OSAKA, Japan “” Like many members of Japan’s middle class, Masato Y. enjoyed a level of affluence two decades ago that was the envy of the world. Masato, a small-business owner, bought a $500,000 condominium, vacationed in Hawaii and drove a late-model Mercedes.

But his living standards slowly crumbled along with Japan’s overall economy. First, he was forced to reduce trips abroad and then eliminate them. Then he traded the Mercedes for a cheaper domestic model. Last year, he sold his condo “” for a third of what he paid for it, and for less than what he still owed on the mortgage he took out 17 years ago.

“Japan used to be so flashy and upbeat, but now everyone must live in a dark and subdued way,” said Masato, 49, who asked that his full name not be used because he still cannot repay the $110,000 that he owes on the mortgage.

Few nations in recent history have seen such a striking reversal of economic fortune as Japan.

. . .

The downsizing of Japan’s ambitions can be seen on the streets of Tokyo, where concrete “microhouses” have become popular among younger Japanese who cannot afford even the famously cramped housing of their parents, or lack the job security to take out a traditional multidecade loan.

These matchbox-size homes stand on plots of land barely large enough to park a sport utility vehicle, yet have three stories of closet-size bedrooms, suitcase-size closets and a tiny kitchen that properly belongs on a submarine.

“This is how to own a house even when you are uneasy about the future,” said Kimiyo Kondo, general manager at Zaus, a Tokyo-based company that builds microhouses.

. . .

The decline has been painful for the Japanese, with companies and individuals like Masatohaving lost the equivalent of trillions of dollars in the stock market, which is now just a quarter of its value in 1989, and in real estate, where the average price of a home is the same as it was in 1983. And the future looks even bleaker, as Japan faces the world’s largest government debt “” around 200 percent of gross domestic product “” a shrinking population and rising rates of poverty and suicide.

But perhaps the most noticeable impact here has been Japan’s crisis of confidence. Just two decades ago, this was a vibrant nation filled with energy and ambition, proud to the point of arrogance and eager to create a new economic order in Asia based on the yen. Today, those high-flying ambitions have been shelved, replaced by weariness and fear of the future, and an almost stifling air of resignation. Japan seems to have pulled into a shell, content to accept its slow fade from the global stage.

. . .

The classic explanation of the evils of deflation is that it makes individuals and businesses less willing to use money, because the rational way to act when prices are falling is to hold onto cash, which gains in value. But in Japan, nearly a generation of deflation has had a much deeper effect, subconsciously coloring how the Japanese view the world. It has bred a deep pessimism about the future and a fear of taking risks that make people instinctively reluctant to spend or invest, driving down demand “” and prices “” even further.

. . .

A Deflated City

While the effects are felt across Japan’s economy, they are more apparent in regions like Osaka, the third-largest city, than in relatively prosperous Tokyo. In this proudly commercial city, merchants have gone to extremes to coax shell-shocked shoppers into spending again. But this often takes the shape of price wars that end up only feeding Japan’s deflationary spiral.

There are vending machines that sell canned drinks for 10 yen, or 12 cents; restaurants with 50-yen beer; apartments with the first month’s rent of just 100 yen, about $1.22. Even marriage ceremonies are on sale, with discount wedding halls offering weddings for $600 “” less than a tenth of what ceremonies typically cost here just a decade ago.

. . .

“It’s like Japanese have even lost the desire to look good,” said Akiko Oka, 63, who works part time in a small apparel shop, a job she has held since her own clothing store went bankrupt in 2002.

This loss of vigor is sometimes felt in unusual places. Kitashinchi is Osaka’s premier entertainment district, a three-centuries-old playground where the night is filled with neon signs and hostesses in tight dresses, where just taking a seat at a top club can cost $500.

But in the past 15 years, the number of fashionable clubs and lounges has shrunk to 480 from 1,200, replaced by discount bars and chain restaurants. Bartenders say the clientele these days is too cost-conscious to show the studied disregard for money that was long considered the height of refinement.

“A special culture might be vanishing,” said Takao Oda, who mixes perfectly crafted cocktails behind the glittering gold countertop at his Bar Oda.

After years of complacency, Japan appears to be waking up to its problems, as seen last year when disgruntled voters ended the virtual postwar monopoly on power of the Liberal Democratic Party. However, for many Japanese, it may be too late. Japan has already created an entire generation of young people who say they have given up on believing that they can ever enjoy the job stability or rising living standards that were once considered a birthright here.

Yukari Higaki, 24, said the only economic conditions she had ever known were ones in which prices and salaries seemed to be in permanent decline. She saves as much money as she can by buying her clothes at discount stores, making her own lunches and forgoing travel abroad. She said that while her generation still lived comfortably, she and her peers were always in a defensive crouch, ready for the worst.

“We are the survival generation,” said Ms. Higaki, who works part time at a furniture store.

Hisakazu Matsuda, president of Japan Consumer Marketing Research Institute, who has written several books on Japanese consumers, has a different name for Japanese in their 20s; he calls them the consumption-haters. He estimates that by the time this generation hits their 60s, their habits of frugality will have cost the Japanese economy $420 billion in lost consumption.

“There is no other generation like this in the world,” Mr. Matsuda said. “These guys think it’s stupid to spend.”

Deflation has also affected businesspeople by forcing them to invent new ways to survive in an economy where prices and profits only go down, not up.

Yoshinori Kaiami was a real estate agent in Osaka, where, like the rest of Japan, land prices have been falling for most of the past 19 years. Mr. Kaiami said business was tough. There were few buyers in a market that was virtually guaranteed to produce losses, and few sellers, because most homeowners were saddled with loans that were worth more than their homes.

Some years ago, he came up with an idea to break the gridlock. He created a company that guides homeowners through an elaborate legal subterfuge in which they erase the original loan by declaring personal bankruptcy, but continue to live in their home by “selling” it to a relative, who takes out a smaller loan to pay its greatly reduced price.

“If we only had inflation again, this sort of business would not be necessary,” said Mr. Kaiami, referring to the rising prices that are the opposite of deflation. “I feel like I’ve been waiting for 20 years for inflation to come back.”

One of his customers was Masato, the small-business owner, who sold his four-bedroom condo to a relative for about $185,000, 15 years after buying it for a bit more than $500,000. He said he was still deliberating about whether to expunge the $110,000 he still owed his bank by declaring personal bankruptcy.

Economists said one reason deflation became self-perpetuating was that it pushed companies and people like Masato to survive by cutting costs and selling what they already owned, instead of buying new goods or investing.

“Deflation destroys the risk-taking that capitalist economies need in order to grow,” said Shumpei Takemori, an economist at Keio University in Tokyo. “Creative destruction is replaced with what is just destructive destruction.”

Before commenters like Greg jump all over me, re-read the intro. I never claimed the adoption of the 0% NGDP growth policy had anything to do with the dreary story described by the NYT. And I’m not sure it does. There’s nothing wrong with touting a country as a smashing success in one area, even if you disagree with its policies elsewhere. I’m always praising Singapore’s fiscal policy, yet I detest many policies of the Singapore government. It could well be that the bad performance of Japan’s economy was caused by supply-side factors unrelated to monetary policy. Some bloggers even claim the Japanese haven’t done all that bad.

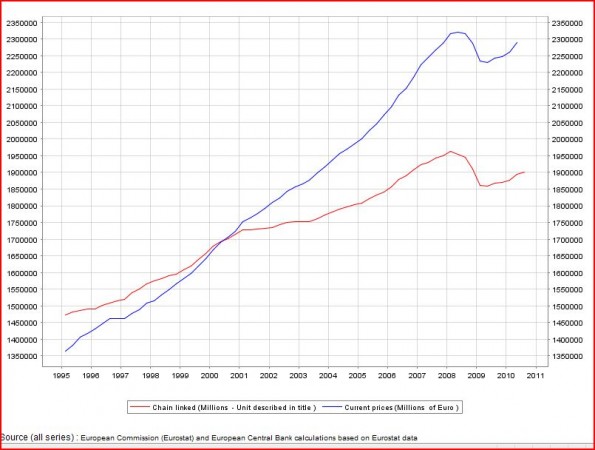

And yet . . . let’s be honest. This is a big problem for the 0% NGDP growth fans. Japan’s slide into stagnation co-incided almost exactly with the (de facto) adoption of a stable NGDP rule. And it’s the only country I know that has adopted this policy. And before the policy was adopted most mainstream economists thought deflation was a really bad idea. Put that all together and I think “zero percenters” have got a massive PR problem.

Yes, the US grew rapidly in the late 1800s under deflation, but we had strong NGDP growth. Japan doesn’t. Are there any examples of countries doing well with stable NGDP? I don’t know of any. Unless someone can find plausible counterexamples, that makes Hayek’s argument a really hard sell.

Why is this important? Because Hayek’s argument underlies the Austrian view that monetary policy was too “inflationary” during the 1920s, despite no rise in the price level. He argued NGDP should have been kept stable, so prices could fall with productivity gains. This argument also underlies some of the critique of Fed policy in the 2000s, as price inflation wasn’t all that high. In fairness, some point to the rapid NGDP growth after 2003 as a problem, and I partly agree. So the critique of the Fed in this case seems stronger from a NGDP targeting perspective. But still nowhere near as strong as the critique of their policy of allowing NGDP growth to plummet in the midst of a financial crisis.