The debate our Fed ought to be having

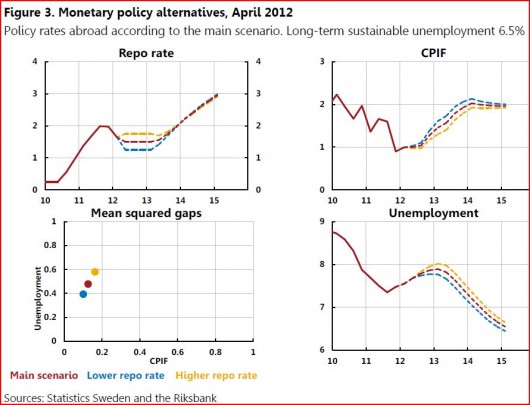

Stefan Elfwing sent me the minutes of the latest Riksbank meeting, and as usual Lars Svensson completely outclasses the competition. Here he discusses the forecast for the economy contingent on various paths of the policy interest rate (the repo rate.)

Svensson then makes the eminently logical suggestion that the Riksbank ought to choose the target path that best meets the mandate they’ve been given (which is 2% inflation and high employment–interpreted as the natural rate of unemployment equalling 6.5%) Svensson points out that the actual decision (keeping rates at 1.5%) produces an inferior outcome to the alternative lower interest rate path.

He prefaced his analysis by pointing to the basic “principle” of monetary policy. First predict the path of the economy under alternative policy scenarios, and then choose the path that best fulfills your mandate. It would be an understatement to suggest that other members were annoyed at Svensson pointing out the obvious:

Mr Jansson then commented on Mr Svensson’s contribution to the discussion regarding issues of principle. Mr Jansson said that he did not really understand the point of taking up these issues at the monetary policy meeting. These are questions that can be discussed at length, but there is not enough time available at a meeting of this nature. Mr Jansson said that Mr Svensson makes it sound as though the Executive Board has never discussed these issues before, which he considers to be totally misleading. These questions have often come up for lively discussion in recent years, and several of them have also led to concrete projects in the departments’ business plans. It is important that those outside the Riksbank are not given the impression that the Riksbank never talks about these issues.

Just imagine if the Fed presented not just its forecast for the economy, but also an alternative forecast for inflation and unemployment, conditional on a different amount of QE or a longer promise to hold rates at zero. “Yes, we could have done that, but chose not to.” I give the Riksbank a lot of credit for clearly explaining the alternatives to the path actually chosen.

Mr. Jansson also seemed perturbed that Svensson pointed out that the Riksbank had been significantly undershooting their inflation target, ever since the policy was adopted in the 1990s:

Mr Jansson considered that the new calculations presented by Mr Svensson rely on a number of assumptions that are rather difficult to digest. Firstly, it is assumed that the Riksbank for some reason should want to deliberately and systematically aim to attain a different inflation rate than the one it has chosen to introduce as a target. Disregarding the fact that this would appear to lack logic, it is something that Mr Jansson does not recognise at all from his almost 15 years of working at the Riksbank.

My goodness! What would make people believe that the Riksbank is intentionally undershooting their inflation target? Perhaps the fact that their own forecasts suggest that, given current policy settings, they are likely to miss their target. Of course the same is true of the Fed. Pity we don’t have someone like Svensson at the Fed; someone to shine a bright light on that policy failure.

Tags:

25. May 2012 at 08:39

Scott, I know you love Lars E. O. – and so do I to some extent. However, I am very frustrated that he like the rest of the New Keynesian bunch is so focused on interest rates. Interest rates in my view play only a minor role in the monetary transmission mechanism.

25. May 2012 at 08:44

Under the cover of discussing “Fed Communications” Kocherlakota does not resist pushing his “it´s structural” view once again:

To summarize: Labor market outcomes do remain notably worse than prior to the recession. The good news is that the unemployment rate has been declining since the end of the recession. But there is also countervailing evidence: The labor force participation rate has been falling steadily, and the employment/population ratio remains near its low point. The Beveridge curve shows considerable deterioration in labor market matching efficiency.

How persistent will these changes in U.S. labor markets prove to be? Economists hold at least two views on this question. The first is guided by the patterns in post-World War II data for the United States. These patterns suggest that the current deterioration in U.S. labor market performance is indeed reversible under appropriate policy.

The second view is less sanguine. It says that the post-World War II data do not contain an economic crisis of the kind or magnitude that hit the United States in 2008. Such a crisis could well have a different kind of impact on labor markets than the earlier postwar recessions.

And uses Sweden 20 years ago as confirming his views!

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/05/25/fed-official-says-the-problem-is-structural-there%C2%B4s-not-much-monetary-policy-can-do-to-help-revive-the-economy/

25. May 2012 at 08:48

As an entrepreneur who has a lot of friends who are also entrepreneurs, I find central bankers very frustrating.

When you’re running a startup, it’s really hard to determine what your intermediate goals should be. Sure, you want to build a company that has massive profits and happy employees in 5 years (or gets acquired by such a company), but there are a dozens of plausible intermediate goals that might achieve that end. And there’s no measuring stick to shows how good your aim currently is.

Moreover, you have dozens of tiny little levers you can pull to change your aiming point. But most of them have no effect and a few have massive effects. You just don’t know which ones have an effect or what their effect is.

Central bankers sit there with pretty clear goals and a few massive levers with pretty well understood effects.

And it’s the central bankers who are complaining that their job is hard?

25. May 2012 at 08:53

Lars, No one’s perfect, not even people named Lars. 🙂

Marcus, It’s sad to see central bankers focusing on output gaps.

Kevin, Good point. Their job is actually quite easy.

25. May 2012 at 10:42

I’m with Lars on this one. The focus on interest rates only obfuscates, but I can see communicating in such terms as necessary when your audience is so rooted in that thought process. Personally, I’ve found monetary policy much easier to understand once I learned to think of the Fed as operating on only one lever (

inflationNGDP). Reserves, interest on reserves, Fed funds, repo rates and all the rest are needless complications. The funny/sad thing is I think these additions confuse the central bankers themselves, in effect giving them cover to fail at their jobs indefinitely.25. May 2012 at 10:46

“Good point. Their job is actually quite easy.”

So easy that it could be automated?

http://www.moneyweek.com/news-and-charts/economics/uk/eocnomic-growth-market-monetarism-ngdp-20200

As I’ve been saying, the main problem with market monetarism is that it works too well. Central bankers respond to incentives like anyone else – they will fight the policy debate in a way that helps them keep their jobs.

25. May 2012 at 10:55

I have heard other commentators– economics professors even– insist that the Fed’s target of 2% inflation is really a ceiling. The Fed certainly acts that way. (And yes, this is related to the inherent connotation of “inflation==bad” that people have.)

25. May 2012 at 11:07

John –

Well those commentators and professors are exactly right. The 2% target is a ceiling. It shouldn’t be, but that’s the way the Fed has been treating it.

25. May 2012 at 12:35

Saturos,

“And this is where we get to the ‘market’ part of market monetarism (MMT for short).”

Oh dear.

25. May 2012 at 12:37

Cthorm, You said;

“I’m with Lars on this one.” So am I. I like both of their views on monetary policy. 🙂

Saturos, Yes, that’s undoubtedly true.

John, Unfortunately you are right. Except they only do this during recessions. They should treat it as a ceiling during booms and a floor during recessions.

25. May 2012 at 12:52

maybe Evans will carry the torch. we can only hope.

25. May 2012 at 13:31

The problem is that most of the people I’m talking about don’t just mean “it’s a ceiling” in the sense of describing what the Fed actually does, they actually mean it in the sense of what the Fed “should” do.

I think that it’s not quite the case that they “only do this during recessions.” I think that they always treat it as a ceiling, simply that in recessions that means doing nothing, whereas in booms it requires action.

25. May 2012 at 13:44

John –

“simply that in recessions that means doing nothing, whereas in booms it requires action.”

That may very well be true of the current Fed. We don’t know for sure, because there hasn’t been a boom since Bernanke took over. Greenspan was different: he allowed inflation to exceed his target (which was implicit to begin with) because he preferred his own judgement over policy rules.

Scott – Zing!

Regarding Evans, I was surprised to find out that he was a PhD student of Bennett McCallum. That really does a lot to explain why he favors NGDP targeting.

25. May 2012 at 14:31

Cthorm –

“Personally, I’ve found monetary policy much easier to understand once I learned to think of the Fed as operating on only one lever (inflationNGDP). Reserves, interest on reserves, Fed funds, repo rates and all the rest are needless complications.”

I definitely agree with this. The Fed can hit a target NGDP under any given set of those variables. Banks suddenly double their reserves? Then the Fed can double the monetary base to offset it. A new fad sets in where people refuse to use credit and strive to hold 6 months income in cash? Then the Fed increases the monetary base to offset it. These trends reverse? Then the Fed shrinks the monetary base to offset it. How does the Fed decide how much or how little to vary the monetary base? By targeting NGDP futures.

Once you look at it that way, then you realize our policy for all those other things should not be based on stimulating demand. Then the legal reserve ratio can be determined by the need to prevent bank failures that could cost the government, not whether we feel stimulus is needed. If anything, the government should want higher bank reserves so the Fed can make more profit for the Treasury.

The same goes for policies on consumer credit or anything else. No one would be able to argue that we need to encourage people to go into debt to keep the economy humming. If anything, the government should be discouraging consumer credit.

Assume the Fed will offset everything else the government does. The Sumner Critique on steroids!

25. May 2012 at 15:34

Damn, Scott is on to us!! Lars, I agree that short term interest rates are not the only thing that matter but given the experience with negative interest rates it is the main channel through which the riksbank signals their monetary policy stance to the market. So now the damn idiots told me to basically lengthen the term of my deposit and postpone my plans to buy an apartment, not because they increased the interest rate (they left it on hold) but because they signaled to me that they are less likely to stabilize demand. This is very significant because the market has been wondering for a while whether the Riksbank will repeat 08 policy if euroland goes under and the banks are not at immediate risk and now we got our answer (but luckily the Riksbank has been sending more positive signals lately).

So even though the interest rate per se is not that important, the stance that the CB conveys through it is.

26. May 2012 at 00:14

“Pity we don’t have someone like Svensson at the Fed; someone to shine a bright light on that policy failure.”

If you ask the folks on the FOMC, they will tell you it’s not a policy failure, but the best feature. They are economic sadists, get a rise out of undershooting.

All that hawk talk is killing us.

26. May 2012 at 04:04

“You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink”

Keynes thought there was no differenct between money & liquid assets. And all those on the FED’s technical staff are Keyneisans.

“Securities purchased (and sold) by the Fed, for example, could be absorbing assets that were held by the non-bank private sector or by the banking system itself.”

But the Fed’s research staff missed the corollary – IOeR’s “could be absorbing assets that were held by the non-bank private sector or by the banking system itself.”

http://www.chicagofed.org/digital_assets/others/events/2012/day_ahead/ennis_wolman.pdf

————————————————-

IOeR’s induce dis-intermediation where the financial intermediaries (non-banks), shrink in size — but the size of the commercial banking system stays the same). The Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond didn’t understand the implications of their comments.

————————————————-

IOeRs alter the construction of a normal yield curve, they INVERT the short-end segment of the YIELD CURVE – known as the money market.

The 5 1/2 percent increase in REG Q ceilings on December 6, 1965 (applicable only to the commercial banking system), is analogous to the .25% remuneration rate on excess reserves today (i.e., the remuneration rate @ .25% is higher than the daily Treasury yield curve almost 2 years out – .27% on 4/18/12).

In 1966, it was the lack of mortgage funds, rather than their cost (like ZIRP today), that spawned the credit crisis & collapsed the housing industry. I.e., it was dis-intermediation (an outflow of funds from the non-banks).

Just as in 1966, during the Great Recession, the Shadow Banking System has experienced dis-intermediation (where the non-banks shrink in size, but the size of the commercial banking system stays the same)

“Securities purchased (and sold) by the Fed, for example, could be absorbing assets that were held by the non-bank private sector or by the banking system itself.”

But the Fed’s research staff missed the corollary – IOeR’s “could be absorbing assets that were held by the non-bank private sector or by the banking system itself.”

SEE: http://www.chicagofed.org/digital_assets/others/events/2012/day_ahead/ennis_wolman.pdf

The fifth (in a series of rate increases), promulgated by the Board and the FDIC beginning in January 1957, was unique in that it was the first increase that permitted the commercial banks to pay higher rates on savings, than savings & loans & the mutual savings banks could competitively meet (like the CB’s IOeRs now compete with other financial assets [held by the non-banks], on the short-end of the yield curve).

Bankers, confronted with a remuneration rate that is higher (vis a’ vis), other competitive financial instruments, will hold a higher level of un-used excess reserves (i.e., will both 1. absorb existing bank deposits within the CB system, as well as 2. attract monetary savings from the Shadow Banks).

SEE: The inverted Eurepo curve spells trouble

http://soberlook.com/2012/05/inverted-eurepo-curve-spells-trouble.html

So IOeRs are not just a credit control device (offsetting the expansion of the FED’s liquidity funding facilities on the asset side of its balance sheet). But in the process ,they induce dis-intermediation (an economist’s word for going broke/bankrupt), in the Shadow Banks.

The effect of allowing IOeRs to “compete” with the returns generated from the financial assets held by the Shadow Banks, has been, and will be, to shrink the size of the Shadow Banks (as deregulation has in the last 50 years – with the exception of the GSEs).

However, disintermediation for the CBs can only exist in a situation in which there is both a massive loss of faith in the credit of the banks and an inability on the part of the Federal Reserve to prevent bank credit contraction, as a consequence of its depositor’s withdrawals.

The last period of disintermediation for the CBs occurred during the Great Depression, which had its most force in March 1933. Ever since 1933, the Federal Reserve has had the capacity to take unified action, through its “open market power”, to prevent any outflow of currency from the banking system.

Whereas disintermediation for the Shadow Banks (e.g., MMMFs), is predicated on their loan inventory (and thus can be induced by the rates paid by the commercial banks); i.e., the CBs earning assets, or IOeRs.

27. May 2012 at 06:34

dwb, Yes, he’d be the most likely.

John Thacker, That’s right.

Cthorm, Good point.

Orionorbit, Exactly.

Bonnie, Some of them, but not all. Some are capable of being convinced, in my view.

27. May 2012 at 23:19

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard continues to keep the ECB firmly in his sights, but the ECB seems to be even more locked into incompetence than the Fed.

28. May 2012 at 12:19

Lorenzo, Thanks. He’s always great.