A note on life expectancy and development

Dani Rodrik has an interesting post discussing how some North African countries have done surprising well in terms of the human development index, despite seeing much slower rates of GDP growth than the more famous East Asian models:

Which are the countries that have improved their human development indicators the most since 1970 relative to their peers? You’d be surprised, as I was, to find that the top 10 is dominated not by East Asian superstars, but by Moslem countries: Oman, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria. This year’s Human Development Report is full of neat analysis and results, including this one.

Leaving aside the oil exporting countries, the North African cases are particularly interesting. As Francisco Rodriguez and Emma Samman, two of the report’s authors, note, Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria have experienced remarkable gains in life expectancy and educational attainment, leaving many Asian superstars in the dust.

Rodriguez and Samman make the following claim:

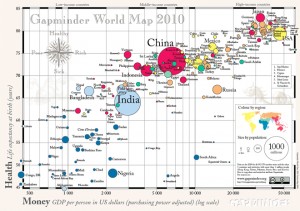

Consider the following comparison. In 1970, a baby born in Tunisia could expect to live 54 years; one born in China, 62 years. Today, life expectancy in Tunisia has risen to 74 years, a year longer than that of China. So while China’s per capita income grew almost three times as fast as Tunisia’s, Tunisia’s life expectancy grew twice as fast as China’s. Since it also significantly outperformed China on the education front, Tunisia gives China a run for its money in the overall development story (as captured by the HDI).

I don’t wish to challenge this finding, partly because I am not an expert in this area. Tunisia’s performance does look impressive, and we all know China’s health care and education systems have some gaping holes. Instead I’d merely like to suggest we need to be very careful when considering the impact of economic development on life expectancy. Life expectancy at birth is a sort of snapshot that reflects conditions over a very long period of time.

I believe that life expectancy at birth in China is now much higher than the official statistics show, as those data are measuring life expectancies for people born at various times over the past 100 years. And I hope to convince you that the average person born in China today will live longer than the average person born in Denmark today.

One factor that has held back China is the poor health of its rural population. Part of that reflects poor health care facilities and part reflects environmental risks. But I also think a large part reflects poor health when young. Chinese who are 50 years old were born during the Great Leap Forward, when between 20 and 40 million Chinese starved to death, and many more suffered malnutrition. This link has data from an interesting study of Dutch people born during the 1944-45 famine in Holland. It turns out those people had consistently worse health during their entire lives.

Admittedly, only a small share of the Chinese population was born during the GLF, but most older people were born during periods of political and economic turmoil. Indeed until the land reform of 1979 sharply boosted food output, much of the countryside was chronically malnourished. Old people dying today (which make up a large part of the data from which we estimate life expectancy at birth), lived most of their lives in a country as poor as India and Sub-Saharan Africa were during the same time period. That’s much poorer than Tunisia.

The following list is the CIA estimate of life expectancy in 2009, which is the most recent I could find. I excluded nations with fewer than 100,000 people.

1. Macao 84.36

2. Japan 82.12

3. Singapore 81.98

4. Hong Kong 81.86

5. Australia 81.63

5.b Shanghai in 2008 81.28

6. Canada 81.23

.

.

40. South Korea 78.72

46. Denmark 78.30

50. U.S. 78.11

72. Tunisia 75.78

105. China 73.47

What do you notice? I see East Asian countries scoring really high, and the highest western countries being places with lots of East Asian immigrants. I also see Korea and China lagging somewhat, with indications (from Shanghai) that the problem in China is in rural areas. The other laggard (Korea) is also a country that suffered extreme poverty and war during the 1950s. I believe that Shanghai was less affected by famines than the countryside, although it also has better health care, so it’s hard to know what explains the difference. But I find the Korean case especially interesting; it suggests that the long cloud of history affects life expectancy for quite some time, at least when conditions were extremely bad in previous decades.

This data also suggests that environmental factors may be overrated. Obviously air pollution is extremely bad in Hong Kong and Shanghai, yet both places have extremely high (and fast rising) life expectancy. Undoubtedly there are industrial areas of China where local health suffers due to chemical spills, etc, but I’d guess the nationwide life expectancy is more affected by other factors, such as childhood nutrition, smoking, and current health facilities and access.

I claimed that I would try to convince you that Chinese born today might live longer than Danes born today. That’s already true for Chinese living in places like Beijing, Shanghai and other wealthy coastal cities. My claim is that today even children in the Chinese countryside generally do not suffer from malnutrition (with very localized exceptions) and by the time they are old enough where medical facilities become very important in longevity (say in 50 or 60 years), even interior China will be at least as rich as Shanghai is today.

Why do Asian countries lead the world in life expectancy? Not because they spend a lot on health care, but rather some other factors (perhaps diet, culture, lifestyle, genetics, etc.) Whatever the reason, I’d expect the East Asian/Western gap to become even more noticeable over time, as the older generation of Chinese and Koreans dies off, and all of East Asia converges to Japanese life expectancies.

One reason I indicated that I didn’t wish to challenge the Rodriquez and Sammon finding is that they look at changes in life expectancy–and Tunisia’s has risen faster than China’s. Whether my argument is at all relevant to that claim is a surprisingly complex question that I’ll just hint at here. It depends on both the change in current health care, environmental, and nutrition conditions, as well as the extent to which chronic health problems developed in earlier decades can be ameliorated by those improvements. I’ll leave that to others. And of course they also look at many other indicators of development, such as education.