Who are the famous bubble deniers?

More and more I think that the entire bubble/anti-EMH approach to economics is founded on nothing more than superstition. Superstitions are caused by cognitive illusions; we think we notice more patterns than are actually there. You dream your son got in a traffic accident, and the next day it happens. You forget the other 10,000 dreams that didn’t predict the future.

In economics people notice bubbles bursting, but fail to pay much attention to bubbles not bursting. But I admit I might be wrong, so I’ll give my opponents one more chance. If it’s not really a cognitive illusion, then bubble deniers who are right ought to be just as famous as bubble predictors who are right. Indeed as we will see they should be even more famous.

People who actually understand finance know that if the term “bubble” is to mean anything useful, it must contain an implied prediction of the future course of asset prices. Not a precise prediction (everyone knows that would be impossible) but at least a better than a 50/50 prediction. If someone said in 2005 that housing prices were a bubble, but still was unable to offer more than a 50/50 odds on whether real housing prices would rise or fall over the next 5 or 10 or 20 years, then what would their assertion actually mean? Asset prices are very volatile; we know that at some point all markets will go down. When I read predictions from people like Paul Krugman, I infer that there is an implied prediction that real prices will fall over some reasonable period of time—say 5 years.

And of course Krugman was right in predicting that real US housing prices would fall in the 5 years after 2005, as was Dean Baker, Nouriel Roubini, and some others who became well known and lauded for their predictions.

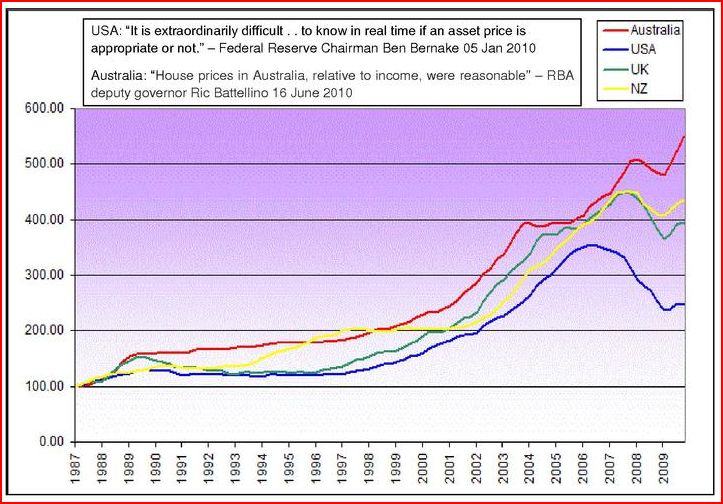

At the same time we also know that bubble-like patterns don’t always yield reliable predictions of future trends. The Australian housing market looked just as bubbly as the US market in 2005, but since then has soared much higher. Some day it will fall, but the 2005 prices no longer look excessive.

If people like Robert Shiller (another person who became famous from bubble predictions) are right about asset prices being too volatile, then it should be true that US-type cases are more common than the Australian case. I don’t think that’s true— in most developed countries real housing prices have risen since 2005, despite real upswings before 2005. But let’s say I’m wrong and Shiller’s right. Then the easy prediction to make is that prices will fall after a big upswing. The much harder prediction is that prices will keep rising, even from inflated levels. Those cases would be much rarer, and those who correctly call them when they occur (as in the Australian housing case) should be lauded as great heros of the investment world.

So who are they?

If they don’t exist, I have a theory why. Most people are convinced bubbles exist, regardless of the data. Hence if the prediction doesn’t pan out, then the market was in some sense “wrong.” Traders haven’t yet woken up to the stupidity of their behavior. When they do, prices will crash and the bubble proponents will be proven right in the long run. So most people would implicitly think; “Why praise someone for being right for the wrong reason?” Of course this makes bubble theory into a near tautology, irrefutable in volatile asset markets that will almost always eventually show price decreases.

Perhaps I am wrong and there are lots of famous bubble deniers out there. But if not, that would in my mind be the last nail in the anti-EMH coffin, pretty much confirming that people are seeing what they expect to see, indeed given the satisfaction we get from seeing the high and mighty brought low, perhaps what they want to see.

One final point; I also have noticed that lots of people are given credit for bubble predictions that were wrong. John Kenneth Galbraith saying stocks were a bubble in January 1987. Robert Shiller saying stocks were a bubble in 1996. Dean Baker saying US housing was a bubble in 2002. The Economist magazine touting its successful housing bubble predictions of 2003 in an ad, despite the predictions being incorrect for most of the countries listed. That’s how strongly we want to believe in bubble predictions—we even assume that people who were wrong, were actually right.

PS. For those interested in global housing prices, The Economist has a great interactive graph. It helps to show the pattern from say 2000:1 to 2005:1, and then from 2005:1 to the present. In the earlier period almost all countries showed gains in housing prices, even in real terms. The two notable exceptions were Germany and Japan, where prices fell sharply. If I was to use a Shiller-style model that predicts asset prices will self-correct after excessive swings, I would have predicted most housing markets to slump after 2005:1, but Germany and Japan to rise. Instead almost the opposite happened. Germany and Japan continued to do very poorly, while almost all other markets rose in nominal terms, and most rose even in real terms.

The two nominal decliners (in addition to Germany and Japan) were the US and Ireland—which is why people assume they had had a bubble. But why didn’t all the other bubbles collapse? Perhaps because asset prices are not as easily forecasted as most people naively assume.

BTW, if you can’t get a 2000:1 starting date, then white out all the country boxes and start over. That worked for me.