Supply-side success in Britain

In an earlier post I criticized a paper by Emmanuel Saez and Peter Diamond. Now Tyler Cowen links to an interview of Saez.

You see the highest increases in income concentration in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, following precisely what has been called the Reagan and Thatcher revolutions: deregulation, cuts in top tax rates, and policy changes that favored upper-income brackets. You don’t see nearly as much of an increase in income concentration in countries such as Japan, Germany, or France, which haven’t gone through such sharp, drastic policy changes.

That’s a respectable argument, if you ignore that fact that income data is completely meaningless. But I’m the only one who seems to believe that, so let’s assume I’m wrong. Let’s assume that when I sell my house for a gain of $500,000 (a gain that is purely inflation), that number will accurately describe my economic situation, or “class”, not my consumption level of $100,000.

It could be argued that the increase in income inequality was worth it, as it boosted economic growth. Here’s how Saez responds:

The standard story among economists is that if those in the top bracket earn more that’s because they are working more and contributing more to the economic pie. So in that scenario, reducing top tax rates and having higher incomes at the top would be a good thing. However, if that were the case, the growth in top incomes should not come at the expense of lower incomes and it should stimulate economic growth. The difficulty, however, is that if you look at the data you don’t see clear evidence that countries who cut their top tax rates and experienced a surge of top incomes did experience overall better economic growth.

An alarming fact in the United States concerns the patterns of economic growth of the top 1 percent versus the bottom 99 percent. We know that in the long run economic growth leaves all incomes growing. If you take as a century long picture, from 1913 to present, incomes for all have grown by a factor of four. But then when you look within that century of economic growth, the times at which the two groups were growing are strikingly different. From the end of the Great Depression to the 1970s, it’s a period of high economic growth, where actually the bottom 99 percent of incomes are growing fast while the top 1 percent incomes are growing slowly. It’s not a good period for income growth at the top of the distribution. It turns out that that’s the period when the top tax rates are very high and there are strong regulations in the economy. In contrast, if you look at the period from the late ’70s to the present, it’s the reverse. That’s a period when the bottom 99 percent incomes are actually growing very slowly and the top 1 percent incomes are growing very fast. That’s exactly the period where the top tax rates come down sharply. So, of course this doesn’t prove the rent-seeking scenario but it is more consistent with it than with the standard narrative.

This argument puzzled me. Why is Saez no longer comparing the US and UK to the other countries? Perhaps because the slowdown in growth in the other countries (after the 1970s) was much more dramatic than the slowdown in growth in the US. In fairness, the US is somewhat of a special case, as we came out of WWII in great shape. The fast growth in other countries between 1950 and 1980 was partly “catch-up growth,” and you’d expect a slowdown as per capita GDP levels approach US levels. Fair enough, nonetheless at a minimum it would be worth comparing the growth rate of Britain and the others.

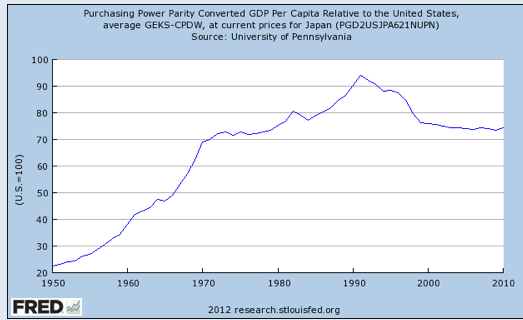

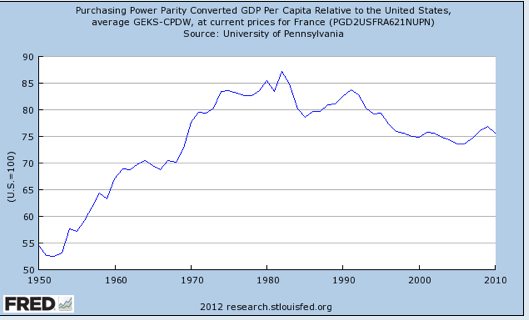

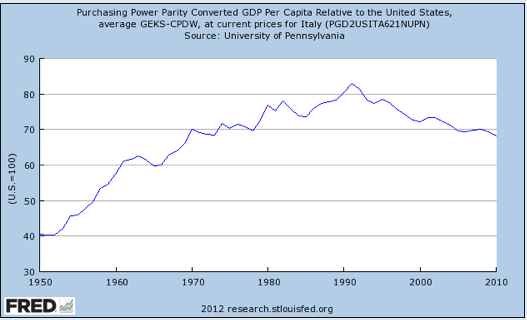

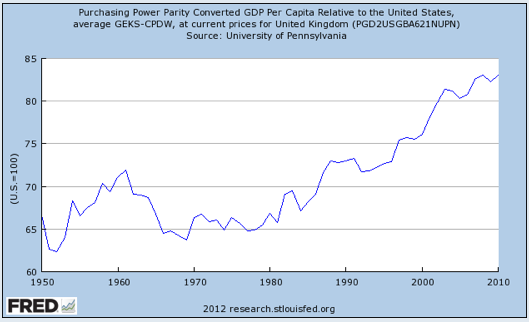

Fortunately the St Louis Fred has some nice graphs showing the ratio of each country’s per capita GDP (in PPP terms) to the US, from 1950 to 2010. Let’s see if Saez is right:

Japan hasn’t gained any ground since Reagan took office in 1981, and might even have slightly regressed.

France was gaining on the US before Reagan took office in 1981, and has since regressed. The St Louis Fed doesn’t have comprehensive data on Germany, and the data it does have looks inaccurate (and doesn’t really differ much from Japan.) So let’s use Italy instead:

Not all that different from Japan and France. Now let’s look at Britain, which did even more aggressive supply-side reforms than the US:

Whoa!! What happened to the UK after 1979! No wonder Saez stopped talking about the relative performance of the US and UK as soon as he shifted the discussion to changes in RGDP growth over time. The data actually suggests the supply-side reforms did cause a relative improvement in RGDP growth. Not an absolute improvement, but relative to the slowdown in RGDP growth that was occurring almost everywhere in the world.

PS. I do understand one can cut the data in all sorts of ways, and make all sorts of arguments for high MTRs that Saez did not make. I addressed the argument he did make, not hypothetical arguments he didn’t make.

BTW, I happen to favor progressive taxes on the rich, as long as they are consumption taxes, not income taxes. I’d also like to see policy reforms reducing rents earned by the rich. So this post is not bashing egalitarianism. I’m a utilitarian. I’m bashing income taxes, which are a moral and practical abomination. The only ethically acceptable income tax rate is zero.

PPS. I hope people realize I was using a colorful writing style. I don’t think Saez was being intentionally disingenuous—people tend to gravitate toward data that supports their argument.

Tags:

2. March 2013 at 11:41

To what extent are taxes on (wage) income actually different from a consumption tax?

2. March 2013 at 12:35

Would a response from Saez be that most of the additional gdp per capita is gobbled up by those on higher incomes in the UK and US. You need to look at median income/or possibly spending rather than average (gdp ppp per capita) on that sort of account.

2. March 2013 at 12:35

Prof. Sumner,

If utilitarianism is the correct moral framework for public policy (and human action in general), why should wealth redistribution be primarily focused on American rich to American poor?

Shouldn’t utilitarians be arguing for massive transfers out of the wealthy OECD nations and into the absolutely impoverished areas of the world?

2. March 2013 at 12:41

Would a response from Saez be that most of the additional gdp per capita is gobbled up by those on higher incomes in the UK and US? You need to look at median income/or possibly spending rather than average (gdp ppp per capita) on that sort of account.

2. March 2013 at 12:46

His point though isn’t about growth rates- per capita or no- but more polarized distribution.

Whether or not Brtiain has a higher growth rate since 1980-whether relative to the US or not- if we had Germany here we wouldn’t see the same result- is not what he’s getting at.

It’s about the distribution of income-as you think that’s a meaningless term and he doesn’t that’s something else.

If there was a worldwide slowdown in 1980-more likely it started around 1973 when productivity started slowing-it doesn’t explain why there has been increasing inequality in the US and Britain and not these other countries.

It seems that the Anglo countries have done better growth wise-though this is not true regarding Germany-but still had increasing income inequality.

So the average man in the street may well prefer to live in a country with a lower GDP or per capita rate but with a higher relative income.

2. March 2013 at 12:47

“Let’s assume that when I sell my house for a gain of $500,000 (a gain that is purely inflation), that number will accurately describe my economic situation, or “class”, not my consumption level of $100,000.”

But you sell your house to someone else. So the aggregate data will reflect someone with $500k (or at least a stream of consumption over 30 years) … what does it matter *in the aggregate data* that Saez uses if that house sale is ascribed to you as one-time income or to the buyer as long term consumption? Aggregating over millions of people who are at different points in their lives relative to a house sale should remove this effect in the time series. And not many people sell there house for $500k and don’t immediately consume some portion of that on a new house. (I’m not asking what I think is an impossible question to answer … there likely is a small effect, just not at first order in an inequality measure like the Gini coefficient. Are there other examples of common kinds of income that make seem to temporarily shift “class”?)

[I agree that the majority of the post-70s economic slowdown likely reflects much bigger economic factors than changes in the income distribution. I think inequality is a factor, just not the dominant factor.

Personally, I like Matthew Yglesias’s model where there is a lack of toleration of post-recession catch-up inflation after the 1980s has been the dominant factor. That would make sense across countries — a kind of group-think as central banks became inflation hawks … but I am open to other explanations.]

2. March 2013 at 12:53

I’m bashing income taxes, which are a moral and practical abomination.

They may be a moral abomination, but it appears to me that they sure are practical (from the collectors POV, at least). How would a progressive consumption tax be levied?

2. March 2013 at 13:32

You go from one sentence where you state you’re a utliitarian to the next where you express a very strong moral preference behind your opposition ton income taxes.

2. March 2013 at 14:31

@ Jake

For that to be even considered you would first has to show that given money to people in poor nations helps.

We have lots of data to show it actually does not help them.

Also as utilitarian grounds, you can not take a snapshot. For this to work you need a process, that process needs stable property rights and that does not go togather with ridistribution of income.

2. March 2013 at 14:47

Scott,

In a follow up to my previous comment I did a Monte Carlo simulation using a log logistic distribution for income. (I have odd hobbies.)

If you have a random subset of the population sell a house in a particular year (and gain income), this has no effect on the Gini measure of inequality if the house sale is proportional to the income (richer people have more expensive houses). The Gini coefficients for the original population and the population with house sales of up to 100,000X their income are the same when the probability of a house sale is 1% up to 50%.

I did get a big effect if the value of every house sold was the same and equal to some multiple of the median income … but that is to be expected as adding a constant to a random subset of the population decreases income inequality.

Basically, for your claim about house sales affecting measures of inequality to be true, the value of houses would have to have a distribution that is significantly different from the underlying distribution.

For your specific claim that the sale of a house somehow makes measured inequality worse than the underlying inequality it would mean that house values follow a significantly more unequal distribution — a significantly higher Gini coefficient — than income. The effect is approximately and admixture of the two distributions over the probability p of a person selling a house times the ratio of the population gini G and the house value gini H … G’ = p*H + (1-p)*G.

Since p is small (<0.1) and H is not very different from G, you end up with G ~ G' and no effect due to counting house sales as income.

2. March 2013 at 14:57

If the elasticity of taxable income reaches 0.92, the current US top rate is optimal under the Saez &Diamond’s JEP analysis. That is, if the elasticity numbers move up not a lot, Diamond has to advocate lower taxes for the super-rich!

Keane’s recent JEL survey explains why elasticities of labour supply increase ten-fold if on-the-job human capital accumulation is accounted for properly.

Diamond and Saez pass-over the optimal taxation of capital income being perhaps zero, or at least very low, by referring to administrative issues at the capital-income boundary.

Rawls was more awake to the power of incentives and advocated progressive consumption taxes because these taxes taxed what people take out of the common store of goods rather than what he or she contributes. Also not addressed by Diamond and Saez.

2. March 2013 at 15:05

Ceteris paribus Saez, ceteris paribus.

Decreasing the tax rates on the highest income earners cannot show up in observable data of higher subsequent growth unless everything else is held equal.

Good luck with that.

2. March 2013 at 15:08

Theo, No difference.

Nick, Maybe.

Jake, Maybe. Indeed immigration is better that redistribution from a utilitarian perspective.

Mike Sax, I addressed the argument he actually made, not the one you wished he’d made.

Jason, A new house is not consumption, it’s investment. Consumption is a flow of services from a house. The capital gains problem massively distorts income distribution data, as does lumpy income, and lifecycle problems.

Filipe, Several different ways–one of which is a progressive payroll tax. There are other approaches, such as VAT with a rebate so the poor pay nothing.

Jim, Good points. Yes, they don’t pay enough attention to the long run effects on human capital formation.

2. March 2013 at 15:10

Looks like Japan would have converged if it weren’t for their monetary malaise.

2. March 2013 at 15:34

Scott,

Saez makes two points among others: 1) the top 1% have captured a very large fraction of GDP growth in many advanced economies, but especially in the U.S. and U.K.; and 2) the large gains accruing to the top 1% haven’t produced widespread gains for the remaining 99%. Therefore, comparing U.S. GDP per capita with GDP per capita for other countries doesn’t really address Saez’ point.

Consider French case. Your graph shows the ratio of French GDP per capita to U.S. GDP per capita falling from about .85 in 1980 to about .75 in 2010. If, however, we exclude the income gains of the top 1% in both France and the U.S., then, according to Saez’s data, average incomes among the 99% in France grew by 26.4% between 1975 and 2006, whereas average incomes among the 99% in the U.S. only grew by 17.9% over this period.

I don’t have the data, but it would be interesting to see the U.K.’s GDP per capita growth performance for the 99%. In the U.S., the top 1% captured 58% of the total gain in income between 1976-2007. And although the top 1% share of total income in the U.K. is a little less than in the U.S., it’s grown substantially.

If, however, we leave aside the income gains of the top 1% in both France and the U.S., average real income per family in France grew by 26.4% from 1975 to 2006, but only by 17.9% in the U.S. over this period. See http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/02/what-does-economic-growth-mean-for-americans/

2. March 2013 at 15:37

I meant to delete the last paragraph except for the internet reference. Sorry

2. March 2013 at 15:44

“if that were the case, the growth in top incomes should not come at the expense of lower incomes and it should stimulate economic growth. The difficulty, however, is that if you look at the data you don’t see clear evidence that countries who cut their top tax rates and experienced a surge of top incomes did experience overall better economic growth.”

– It’s worth quoting this again to make it clear that Scott is NOT attacking a strawman; he’s disagreeing with a substantive point i.e. that the countries that cut income taxes dramatically don’t see much better economic growth.

Of course, whether and to what degree the growth of Britain and America since the early 1980s is due to income tax cuts is another issue. For example, there was a lot of regulatory-rent seeking and bad microeconomic policy in general that was done away with during that period, especially in Britain. Both countries also had more macroeconomic stability after the early 1980s, especially the USA.

2. March 2013 at 15:50

Greg Hill,

“captured”

What a bizarre choice of words. I didn’t know that wealth roams around or gets captured. I was under the impression that it had to be produced.

That’s quite apart from the fact that talking about “the 1%” as a group over a period of 30 is a statistically fallacious way of thinking, since that’s a statistical category with people moving in and out of it, rather than a group of particular people tracked over time.

2. March 2013 at 15:50

It seems to me there is a real opportunity for some smart economist to boost their reputation by writing a good book on the merits of having more rich people. (Maybe someone already has?)

My simple study concerns Microsoft. When I was a young person living in Seattle, Microsoft did not exist. Today we know that Microsoft has very much helped increase the ratio of rich people in the world. If you live in Seattle and see all the money flowing from Microsoft to employees, local businesses and local governments, you would be stupid if you did not judge the birth and growth of Microsoft to be a good deal for the average person, rich and poor alike.

2. March 2013 at 15:51

* 30 years.

2. March 2013 at 15:55

Bob O’Brien,

“But if you taxed Microsoft investors at 90% and gave the money to poor people in Seattle, then you’d have all that AND a better distribution of income.”

So much of this debate comes down to seeing profits as either (1) residual incentives for entrepreneurial actions; or as (2) an add-on cost to a given structure of production and distribution in the determination of prices.

Talking about “shares”, “capturing” and “the distribution of wealth” only makes sense in most contexts if one approaches a market economy using approach (2).

2. March 2013 at 15:56

(Obviously that was a hypothetical interlocutor, not what you actually said.)

2. March 2013 at 17:11

“The capital gains problem massively distorts income distribution data, as does lumpy income, and lifecycle problems.”

I did the calculation. These do not have an effect on the inequality measured with Gini coefficient unless they are taken from a separate distribution with a different Gini coefficient.

2. March 2013 at 17:30

Its interesting to see where people get in the mud with a guy like Saez. I started taking some notes during his presentation.

At 12:35 he is discussing a chart which shows how income of the top-1 is divided among business income, capital income, capital gains, and salaries. I don’t have much to say about the chart itself, but there is an issue with his narrative on this slide. He seems to think the increasing share of capital gains income at the end of the series has to do with hedge fund managers versus ‘retired business men’ and ‘legacies’ in the 1930s. He insinuates we should feel okay about the 20s, but not about today. The real issue is his story. It isn’t clear the composition of the 1% itself has become weighted by hedge fund managers on the basis of what he claims (rising capital gains income). Rather, the chart shows pretty clearly how the tax advantages of different types of income have shifted over time. It was once very favorable to hold a corporate shield around your assets. Thus capital income dominated business income and capital gains. That ceased to be true after ’85, and you see a shift starting there–S corps, LLCs, and partnerships became more tax efficient. Meanwhile, the high inflation 70s helped build critical mass behind reducing capital-gains rate, making that the preferred vehicle for distributing capital earnings. It has nothing to do with hedge funds.

17:00 He presents his time series graph and stakes the position that income share of the top-1 were depressed during the 1930-1980s because of progressive nirvana. Yet a more natural explanation is that the income of the top-earners disappeared from view but not from fact. Before the 1930s there was no reason to cloak your income. So income in available data appears high. Then the tax regime goes in and shelters became rampant, discussed widely and used widely. In the late70s and 80s there was big push to close loopholes and suddenly the income started to appear again. This process has continued through today. Really getting more and more onerous with time–let me say the FATCA rules which just went into effect recently is a nightmare (my spouse is a foreigner). As these rules go into effect, more and more income appears on the books of the top 1%. Note: this is just as much about changing the definition of income as it is about revealing hidden income.

He makes the claim that income tax rates are responsible for this process, but income tax rates have moved with loophole reform because tax reform has often been treated as a revenue neutral process. So the two aspects of the policy are conflated in time.

Again the simpler answer is that the single moving part: loophole closing/redefining income is the one that caused the change in income share.

Indeed, around 18minutes he does a comparison between the US and Sweden and France. I know a fair bit about both countries. Both countries are rife with tax shelters and a culture of concealing your income. In Sweden, finding ways out of tax is very socially acceptable. People swap tips. To the point where even very dubious schemes can be discussed without opprobrium

So then at 25 after, he gets to slide 18 and he reviews some explanations.

– taxes discourage work

– taxes are avoided

– rent seeking

Under taxes are avoided he suggests we should focus on closing loopholes then raising taxes. Of course this whole time we have been closing loopholes. That’s why we see the share of the top-1 go up so much. He says once we do this we should raise taxes to reduce inequality.

This gets to his error in the earlier slides. Raising taxes won’t change inequality. The inequality is constant, only the appearance of it changes as loopholes are opened and closed. (Probably there are some supply slide effects and the incentive to cheat is correlated with rates, so tax cheating is an issue even after the legal tax loopholes are closed).

So his three scenarios are not complete, but he thinks they are.

At 29 minutes after, he assumes that the only way for tax evasion to be the story is if they depend primarily on the rates. As I said, the issue is not the rates so much as the existence of legal loopholes.

Around 32 minutes after, he has the whooper that tax-evasion cannot be the issue since the top-1 give more to charity now than they did before, they must be “richer”. Yes they are richer, but also richer in absolute terms (GDP/capita growth), so this does not then imply that they must be richer in relative terms too.

Around 33 minutes he presents a slide strongly supporting the evasion hypothesis without realizing. It shows the top-1 lagging behind, then catching up. That is consistent with the income being revealed and having always existed. Basically the implication of that slide is that the bottom-20 and top-1 have been growing at the same rate this whole time. So his claim that there is a contradiction in the common idea that growth lifts all boats, is not supported by his presentation. Growth does lift all boats, if you assume rampant evasion/ in the 50s/60s/70s.

2. March 2013 at 17:53

W. Peden,

“Captured” wasn’t the best choice of words, but that’s not to concede that high incomes are always the fruits of productive labor, excellent foresight, risk taking, etc. Didn’t fraudulent lending and cozy relationships with the rating agencies allow the sellers of mortgage-backed securities to “capture” a lot of income? Or, would you insist this income was “produced”?

Perhaps you’re uninterested in the distribution of income, or regard it as the product of free exchange, pure and simple, but the question raised by Saez is whether the large share of income going to the top 1% in the U.S. and U.K. has paid dividends to the 99%. The fact that the 1% is a statistical category rather than the same group of individuals over time isn’t really relevant to the issue of whether the increased inequality of income in the U.S. and U.K. has improved the lot of the 99%.

2. March 2013 at 19:34

in general, I am a free market libertarian.

Like everyone I know, I fail my ideology at some point.

Ask any female libertarian, for example, should we legalize polygamy and open-air prostitution………should your neighbor be able to convert his house into a brothel with blinking lights and plate-glass windows….soon, there are no more libertarians….

I get “weak” when the topic of national parks comes up. I love our national parks…

And I wonder this: If free markets lead to greater concentrations of wealth and income, continuously, are they best?

Of course, concentrations of wealth and income lead to political power, and leverage over regs and taxes.

In the real world, that will lead to plutocracy.

Libertarians can counter that is best solved by the smallest government possible—but the wealthy and powerful might like a larger government, as long it does their bidding. (Like we have in the USA?)

So it comes back to this and the question so many economists ask:

“Democracy, and attendant egalitarian policies may work in practice, but more importantly, do they work in theory?”

2. March 2013 at 20:08

“It’s worth quoting this again to make it clear that Scott is NOT attacking a strawman; he’s disagreeing with a substantive point i.e. that the countries that cut income taxes dramatically don’t see much better economic growth.”

What was Saez’s substantive point?

“However, if that were the case, the growth in top incomes should not come at the expense of lower incomes and it should stimulate economic growth. The difficulty, however, is that if you look at the data you don’t see clear evidence that countries who cut their top tax rates and experienced a surge of top incomes did experience overall better economic growth.”

So, we can infer from this that Saez is equating income equality (or at least an absence of income inequality) with “overall better economic growth.” I would assume to determine this we would look at median incomes, gini coefficients between countries, income quintiles, or some other measure of income distribution.

What does Sumner use? An economic wide metric that is ineffective in measuring income distribution.

Pecurliar, though, that when we use an economy wide metric like GDP per capita and compare that against median family incomes in the U.S., they track one another quite well until the late 1970s and 1980s. (Lane Kenworthy has an article on this)

http://lanekenworthy.net/2008/09/03/slow-income-growth-for-middle-america/

After that point, GDPpc and MFI split, with the former outpacing the latter indicating a widening income gap. In other words, we saw over all economic growth, but it was not evenly distributed across income levels. What changed in that period? The resurgence of supply side economics.

2. March 2013 at 21:04

Income distribution data must be handled with great care:

– The US has worldwide income taxation based on citizenship, most other countries base taxation on residence. US income taxes are on the low side by OECD standards (but the US gvt provides a lot less as well). Rich Americans have many ways to reduce their taxes legally.

– Differences between European countries should take into account that seriously rich Europeans will move to more attractive jurisdictions next door, plus that the practice of illegally escaping taxation is widespread despite recent attempts to improve tax access to accounts in Switzerland, Luxemburg etc.

– The peculiar forms of domicile and residency of the UK make the UK a very attractive tax haven for wealthy non-brits. The presence of several hundred rich Greeks, Russians and sub continentals (who all pay a little on their UK-derived income and are thus in the income tax statistics).

– Large informal sectors in some economies (organized crime, construction, drug production, hospitality) may produce seriously rich people.

So, what have we got: rubbish in, rubbish out.

International comparisons with income distribution as an explanatory variable deserve prima facie distrust. As do similar discussions of minimum wages…

American scholars may be the least qualified to understand the top end of income distribution data and only marginally less qualified to generate intuitions about causes and effects in this field.

2. March 2013 at 21:06

I’ll address the comments tomorrow, but I can see that some people don’t understand how blogs work. A blog post is not a dissertation. If I or any other blogger comments on a particular assertion made by someone else, we are under no obligation to drone on for 20 pages discussing every point in the paper. That’s what academics do, not bloggers.

I have other posts discussing other assertions by Saez that I disagree with. I even linked to one in this post. You are free to examine those other posts. Every other blogger, including those on the left who agree with Saez (like Krugman) often point out a particular argument in a paper that they disagree with. If you don’t like that style, you shouldn’t read blogs. So don’t come over here and tell me what his “real point is”. I can discuss any point I wish.

So what if Saez was interested in income distribution–I said I agreed that the tax system should redistribute income. Why should I discuss something I agree with?

And why do I keep ending sentences with prepositions?

2. March 2013 at 21:21

Germany, eh? Reminds me of this recent article in Businessweek, “In Germany, the company car is a Porsche.”

And yes, it’s treated somewhat as income, but in an odd tax treatment that undervalues the income and ends up costing employees much less than it would cost to lease the same car. And in Germany the company car can be used freely for personal use, the article claims, whereas one of the big tax changes in 1984 made it harder to get away with personal use of a company car without valuing it properly.

As said above, tax law changes designed to reduce loopholes and make more income at the high end reported, but with lower tax rates, made more income reported. How much of that is actually inequality is a different question.

Hewlett-Packard used to own a 500 acre campground and retreat site. I doubt that was counted in the income statistics.

2. March 2013 at 21:34

Benjamin,

Two conscientious and yet reasonably successful politicians (Bismarck and Lee Kuan Yew) were not in favour of democracy (yet Bismarck was a pioneer in lots of things democracies need, and he expanded the franchise as well). In fact, during the heyday of Anglo liberalism, there was no question that the whole population should have a vote in the affairs of state. Unfortunately for them, democracy is difficult to deny to large groups of populations if they are organized (like by unions) and they want it, but not to groups with little power (remind US franchise excluded a certain racial minority into the post WWII years and many people did not have a problem with that; the ueber democratic Swiss have long excluded women from the vote, etc). Read the Greek classics about the democratic experiment in Athens and a handful of other city states.

But we have it. It may not be qualitatively stable (changes in media, gerrymandering, dynasties like in Japan, vote buying, etc) and it may require a dose of optimistic idealism that tends to last only a few generations. So we will see. The interesting part is that most “progressive” movements of the past half century: Greens, gender politicians, tend to be at odds with libertarianism, just like the socialists and robber barons were.

You ask questions that are outside economics. We simply assume that growing GDP is good and look at choice situations through the lens of cost-benefit, where stakeholders sets are assumed to be definable and stakeholder preferences are supposed to be known.

I guess economics should not try to answer moral, legal or political questions, and rather stay fairly abstract, a fascinating branch of applied mathematics, axiomatic, that may inspire policymakers, but not guide them unless the unavoidable reduction (of reality, whatever that may mean) of economics approaches the consensus reality of all relevant stakeholders. Economists are natural utilitarians but they should control their urge to let their toy trains carry real freight. The old Soviet planning economists were an extreme case of economists (you might not call them that but they were) determining the economy, with only little guidance from politicians. They were clearly aware of the limitations of their craft but hoped that more powerful computers and more data (higher resolution) would lead to better results.

Discussions like the one highlighted here by Scott are an excellent illustration of the limits of economics (or social science in general)

There is of course an excellent utilitarian approach to evaluating legal structures and solutions by people like Posner. But that approach has little traction outside the US.And the crazy thing is that most of Posner’s work, on for instance tort, confirms that the common law is pretty close to a utilitarian ideal.

2. March 2013 at 22:40

Dear Commenters,

Please see this awesome post by Prof. Sumner on Iceland:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=8702

Could someone point me to good resources that support this story? In particular, statistics that show collapsing financial sector employment and booming technology / manufacturing employment within a short period of time?

Remarkably, Iceland’s president said that exactly that process happened “within six months.” I’m sure there’s something to this story. It would just be nice to see data that substantiates it.

http://read.bi/VfRcWV

3. March 2013 at 02:13

[…] [source] […]

3. March 2013 at 04:37

Greg Hill,

“Didn’t fraudulent lending and cozy relationships with the rating agencies allow the sellers of mortgage-backed securities to “capture” a lot of income? Or, would you insist this income was “produced”?”

If that’s how you’re using the word ‘capture’ (i.e. fraud), then it is all the more inaccurate and inappropriate to use it to describe the incomes of a large group of people.

If there was fraud, then there was fraud. We don’t even NEED to use the word ‘capture’ here, since we have a perfectly good category for actions like fraud: crime.

3. March 2013 at 15:37

Greg Hill, You said;

“Consider French case. Your graph shows the ratio of French GDP per capita to U.S. GDP per capita falling from about .85 in 1980 to about .75 in 2010. If, however, we exclude the income gains of the top 1% in both France and the U.S., then, according to Saez’s data, average incomes among the 99% in France grew by 26.4% between 1975 and 2006, whereas average incomes among the 99% in the U.S. only grew by 17.9% over this period.”

Both of those numbers can’t be right, or else the discrepency occured in the late 1970s–before Reaganomics.

Jason, The Gini for consumption (which is what matters) is much different than for income.

Jon, Good points, that’s why I focus on consumption inequality.

Jerisdebtor, Where did I misrepresent what Saez said? I quoted him exactly, and responded to exactly what he said.

3. March 2013 at 18:25

Scott,

You write, “Both of those numbers can’t be right, or else the discrepency occured in the late 1970s-before Reaganomics.”

The numbers in question are those from your graph showing that real GDP per capita grew faster in the U.S. than in France between 1980 and 2010; and Saez’s data showing that, if the income of the top 1% in both countries is excluded, then the average real per capita income among the remaining 99% grew faster in France than in the U.S. between 1975 and 2006.

I think both sets of numbers could indeed be right. For example, suppose real GDP per capita grew by 40% in the U.S., but only by 30% in France. Suppose 60% of the total income gain in the U.S. was concentrated in the top 1%, whereas only 20% of the total income gain in France was concentrated in the top 1%. In this case, average per capita income among the 99% would have grown faster in France than in the U.S. Am I missing something?

3. March 2013 at 19:40

Rien-

Thanks for your comments, I hope you are still reading.

I actually favor democracy, and think it is the end of policy, not the means. I would rather live in a democracy at 90 percent of GDP, than an unfree state at 100 percent of potential GDP

My point was this: If free markets lead to ever-increasing concentrations of wealth do we want free markets? And, even then, won’t such concentrations of wealth inevitably lead to outsized political-economic power?

Scott Sumner recently posted about 55 cents an hour wages in Germany. I confess, that shocked me. I love national parks, and I will admit “saving” architectural gems.

I guess I am admitting that free markets and libertarianism don’t work in some situations. So, it just becomes a argument about when they don’t work.

3. March 2013 at 21:15

Greg Hill:

I think you’re making a sound argument. The math makes sense.

3. March 2013 at 21:41

Benjamin Cole:

“Scott Sumner recently posted about 55 cents an hour wages in Germany. I confess, that shocked me. I love national parks, and I will admit “saving” architectural gems.”

“I guess I am admitting that free markets and libertarianism don’t work in some situations. So, it just becomes a argument about when they don’t work.”

It is not a valid argument to claim that if the free market doesn’t give you what you want, that the free market “doesn’t work.”

I want to eat food that will allow me to live to 1000, and I want a cure for cancer, and I want to be able to teleport to anywhere in the world at near lightspeed. Oh no! The market isn’t giving me what I want. Does this mean that I am right to claim that the free market doesn’t work? No, because I’m not the only person in the world with preferences.

The free market works at allowing people to receive what other people are willing to give and on what terms. It is a social concept, not a “Benjamin Cole” concept only.

If you think the market “doesn’t work” when it doesn’t give you the national parks and state buildings you want, then you just opened up a can of worms and must accept that the market doesn’t work when it doesn’t give others what they want because the resources were tied up in building what you want.

4. March 2013 at 00:57

Benjamin,

Still reading. I like this topic. You said:

“I guess I am admitting that free markets and libertarianism don’t work in some situations. So, it just becomes a argument about when they don’t work.”

Also an argument about what it means for markets etc to “work”. Democracies tend to be biased towards distribution rather than growth/efficiency. Democracies that distribute a lot and are small and open, and rely on progressive income taxation, lose the loyalty of the wealthiest citizens. They leave, cheat or lobby for breaks. In all cases investment by the richest is based on distorted incentives. Democracies that distribute much less have a problem with the below median voter. So unless the poorer voters are discouraged etc so they underrepresent in elections, there is a problem that democracies find hard to fix. Libertarianism has no solutions for that and free markets are not appealing enough to most voters (as evidenced by the preponderance of gvt activity distorting markets rather than making them freer, except in times of crisis, like when the Eastern Europeans were liberated and became democratic)

But these are political issues where the economist can have a supporting role. But if the people are sovereign, they have the right to be inefficient.

4. March 2013 at 03:21

Geoff,

“It is not a valid argument to claim that if the free market doesn’t give you what you want, that the free market “doesn’t work.””

Quite right. As Rothbard pointed out, the free market is no guarantee against the bad things of the world, including bad people; nothing is. It is possible under just about any social system that the entire population will have a fit of madness and commit suicide, yet we don’t hold this against these systems.

55 cents an hour looks a lot better when you consider Germany’s recent labour market performance. Some people manifestly can live on that kind of wage in Germany and they are free to choose to work rather than be idle, which is a good thing.

4. March 2013 at 07:57

Greg Hill, I should have been more specific. I realize they can both be right mathematically, my point was that the income gains by the top 1% would be implausibly larger in the US than France, based on my common sense knowledge of the woirld. Either they use different techniques, or much of the difference occurs in 1975-80 (before France entered its permanent recession.)

Ont thing that puzzles me about people who like the French model is that they are also people who tend to worry about unempoloyment. But France has had high unemployment since the early 1980s. They do have more generous unemployment programs than we do, but surely that’s not an adequate answer. You often see the unemployed in Paris’s suburbs rioting over economic conditions.

I would add that France is poorer than America, and the gap is widening.

4. March 2013 at 20:45

Scott,

Thanks for taking the time to reply. I know you’re busy and I really do appreciate your responses to comments. Nevertheless . . .

You write, “my point was that the income gains by the top 1% would be implausibly larger in the US than France, based on my common sense knowledge of the world.” I love your posts and admire your work, but your “common sense knowledge of the world” regarding the 1% share of total income gains in the U.S. vs. France isn’t a compelling argument, especially insofar as the point of Saez, et al, is to challenge the prevailing view that income gains are fairly widely shared.

You go on to say, “I would add that France is poorer than American, and the gap is widening.” Here again, it’s important to consider the distribution of wealth in the two countries. Based on a recent Credit Suisse study, median (not average) household wealth was quite a bit higher in France than in the U.S. as of 2011. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2012/07/18/are-canadians-richer-than-americans/

I’m not so much a fan of “the French model,” in this context, as I am a critic of cross-national comparisons based on GDP and Wealth per capita without regard to its distribution (and, in the case of the French in particular, without regard to trends in hours worked per employee).

5. March 2013 at 03:34

“Would a response from Saez be that most of the additional gdp per capita is gobbled up by those on higher incomes in the UK and US.”

That would not be my personal experience in the UK, throughout that whole period. The comment in the article about the “catching-up” with the US is accurate, and the chart vividly shows how disastrous economically was the politics and government of the 1960s and 1970s (which also chimes with personal experience for the latter years).