right of Center economists that we could see a sizable level of employment if we lowered the minimum wage, weakened collective bargaining rights, and cut unemployment benefits.”

“Low wages” is a lousy way to put it, since surely the idea is not to lower wages in the aggregate in any sense but rather to prevent the redistribution of wages away from high PARTICULAR wage + lower employment levels to lower PARTICULAR wage + higher employment levels. As I understand it, the goal isn’t to change average wages across the workforce but to “price in” people who would otherwise be unemployed via changing the wage structure.

3. January 2012 at 10:18

Scott, you preach that good MP is to follow GDP tendency.

If that is right your post is false.

If the post is right, your theory is false.

The ECB has been quite faithful to German NGDP.

3. January 2012 at 10:22

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2011/09/is-it-time-for-eurozone-to-get-rid-of.html

the two graph of Beckworth are very very clear

3. January 2012 at 10:57

Scott

I agree with Kevin and Luis on this one. As the link I put up show, before 2005 both Germany AND the rest were evolving close to trend. After 2005, the story is very different. Even Trichet acknowledged that the “ECB did even better than the Bundesbank in its heyday”!

3. January 2012 at 11:01

There is a dramatically different interpretation of the evidence you present that is equally consistent with Germany’s renewed growth…

Some additional facts:

– Euro exchange rate peaked in 2008, after a decade long climb

– Euro exchange rate is without question being dragged down by risk created by peripheral countries; in essence, the Greek crisis has dramatically benefited German exports

– German export surpluses are driven by industries that, as a group, have seen relative strength vs. other industries (notably manufacturing equipment, such as seen a high demand from China and developing countries)

– German funding costs are exceptionally low even as neighboring country costs ave diverged upwards

In essence, the ECB’s policy is forcing divergence between funding costs in the core/periphery (with italy now periphery). This enhanced risk to the ECB’s balance sheet is forcing down the Euro vs. the dollar, and strengthening exports further – Germany has a large export surplus. In other words, Germany is benefiting substantially from the weakness of its neighbors.

ECB policy is currently not only benefiting Germany, but it is DIRECTLY benefiting Germany AT THE EXPENSE of other countries.

Luis Arroyo notes Beckworth’s arguments that the ECB policy is appropriate for Germany. You argue that ECB policy in the 2004ish period was appropriate for the periphery. The data is in the middle – German real gdp growth was 1-1.5% in 2004 to 2005, and close to 3% in 2006/2007. Prior to that, German growth was horrid, true.

Your best argument is that German decrease in unemployment preceded the decline in the Euro (the euro kept rising through 2007, but German unemployment improved starting in 2005/2006). The partial counter to this is that much of German exports were specifically to peripheral countries (also Euro funded) which paid for these imports using German-provided credit, and the 2000s saw a structural shift that favored German companies.

A now-forming view among many observers is that the ECB and Euro technocracy is actively engaged in fiscal management of the European states – they’ve essentially said that. They are actively rolling back transfer payments. [insert Morgan’s plug for Mundell here] Your argument above is consistent with that.

I agree with Cowen – as I’m sure you could have guessed – that German good governance is key to their success. Their weakness is their aging population. Having said that, I strongly suspect there is a correlation between strong controls on immigration/citizenship and good governance. If only because good governance is akin to a public good, and uncontrolled access tends to destroy it. Historically, in the US, cities with the highest level of uncontrolled immigration also had the worst machine politics and nepotism… I say uncontrolled immigration because selecting immigrants for specific skills/wealth/health/youth is a sign of good governance – just go ahead and try to immigrate to New Zealand.

Anway, really really nice post. Challenges conventional wisdom.

3. January 2012 at 11:12

W. Peden if I understand your position it is that the choice is between a higher particular wage and lower employment or a lower particular wage and higher employment and that you and presumably Scott prefer the latter?

I’m not willing to agree that this is the choice. If it were I doublt either will bode well for the “aggregate” economy.

I’m somthing of a skeptic about certain uses of aggregate. Like you seem to be talking here of “aggregate income.” I just think aggreages sometimes obscure a clear picture of things.

For example when it is pointed out that median wages have staganated since the late 70s, Right of Center economists try to divert things by pointing to per capita income.

But the use of such aggreages can be misleading. Right now if I was a Right of Center economist how would I answer this point about median income stagnation?

I’d change the subject. Actually first of all I’d call the Wall Street Journal and see if they’d let me write and editorial.

In writing the piece I’d point out that this talk of median incomes stagnating is small beer, what counts is that average income is way up. In this way conservative economic policies have worked.

But the statistical average of American income is acstually higly misleading. It sounds good-over $200,000 per year-but the small outlying top obscures things.

In reality the median American income is currently still under %50,000. In the case of income, the statistical average is misldeading as the small top levle of income earners distorts the picture.

Most Americans don’t make a fourth of $200,000 a year so median gives the more accurate picture. In statistics, “average” may not be at all average.

3. January 2012 at 11:14

Scott,

In addition to the nominal GDP graphs mentioned above, there are several studies that reach similar conclusions using Taylor Rules. I posted one here: http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2011/06/ecb-monetary-policy-mess-in-one-picture.html

Another point is that ECB was shaped after and inherited the culture of the German Bundesbank. There is no way the Germans would have joined the currency union had they expected the ECB to be run any differently than how they ran their German central bank.

3. January 2012 at 11:40

David Beckworth,

I remembered that post of yours but I didn’t recall that you wrote it. I’ve searched for it whenever I see somebody claiming, as Scott does, that the ECB is even-handed.

3. January 2012 at 11:44

Morgan, No, I don’t agree.

Mike Sax, It’s true that some right of center economists favor wage cuts, but I favor stimulus.

To suggest that opposition to minimum wage laws means you like low wages is ludicrous.

I think you made up the quote about Strong and the Depression; I doubt I ever said that.

Thanks Britmouse, I wish he was on the Fed.

Kevin, Good point. My hunch is that the unemployment was partly slow NGDP growth (especially during 2001-05, when it clearly slowed a bit from the 1990s pace) and partly structural factors. I didn’t mean to imply that ECB policy was the sole cause of high unemployment in 2005–that’s clearly wrong.

Luis, I don’t follow your comment. I’m not claiming that ECB policy was good, I’m claiming they aren’t pro-German. Sometimes their policy happens to favor Germany, and sometimes it doesn’t.

Marcus, I don’t agree with where you drew the trend line. NGDP growth in Germany during 2000-05 was below 2%, that’s clearly below trend, and below the growth rate of the 1990s. That’s one reason why unemployment rose so much (but not the only reason.

I’m not saying that 5% is trend in Germany, but it’s surely more than 2%.

Statsguy, A few comments:

1. I agree that the post-2008 period has helped Germany, for the reasons you cite.

2. But German unemployment fell during 2005-08, despite a strengthening euro.

3. RGDP is misleading, both NGDP and unemployment data suggest policy was too tight for Germany during 2000-05.

4. I agree about good governance, but recall that their economy was doing poorly in 2000-05, despite good governance. Contrary to what many assume, German per capita GDP (PPP) is pretty typical for Northern Europe (the Nordics plus Britain, France, Belgium, Switzerland, Austria)– below some countries and above others.

Germany’s done better than Britain and France in recent years, but 8 years ago it was doing more poorly–these things are cyclical.

I agree that we do better with controlled immigration, but arguably the world does better if we have uncontrolled immigration.

3. January 2012 at 11:57

David, See my response to Marcus, I think the NGDP data supports my point. German NGDP growth was well below the EU average during those years, and below its own previous growth.

You said;

“There is no way the Germans would have joined the currency union had they expected the ECB to be run any differently than how they ran their German central bank.”

I certainly agree with this, but that doesn’t mean it favors Germany. These things are cyclical. On average monetary policy will be just right for both Germany and Spain, but at times it will be too expansionary, and at times too contractionary, for each country. It should balance out in the long run. Right now it tends to favor Germany, but a few years back it favored the PIGS.

I’m not a fan of the Taylor Rule, the Fed also deviated during this period.

I see the basic problem as “one-size-fits-all”, not that it favors any one country.

3. January 2012 at 11:59

I should add that one-size-fits-all wasn’t the problem in 2009–it was too tight for everyone.

3. January 2012 at 12:18

“But German unemployment fell during 2005-08, despite a strengthening euro.”

Yep, I noted that – my gut reaction was skepticism until I looked at the data. That’s why I thought the post was so great!

“I agree that we do better with controlled immigration, but arguably the world does better if we have uncontrolled immigration.”

Not necessarily – the arguments for controlled immigration are _almost exactly_ the same arguments as for private property ownership. aka, it’s the tragedy of the commons. I frequently wonder why libertarians don’t see the connection? I tend to think it’s because they are suspicious of all public goods and they view free migration as a way to destroy/minimize public goods, but the ONE public good that libertarians should NEVER be suspicious of is good/uncorrupt governance, and there is a strong argument this requires secure borders.

All of that is notoriously counter-productive. Libertarians should be all for freedom of EXIT, but very much in favor of restricted entry to maximize incentives for countries to invest in good governance. My suspicion is that the real reason libertarians so often favor unrestricted entry is that this offers a way to reduce the bargaining power of labor in developed countries… But if the single most important long run determinant of growth is good governance (which Tyler Cowen may also agree with), then this should dominate the short-run advantages of labor equalization EVEN FOR CITIZENS IN UNDEVELOPED COUNTRIES.

3. January 2012 at 13:04

“I think you made up the quote about Strong and the Depression; I doubt I ever said that.”

Scott, what can I tell you? Certainly we can disagree and not be bad people. But to claim that I engaged in willful misrepresentation is another thing. You yourself doubt you ever said it which leaves room for doubt on your part too.

To while not being sure yourself, question my good faith I think is a little over the top. As you have questioned it I guess I will see if I can find it. I did admit that you may have said it tongue in cheek but I do remember you saying it.

3. January 2012 at 13:15

StatsGuy,

As a libertarian who was very vocal in 2006-2008 when illegal immigration was a prominent national issue, let me throw a wet towel on your idea there. Most libertarians come to their policy positions from basic principles, e.g. freedom of movement. I’ve always been in favor of an immigration overhaul, which would make legal immigration much more efficient and attractive, and strict penalties for illegal immigration (with leniency in the interim). This was not a popular position among beltway libertarians at the time, who generally loathe anything that smells of “racism,” and they strongly opposed the movement on the populist right for “secure borders.” Since then the mainstream among libertarians has become more like my position: easier legal immigration, some level of enforcement or at least anti-fraud, and ending drug prohibition (taking the profit out of illegal border crossings). They still are not in favor of “building a fence”, but that really is a simplistic idea anyway. Like so many things discussed on this blog, it’s a demand issue; fix the demand problem and the rest will sort itself out.

3. January 2012 at 13:37

Money is not superneutral (except at high inflation rates) if wages are downward sticky (and indeed money is not superneutral at high inflation rates, because they result in inefficiently low cash holdings and costly price adjustment, so unless wages are flexible downward, money is not superneutral at all). This is true even in economies like the US which are reasonably homogeneous and have high internal labor mobility. It’s much more true in economies like the Eurozone, which are more segmented and have relatively low labor mobility.

Now it’s true that the problems can go (and have gone) either way, hurting Germany at one time and helping it at another. But this is just an example of the non-superneutrality of money. If Europe’s inflation rate had been higher all along, Germany would have been in better shape in 2005, but the rest of the Eurozone wouldn’t have been that much worse off; and the rest of the Eurozone would be in better shape today, while Germany wouldn’t be that much worse off; collectively, unemployment would be lower in the Eurozone, both in 2005 and today.

3. January 2012 at 13:39

Mike Sax,

I’m not staking out a position either way at this point; just trying to clarify matters.

There’s the split of wages across the workforce. In the former case, when people talk about “curing structural issues” and so on, they don’t mean reducing wages in aggregate, but permitting a better split across the workforce i.e. between the employed and otherwise unemployed. One can disagree with that position for various reasons, but it’s not about reducing AGGREGATE wages i.e. the amount of profits spent on wages and instead about distributing them in such a way as to minimise unemployment.

You can compare this with plans to allocate more profits to wages rather than dividends: the aim is not to reduce profits, but to have them distributed in such a way as to maximise wages.

PS. I recommend looking at compensation rather than incomes, as a general rule. There are a lot of ways to take compensation off the tax form and they’re attractive if there are rewards for doing so e.g. tax incentives for employer-provided health insurance.

3. January 2012 at 13:41

I would say that, on average, the ECB is pro-German simply because Germany is larger than the other members of the Eurozone. If you target the average, (assuming you set a reasonable target) you’re setting a target that’s necessarily reasonably close to being appropriate for Germany but may not be at all appropriate for much of the rest of the Eurozone. Thus we see the PIIGS in much worse shape today than Germany was in 2005 (even relative to the condition of the overall world economy).

3. January 2012 at 13:43

Cthorm,

I think that the ideal libertarian position should be more or less total freedom of movement. That’s what Friedman et al believed in. However, such a situation is only possible if people can’t migrate for welfare. It’s perhaps the single most overlooked way in which the welfare state restricts liberty: it’s hopefully obvious that people in the Third World should be able to easily get jobs in the First World rather than starve to death, but no country is going to allow that if the said Third World people can simply milk the welfare state.

Let’s not overlook Obama’s successful solution to the US’s immigration problem: let things get so lousy that no-one wants to risk their lives to get in. (With thanks to South Park.)

3. January 2012 at 14:02

Is there any actual evidence that Germany’s relative success is the result of its labor policy reforms? I’ve seen that asserted elsewhere as well, but I’ve not seen anything that actually backs that up. Intuitively, it seems like there would be a mismatch of magnitudes to me (i.e., the reforms seem unlikely to have that large of an impact).

3. January 2012 at 14:10

W. Peden, in this case this can’t be sold as helping businesses with tight profit margins, etc as the disitribution is changing rather than the aggregate amount.

Actually one way that tends to be more on the Left than Right of redstibuting wages to increase employment is a proposal that we should shorten the work week.

Not necessarily advocating this at this point but this would seem to be an idea that does what you are talking about but in this case most Right of Center economists don’t like the idea.

3. January 2012 at 14:12

Scott it’s hard to find in your archives as you have quite a few posts-which is a good thing.

I will look around for it. I do think accusing me of deliberately making it up is a little gratiutious on your part.

3. January 2012 at 15:46

you

“Morgan, I agree, but only because our tax system isn’t indexed. Or because we tax saving. Make either change and then inflation is no longer anti-saving.”

me

“Scott, I’m glad you agree that until we tax spending, we should prefer low inflation.”

You

“i don’t agree”

Me

ROFL.

Your bugaboo is a nice little thing Scott, but mine – keeping gvt. at bay trumps yours.

Ask Uncle Milton.

3. January 2012 at 15:49

Statsguy, I’m all for good governance, but I don’t see how moving people around makes governance worse on average.

Mike, OK, I’ll just assume you made a mistake. I probably said something like “if the monetary policy of the 1920s had been continued (stable NGDP growth) there would have been no Great Depression.”

Cthorm, In my view the problem of illegal immigration would mostly vanish if we allowed more legal immigration (say 3 or 4 million per year, which would still leave population growth below 2%.) Indeed illegal immigration has fallen sharply in recent years. I agree that unlimited immigration is politically unrealistic right now, regardless of its merits in utilitarian terms.

Andy, I agree that money is not precisely super-neutral, although it’s approximately so in the 2% to 8% inflation range. But I slightly disagree with this:

“Now it’s true that the problems can go (and have gone) either way, hurting Germany at one time and helping it at another. But this is just an example of the non-superneutrality of money.”

This problem is not necessarily related to non-superneutrality, and indeed would occur at a trend inflation rate of 10% or 15%, a range over which everyone agrees money is roughly superneutral.

The one size fits all problem occurs because even with a 2% overall inflation target, NGDP growth will vary greatly over time in each country. The same problem occurs with 8% trend inflation. I agree with the rest of your post, so maybe previous comment is an unimportant quibble on my part.

Regarding your second comment, imagine the eurozone divided up into regions with 5 million people. I.e regions like Denmark, or half of Belgium, or 1/16th of Germany. forget about national boundaries. Does the ECB favor one of those 5 million people regions over another?

Adam, I’m no expert there, I relied on what others have said. I don’t have a strong opinion on the issue.

3. January 2012 at 16:02

[…] The myth of the pro-German ECB. […]

3. January 2012 at 16:11

Scott,

I haven’t forgotten how they spoke of Germany in 2005. You can look up an old Tom Friedman NYTimes article where he calls Germany a dinosaur and Ireland the future and says that German policy needs to emulate Ireland to succeed.

Context is everything. One of the reasons I like your perspective.

3. January 2012 at 16:40

Mike Sax,

You may be remembering what I said about Strong at one point, that things might have been different had he lived…but why is the quote even important? Good grief.

3. January 2012 at 17:10

Scott:

“The one size fits all problem occurs because even with a 2% overall inflation target, NGDP growth will vary greatly over time in each country. The same problem occurs with 8% trend inflation.”

It would be a much smaller problem, because real wages would adjust quickly in countries where the equilibrium wage had fallen. So inflation rates would be volatile in individual countries, but real growth rates would not (unless for supply-side reasons), and unemployment would not be a big problem. Diversity in NGDP growth rates is not a major problem as long as all the growth rates are comfortably positive.

“ imagine the eurozone divided up into regions with 5 million people…forget about national boundaries…Does the ECB favor one of those 5 million people regions over another?

But national boundaries matter, because there are barriers to cross-border migration. If you’re in a currency union, it is a big advantage to be a country that makes up a large fraction of the union — and it’s a big advantage to be a region of that country, even a small one, because your workers can easily migrate to and from other sections of that country, so regions, like the country as a whole, will be reasonably stable macroeconomically, whereas smaller countries in the union won’t. Rhode Island has an advantage over Panama because it’s part of the country that makes up 100% of the official dollar zone.

3. January 2012 at 17:35

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=12122

is the disputed post in question, if anybody REALLY cares (just search for “Governor Strong” – you’ll find it.

in any case, I’m not sure about the good governance issue. it almost intuitively assumes that immigrants corrode public trust – but if you look at the nations that opened their markets freely after the 2004 wave of integration into the EU, the legendary Polish plumber didn’t wipe out the UK or Sweden. it is a bit of a tough issue to pinpoint, since few nations have had uncontrolled immigration. nevertheless, I’d submit that the lack of public trust in government around 100 years ago in large cities was perfectly justified – they provided little to no safety net (while the machines of machine politics did), police were corrupt/brutal, and immigrants had few rights. in such circumstances, if I were a poor immigrant, I doubt I’d have much faith in government either.

3. January 2012 at 18:06

Scott, Morgan

Re – Inflation and savings. Rates are effectively indexed for taxes on capital, i.e. they are fixed so that’s not a good argument. From a savers perspective, inflation should not have an impact on savings because with stable inflation you can have a sufficiently high nominal fixed rate to offset inflation and with variable inflation you can invest in floating rate instruments. Inflation does add uncertainty to the returns, but I doubt you can demonstrate whether this increases or decreases the savings rate. Bottom line, inflation has minimal impact on the savings rate in the U.S.

There are three major reasons for low savings in the U.S. – 1) the generous safety net, 2) high tax rates on capital which result in negative expected after tax returns when you have an asymmetric investment results (lots of losers and a few big winners), and 3) tax subsidies for borrowing money.

3. January 2012 at 18:10

Mike Sax,

Median income is a measure of average income as is mean income. You might want to make the distinction clearer. Also, you’re citing tax data for adjusted gross income (AGI) which is not a good measure of income.

3. January 2012 at 18:53

Mike Sax: since labour is the largest source of income, to favour “low wages” is to favour low incomes. I doubt that you will find many economists, right wing or not, who favour low incomes.

Lots of economists would like to keep unit labour costs down, as that promotes employment (and so higher incomes). If wages rises have overshot productivity growth, then a fall in real wages will allow productivity (and thus employability) to catch up. Particularly given getting increased capital investment to raise productivity is unlikely during a downturn. Indeed, very unlikely in the current downturn. (That graph indicates just how adverse the low income expectations have been on levels of investment.)

This leads into one of my ongoing annoyances: my dislike of the term ‘real wages’ since it is so very unhelpfully indeterminate. Do people mean the terms of labour (the ratio of labour costs to product prices for given firms) or terms of wages (the ratio of wages to consumer prices)? They are not the same thing. But either might be covered by “real wages”. This indeterminacy leads to things like saying economists favour “low wages” when they clearly don’t. Scott would like to raise people’s incomes: in the current circumstances, that is the point of NGDP targeting. (See once again the linked graph).

3. January 2012 at 19:13

Scott: yes and no. The Euro would tend to favour whichever Eurozone countries showed the greatest commitment to institutional adjustment. Over the period since 1945, that is clearly Germany. The PIGS countries have a long history of currency devaluation as a substitute for institutional reform. (Ireland is a different and particular case.) Depending where Germany was in its reform cycle would determine how Germany was currently doing vis a vis ECB policy; but over the longer term, the foregoing the ability to devalue your own currency would clearly most favour those who had not relied upon that as their dominant political economy strategy and had a stronger history of institutional adjustment.*

It is clear enough from comments by ECB folk that they think everyone should follow the “German” strategy. So, over the longer term, the Euro was going to be “pro-German”.

* Actually, this pattern extends way back to when the gold standard was going through its deflationary period: scroll down for English version.

3. January 2012 at 20:05

“In the long run the trend rate of inflation makes no difference; money is super-neutral.”

Isn’t the point of money illusion that people have a tendency to think of money in nominal rather than real terms, even when its irrational to do so? Doesn’t the existence of money-illusion mean that money is not super-neutral?

3. January 2012 at 20:45

Scott,

“The problem is one-size-fits-all, not a pro-German slant.”

The problem with seeing one-size-fits-all as a problem for the Euro but not for other large heterogeneous regions/countries – Russia, US, Brazil, China come to mind – is precisely the continued existence of said large countries (or even, of any country) with a single currency. I simply don’t buy the argument that the EU can’t have a single currency because every state, region, municipality?? just can’t exist without micromanaging its own currency, monetary policy, and exchange rate with the rest of the world.

Yes, there should be full mobility of labor and capital for a currency union to work ideally well, but this is never going to be fully true for labor, not even in the US, and it emphatically isn’t true for other large countries that are less liberal than the US. Mobility of capital within the EU is not an issue anyway. Mobility of labor, although it is enshrined in EU treaties, has been delayed in implementation due to protectionist tendencies and faces additional language hurdles.

But in spite of all this, consider this: countries such as Austria and Switzerland (non EU of course) already have non national populations of 15-18%, Germany has millions of Turkish workers, France millions of Algerians. Ireland attracted both capital and labor without troubles to become a “Tiger”. If jobs are able to attract labor across language and even EU barriers then I don’t see why the EU’s comparatively poorer labor mobility viz the US puts it in an impossible position viz a currency union. Not to mention that the heterogeneities in labor, wealth, what-have-you, in countries such as China and Russia, are vastly, vastly greater that within the EU. China also has language barriers. Etc etc.

Btw the converse is also true. Labor mobility isn’t even that great within single European countries. Germany has had a sickly North for years and a prosperous South. No one ever blamed the Bundesbank for that.

I am much more sympathetic to Lorenzo’s interpretation, the issue in the EU is a short run problem in that some countries used to fix their national debt and sticky wage issues by currency devaluation while some fixed them by institutional adjustment and good governance.

The very fact that Germany managed to cure itself from its high labor unit costs flies in the face of the whole sticky wage argument of course. It apparently IS possible to adjust real wages downward in a low inflation environment, even in a European welfare state, with grumbles, but without social unrest. And Germany’s welfare state really isn’t any much different from say, France’s. Neither is its ratio of GDP cycled through government.

I’ve said it before and I stick to it: the EU project has a large forward looking component. That is, certain treaties are designed to force changes that haven’t occurred yet. That makes the whole thing look like it is fumbling and stumbling, which it sure is, but in the hope to learn to walk better. One could very cheekily argue that the current situation of a tight money currency union is almost designed to force fiscal discipline and by extension, one part of good governance.

3. January 2012 at 20:48

@ Cthorm

“This was not a popular position among beltway libertarians at the time”

I think that’s the point… I did not mean to imply that there are no enlightened libertarians!

3. January 2012 at 21:09

dtoh,

How long your $100 stays $100 without “inflation adjusted investment” MATTERS.

Currency debasement MATTERS. Newly printed money enters based on the hand wave / debasement of the thieving king, don’t egghead your way into falsities.

3. January 2012 at 21:13

Far more important we see the true mind of the Fed (Greenspan finally speaking freely)…

“Alan GreenspanJanuary 3, 2012

The Tea Party tsunami and US fiscal deadlock

The failure of the “Super Committee” last year to reach a budget deal underscored the underlying wedge in US politics. The distribution of the electorate through most of the post-1945 years has been a dominant centre, slightly to the left or right of centre. This enabled legislative compromises to be reached with relative ease.

But a political tsunami has emerged out of our past in the form of the Tea Party, with its ethos reminiscent of rugged individualism and self-reliance. That was a dominant force for over a century, but has faded since the New Deal. The Tea Party has yet to obtain sufficient traction to forge majorities for new legislation. But its influence beyond its numerical strength has created an effective veto of new legislation before the current heavily Republican House of Representatives. It has so altered the distribution of votes within Republican Party’s House caucus that the party’s centre has moved closer to the Tea Party. Moreover, the heavy House Democratic losses of moderates in 2010 shifted the centre of gravity of their caucus to the left.

This has created something of a bimodal distribution leaving a much diminished centre. The Senate, although less affected by the 2010 election has not been immune from this shift. The days of Senators Pat Moynihan, Bob Dole, and Lloyd Bentsen seem a long time ago.

The emerging fight over the future of the welfare state, a paradigm without serious political challenge in eight decades, is accentuating the centre’s decline. The welfare state has run up against a brick wall of economic reality and fiscal book-keeping. Congress, having enacted increases in entitlements without visible means of funding them, is on the brink of stalemate. As studies by the International Monetary Fund have demonstrated, trying to solve significant budget deficits predominantly by raising taxes has tended to foster decline. Contractions have also occurred where spending was cut as well, but to a far smaller extent.

The only viable long-term solution appears to be a shift in federal entitlements programmes to defined contribution status. The assets of private defined benefit pension plans, confronted with the same economic forces, have already fallen from 67 per cent of private pension plans at the end of 1984 to 37 per cent at the end of last September. But the political problems of such a switch can be seen in state and local governments’ attempt to trim public defined pension plans. Public sector unions have fought mightily to avoid having their pensions shrink, as they have in the private sector.

Cutting back on benefits that are “entitled” is going to be a far harder political task than curbing federal discretionary spending. We have created a level of entitlements that will require a greater share of real resources to fulfill than the economy seems likely to be able to supply. Not only is the labour force starting to lose its most productive workers (the baby boomer generation) to retirement, but the generations scheduled to replace it will be the same individuals who in 1995, shocked us by scoring so poorly on maths and science in international competitions. America’s students had slipped badly after a long tenure at the top of the global educational ladder. The cohort of people aged 25 and younger is suffering the consequences in lower earnings and productivity when compared to earlier generations. Fortunately the statistical weight of the erosion in overall productivity growth is still quite small, but it will mount if our education system does not improve and we don’t increase immigration quotas of skilled workers.

With rising concerns about income inequalities, it is a disgrace that these quotas are protecting upper income groups from competition. Such a slowdown in productivity growth will create, with slowed population growth, Professor Gordon of Northwestern University says, “the slowest 20-year rise in real per capita GDP in American history”.

I do not pretend to be able to forecast how this will turn out, but we face a true revolution, not so much in the streets but in the fundamental choices we will have to make to secure our fiscal future. Arithmetic demands it.”

We have Greenspan and Mundell both freely admitting we’re talking about the folks in the wagon GETTING LESS.

Anyone who doesn’t admit and accept it is an outright liar or worse someone who makes their living whipping up the have-nots.

4. January 2012 at 08:04

Thanks Benny.

Andy, I’m not certain about exactly where the problem of downward wage stickiness becomes severe. I certainly agree that it’s a problem since 2008, but of course I also favor much more rapid NGDP growth. If European NGDP was 8-10 points higher right now (which it should be), the euro might look much more successful. I have an open mind on the optimal NGDP growth rate. The US got along fine with a low NGDP growth rate in the 1920s, but wages may be stickier today.

I’m not sure it’s easy for European workers to migrate within their country. That wasn’t my impression when I lived in Britain (where the unemployed stayed in the north) but I’m no expert on the subject. I certainly agree it’s relatively easy for American workers to move. But even so you don’t seem to see many unemployed men snapping up those trucking jobs available in Montana and North Dakota.

Of course even if I’m wrong it doesn’t affect my argument that the ECB is not specifically favoring Germany. Rather they are unintentionally favoring the big countries (which also include France and Italy.)

Thanks Ted, That was probably the comment.

dtoh, No, rates in America on not indexed for taxes on capital, that’s why these tax rates discourage saving.

Lorenzo, Maybe you are right, but if you had made that argument in 2005 not a single person would have believed you. The German system looked absurdly rigid at that time. And who knows, in 2015 it may look that way again. I’m not saying you are wrong (I tend to agree with you), just that these perceptions change over time. The German economists that I talked to thought ECB policy was too tight in 2005.

Andrew, At very low rates it is non-neutral, because workers are strongly opposed to nominal wage cuts, even if their real wage doesn’t fall. At higher inflation rates that’s not a big issue. But as Andy says above, we don’t know where the cutoff is. It’s usually been assumed that 2% inflation is high enough, but perhaps it’s not.

mbk, I think your comment about Switzerland is exactly right. They are doing fine, as is Sweden, Denmark, and Norway. This tells me that the euro doesn’t promote economic efficiency. I don’t doubt that with an effective ECB the euro could be made to work in the long run, so I accept much of what you have to say. But it seems to me that it’s not worth the effort, except perhaps in the core area (Germany, Benelux, France, etc.) Lots of pain, little gain.

Statsguy, First time I’ve seen libertarian opponents of immigration like Ron Paul described as “enlightened libertarians.” In my view the term better fits pro-immigration types like Brink Lindsey and Will Wilkinson.

Morgan. Not a bad speech by Greenspan.

4. January 2012 at 08:50

Scott,

Glad you agree.

I know you’ll admit the ECB says plainly that Greeks and Italians have to get less.

Mundell speaks as plainly as Greenspan.

—-

So the question is, don’t you have to admit that RATIONALLY the Fed has the same suppositions as Greenspan.

And they can’t / won’t say it outloud, but they will always form policy with those assumptions in mind.

WHY THEN, don’t you couch your NGDP discussion more completely…. in how it brings about such an endgame.

You often times like to play Chinese wall between decisions for politicians and decisions for economists… but that’s not whats really going on, so why do you fake it?

It leaves little old me to remind them all hereabouts what happens under your regime, and its not smart.

Because when Obama loses, not only will you have to publicly admit I was correct in how your policy agenda should have been achieved…

You’ll also have to start to tell the truth about what fiscal policies your end game actually promote.

You do this song-and-dance with DeKrugman about fiscal, and sure you are being more specific then you were before…

BUT say out loud, DeKrugman wants fiscal deficit spending because he wants a social safety net, not because he thinks it has a multiplier over 1.

If DeKrugman was forced to accept a Fiscal Multiplier of 0 as true, he’d still want MORE social safety net.

Until you confront this, you aren’t getting at the crux of the argument.

And after Obama loses, when you are arguing to a full boat conservative government, having gone after DeKrugman as an ideologue will make your mea culpa far less onerous.

4. January 2012 at 11:18

Morgan, you are being very unclear:

“We have Greenspan and Mundell both freely admitting we’re talking about the folks in the wagon GETTING LESS.”

We’re talking about them GETTING LESS THAN THEY HAVE PROMISED THEMSELVES.

We are NOT talking about them getting less than previous generations.

If per capita Medicare/Medicaid growth rate was cut to per capita GDP growth rate problems gone. If we baselined the cut on FY2000 fiscal budgets, we have a surplus. Likewise with defense spending.

4. January 2012 at 12:03

@Scott, W Peden & Statsguy

We all seem to be on the same page here. But I want to go a little further than what you’re suggesting Scott (“say 3 or 4 million per year, which would still leave population growth below 2%”). I don’t want any caps or quotas, but filters. If you hold an advanced degree, I want you to live and work in the US with minimal hassle. Really if you have invested in significant human capital (i.e. you have a talent) I want you to immigrate, but identifying those situations is too difficult in most cases. Thus this is my ideal immigration program:

Unlimited immigration

Applicants with a Master’s or PhD equivalent, or Patent-holders get first processing priority and a permanent visa.

All other applicants will be admitted after a background check (incl. fingerprinting, criminal record, cursory Google search, health records, employment history, and bank statement) English proficiency exam, and standardized test (in the language of their choice).

All visas issued in the second pool would be provisional, and any visa holder convicted of fraud or a violent crime would be given a deportation hearing with further entries barred.

Those who fail the English proficiency exam would be required to reapply for the visa every 3 years until they pass, after which they must renew every 5 years. Those who score exceptionally well on the standardized test would be exempt from the English proficiency rule, and would receive a 5 year visa. Any visa holder who starts a business that lasts at least 3 years(verified by tax receipts), earns an advanced degree, or is sponsored by their employer (private sector only) will receive a permanent visa.

Only permanent visa holders and their immediate family can apply for US citizenship.

It’s a little technocratic for my tastes, but I want us to have a system that rewards free enterprise, hard work, and intelligence. Even if you are in every way mediocre, you can still stay if you follow the rules. If we can get population growth of 5% annually under these criteria, great. My main concern is that we maximize our share of wealth creators and innovators.

4. January 2012 at 17:03

Stats, I do not mean to be unclear:

“We’re talking about them GETTING LESS THAN THEY HAVE PROMISED THEMSELVES.”

Is exactly right.

What we don’t have is this being admitting to by DeKrugman / Obama et al.

The secondary issue as to what they get compared to previous generations, is a throw-away, the previous generations comparably got diddly squat.

Diddly squat + 1 would satisfy your objections.

Let’s say it like this:

They are going to get a big chunk less than they promised themselves and planned for, say more than 30%, by my napkin math (historical payers to recipients) BUT also things are cheaper in man hours worked, and there are real almost immeasurable benefits to having a smart phone.

People in lower middle class today are able to live lives far better than the upper middle class of 25 years ago, so what they lose shouldn’t give us too much indigestion.

Cthorm, +1

6. January 2012 at 06:59

[…] a recent post Scott Sumner says the pro-German ECB is a myth: The ECB likes low inflation. So does Germany. That […]

9. January 2012 at 07:40

Morgan, After Obama we’ll get Romney–they guy who invented RomneyCare.

Cthorm, I think the English language proficiency issue is overrated.

9. January 2012 at 09:07

@Scott,

The English language proficiency issue is certainly overrated, but I think it’s a bigger problem in Southern California than it is in MA. Like Tyler Cowen I’m all for as many different ethnicities coming into the US as possible, mostly so I can taste their food, but there are some practicality issues that arise as well.

In Orange County we need to have ballots and election information presented in well over 20 languages (it’s a lot more in Los Angeles county). Just last year in Los Angeles there was an incident between LAPD and a Guatemalan national (who only spoke a Mayan dialect) who was shot because he was drunk in public and brandishing a knife, but couldn’t understand the orders from the police to drop the knife. Activists were demanding (with a straight face) that the LAPD be trained to communicate in these languages. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to ask for some basic level of English proficiency for long-term residents, but it really is a hot button issue.

10. January 2012 at 10:25

Cthorm, You said;

“In Orange County we need to have ballots and election information presented in well over 20 languages (it’s a lot more in Los Angeles county).”

Do they need to or do they want to? If that’s the problem, why not stop doing that?

13. January 2012 at 03:30

[…] up on a post by Scott Sumner, Christian Odendahl at The Economist pushes back on my claim that there is a German […]

16. May 2012 at 03:14

[…] cuts in corporate tax rates in 2001 and then again in 2007. Just as importantly, Germany instituted labor market reforms in the mid-2000s that reduced wage costs to levels that were once again competitive. The laggards […]