The dog that did not bark

Tyler Cowen has a new post offering opinions on a wide range of issues. In many cases I agree with his views. For instance, this one:

5. We are still in the great stagnation, for the most part. But with nominal gdp well, well above its pre-crash peak, it is not demand-based “secular stagnation.” It just isn’t, I don’t know how else to put it. And the liquidity trap is still irrelevant and has been since about 2009.

The reasoning used is not very persuasive. Could you imagine him making that argument in late 1982, when NGDP was above the pre-recession peak? But Tyler’s conclusion seems sound.

However I take issue with this claim:

4. During the upward phase of the recovery, monetary policy just doesn’t matter that much.

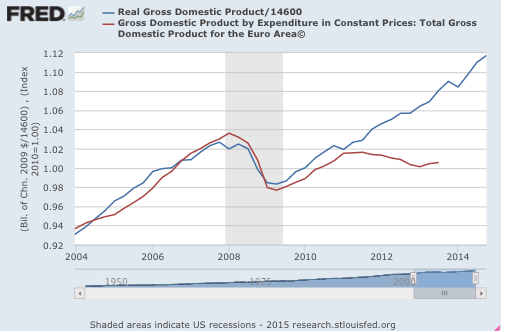

I can’t even imagine what a model would look like where that claim was true. To see why it is not true, compare the post mid-2009 recoveries in the US and Europe. If monetary policy in the US and Europe did not matter very much during the recovery, then the tightening of monetary policy in mid-2011 in the eurozone ought to have had little effect. What does it look like to you?

I think the problem here is that the US recovery looks fairly smooth, and also disappointing, despite various actions by the Fed. It’s tempting to conclude that Fed policy didn’t matter very much. But all you have to do is to look across the pond and you’ll see that it mattered a great deal.

PS. I’m not sure why the Fred’s eurozone RGDP data is not updated. I believe there’s been a very anemic recovery in the past year.

Update: Marcus Nunes has updated the graph. David Beckworth also has a post, which takes a deeper look at the US/eurozone divergence.

Tags:

25. February 2015 at 07:42

Cowen: 1 – Sumner: 0. Check and mate by the chess master TC.

USA != EU (not equal to). Structural factors, not money, which as TC says is neutral in the upward phase (and I would go further and say it is neutral at nearly all times, except when there is hyperinflation), is responsible for the divergent behaviors of the USA and the EU.

25. February 2015 at 08:19

@Ray:

Citation needed? Why would structural factors only begin mattering after this particular recession, when prior to the 2009-11 period the real GDPs of both the Eurozone and United States were steadily increasing?

“Structural factors” might account for the quantitatively different rates of GDP increase, but the post-recession divergence is a qualitatively different phenomenon.

25. February 2015 at 08:30

Scott, I was surprised by Tyler’s claim too. I am not sure what he meant by “monetary policy did not matter from 2009-2014”. Does he mean that overall US economic performance (say, NGDP growth) over that period would have been about the same even if the Fed had maintained a Fed Funds target of 20% throughout the period? Or does he mean that the Taylor rule (without QE) would have given us the same NGDP growth performance?

I did not really know how to respond to Tyler’s claim because I was not sure it was coherent. Surely a sufficiently bad monetary policy (say, a commitment to double the monetary base each month until it reaches infinity) would have made things a lot worse. How could monetary policy ever “not matter”?

-Ken

Kenneth Duda

Menlo Park, CA

25. February 2015 at 09:04

Ray, Oh, I forget, a tornado of “structural problems” suddenly hit the eurozone in mid-2011, just as the ECB announced it was tightening policy to reduce inflation. What a coincidence!

And by the way, NGDP growth and inflation also slowed, a pattern that structural problems cannot explain.

Ken, I can’t speak for Tyler, but perhaps he meant variation in monetary policies of the sort you see in real world developed country central banks. Which is why I thought the eurozone comparison was appropriate.

25. February 2015 at 09:17

Many differences between Europe and the U.S.

Also, was montery policy the same in Europe and U.S. when the lines were running together.

…

I thought the CW on Europe v. US was that the Americans did a much better job deleveraging and improving the health of their banking system post-2009.

25. February 2015 at 09:43

Mr. Sumner, please clarify, do you believe that monetary policy was the sole cause of 2+ years of stagnation of Europe’s GDP ? Isn’t that a stretch ? Let’s say you had to come up not with just one, but with three possible explanations for the gap, what would be second and third possible causes, in order of importance, in your view ? Thanks in advance.

25. February 2015 at 09:44

@Majromax–economies behave differently during recessions–that’s when the problems appear, or as Buffet has colorfully said, the swimmers that are swimming naked become manifest when the tide runs low.

@Duda– Dude, you are backing the wrong horse. Time to switch your allegiance to Tyler Cowen…

@ssumner – why do you have to lie to make your case? The ECB has NOT in fact tightened, except for a brief (3 month) period in late 2011, see http://www.tradingeconomics.com/euro-area/interest-rate (pick any time period from the drop-down box, and note interest rates since 2008 have trended downwards, except briefly in late 2011, and are at all time lows today). BTW since money is neutral, this means nothing to me, but I’m using your own ‘logic’ against you. The underperformance in the EU is due to structural factors such as the immobility of labor in the EU, as is well known, and aging demographics that caused workers to retire early when adversity struck in 2008, as I stated to Majromax above. Any other inference you draw from the data is indeed coincidence, especially if you base the divergence on a three month temporary tightening in 2011 (that was quickly reversed). Data mining at its worse.

25. February 2015 at 10:11

@Ray:

I marvel at your ability to read so much and absorb so litte.

If prices are sticky, then money is not neutral. And prices (especially wages) are in fact sticky.

http://www.motherjones.com/files/images/blog_sticky_wages.jpg

(wage changes in 2011)

Any questions?

25. February 2015 at 10:20

Ray, So interest rates are a reliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy?

What are interest rates like in countries with hyperinflation? Is money “tight”

25. February 2015 at 10:26

Jose, I suppose you could come up with supply-side explanations, but monetary policy seems like the most logical. After all, money was obviously quite tight, and the slowdown was sudden. Structural problem generally occur very gradually over time, unless there is a huge natural disaster. Also note that growth slowed throughout the eurozone–why would structural factors have affected all countries?

25. February 2015 at 10:45

“During the upward phase of the recovery, monetary policy just doesn’t matter that much.”

So far, it does not seem that anyone here is focusing on the phrase *upward phase of the recovery” (despite the obvious question—when is a “recovery” not in an “upward phase”?) So, my guess is that he would think monetary policy is still important in Europe because they are not in the “upward phase” of their “recovery”, whatever that may mean; but, I’m guessing the story of Europe as reflected in the above graph does not meet that definition.

25. February 2015 at 10:59

Prof. Sumner,

I think you should include the U.K. in your analysis (along with the U.S. and Eurozone).

http://www.aei.org/publication/qe-work-yeah-right-acknowledge

25. February 2015 at 11:10

“What are interest rates like in countries with hyperinflation? Is money “tight””

This is part of what gets me. It appears that if a country raises rates much higher than its actual growth, the only way they can meet payments without significant cuts or higher taxes (political no no), is to print it.

So it appears that at some point uber high interest rates and loose money seem to be skipping down the street holding hands with one another. How can Brasil, in a recession(?), pay 13% spot rates? Print!

25. February 2015 at 11:24

Scott, just a question to you personally, but how much impact do you actually think the state of credit/financial intermediation has on the economy?

You’ve made the case–very well, too–that the ‘creditist’ view of the economy is not correct and that demand is key, hence monetary policy can remedy it. However, assuming the activity of financial intermediaries was depressed for whatever reason, just how much impact do you think it has on the economy?

25. February 2015 at 11:41

“economies behave differently during recessions-that’s when the problems appear, or as Buffet has colorfully said, the swimmers that are swimming naked become manifest when the tide runs low.”

@Ray Blowpez

Did you even look at the graph before you wrote this. The problem didnt appear during the recession, it appeared in 2011. The tide was damn near back to to where it had started at that point. How come we didnt notice the swimmers were naked in 2008-2010?

25. February 2015 at 13:29

We’ve been through this. Monetary policy differences are not a compelling explanation of divergence between the US and Europe from 2011.

I have written a post specifically on this topic, and we’ve discussed it before.

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/10/17/did-the-ecb-tank-the-euro-zone

25. February 2015 at 14:31

@Steven Kopits: You’re focused far too much on concrete steps, rather than on expectations (which causes the bulk of the impact of monetary policy). You “question whether a 50 basis point interest rate bump is sufficient to send a continent into a three year downturn“. It’s not the 50 basis points which causes the downturn. It’s what it says about ECB decision-making, that they would think it was a good idea to raise rates at that time, given those economic conditions. That essentially sets up a monetary policy framework, a framework which suggests (correctly!) depressed demand for years to come.

25. February 2015 at 14:46

@Derivs: “if a country raises rates much higher than its actual growth, the only way they can meet payments … is to print it. … How can Brasil, in a recession(?), pay 13% spot rates? Print!”

You’ve got causality backwards. The loose monetary policy comes first, and that is what causes the high interest rates (via the Fisher effect).

25. February 2015 at 14:55

Vivian, Do you really think Tyler would claim that monetary policy does not cause RGDP to fall when RGDP is rising? That’s true, but it’s a tautology. I am pretty sure he was trying to make a meaningful claim.

In any case, wasn’t the eurozone in the “upward phase” before the ECB tightened.

Ashton, That would be a real factor, leading to surprisingly slow RGDP growth for any given NGDP growth rate. It might have been a factor, but I doubt it was the main factor.

Steven, Yes, I recall discussing this with you before. I recall you argued that money was easy in 2012 because the ECB was cutting rates. And I recall not being impressed with that argument, to put it mildly. Aren’t falling rates the long run effect of tight money (which occurred in 2011?)

And I’d add that the size of the interest rate increase in 2011 has no bearing on how contractionary the policy was. Ben Bernanke says you want to look at NGDP growth to find the stance of policy.

25. February 2015 at 15:00

Once again, Tyler Cowen says dumb things.

Quite unusual for such a bright intellect.

25. February 2015 at 16:08

Well…if the Fed acted in an expansionary manner—reintroduced quantitative easing at $50 billion a month—and that resulted in larger NGDP and RGDP without much inflation, who is to say that this is not a weak aggregate demand economy?

The Fed should try shooting for robust growth, instead of the minimum amount to avoid deflation.

25. February 2015 at 19:04

There is no point on any curve where bad monetary policy cannot make things worse.

25. February 2015 at 19:07

Ken — I guess the friendly reading is “nothing we did vis a vis monetary policy 2009-14 mattered much.” That could just mean we didn’t have very good monetary policy.

Vivian — Just for fun, I like to consider the case where the Fed suddenly adopts a -20% inflation target.

25. February 2015 at 19:51

Thank you, Mr. Sumner, but taking a New Keynesian point of view, do you believe that continued monetary easing would revert expectations at that specific point in time, meaning, with a looming sovereign debt crisis, would a strong commitment to easing revert expectations to the point of taking the whole economy from stagnation? My point is, would belief that there would be further easing, revert a series of (not so) small things that went into building expectations on investors at that specific point in time, given the Eurozone setup ?

25. February 2015 at 22:42

@SG – “If prices are sticky, then money is not neutral. And prices (especially wages) are in fact sticky.” [cites a simplistic graphic from Mother Jones] see Robert Gordon’s paper from the 80s, but still good now: http://www.nber.org/papers/w0847 (“The results for the U.K. and Japan com- pound the conflict with Okun’s analysis, since in these two countries wages have been far from sticky, even in postwar years. Prices and wages were particularly flexible in the U.S. during World War I and its aftermath, in Japan since 1914, and in the U.K. since the mid-1950s”). Any questions?

@Student – see the response by Steven Kopits, directed to you, which I adopt. Further, 2011 was not recovery. Further, indeed as if almost to spite Sumner, I would argue that the divergence could not only be due to structural factors but also coincidence. Economics is nonlinear and such things happen.

@Don Geddis – there you go again, relying on a hand-waving ‘expectations’ argument. Metaphysics. And the Fisher hypothesis assumes, at its core, that money is neutral, I hope you see that.

@ssumner – “Ray, So interest rates are a reliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy?” and “What are interest rates like in countries with hyperinflation? Is money “tight”[?]” – these are loaded questions. If money is neutral, then ‘stance’ is irrelevant. Indeed you, not I, are the expert on what is monetary policy stance by a central bank, and whether money is ‘tight’ or not. Those are monetarist questions. But, just to take a stab at it, I would say interest rates are a reliable indicator of ‘stance’ and ‘tight’ money if these interest rates are set in a free market, and the relationship is: in a free market (black market or otherwise) if interest rates are less than inflation, as often results in repressed savings economies, then money is ‘loose’, otherwise, not. In hyperinflation, interest rates become meaningless as inflation changes too much for savers to anticipate.

25. February 2015 at 22:56

I honestly don’t know what’s worse – Ray’s stupidity, or the people who try to talk to him as if he was capable of basic logic.

26. February 2015 at 04:19

@Ray – I’m glad to see you’ve narrowed your claim from “money is non-neutral” to money was non-neutral in the US in WWI.

@Daniel – I know I know, don’t feed the troll.

26. February 2015 at 04:47

“You’ve got causality backwards. The loose monetary policy comes first, and that is what causes the high interest rates”

Don, thank you for the response. My question is not which causes which. My question is how does a country, in recession, already running deficits, raise rates, and pay for it, without printing it and therefore furthering loose monetary policy? It appears self perpetuating.

As for the Fischer effect, you will never hear me use the term ‘real’ interest rates for a reason. Same reason I would never assume expected inflation to be a single point. Expectation is a distribution around a point, not a single point. Single point expected return using Beta is equally idiotic and illustrates a complete mis-understanding of volatility.

Much the same argument of asset pricing. I can sell you something today at $100, with you paying me $100 in 6 months, if rates are 0%. If you tell me rates just went to 20% per annum, I now need you to pay me $110 in 6 months (I ignore compounding in examples). Again, your raising rates appears to be perpetuating inflation. It’s not an argument of who/what started it, it’s a question of are you perpetuating it?

@Ray “In hyperinflation, interest rates become meaningless as inflation changes too much for savers to anticipate.”

I played with this once as a bettor/game theory issue. At some point forward projections must move away from historical mean reversion expectations and move to an anticipatory forward projection model, and then, as you say, expectations become too difficult to anticipate. It becomes just a highly unstable guesstimate.

26. February 2015 at 05:26

If a 50 bps rate hike — from very, very low to just very low — is going to crater your economy, then it has other problems.

If we’re in a state here in the U.S., in which any rate hike is going to derail economic growth … again, we have problems. Let’s address those problems and stop thinking the central bank can save us.

Personally I think these rate hikes and expectations of rate hikes are a very small factor in real growth, and are not clearly understood. Low rates could even be hindering economic growth.

If you had told people 20 years ago that rates would be where they are today, their models would have showed an epic stimulus. They still believe in the magic or rate moves or guidance.

26. February 2015 at 05:36

Scott, did you see that Pat Toomey (R-PA) asked Janet Yellen about interest on excess reserves– and the Fed’s plan to increase it, not decrease it? Yellen replied that “Well, remember that first of all, we will be paying banks rates that are comparable to those that they can earn in the marketplace, so those payments don’t involve subsidies to banks.” That seems a bit dubious to me (IOR seems higher than the marketplace rate, otherwise banks wouldn’t maintain the “excess” reserves at such a high level.)

Raising interest on excess reservers seems like a particularly odd way to tighten money, but I am not a monetary economist.

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/yellen-slipped-this-dubious-statement-by-congress-tuesday-204257409.html

26. February 2015 at 05:38

If monetary policy can’t accomplish real growth, how do we explain the 20% real expansion of U.S. GDP from 1976 to 1979 following the 1974-5 recession?

1976 5.4% real GDP growth

1977 4.6

1978 5.6

1979 3.1

1. Jimmy Carter was elected President and animal sprits exploded–the business class was reinvigorated, and stormed ahead! Those wimpy speeches and cardigan sweaters…

2. The (94th Congress (1976), both houses ruled by Donks, swept away years of GOP structural impediments in fell swoops, and GDP exploded! House Speaker Carl Albert to the rescue!

or…

3. Fed Chair Arthur Burns printed a lot of money, a way lot. The nominal GDP expanded by 50% from Q1 1976 ($1,824.50 trillion) to Q4 1979 ($2730.7 trillion).

Yes, the inflation rate hit an annual average of 9% as measured by the PCE in 1979. We saw double digit inflation in the early 1980s, on the CPI—then Volcker took over.

PS there is just the slightest truth in some structural reforms helping matters. The Carterites deregged transportation. I forget if they did the telecommunications and financial industries too. Labor lost ground, as it had been and did thereafter.

But seriously folks–you have to be in dogmatic, ideological, ossified, encrusted, myopic, pseudo-religious sado-monetaristic denial to say that monetary expansionism does not work.

The real question is, with inflation dying on the vine, how much real GDP growth did the Fed forego by its feeble, defeatist, wimpy monetary policy?

26. February 2015 at 06:00

Benjamin,

I don’t see the point of getting so riled up over an idiot’s ramblings.

In other news, Ray’s pen-name is used as an insult over at Marginal Revolution

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/02/knausgaard-does-america-the-new-tocqueville-but-for-the-nytimes.html#comment-158451879

26. February 2015 at 07:01

Daniel–

I know…but Ray is actually smarter than Richard Fisher or Charles Plosser…

26. February 2015 at 07:14

Ray is actually smarter than Richard Fisher or Charles Plosser

That’s a rather low hurdle to clear.

26. February 2015 at 08:20

Jose, Monetary stimulus would solve the eurozone’s demand-side problem, but not its supply-side problem.

Ray, So if interest rates are 15% and inflation is 13% then money is not “loose?”

John, I agree, I don’t like IOR.

26. February 2015 at 08:28

@SG – you did not read the Gordon paper. It does not say wages are not sticky in WWI USA only–but throughout the 20th century, for all countries examined, even in “employee for life” countries like Japan. Reason (Gordon speculates): unions outside the USA are much more willing to compromise with management on labor costs. In the USA, where there’s more ‘short term thinking’, wages are slightly more sticky. But regardless, slightly more sticky is not Okum’s ‘sticky wages’.

@benjamin cole–I know you’re only trolling, but in fact the Fed follows the market. This was true during the Volcker era as well as the Burns era. And indeed growth in the 60s was greater than growth in the 70s, which in turn was greater than the 80s, and the 90s matched and exceeded the 80s only to fall to the 00s, due to structural reasons, as you say yourself for the 70s, not due to printing money. If printing money cured economies, Zimbabwe would be a powerhouse, as would North Korea (which counterfeits US dollars among other currencies).

26. February 2015 at 08:32

Don –

You can’t put a continent into a three year recession because of expectations related to a 50 bp rate increase reversed in six months. No way, no how.

The data shows clearly that there was a crypto recession in the US at the same (and the reason for ECRI’s still not disavowed recession call at the time). I’ll do a post on this when I get a chance.

I can show you secular stagnation on an oil chart to make it easier to understand. But right now, I have other fish to fry.

Also, note in the incoming GDP data: Europe recovering, Japan (Japan!) at 2.2%; India at 7.5%. One quarter of cheap oil, and that’s what you get. No need for NGDP targeting. Just give the economy cheap oil, and things return to normal.

Now, that Greece piece, that’s even more important. At least two orders of magnitude more important than NGDP targeting. An order of magnitude more important than oil (over the longer run, assuming we still have at least some decent oil production). That’s what we should be discussing.

Meanwhile, here’s my latest article from today’s National in the UAE.

http://www.thenational.ae/business/energy/oil-on-the-turn-as-us-shale-firms-cut-back-spending#full

26. February 2015 at 08:36

@Sumner: “Ray, So if interest rates are 15% and inflation is 13% then money is not “loose?” – Yes, it’s not loose says I. And says you? I are waiting with baited breath, as your proposals are so like a chameleon.

BTW, since I think economies are nonlinear, I actually do favor NGDPLT as a placebo remedy during extreme distress. During such times, a ‘bank holiday’ (placebo), ‘fireside chat’ (Id), ‘make work’ (NRA, Id) and other such psychological ploys may ‘work’ to reboot the economy, including going to war (Nazi Germany’s war economy, which BTW you’ll be pleased to know was inflationary too). But like rebooting your computer, it’s not something that works reliably, and certainly not a cure to present structural problems in the USA such as demographic and Great Stagnation productivity challenges.

26. February 2015 at 08:46

Just to be clear: I am not against NGDP targeting. I think it can be helpful, but tricky, because policy can be tightening or loosening without an active step by the central bank.

Thus, it’s like flying at 35,000 ft and flying across the Himalayas. At that point, the altitude is ‘too low’, monetary policy is too tight. On the other hand, when you finally reach the ocean, monetary policy is ‘too loose’ and you’re flying too high. But all the time you’ve been flying at 35,000 ft. That’s how I understand NGDP and monetary policy.

To make NGDP useful, therefore, there’s a huge premium put on knowing how far the ground is below you, not only at present, but in the future. Hence, Scott’s interest in an NGDP futures market, if I understand the notion correctly. I don’t have a problem with that–it’s another tool in the toolkit. But it’s hard to make it sufficiently forward-looking, unless you have a lot of confidence in the futures market values.

As someone who spends a great deal of time in oil futures, one of the most liquid (excuse the pun) markets in the world, I can assure you that I have limited confidence in futures as an accurate predictor of prices, particularly in times of transition (eg, as the ground is falling away in front of you).

So, I’m all for NGDP targeting, but I think it is neither a universal nor fool-proof tool.

On the other hand, a Fiscal Accountability Act along the lines I outline in the Greece piece, that’s huge. Just incredibly important. That will change the entire notion of governance. In effect, it would professionalize politics, and in doing so, professionalize macro economics.

26. February 2015 at 08:56

Steven Please, interest rates tell us nothing about the stance of monetary policy. At best they might tell us a bit about the central banks intentions. But you are flat out wrong. You can create the greatest depression that ever happened with a 1 basis point rise in rates. You don’t seem to understand that interest rates do NOT describe the stance of monetary policy. They just don’t. Period, end of story.

Suppose you turn your steering wheel a tiny bit to the left, and hold it there–so your car wheels are slightly turned. How far off course will you be after 60 miles? You could easily be 30 miles off course, and that’s with just a one millimeter move in the steering wheel.

26. February 2015 at 08:59

Ray, Not loose? Again, you’ll have to tell me if you are joking. I’m a little slow.

Inflation is 13%, real interest rates are 2%, and money is not loose?

26. February 2015 at 09:38

@ssumner – please, you’re killing me with suspense. I’ve told you my answer twice. It’s 1:35 AM here in Manila and bedtime for me. So I eagerly await your answer…I say not loose, since inflation is decoupled from real interest rates (ask Don G, it’s called the Fisher hypothesis), and nominal rates > inflation, so not loose. What say you? I guess you think it’s loose since the margin between real and nominal rates is so big? You are a fan of nominal rates, since you believe in sticky wages and prices, and in the “money illusion” (apt blog title too)? People are fooled by nominal, not real, changes? Sucker born every minute? Behavioral economics? Is that it? Please elucidate us ignoramuses.

26. February 2015 at 10:02

Does Ray really work at a car wash? Not that it’s related to whether he actually works at a car wash, but he has turned out to be a complete embarrassment. I was wrong and I owe Sumner an apology.

26. February 2015 at 10:17

[…] discussing claims by Tyler Cowen, Scott Sumner […]

26. February 2015 at 10:23

Dr. Sumner,

Perhaps what Pr. Cowen meant to say was that “During the upward phase of the recovery, monetary policy just *has not historically mattered* that much”.

I believe that you are correct that monetary policy in the current recovery has been very important. In the 1980’s mortgage rates were at an all time high [1] but housing booms still formed [2]. The Federal Funds Rate was at its lowest level in January of 2003 at 0.98% and increased every month until February of 2007 at 5.26% [3]. In other words, the Federal Funds Rate, and mortgage rates, increased throughout the Housing Bubble period and that did not inhibit growth in general or in the housing market in particular at all.

It is just a guess as Pr. Cowen did not really explain his thinking in the linked blog.

[1] http://bit.ly/1ztBuK2

[2] http://nyti.ms/1vWKfWT

[3] http://bit.ly/16R6nGi.

26. February 2015 at 10:38

Yes, Scott. I understand that interest rates of themselves do not tell us about the tightness of lack thereof of monetary policy.

Therefore, it seems to me that your basic analytical chart, the one you would regularly use, presents Actual NGDP versus Target NGDP. That’s the principle measure of tightness of looseness. However, since Target NGDP is ostensibly constant (call it 4-5% per annum growth), the variable part of the equation is the development of NGDP below it. Therefore, you’re topography tracking, as such.

The skill then is in i) tracking NGDP in a real time or forward-looking way, and ii) relating that to actual modifications of interest rates, because, as I understand it, the tool you’re using to influence NGDP is the interest (eg discount, Fed funds) rate, no?

Do I have that right?

26. February 2015 at 11:02

Scott –

Have you actually made an NGDP versus Target NGDP graph?

I just did. Here’s what it looks like (2000 = base year):

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2015/2/26/actual-and-target-ngdp-5-growth

Virtually indistinguishable from a potential GDP analysis.

26. February 2015 at 11:40

And here’s the Euro Zone (Euro 18). If you think monetary policy caused this, let me disagree.

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2015/2/26/euro-18-ngdp-actual-and-target-at-5-growth

26. February 2015 at 12:23

And here are NGDP actual and target, US and Euro area, quarter on previous quarter, at annualized rates.

It paints a more sympathetic picture of NGDP targeting.

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2015/2/26/us-and-euro-target-and-annual-ngdp-growth-rates

26. February 2015 at 12:34

@Steven Kopits: “the tool you’re using to influence NGDP is the interest rate, no?”

No, not the interest rate. The tool is simple OMOs (or possibly transactions on an NGDP futures market), i.e. changes in the monetary base. Whatever interest rate results is determined by market forces, and not tracked or managed by the central bank.

26. February 2015 at 12:36

Possibly, Don. Then you have to link OMOs to NGDP. But I think NGDP targeting is agnostic about the tools. But whichever tools you use, you have to have some feel for how they translate into NGDP.

26. February 2015 at 13:52

Ray, Loose, obviously.

Bonnie, No need to apologize, he’s been hugely entertaining. Everyone loves a clown.

David, Yes, that’s what I thought he meant, and I think it’s wrong.

Steven, You say you disagree, but don’t tell me why.

26. February 2015 at 14:34

So, Scott, open up the link to the second graph, here:

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/10/17/did-the-ecb-tank-the-euro-zone

From Q2 2009 to Q2 2011, Fed policy and ECB policy largely mirrored each other. The discount rate was essentially steady in both cases. The US did see QE2 in 2010, but the Fed itself dismissed this initiative as essentially meaningless in terms of GDP impact.

Now, after Q2 2011, US and Euro Zone GDPs start to diverge from each other. The only material change in policy during this period is the 50 bp interest rate rise the Euro discount rate, which was quickly reversed.

Agree so far?

Nevertheless, US GDP continued to rise, and Europe sank back into recession.

There are thus three possible explanations for this outcome.

First, the ECB tanked the Euro Zone. A 50 bp move is not very large, but I could spot you a six month downturn if you wanted to push me on the matter? But a three year downturn, one of near record length? Out of the question.

Second, some unique demand or supply shock could have hit the Euro Zone, but spared the US, during this period. Certainly there were problems with the PIGS, but I don’t recall Q2 2011 as a particularly bad stretch in the matter. We’re looking for a turning point at Q2, and I don’t think the PIGS qualify. They were an on-going chronic problem at the time, but no worse than they had been, say, the year before, as I recall. Indeed, it was the US, with the government shut down crisis, that was suffering from “policy uncertainty” (per Prof. Chinn).

The third possible explanation is that both the US and the Euro Zone were subject to an external shock, but the US proved more resilient.

And we do in fact have an external shock in Q2 2011–the Arab Spring and the associated oil price spike. This spike, by traditional standards, should have been enough to send the OECD countries into recession, and with the exception of the US, it pretty much did.

So then why did the US escape? Well, if oil was the scarce commodity and the driver of the downturn, then a country suddenly producing a lot more oil might have been spared. And lo!, the US did and was. This shows up very markedly in the current account. The Europeans were required to adjust their current accounts by reducing oil consumption; the US adjusted by reducing oil imports, but consumption, less so. Thus, the US to a certain extent was able to avoid the oil shock and resume growth, even if tentatively.

This explanation is straight-forward and makes sense. It corresponds to major events we can document and remember. And it explains why the US has been the envy of the world for the last year or so–we’re producing ungodly amounts of shale oil and its really improving our current account.

If we believe this model, then the collapse of oil prices should i) lead to a recovery of growth in other OECD countries, which we are seeing (Japan, 2.2%); ii) increase the pace of growth in the non-OECD countries, to wit, India at 7.5%; iii) we should see a surge in global oil consumption, which we are also beginning to see. Just as the IMF, World Bank and others have been over-forecasting GDP, with this reversal, we would expect GDP to out-perform their expectations. And it is.

So, if you put the recent recession down as an oil shock, then it all makes sense, right down to the secular stagnation. I’ll publish a graph on that later.

26. February 2015 at 16:05

“we should see a surge in global oil consumption, which we are also beginning to see.”

Steven, you’re scaring me. I’m short it. 🙂

26. February 2015 at 17:41

Sumner:

“Ray, loose, obviously”.

Hahaha, now Sumner is reasoning from interest rates.

Sumner switches back and forth and contradicts himself all the time on this. He desperately wants to convince people the absolutist belief that “high” interest rates tell us something about money printing, but then we’re not supposed to reason from interest rate changes.

If interest rates are 15% and price inflation is 13%, then these facts are consistent with unchanged NGDP growth, which in the long run is neither loose nor tight in Sumnerese.

Price inflation being less than nominal interest rates, and the level of nominal interest rates, don’t tell us anything of the stance of monetary policy. Any claim to the contrary are ad hoc conveniences, much like people deferring to the convenient ad hoc fact that “most people agree with me on this” to strengthen their own beliefs.

Ray duped Sumner on this one by goading him. “Must disagree with Ray at all costs” came at cost of self-contradiction.

26. February 2015 at 19:14

@MF – nice explanation! Remember, I am a chess player, and love to set traps!

@David de los Ãngeles BuendÃa – another awesome post brother, too bad Sumner ignores you.

@Steven Kopits – nice graphics, but you do realize that “potential GDP” has been discredited as nothing more than chart reading? Even and especially one time convert Brad DeLong recently blogged on this (Long-Run Real GDP Forecasts: The Hopeless Task of Trying to Pierce the Veil of Time and Ignorance Weblogging: by Brad DeLong Posted on February 24, 2015)

27. February 2015 at 04:58

New phrase and acronym for Keynesians.

The Negative 75 basis point or more lower bound.

N75BP+LB

27. February 2015 at 10:15

Ray –

I’m not a huge fan of potential GDP, but here’s a post on it. In some sense, it can be a useful guidepost, but I don’t ascribe religious significance to it.

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/12/28/regaining-potential-gdp

By the way, I have recently become more concerned that Scott may be right about labor shortages becoming a constraint on growth. On the other hand, that should be good for wages.

27. February 2015 at 10:20

Derivs –

You should probably visit my site every so often:

http://www.prienga.com/blog/

Below is the link to the forecast making the running right now. PIRA, EA, and the rest are slowly catching up as the data comes in, but this is the template right now, and I consider it directionally correct barring incoming data which would change my mind:

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2015/1/20/supply-minus-demand-explained

By the way, I’m making a tour through Houston next week, doing the Macro Oil Update. I have some slots left, for those interested.

28. February 2015 at 19:01

Steven, You said:

“Now, after Q2 2011, US and Euro Zone GDPs start to diverge from each other. The only material change in policy during this period is the 50 bp interest rate rise the Euro discount rate, which was quickly reversed.

Agree so far?”

Not at all. You keep judging monetary policy stances by the level of interest rates. You can’t do that. I’ll have a new post at Econlog in a day or so explaining why.

Also, Europe was hit by a demand shock, not a supply shock.