The employment to population ratio is nearly meaningless

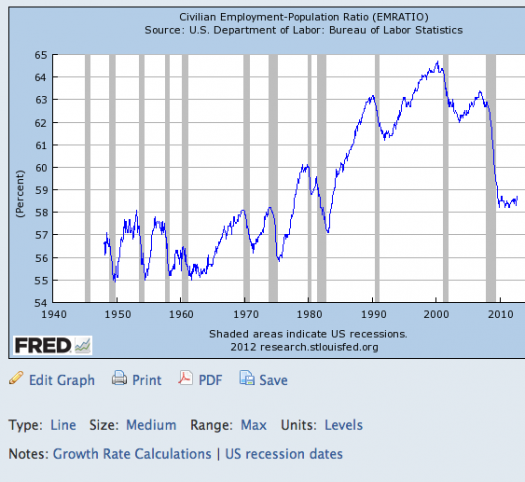

Here’s the employment to population ratio–check out the 1960s and 1970s:

Was the labor market healthier in the 1970s than the 1960s? Of course not, the opposite was clearly true. You probably couldn’t find a single macroeconomist in America who thinks our labor market was healthier in the 1970s than the 1960s. The whole idea is preposterous. And yet the employment ratio was far higher in 1978 than 1972, and higher in 1972 than 1965 (which was a boom year.)

Was the labor market healthier in 2012 2006 than 20062012? Yes, that’s obviously true. But it’s equally true that we can’t make that inference from this graph, which doesn’t tell us much of anything about the health of the labor market. The problem is that the trend employment to population ratio was sharply rising after 1964, before peaking around 2000. Now it is on a sharp downtrend. The current labor market is weak (7.8% unemployment, even more if you count part timers who want to work full time) but the graph tells us very little about that weakness.

If you look at the graph it would appear that the US labor market is not healing, which might make one skeptical of the sticky wage theory. But once one realizes that the graph does not describe the health of the labor market, and that you must look at unemployment rates, the picture changes radically. Now we see a labor market that has created 5 million jobs in recent years, where the unemployment rate has fallen from 10% to 7.8%. Indeed the only reason Obama has even a prayer of winning this election is the huge fall in unemployment in states like Ohio and Michigan. If their labor markets had not improved he’d be toast right now.

I’m not sure why the employment to population ratio is now on a downtrend. Obviously the big recent drop is partly the recession. But the trend also picks up a growing number of old people who are out of the workforce, more people on disability, a falling preference for work among upper-middle class teens, and lots of other factors. Maybe even more people in prison.

Even when the economy is fully recovered we won’t get back to the 2007 peak, and we won’t even get close to the 2000 peak. But that fact will tell us nothing about whether we have restored equilibrium in the labor market.

PS. This post is a sort of reply to a recent Tyler Cowen post. This is puzzling:

In one very real sense, there is a significant demand shortfall. Yet repairing that demand shortfall requires many building blocks. Nominal reflation (which I favor) is only one of those building blocks. The others are rooted in trust and perceived real wealth, which are both slower to repair and require different policy instruments, plus the mere passage of time.

Tyler defines “demand” differently from most macroeconomists. He doesn’t mean aggregate demand, as on an AS/AD diagram, he means something closer to quantity demanded, i.e. real output. Trust boosts AS, not AD. Trust will boost output even if the Fed targets NGDP. On the other hand a true AD factor would not boost output if the Fed targeted NGDP.

PPS. I might add that as each month goes by, and the unemployment rate falls to lower and lower levels, and 5,000,000 new jobs are created, I find it odd to see a rapid increase in blog posts that tell us why the unemployed won’t be able to find jobs, and that the problem is structural. So here’s my question–where do the structuralists think the unemployment rate is headed?

PPPS. This post should not be construed as a denial of structural problems. A significant share of the job loss reflects early retirees, disability rolls, extended UI benefits, etc. But there’s still a lot of cyclical unemployment. And more AD will lead Congress to trim back on UI.

PPPPS. And if you don’t think unemployment will fall, do you want to make a bet? (Not with me, with Bryan Caplan)

Tags:

10. October 2012 at 06:51

Judging from the job market forums I’ve been searching in many cities, the bet is that the person moving to find work will not end up homeless.

10. October 2012 at 07:13

This is kinda of noise.

The fact is if we do my GI plan and Auction the Unemployed, we’ll see 30M+ go to work, we’ll see people work till they are 75, we’ll see youth sign up for part time GI of $3 or $4.

THAT’S REAL EMPLOYMENT DEMAND.

The way we figure that out: is how many people starting at $1 per hour have a ROI found by private employer?

The fact that society pays a GI has nothing to do with it.

Imagine a world with no safety net, we’d see the 30M+ working to eat.

The GI is a social guarantee.

The Auction is the real demand for globally priced labor.

10. October 2012 at 07:18

Scott, women work now. Get over it.

That number needs to keep going up. More people out of the wagon. Less people in wagon.

The question isn’t “will we cover their nut”

The question is “will we make them work for their aid”

10. October 2012 at 07:25

Here’s a “promising” result.

http://www.indeed.com/local/Savannah-GA-jobs

“The Savannah, GA job market is strong compared to the rest of the U.S. Over the last year, job postings in Savannah, GA have declined by 18% relative to a national decline of 32%.”

I wish I had a job, plain and simple. So does everyone else so that none of us would need to be talking about any of this.

10. October 2012 at 07:37

Was the labor market healthier in the 1970s than the 1960s? Of course not, the opposite was clearly true. You probably couldn’t find a single macroeconomist in America who thinks our labor market was healthier in the 1970s than the 1960s. The whole idea is preposterous. And yet the employment ratio was far higher in 1978 than 1972, and higher in 1972 than 1965 (which was a boom year.)

That’s strange, because when I look at that chart, I see the 1970s as worse. The employment to population ratio widely fluctuated during the 1970s, falling quite substantially on at least two occasions. However during the 1960s, we see a gradual increase in the ratio, which to me signals a more healthy decade.

Are you sure you are not cherry picking? You picked one peak in the 1970s and compared it to one year in the 1960s. Maybe looking at the whole decade, the trend of each decade, is a better approach.

Are you purposefully hand-waving at this ratio because it is not an NGDP story?

The prior reference to “macro-economists” is a rather weak argument. No theory is right or wrong based on its popularity. If that were the case, then NGDP targeting theory and ABCT would both be necessarily wrong because they are not popular. We have to be willing to say that most macro-economists are wrong, just like you thought that, and probably still think that, about most macro-economists when it comes to NGDP and 2008-2009.

You have said most were wrong in the past, and yet now you’re depending on that same criteria to justify what you are saying now.

PPS. I might add that as each month goes by, and the unemployment rate falls to lower and lower levels, and 5,000,000 new jobs are created, I find it odd to see a rapid increase in blog posts that tell us why the unemployed won’t be able to find jobs, and that the problem is structural. So here’s my question-where do the structuralists think the unemployment rate is headed?

As the unemployment rate falls to lower and lower levels, structuralists do not necessarily believe that things are getting back to normal. It is more likely that the structuralists believe the Fed’s inflation has created yet another “boom”, but because the last collapse was so steep, this boom appears as a stagnation.

To answer the question, most structuralists I know believe that employment is going to go up (temporarily) if the Fed can continue to sustain the current inflationary boom, and by all accounts, it appears they are. There is no hard and fast rule that presupposes constancy in relations for this, because humans learn over time. We are not chained to constancies the way atoms and molecules are. It may be that the Fed now has to increase the money supply by 20% per year (for however long) to generate enough “spending” that keeps nominal profits up to as to prevent correction/deflation. It may be more or less than 20%. It depends on current knowledge and valuations.

What we can know a priori is that since 2008, and of course prior to that, investors and consumers have not been able to observe actual market preferences as manifested by unhampered pricing and interest rate signals, there are clusters of errors being made as we speak, that are not yet showing up as nominal losses. Investors and consumers are calculating using historically low nominal interest rates. Who knows how high the true market rates are? If they are substantially higher, then you can guess how substantial the error-making must be.

Personally, I think there is a sovereign debt / bond bubble that has been created (which has been building for decades, and investors are now going all in on sovereign debt, and with all errors that have accumulated over the decades in the US (vis a vis the rest of the world), that are now being propped up by sovereign balance sheets, I can’t see any other bubble source that can serve as the next prolongation once the state’s debt prices correct. Of course, states can print their own money, so we will probably see the next collapse consisting of central banks taking control of huge portions of capital markets that go into deflation. Who knows, they may even do this in the name of NGDP targeting.

My biggest concern is market monetarists and other inflationists considering the current times to be times of recovery back to some normalcy, or at least inherently healthy times that is capable of becoming more healthy if only the Fed would create more money according to a “superior rule”, rather than understanding the current times to be an “eye of the storm”, where the economy is so incredibly distorted and propped up by trust in government debt, that our attention is directed to seemingly more pressing issues that are only seen as such because they are more easily observable and “slap in the face” obvious, when the most important issues are what is not popular to talk about, because profits are being made and people are happy and don’t want to hear gloomy stories.

10. October 2012 at 07:47

But detrended swings in the ratio are informative about labor market conditions, right? The whole point of using the ratio instead of the U-rate is to capture discouraged workers dropping out of the labor force, perhaps going on disability. Most of the 5 million new jobs went toward making room for new entrants, didn’t they? Plus crappy part time jobs, which is sign of some adjustment…

10. October 2012 at 07:48

Morgan, I think Scott has “gotten over” the fact that women, such as his wife, work similar jobs to men.

10. October 2012 at 08:03

Is the labor market healthier in 2012 than 2006? Yes, that’s obviously true

Obviously true? I must be dumb as a brick.

10. October 2012 at 08:07

Obviously true? I must be dumb as a brick.

If we ignore the employment to population ratio, if we ignore the absolute number of all employees, if we ignore the number of people on UI and foodstamps, if we ignore the number of people who left the workforce because it is so bad, then yes, the labor market in 2012 is healthier than 2006.

(Don’t worry, you’re not dumb if you disagree with Sumner)

10. October 2012 at 08:10

Scott, I think you meant it’s obviously true that the labor market was healthier in 2006…

10. October 2012 at 08:12

The labor market moves back to full employment via two mechanisms: falling real wages and dropping potential nominal income. The latter is because of labor market hysteresis, where the marginal product of the long-term unemployed falls. I think this is the source of concern with structural unemployment: The natural rate slowly rises to meet the falling total rate.

10. October 2012 at 08:12

I don’t really buy the trust argument in Tyler’s post (what is trust, and what kind of trust was broken?), but there is an important point about multiple equilibria.

Reflation might have been enough early in the recession, but it might not be enough now. I think (I can’t seem to find the link) Paul Krugman has argued that the long-term unemployed after a while drop out of the labor force, and that to restore the labor force participation something has to happen (like, for example, WW2). Indeed the US labor force, while on a downtrend since the late 90s, seems to have accelerated the fall rate since the recession (http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=bFg).

Employment-Population ratios change as society’s preferences change (like the entrance of women into the labor force), but they could also be affected by one-time events that move the path to a different equilibrium path.

Tyler Cowen seems to imply that restoring NGDP back to the old level path will not (by itself) induce the labor market to move back to the pre-recession path.

10. October 2012 at 08:12

MF, isn’t the labor market still worse after taking all those things into account? 7.8% unemployment hello?

10. October 2012 at 08:23

Nearly meaningless? What?

So if we had 1 person working and everybody else unemployed it would be “nearly” the same as everybody working except one unemployed person?

It’s one thing to say there are other factors (like more women working over time which makes the whole “nearly meaningless” argument even sillier), but, in my opinion, you’ve come nowhere close to making the case that the ratio concept is “nearly” meaningless as a measure of economic health

10. October 2012 at 08:31

Isn’t the main feature (maybe only, since “trends” are in the eye of the beholder) of the graph that the supply of workers is cyclical? And therefore, the unemployment rate is partly a measure of unhappiness rather than a pure measure of how far the economy is from its theoretical (given a long enough uninterrupted expansion) potential.

10. October 2012 at 08:39

Suppose the nation had a population boom of new babies in, say, 1945-1947. All else equal, the employment to population ratio would fall until those babies reached working age in about 1963-1965. Then the employment to population ratio would rise merely from the population boom.

If, say, women and minorities who had previously been excluded from the workforce now had opportunities, this might cause a structural break in the employment to population ratio that would last many years.

The point is that the E-P ratio is only “worthless” when you view it in isolation over time rather than considering all the major factors affecting this ratio both temporary and permanent. In other words, the analysis or conclusions of economists who fail to hold all else constant are worthless.

The recent plunge in E-P isn’t as bad as it appears; many people who otherwise would not work were drawn into employment by an artificial boom, and now they have left. But. the percentage drop in E-P following the financial and housing bust is unprecedented in the era shown on the chart. It is indeed cause for some alarm. Explaining why it remains so low requires more detailed analysis. Labor productivity is up, there are structural adjustment problems, geographic anchoring, and government assistance as a disincentive.

10. October 2012 at 08:52

Saturos:

MF, isn’t the labor market still worse after taking all those things into account? 7.8% unemployment hello?

[Thump thump thump], is this thing on?

I am saying 2012 is worse than 2006.

Sumner said:

“Is the labor market healthier in 2012 than 2006? Yes, that’s obviously true.”

Dude…this is pretty meta.

10. October 2012 at 09:03

Scott: Krugman has written about this topic. He argues you can get a better metric by correcting the employment-population ratio for demographic shifts, specifically by segmenting the data by age and then taking a weighted average of the segments. Krugman describes it better than I just did:

=====================

So here’s an arguably better measure: constant-demography employment, which shows what would have happened to the employment-population ratio if the age structure of the population had stayed constant.

For my calculation, I’ve divided the population into three age groups, 16-24, 25-54, and 55 plus, for which employment-population ratios are available in the BLS databases. (Scroll down and use the one-screen data search). I’ve then taken a weighted average of these ratios, where the weights are the 2007 shares of each group in the civilian noninstitutional population. And here’s what you get:

=======================

See http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/06/constant-demography-employment-wonkish-but-relevant/.

It’s easy to argue this too is imperfect, but all of our measures seem to be imperfect, so we may as well improve the ones we’ve got.

===============

Kenneth Duda

10. October 2012 at 09:16

“Is the labor market healthier in 2012 than 2006?”

Is that what you meant to say Scott? Or did you switch the years?

10. October 2012 at 09:16

Yeah, I agree, that was a great post by Krugman.

10. October 2012 at 09:59

Bill McRide at Calculated Risk has written extensively on why the labor force participation rate has dropped. Short version: baby boomers retiring, more kids getting post-secondary education:

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2012/05/declining-participation-rate.html

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2012/10/employment-decline-in-participation.html

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2012/10/understanding-decline-in-participation.html

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2012/10/further-discussion-on-labor-force.html

10. October 2012 at 10:09

Considering his point only makes sense if you reverse 2012 and 2006, yes, that’s what he meant.

Scott & others, what do you make of this Marcus Nunes post?

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/10/07/due-to-the-great-recession-have-the-young-suddenly-aged-2/

Seems like demographics actually don’t have much to do with the decline in employment/population. Sure, younger people are going to school more and working less when they are in school, but that is mostly a function of the bad economy, no?

10. October 2012 at 10:09

Kenneth Duda:

Krugman stated:

“So contra Romney, this is a real recovery. Modest, but real.”

Remember, Krugman would consider the economy to be in a “real recovery” if everyone were paid by the state to dig holes in the ground, since “employment” is all that matters.

10. October 2012 at 10:31

You could make an argument for limiting this to 16-65 demographics.

Other than that the graph is totally right and you are totally wrong.

10. October 2012 at 10:52

Of course civilian employment is a terrible number to use. It doesn’t account for age at all. If you have more people become older or a lot of young people being born, this number doesn’t account for that. This statistic alone tells you very little.

10. October 2012 at 11:12

Bob, I am dumb as a brick, not you–I had the numbers reversed. It’s corrected now.

Cameron, No, lots of upper middle class kids simply don’t want to work. What happened to the paper boy? The kid who cut grass and shoveled snow? I used to do all those jobs in the early 1970s–now I rarely see kids doing that sort of work. When I ask parents why they tell me the kids are too busy with homework and extra-curricular activities.

Everyone, I agree that Krugman’s data is slightly better, but no where near good enough. There are many factors beyond age than explain the falling share of people in the workforce.

10. October 2012 at 12:01

Hey kids, let’s roll back the clock to September 13th, 2012, the day of the QE Infinity announcement. Recall this gem:

“Long term yields increased on the news, just as market monetarist’s would have expected. And thank God they did! The higher yields are an indication that markets have (slightly) raised their NGDP forecasts going forward. The jump in equity markets suggests that RGDP growth will also rise (albeit modestly.)”

Now fast forward about a month later, to today, October 10th 2012.

How are stocks doing?

Here’s the S&P 500

How about long term yields?

Here is the TNX 10 year note yield.

What happened to “the markets have raised their NGDP forecasts”? What happened to “The jump in equity prices suggests RGDP growth will also rise”? Looks to me like the markets don’t behave in the way market monetarists predict. Maybe there was a secret plan all along: to show EMH is so true, not even market monetarists can know what will happen (unless of course it does happen, in which case we are to temporarily suspend EMH and bow down to market monetarism wizardry) LOL.

10. October 2012 at 12:22

I agree that’s part of what’s going on, but did that trend suddenly intensify since 2008? To be fair, now that so many teens have stopped working (IMO partially due to a bad labor market), will they get jobs again when the economy recovers? I doubt it. The supply of labor has shifted to the left.

We are not as hardworking as we thought. 🙂

10. October 2012 at 12:33

Cameron:

We are not as hardworking as we thought.

But that’s impossible. As this chart shows:

http://i.imgur.com/a5IEs.png

The 25-54 age group got hammered the hardest, and this age group has the most debt. If their incomes fall, then their debt obligations SHOULD make them work harder. Amiright? Hello? Anyone? Bueller?

10. October 2012 at 12:57

Major Freedom, right. The 25-54 group will mostly return to work when the economy recovers. Note we are talking about employment rates, not work effort or hours. The decline accounts for roughly a 3% drop in the employment to population rate (10 million jobs/312 million people).

http://thefaintofheart.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/aging_32.png

10. October 2012 at 13:25

“No, lots of upper middle class kids simply don’t want to work. What happened to the paper boy? The kid who cut grass and shoveled snow? … When I ask parents why they tell me the kids are too busy with homework and extra-curricular activities.”

Kids are busy with homework and extra-curricular activities for good reason. I think it’s wrong to say they “simply don’t want to work.”

10. October 2012 at 13:27

Beware the graph that starts in 2005!

10. October 2012 at 13:54

‘Indeed the only reason Obama has even a prayer of winning this election is the huge fall in unemployment in states like Ohio and Michigan.’

Hmmm. That’s a long way from, ‘Stick a fork in him. Romney’s done.’

10. October 2012 at 13:57

‘Krugman stated:

‘”So contra Romney, this is a real recovery. Modest, but real.”’

The same Krugman whose book is titled, ‘End This Depression Now!’?

10. October 2012 at 13:57

As far as sticky wages go, there is not much better evidence than this article on how Wall Street pay is still going up.

http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/10/09/wall-street-pay-remains-high-even-as-jobs-shrink/?src=rechp

If there was one sector that would treat employee wages like bids at a cattle auction, it would be Wall Street. Instead of wages shifting downward, however, financial firms have cut head count considerably and cut noncompensation costs.

There is now an army of people in the New York suburbs with considerable financial experience in some product area that went out of favor and who have been unemployed or marginally employed for a long time.

Less people working in finance should happen. It probably became far too big of a sector as the global savings glut needed to find investments. But ideally salaries would fall like oil prices fall in a glut of oil. Instead, salaries have increased and there is a glut of finance workers. Many of the unemployed finance workers should have long ago changed industries, but they keep trying to get a job because a Wall Street job still has more compensation than other employment.

It’s interesting to me how, even in finance, sticky wages have so much power. It just seems to be common sense would rather send some workers off to never see again then face a bunch of pissed off employees.

10. October 2012 at 16:13

Cameron:

The 25-54 group will mostly return to work when the economy recovers.

Kind of off topic, but I’ve always found this statement to be rather tautological. Recovering economies is typically defined in terms of employment, so the statement I quoted is like saying “people will get hired when people get hired.”

10. October 2012 at 16:17

Jason:

Beware the chart that starts in 2005!

Why? The chart is intended to show what happened during and after the recent bust of the cycle.

The data prior is not relevant.

10. October 2012 at 17:01

Scott, I get your point. But while it’s true that the labor participation rate may not tell us everything, I don’t believe that it tells us nothing.

The participation rate has fell approx 5% in two years (1/1/08-1/1/10). That’s 12 million people. Is this completely explained by (your words above): “a growing number of old people who are out of the workforce, more people on disability, a falling preference for work among upper-middle class teens, and lots of other factors. Maybe even more people in prison.”? In two years time?

Doubtful.

10. October 2012 at 17:09

Becon:

Kids are busy with homework and extra-curricular activities for good reason. I think it’s wrong to say they “simply don’t want to work.”

Why? Isn’t simply not wanting to work a good reason? If a teen chooses homework and extra-curricular activities, then this is simply not wanting to work. Doing one thing implies that you simply don’t do anything else.

Question: Haven’t kids always had homework and haven’t they always engaged in extra-curricular activities? Isn’t it a little too convenient to be saying that these things suddenly skyrocketed 2008?

10. October 2012 at 18:53

Paly, I never claimed it was.

Becon, When I say they don’t want to work, what makes you think I believe they don’t want to work for no good reason? Read my posts literallty, don’t read into them.

10. October 2012 at 19:32

Scott, don’t think I can agree with you on that, the employment to population ratio (henceforth called “the ratio”) is far from meaningless.

The rise in the ratio from the 50s to 2000s reflects a more active role women play in the US economy. Women over 20s ratio has been climbing steadily from around 33% in the 50s to 60% in 2000s. Particularly, the period you mentioned, women over 20s ratio jumped from 36% in early 60s to 44% in early 70s.

That being said, notice that all the sharp falls in the ratio coincided with recessions, how do you explain that with any other theory?

“I’m not sure why the employment to population ratio is now on a downtrend. Obviously the big recent drop is partly the recession. But the trend also picks up a growing number of old people who are out of the workforce, more people on disability, a falling preference for work among upper-middle class teens, and lots of other factors. Maybe even more people in prison.”

Well, let’s take the most recent fall in the ratio as example, 90% of the fall happened sometime between March 2008 to end of 2009, if the downtrend is caused mostly by ‘real effects’, shouldn’t we expect a milder, more homogeneous decline? I would say the recent drop due ‘partly’ to recession is an understatement, it’s more like 90%.

“The current labor market is weak (7.8% unemployment, even more if you count part timers who want to work full time) but the graph tells us very little about that weakness.”

Neither does the unemployment rate, and the reason lies behind the way ‘unemployment’ is being defined and calculated by the BLS.

“And if you don’t think unemployment will fall”

You see, there’s a bunch of people who don’t have jobs, but not actively looking for jobs (hence not classified as unemployed) but would want a job if offered one, and their number has increased from around 4.5 – 5 million to 6.7 million, that’s a good 1 million plus of people which is around 1% of the labor force. If the economy starts improving significantly these people might start looking for jobs again and will be classified as ‘unemployed’ and might cause the unemployment rate to go up again though it’s not a sure thing. In fact that’s part of the reason why you saw a drop and later increase in unemployment back in 2011.

To conclude, you need to look at many employment data together to get a better picture, any single data could be highly misleading and yes that includes the unemployment rate.

10. October 2012 at 20:35

Looking at these employment ratios, I am comming to the conclusion that what matters is not the level of the ratio but the change. Looking at this data, the employment ratio was 63% in 2001 and in 2006. The labor market was healthy in 2006 and sick in 2001.

This may suggest that the way we talk about unemployment is wrong. 7% unemployment is bad if you are comming from 5% and it is acceptable if you are comming from 9%.

10. October 2012 at 22:42

If you understand its limitations, employment to population ratio is a useful indicator. Even from the graph, the labour market was “healthier” in the 1960s than 1970s since it had steady growth across the former decade and was somewhat erratic (to put it mildly) in the latter.

One can also see how calamitous “the Great Recession” was.

Like most labour statistics, it has its cyclical and its structural element. This is surprising or disabling?

10. October 2012 at 23:49

” the trend also picks up a growing number of old people who are out of the workforce, more people on disability, a falling preference for work among upper-middle class teens, and lots of other factors. Maybe even more people in prison.”

Krugman’s idea of a demography-adjusted ratio (linked by Kenneth Duda, above) would be the right way to go. BTW, the effect of people in prison is far from nontrivial. I had a go at calculating it here: http://tiny.cc/wvhccw

11. October 2012 at 02:15

The idea that “some” of the fall in employment-population ratio is due to the recession seems flatly contradicted by the fact that the graph shows the entire drop in this ratio occurred in the few short months when we were technically in recession. You can’t explain that away.

Maybe the ratio is growing slightly lower as baby boomers retire but a sudden and complete drop that doesn’t recover shows a sudden (indicating that these people are still capable of working) mass exodus from the work force.

The unsupported assumption that the employment-population ratio doesn’t tell us about the labor market is so completely contradicted by how the ratio falls during recession. I don’t see how Scott could have come to these views and I don’t think that they were adequately or even basically explained in this post.

11. October 2012 at 06:19

MF,

It could be that there have been other economic occurrences or news that have negatively impacted markets since the announcement of QE3. The Fed might expand QE3 more at the next meeting to compensate for these, might not. It is too bad they aren’t setting expectations that they will adjust their monthly activities based on occurrences that happen between meetings.

11. October 2012 at 11:12

@Morgan Warstler

The fact is if we do my GI plan and Auction the Unemployed, we’ll see 30M+ go to work, we’ll see people work till they are 75, we’ll see youth sign up for part time GI of $3 or $4.

Why is that better than a wage subsidy?

Imagine a world with no safety net, we’d see the 30M+ working to eat.

I think that it is a false assumption to think that the officially unemployed are not working. So you are probably right but the UI rate measures taxed jobs that are better than most for cash or for in home consumption jobs.

11. October 2012 at 12:29

Floccina,

“Why is that better than a wage subsidy?”

1. Because it is online, so all workers must get online to participate. Right off bat, we are raising bar on on our citizens – to get help, you MUST help yourself.

2. Now that they are online, they are thinking they gotta get that smart phone, to take pictures and document the work they are doing… to increase their payday.

3. Now we have a feedback loop, the computer takes over, finding deal hunters the babysitter who has been retained 8 weeks AND CLEANS that lives within 5 miles of you, so you can poach her away.

4. The online auction environment increases the $ paid for valuable workers, reduces the $ spent on the GI.

5. The online auction environment provides a weekly positive and negative re-enforcement loop on both workers and bidders.

6. Because only private firms / individuals can hire within 5 miles of unemployed, it benefits entrepreneurs where the unemployed live.

7. Because only private firms can hire, the public sector has VERY GOOD REASON to outsource public sector and become more productive.

8. As public sector reduces costs and improves service levels or public goods, more people like govt.

9. Since the folks who are paying the bulk GI are getting to bid on cheap labor AND seeing everyone be put to work for someone who WANTS to get something real and valuable out of their labor – they like and trust others more.

10. Ghettos are being fixed up cheap.

11. And to me the really important one, now that the 90% good employed are working, we can identify the 10% not good, and they can altered. They no longer have the 90% to hide in. They can be suspended for GI after X number of consecutive job failings (not being hired back, complaints, etc.) BUT the system is super forgiving, you get kicked off GI, for 6 weeks your working friend and family are PISSED at you for not working / couch surfing, and now back on week 1, just just need to get rehired and BANG you are increasing your pay again. The feedback loop alters people, makes them all work harder, be less forgiving of the lazy.

11. October 2012 at 18:28

Ed, Thanks, great link.

Everyone. I agree that sudden changes reflect cyclical factors, I meant that to compare the level today to 2006 or 2000 is almost meaningless

11. October 2012 at 19:06

Jason Ødegaard:

It could be that there have been other economic occurrences or news that have negatively impacted markets since the announcement of QE3. The Fed might expand QE3 more at the next meeting to compensate for these, might not. It is too bad they aren’t setting expectations that they will adjust their monthly activities based on occurrences that happen between meetings.

For sure, and using that same logic, going back to the initial jump in yields right after QE3 was announced, could have been caused by something other than a changed NGDP expectation.

16. October 2012 at 06:55

[…] got a lot of push back from an earlier post where I claimed the employment to population ratio is not reliable. Here’s the data from […]