The most underpaid profession on Earth

Britmouse is back blogging with lots of interesting new posts. A short one that caught my attention discussed this story from 2010:

I saw the governor of the Bank of England [Mervyn King] last week when I was in London and he told me whoever wins this election will be out of power for a whole generation because of how tough the fiscal austerity will have to be,” Hale said in an interview on Australian TV reported by Reuters.

Of course the Conservatives were recently re-elected, and indeed slightly improved their standing because they no longer rely on support from the Liberal Democrats. BTW, I agree with this comment from Britmouse:

. . . sad to see so many true liberal voices leaving Parliament. You’ll be missed, Vince.

King headed the Bank of England in 2010. So why was his political forecast incorrect? Perhaps he thought the economy would do poorly during the period of austerity. But why would he think that? Perhaps because he’s a Keynesian, like Ben Bernanke and most other central bankers. Maybe he doesn’t believe in monetary offset.

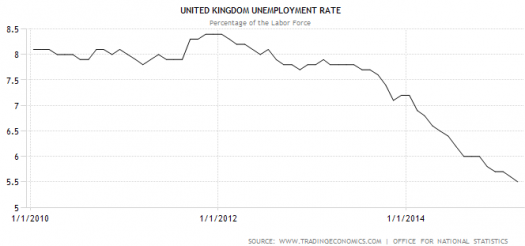

Of course there are other possibilities, maybe he thought austerity would be unpopular even if the economy did fine. But I think it more likely that he was making an implied forecast of slow growth and a weak job market. In fact growth was weak, but during 2013 the job market began improving dramatically:

Notice that British unemployment was at about 8% at the time of the May 2010 election, and still at about 7.8% in the spring of 2013. Not much progress in three years. But then the rate began falling sharply, and was at 5.5% in March, 2015, the same as the US and just slightly above Germany’s 4.9%. Total employment numbers did far better than the US. What happened? There are lots of possibilities:

1. Maybe the Keynesians are right and monetary offset was impossible in the UK. Austerity hurt. Recovery only occurred in 2013 because wage moderation finally allowed for the natural recovery forces in the economy to take hold.

2. More likely, the BoE felt additional monetary stimulus was risky, due to high inflation during 2010-13, often running at close to 4%. In that case the fiscal austerity had no impact on growth and employment, as the BoE was unwilling to tolerate higher inflation.

3. The most interesting hypothesis is that King failed to forecast that he would be replaced in 2013 by a more competent central banker, from Canada of all places. Mark Carney was appointed in late 2012, but didn’t formally join the BoE until June 2013, so it’s not quite clear where we should see his appointment impacting the economy.

Here’s Carney’s record at the Bank of Canada, from Wikipedia:

Carney’s actions as the Bank of Canada’s governor are said to have played a major role in helping Canada avoid the worst impacts of the financial crisis that began in 2007.[14][15]

The epoch-making feature of his tenure as governor remains the decision to cut the overnight rate by 50 basis points in March 2008, only one month after his appointment. While the European Central Bank delivered a rate increase in July 2008, Carney anticipated the leveraged-loan crisis would trigger global contagion. When policy rates in Canada hit the effective lower-bound, the central bank combated the crisis with the nonstandard monetary tool: the “conditional commitment” in April 2009 to hold the policy rate for at least one year, in a boost to domestic credit conditions and market confidence. Output and employment began to recover from mid-2009, in part thanks to monetary stimulus.[16] The Canadian economy outperformed those of its G7 peers during the crisis, and Canada was the first G7 nation to have both its GDP and employment recover to pre-crisis levels.

The Bank’s decision to provide substantial additional liquidity to the Canadian financial system,[17] and its unusual step of announcing a commitment to keep interest rates at their lowest possible level for one year,[18] appear to have been significant contributors to Canada’s weathering of the crisis.[19]

Canada’s risk-averse fiscal and regulatory environment is also cited as a factor. In 2009 a Newsweek columnist wrote, “Canada has done more than survive this financial crisis. The country is positively thriving in it. Canadian banks are well capitalized and poised to take advantage of opportunities that American and European banks cannot seize.”[20]

Carney earned various accolades for his leadership during the financial crisis. He was named one of the Financial Times ‘s “Fifty who will frame the way forward”,[21] and of Time Magazine ‘s “2010 Time 100”.[22] In May 2011, Reader’s Digest named him “Editor’s Choice for Most Trusted Canadian”.[23]

In October 2012, Carney was named “Central Bank Governor of the Year 2012” by the editors of Euromoney magazine.[24]

So he’s a talented central banker. But how do we know the UK wouldn’t have improved even if King had stayed on? We don’t, and indeed I think the UK would have improved, but not as fast as with Carney. Mark Carney did take some aggressive forward guidance steps in 2013, and the markets took notice. Just as in Canada, he got better job market results than his peers at other central banks. That’s not proof, but I believe the balance of evidence suggests that Carney modestly boosted the speed of the UK recovery.

Years ago I did a post arguing that central bankers are grossly underpaid, and that we should pay whatever it takes to make sure that the FOMC has people like Michael Woodford, not community bankers from Hawaii. Even if it takes a billion dollars. Of course a billion dollar salary is not politically feasible, but it’s also not necessary. Carney was reluctant to take the BoE job for family reasons, and the British government eventually lured him over with a fairly generous pay package, including that all-important London housing allowance. It did get some attention in the press, which points to the difficulty of paying central bankers their marginal product.

BTW, you might wonder why I say central bankers are the most underpaid profession. What about the President, who only makes $400,000, and yet is even more powerful and consequential? Yes, but have you checked the non-monetary compensation of being President? Even Bill Gates can’t have state dinners in the White House with a glittering international set of celebrities, or fly in Air Force One with a military escort. The total compensation of being President is plenty high enough to attract talented people. Unfortunately, the close call on whether Carney was willing to take the BoE job, and the frequency with which Federal Reserve Board members resign before their term is up, suggests that central bankers are grossly underpaid. I’ve never seen a President resign after 2 years to take a more lucrative job with Goldman Sachs.

PS. I chose Michael Woodford precisely because he is not a MM. We need to get best people possible, and this has nothing to do with whether they agree with me, or they don’t. John Taylor is another person I sometimes disagree with, who is obviously extremely well qualified for being a central banker.

PPS. Check out Britmouse’s longer new posts, which are also quite interesting.

Tags:

18. May 2015 at 09:09

“I’ve never seen a President resign after 2 years to take a more lucrative job with Goldman Sachs.”

That says to me that we have had a string of incompetent presidents that GS doesn’t want them.

18. May 2015 at 10:26

Dear Scott, I don’t see the need to be so cautious about the impact of the Carney appointment on UK growth.

Here is a speech given by Carney in December 2012, after he was selected to be BoE governor (but before he took office.):

http://www.bis.org/review/r121212e.pdf

“Our conditional commitment [in Canada] worked because it was exceptional, explicit and anchored in a highly credible inflation-targeting framework. It also worked because we “put our money where our mouths were” by extending the almost $30 billion exceptional liquidity programs we had in place for the duration of the conditional commitment. And it worked because it reached beyond central bank watchers to make a clear, simple statement directly to Canadians.

[…]

If yet further stimulus were required, the policy framework itself would likely have to be changed. For example, adopting a nominal GDP (NGDP)-level target could in many respects be more powerful than employing thresholds under flexible inflation targeting. This is because doing so would add “history dependence” to monetary policy. Under NGDP targeting, bygones are not bygones and the central bank is compelled to make up for past misses on the path of nominal GDP.”

Does it take much imagination to believe that BoE governor appointments affect the economy with long and variable leads?

18. May 2015 at 10:33

Have you been reading David Glasner’s tirades against John Taylor? The man is not qualified to be a central banker. Unless of course what he’s been espousing recently is just political posturing and he’d behave totally different when in power. Always a possibility, but what was the last intelligent or correct thing you can recall him saying?

18. May 2015 at 11:23

Simon, I agree on the policy leads, I just didn’t want to suggest that no improvement would have occurred under King. I’d prefer to understate rather than overstate my claims, given that we all suffer form confirmation bias.

If I overstate my claims then Ray might criticize me. 🙂

Policy, I don’t judge Taylor’s qualifications based on his blogging, but rather his entire career.

And yes, I’ve read David’s criticism.

I also think Stanley Fisher is highly qualified, even though he recently claimed that monetary policy has been extremely expansionary in recent years. They all say things that I regard as nuts.

18. May 2015 at 11:35

Simon:

“Does it take much imagination to believe that BoE governor appointments affect the economy with long and variable leads?”

If one believes that 99% of the public does not understand inflation, as Sumner claims, then it would take a LOT of imagination.

Also, what Carney said is not inconsistent with long and variable lags.

18. May 2015 at 11:53

King could be quite “Keynesian” about fiscal policy but quite “monetarist” as well. He had complex views.

We do know he thought the structural deficit was unreasoanbly large in 2010; if the quote is fairly attributed to him I would guess it was more a supply-side view than demand-side. i.e. it was “necessary” to reduce real government consumption, benefits, etc, in line with potential supply, and that would be unpopular. A lot of guesswork involved here.

18. May 2015 at 12:26

Taylor’s blogging might be a better indicator of his real time performance as chairman. When you are surrounded by intense pressure and criticism, a tendency to cling to your priors becomes important. His academic work is more careful, but the chairman’s seat isn’t a particularly academic role.

18. May 2015 at 14:14

Prof Sumner

What are some useful ways to think about how 1st world monetary policy treats catch-up growth in developing economies?

18. May 2015 at 14:22

Scott,

Here’s an interesting link in the weekend WSJ. It’s a book review about Richard Thaler and how behavioral economists want to upend the EMH:

“Dense with fascinating examples, each of Mr. Thaler’s topical areas tells, in a way, the same story: Traditional economics predicted X; evidence failed to confirm X and indeed often contradicted X; establishment explained away the evidence as an anomaly or miscalculation. For example, by the 1980s, investment guru Benjamin Graham’s classic, decades-old work on “value investing””””in which the goal is to find securities that are priced below their intrinsic, long-run value”””had become passé. Mr. Thaler explains that Graham’s evidence of the benefits of buying cheap stocks rather than expensive, fashionable “darlings” had become inconsistent with the Efficient Market Hypothesis, which said that value investing simply could not work””not that anyone had bothered to refute Graham’s claim empirically.”

The goal? More planning:

“Could we use behavioral economics to make the world a better place? And could we do so without confirming the deeply held suspicions of our biggest critics: that we were closet socialists, if not communists, who wanted to replace markets with bureaucrats?” Yes, he argues, and yes. Because people make predictable errors, we can create policies and rules that lower the error rate…”

I hope they fail.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/how-homo-economicus-went-extinct-1431721255

18. May 2015 at 16:21

Excellent blogging, but boy do I have a friendly disagreement with Scott Sumner on this one: Who should sit on the FOMC? Qualified economists such as Charles Plosser or John Taylor?

Give me Yogi Berra if he wants to blow a Niagara Falls of Benjamin Franklins out the Fed’s front door.

Egads, dudes. This is simple. Print more money and keep printing more until we see some honking great economic stats for a few years.

This little sissy-stuff from Janet Yellen ain’t cutting it. I am not calling for helicopter drops. I say “Send in the money-dropping B-52s.”

Actually, a holiday on FICA taxes offset by QE is a good idea.

18. May 2015 at 17:57

Benjamin Cole writes such naive, kool-aid drinker posts.

They are made all the more awkward by the “Egads” guffawing.

18. May 2015 at 18:36

Crank up the presses and print Benjamiin Franklins until the plates melt, then start issuing scrip.

By golly and sheesh, go full-tilt boogie for a couple years after the sniveling about “labor shortages” reaches a crescendo!

18. May 2015 at 18:39

@Scott,

Seriously? You could replace the entire FOMC with an iPhone application. It would be a lot cheaper and do a much better job.

18. May 2015 at 19:12

I agree with dtoh above; you could replace the FOMC with an iPhone app, or a 3% rule as Friedman wanted, and not notice the difference.

Money is neutral and superneutral in all but the very short term (hours, days) and in all rates of printing except hyperinflation (even Brazil’s 15% to 20% inflation rate over 40 years did not impact its economy negatively by more than -5%/yr).

Get over yourselves people. You are irrelevant.

18. May 2015 at 20:57

Let’s try and parse a Ray Lopez comment:

“Money is neutra and supernatural in all but the very short term (hours, days)”

Well that doesn’t really make sense, it’s either neutral or not, but let’s grant Ray the hours or days point in the meantime, for the sake of reading the sentence:

“even Brazil’s 15% to 20% inflation rate did not impact it’s economy negatively by more than -5% / yr”

Our resident genius Ray has now immediately contradicted himself, saying money isn’t neutral after 40 years. Fascinating.

The best part is that you could question him on the fact that he has obviously pulled “5%/yr” out of thin air”, our the “hours,days” point, or any other point, but you don’t need to because he can’t even write a single comment with internal consistency. Remarkable in a way.

If only you hadn’t said no to Bill Gates all those years ago Ray!

19. May 2015 at 03:38

Ben J:

Pretty sure Ray was referring to low, stable price inflation when he argued money is neutral and superneutral, and he likely was talking about statistical significance as well.

Of course I don’t agree with money being neutral over any time frame, since the economy is path dependent, but “parsing” his comment does not seem to lead to what you think.

Ray, I recommend you read Mises’ analysis of the theory of money neutrality. He showed that a neutral money is a contradiction in terms

19. May 2015 at 06:21

@MF – I read this: http://wiki.mises.org/wiki/Neutrality_of_money and while sound theoretically (different people have different values for money, hence doubling the money supply will arguably not be neutral) it fails to address how in practice statistics show money manipulation has no effect.

@Ben J – see MF’s comments, which I largely adopt. The -5%/yr is from Calomiris’ book “Fragile by Design” on the chapter on Brazil high inflation (high teens over 40 years). In other words, the “menu and shoe leather costs” of high inflation (but not hyperinflation) was only at best about a five percent drag on the economy. And towards the 1980s, when inflation really took off, the drag was even less as people adjusted (i.e., money is largely neutral). But as MF says, in times of hyperinflation money is not neutral at all.

Exercise for the reader: given today’s headline that UK inflation turned negative in April for the first time of record, comment on how this is irrelevant for society as a whole; feel free to mention the Coase theorem.

19. May 2015 at 06:38

Has this been reported here?…

“Comparing Tax and Spending Multipliers: It’s All About Controlling for Monetary Policy”

http://eml.berkeley.edu/~webfac/obstfeld/jalil.pdf

FWIW

19. May 2015 at 07:09

@Jim Glass

This is a great paper, after controlling for monetary policy, spending multipliers are insignicant and tax multipliers are large …

@Ray

I lived through that inflation, believe me, the hidden taxation is NOT the only perverse effect of inflation

19. May 2015 at 08:14

Carney has made everyone under 40 poorer by stoking the housing bubble. The UK is now in even more of a corner. So is Canada, where many are apoplectic at the obscene rise in house prices.

But of course it’s all recorded as a rise in GDP so it’s all good.

19. May 2015 at 08:49

“This slowdown was not caused by the government going back on its plans to reduce its spending. Instead it largely reflected disappointing tax receipts, caused in part by an unexpected decline in real wages. Osborne could have stuck to his original deficit reduction plan by raising taxes or cutting spending further. But he chose not to. An honest chancellor would have said that the funding crisis panic of 2010 had passed so the pace of austerity could be slowed. But to do that would have been to admit that austerity was bad for growth, and therefore that Plan A had delayed the recovery. Instead Osborne chose to bluff it out, and insist that his original plan was on track.”

http://www.lrb.co.uk/v37/n04/simon-wren-lewis/the-austerity-con

Structural deficit

And a little luck?

“One economist, Alan Clarke at Scotiabank, says the compensation payments have been more successful at stimulating the U.K. economy than quantitative easing. U.K. lenders have already paid £11.5 billion ($18.7 billion) to millions of customers, and have set aside another £7.3 billion for future payments.

But the payments are not just creating one-off windfalls: the PPI industry is also creating much-needed employment.

As we report over on WSJ.com, claims have been coming in at such a clip that it’s created tens of thousands of new jobs to handle them.”

{the PPI payments are being used as a down payment for new cars?}.

http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2013/10/04/how-a-banking-scandal-is-bolstering-britains-economy/

19. May 2015 at 09:24

@Ben

“Carney has made everyone under 40 poorer by stoking the housing bubble. The UK is now in even more of a corner. So is Canada, where many are apoplectic at the obscene rise in house prices.

But of course it’s all recorded as a rise in GDP so it’s all good.”

I always thought that the value of existing homes (even if that increase is realised when sold) is not part of GDP. So, Ben, no, it’s *not all recorded* unless the UK and Canada have a dramatically different measure of GDP than does the US.

And, if you are considering that low long-term interest rates are spiking housing prices, the Central Bank doesn’t really have much effect over those. Also, if housing prices have increased due to lower long-term interest rates, doesn’t that mean that the financing costs for those under 40 are considerably lower than they would have otherwise been? When it comes to housing and affordability, price is not everything.

19. May 2015 at 12:00

You could repeat this column with Draghi over Trichet, too. Much better, but not as good as an iphone.

19. May 2015 at 12:27

@Vivian Darkbloom

When I first read Ben’s comment I thought of the following effect: rising home prices may have a wealth effect on owners, potentially leading to more consumption from those (positive effect to AD), but it has a direct effect on those actually purchasing houses now (whose budget deteriorates with rising prices, negative to AD, because perhaps these people have budget constraints and are skipping other consumption )

19. May 2015 at 14:09

You could just as well argue that the Secretary of Agriculture is underpaid. Same for the Secretaries of the Departments of Housing, Labor, Education, Energy, and so on. It’s not that those people and those departments serve any useful purpose to merit high pay, it’s just that they are in a position to enormous damage, so we need someone smart in charge to restrain them.

Ditto for the Fed.

19. May 2015 at 14:19

@ Mike,

Maybe we should just eliminate those departments. They do tend to distort their markets anyway.

19. May 2015 at 14:28

Chuck E:

Agreed. Especially for the Fed.

19. May 2015 at 17:37

Britmouse, Do you think King anticipated that the austerity would depress growth?

A, Maybe, but I think of his academic work as best representing his real views.

Daws, Not sure I understand the question, but I’d say no effect on catch-up growth.

Anthony, I share your skepticism. What are the behavioral biases of the bureaucrats?

Benjamin, The question of who’s qualified is different from who should be chosen. There’s lots of qualified people, and I’d chose some, but not others. I wouldn’t expect Obama and Bush to chose the same people.

Ben J, I agree about Ray, and too many Bens!

Ben, You missed the point, which is that employment data is better than GDP data.

Postkey, So if slow growth in tax receipts was the problem, does that mean Osborne did not ease off on austerity, and that the cyclically adjusted deficit fell?

19. May 2015 at 17:39

Thanks Jim, That paper looks interesting.

20. May 2015 at 05:53

I’d say: ex ante he did not think it was significant demand-side drag, ex post he blamed it as one of the “headwinds” which caused weak growth.

Between May 2010 and August 2010 the BoE forecasts revised RGDP growth down by about 0.5% in 2011, and inflation up more than 1%; a fairly clear supply side shock from the VAT hike in 2011. Osborne’s first budget was June. I should write up a post on that.

20. May 2015 at 13:48

Profe Sumner

Thank you for answering. Penelope Cruz never responds to my letters.

My question was not clear because I am not sure what I mean, either. I ask because I often see politicians from developing countries complaining about “hot money”. I also wonder what domestic structural effects we can expect in countries that benefit from booming export to 1st world countries whose trade deficits grow under monetary expansion.

21. May 2015 at 05:54

Thanks Britmouse, I’m surprised to hear that he didn’t think growth would slow, he certainly left that impression to readers.

Daws, It’s impossible to know those effects without much more information. it’s not even clear that trade deficits always grow under monetary expansion (which depreciates the currency.) It might, but it depends on the circumstances.