The Bank of England’s inflation report

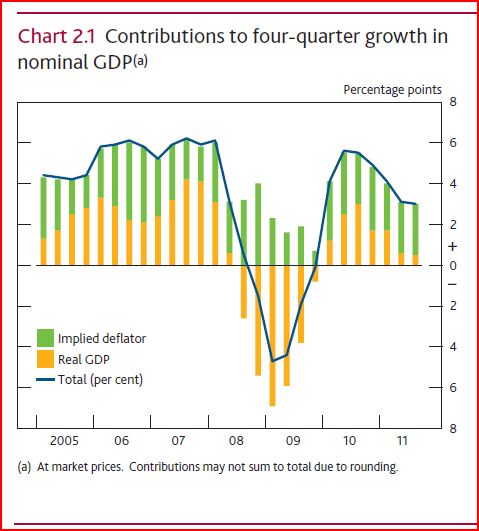

Commenter 123 sent me the February BOE inflation report, with this very interesting graph:

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

I suspect the NGDP instability contributed to fluctuations in RGDP growth, but it also looks like Britain has serious supply-side problems. Remember that the BOE inflation target is 2%.

I have a question for my Keynesian readers. Again and again the report refers to changes in real output as changes in “demand.” I’m pretty sure that’s Keynesian terminology, but it makes absolutely no sense to me. Here’s an example:

The pace of four-quarter global demand growth slowed in 2011. But, within that, there was some divergence in growth rates across different regions. And business surveys suggest that activity may have picked up a little in some countries at the beginning of this year (Chart 2.8). Against the backdrop of subdued global demand growth, world trade rose only modestly in the year to November 2011.

Chart 2.8 shows output trends, not AD. They also refer to real domestic final sales (C+I+G) as “domestic demand.” I find this terminology bizarre, but maybe I’m missing something. For instance, suppose the AD curve was stable, and the AS curve shifted to the right, producing real economic growth. The BOE would apparently call that real growth an increase in “demand” even though it was caused by an increase in supply. It seems to me that causes needless confusion, and is likely to lead one to overemphasize the importance of demand shocks in driving RGDP growth.

I prefer to call NGDP “demand.” In that case a rise in AS doesn’t have any impact on demand, but rather increases both supply and real GDP.

PS. There is a lot of confusion about the impact of supply-side problems on economic growth. All countries including Switzerland and Congo grow at the same rate in the long run. It’s all about levels. Efficient countries have a per capita GDP closer to the richest (non-oil) country than less efficient countries. Britain recently raised the size of its government as a share of GDP from 37% to 50%. Some of that was cyclical, but not all. This will slightly reduce Britain’s steady state GDP per capita relative to the richest country, but will not permanently reduce it’s growth rate. It may currently be in transition, say from 70% of Singapore’s GDP/person to 63%. If so, it will grow a total of 10% less than normal during that period of transition, which might last a decade. Obviously I just pulled these numbers out of a hat, to illustrate the proper way to think about supply-side issues.

PPS. The Economist estimates that in 2012 Britain’s GDP/person will be 69.5% of Singapore’s. The US will be at 94.5%, not bad for a country with brain-dead policymakers.

Tags:

25. February 2012 at 08:54

Yes, higher G/Y can be bad for the economy´s “health”:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/01/31/the-austerity-debate/

25. February 2012 at 09:35

Marcus, Good post–interesting that government grew least in the English speaking countries.

25. February 2012 at 09:37

The use of RGDP to mean “demand” also means that the 1974-1975 period was a period of falling demand in the UK, even though expenditure rose dramatically.

I suspect it’s partly a legacy of the “Y = etc.” definition of national income and partly a consequence of the distinction between the I = S curve from the L = M. If there’s no “P” in your definition of national income and you don’t like do deal with L = M, then the perpetually strong temptation in economics to ignore inflation and money becomes almost overwhelming.

One factor in the UK’s weak supply-side performance is presumably the weakness of our financial sector right now, which is not helped by the determination of successive governments to drive it into the ground with sector-specific taxation and regulation. When oil prices fell through the floor in the 1980s and caused a crisis in their economy, Nigerians didn’t put an “excess profits” tax on their oil companies. Yet the UK has done just that at a time when many major banks are running losses. And this is before Basel III hits the financial sector.

Perhaps the UK can learn a lesson in good governance from Nigeria.

25. February 2012 at 14:25

“For instance, suppose the AD curve was stable, and the AS curve shifted to the right, producing real economic growth. The BOE would apparently call that real growth an increase in “demand” even though it was caused by an increase in supply.”

If this was true, they’d be lazy undergrads. They would probably mean ‘quantity demanded’.

However, in the paragraph you cited, it doesn’t seem to be a problem; they do in fact seem to correctly mean “aggregate demand” in that selection.

25. February 2012 at 17:17

Scott,

My intuition tells me that the biggest supply side offenders in the EU are the UK, Greece and Portugal (in that order). But notice the UK has no debt crisis.

The nominal problems are real. And the real problems are nominal. Go figure.

25. February 2012 at 22:21

For instance, suppose the AD curve was stable, and the AS curve shifted to the right, producing real economic growth. The BOE would apparently call that real growth an increase in “demand” even though it was caused by an increase in supply.

I prefer to call NGDP “demand.” In that case a rise in AS doesn’t have any impact on demand, but rather increases both supply and real GDP.

This is interesting. Sumner said something I agree with! Take that CA!

25. February 2012 at 23:08

Glenn Stevens, the Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, was asked about nominal GDP targetting in Parlimentary testimony.

Didn’t seem much of a fan, though Australia does have specific issues with its swings in terms of trade/commodity prices.

Link Below, page 12.

http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/committees/commrep/e7dbd7b4-a20a-4de6-a315-f76b0e1fabd2/toc_pdf/Standing%20Committee%20on%20Economics_2012_02_24_844.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22committees/commrep/e7dbd7b4-a20a-4de6-a315-f76b0e1fabd2/0000%22

26. February 2012 at 02:53

[…] Take a Scott Sumner’s discussion of Bank of England’s inflation. You will see Scott is struggling with the BoE’s research […]

26. February 2012 at 07:12

W. Peden, I agree about weakness in the financial sector.

But I’m puzzled by various people trying to explain the BOE’s views on demand as simplistic 1960s Keynesianism. After all, they do discuss NGDP growth, and they clearly do understand inflation and supply shocks. So I wonder how they’d defend this language.

Benjamin, No they do not refer to AD. There and elsewhere they clearly mean RGDP. Look at chart 2.8. Also look at where they talk about “domestic demand” and refer to real C+I+G.

Mark, I’d say Greece is the worst.

Major Freeman. Finally!

Antipodes, That was very interesting. The RBA seems in good hands.

26. February 2012 at 08:57

Scott Sumner,

If the discussion of their policies by economists and politicians uses the naive Keynesian model, then I suspect that the BoE will try to use that model as much as possible and will at the very least be held accountable (or unaccountable) to it.

If everyone talked in terms of NGDP, then the BoE would use that language and through that language it would be able to justify better policies (like an NGDP target).

26. February 2012 at 14:05

W. Peden

UK banks were horribly over-leveraged and are horribly too big. They are like the US auto-industry, horribly feather-bedded. But worse than that, apologists for them like you seem to be, argue they need to be left alone to take risks safe in the knowledge that all their gains will be private and all their losses socialized (to borrow Martin Wolf’s classic description). This is not free market capitalism in action but state-backed corporatism.

Banks have a very high opinion of themselves and their social usefulness, it is up to the populace to be as constantly on it’s guard against these super-successful lobbyists as they need to be against government itself and all its state-backed academic supporters.

26. February 2012 at 14:50

James in London,

“UK banks were horribly over-leveraged and are horribly too big.”

Given the absence of anything resembling free market in British finance, I don’t see how such judgements can be made.

The tax on banks is only one part of the problem. Clearly, the banks are in want of market discipline. Even the old LOLR + a nice hefty penalty rate would have been preferable to the shambles of 2008.

It’s possible to believe BOTH that the bank tax + most accompanying regulations are a bad idea (because they involve going after one of the strongest parts of the UK economy) AND that the banks’ need more market discipline. Just as it’s possible to think that another notable sector-specific tax in UK history, Selective Employment Tax, was BOTH a lousy idea AND that British service industries generally needed more exposure to competition (e.g. that the interest rate cartel in banking should have been ended and the Post Office’s monopoly needed to be lifted, as it was in part in the 1980s).

There were people opposed to SET who weren’t apologists for the services industries. Equally, there are people opposed to the current government’s toxic mix of sector-specific taxation, politically-motivated regulation of dubious utility even in theory, AND a new industrial policy based on taxpayer underwriting of banks’ mistakes.

27. February 2012 at 08:30

I’m a little late to the part here, but that Domestic Demand point was pretty silly. If you’re going to use Keynesian terminology, C+I+G is a ridiculous definition for ‘domestic demand’. When I used to do this sort of farcical analysis on an industry level, we at least had the decency to define Domestic Demand as C+I-M.

27. February 2012 at 08:41

“When I used to do this sort of farcical analysis on an industry level, we at least had the decency to define Domestic Demand as C+I-M.”

No wonder you call it farcical. Leaving aside any confusion between demands and quantities demanded…

If Y is domestic production, and X is foreign demand for domestic production, then Y-X = C+I+G-M would be domestic demand for domestic production.

Obviously, M is domestic demand for foreign production, so Y-X+M = C+I+G is domestic demand.

27. February 2012 at 09:47

W.Peden

I don’t think I saw any comment on state corporatism or regulators getting captured by those they (fail to) regulate.

I agree it’s a most dispiriting mess, but I don’t know what is more dispiriting: corporatist bankers talking BS about their essential “social utility” in providing credit to the real economy, whatever that means; or regulators “interfering” in banks and trying to make them sound enough to not call on the taxpayer guarantee again. Probably the former, but it’s a close call.

That is why breaking up the banks and thus being able to introduce a real free market, with the possibility of individual failure, is best policy.

27. February 2012 at 10:30

“All countries including Switzerland and Congo grow at the same rate in the long run.”

Wait a minute…WHAT?!?! I am sorry, but I am confused. You are telling me that Singapore and North Korea will grow at the same rate in the long run? Their policies do not matter at all. I must not be getting something.

27. February 2012 at 18:50

W. Peden, Yes, but I’m making a slightly different point. I’m not saying they must talk about NGDP. I’m fine with talking about RGDP. It’s just that if they do so, why not call it “output,” which is what it is, not “demand” which is not what it is.

You can’t say the economy grew in the third quarter because of a rise in “demand”, if you define demand as output. Because then you’d be saying “output increased in the third quarter because of an increase in output.”

Cthorm, They also have “private demand” as I recall, which excludes G.

Liberal Roman. In the long run countries tend to grow at a rate determined by technological progress. In the short run countries can moving closer to or farther from the technological frontier. So Singapore is currently at the frontier, and will probably grow at the rate the frontier expands for the foreseeable future. If Korea reforms its economy they will have a period of faster catchup growth. When they get done catching up they’ll grow at the same rate as Singapore. If they don’t, they may stay at 10% of Singapore’s per capital income and grow at the same rate.

27. February 2012 at 18:52

Hmmm, reading this brings two thoughts to my mind:

1. Glad I ain’t living in Britain. It was by far my favorite tourist destination as yet another fat American, and it would be my favorite place to live if I had a ton of money, but things sound tough for the commonfolk. You guys got the worst of both worlds: corporatist policies from the right and big, inefficient government from the left. I know everybody hates Margaret Thatcher over there, but it looks like the government is starting to run out of other people’s money. Only very homogeneous countries with low corruption and high values of social trust can make true socialism work out, and even the Nordic countries like Sweden and Denmark have steadily liberalized over the years.

2. One of my favorite parts of NGDP targeting is that it brings clarity to how so much economic rhetoric is BS. If the BOE successfully kept NGDP targeting, then Barclays or RBS or whoever would not be needed to lend to the economy. Assuming that investors don’t like keeping Pounds on the table, they will lend under the assurance that NGDP will be kept at a certain growth rate. For the pure sake of everyone having a job who is not a ZMP worker, NGDP targeting and labour policy liberalization ensures that everyone would have a job paying a bit less than what they produce.

28. February 2012 at 07:22

Matt, Good point.