Stop obsessing over interest rates

I have a new Mercatus working paper explaining why monetary economics needs to stop focusing on interest rates. Of all the economics papers that I have written, this one best captures how my view of monetary economics differs from the mainstream. Here is the abstract:

In recent years, Keynesians and NeoFisherians have debated whether a low-interest-rate policy is inflationary or disinflationary. Both sides are wrong; interest rates are not a useful indicator of the stance of monetary policy. Some contractionary monetary policies lead to lower interest rates, while other contractionary monetary policies lead to higher interest rates. Instead, economists should use market expectations of inflation, nominal GDP growth, or both to measure the stance of monetary policy. Furthermore, the Fed should no longer target interest rates.

There’s no math because all I really do is use off the shelf concepts like the interest parity condition, Dornbusch overshooting, and the Fisher effect to look at interest rates from a different perspective. I’m not trying to re-invent the wheel, just show that the wheel needs to be re-aligned.

Most economists will probably hate this paper. But if there are a few younger readers that get something out of it, I’ll be happy. Maybe one of them will rewrite the paper using math.

BTW, John Cochrane has a new post that reconciles the Keynesian and NeoFisherian views of interest rates. He suggests that perhaps higher interest rates are disinflationary in the short run and inflationary in the long run—basically Milton Friedman’s view. Here’s Cochrane:

Reconciliation:

In sum, once we include a multitude of plausible fractions that send inflation temporarily the other way, including the long-term bond effect and household financial frictions, a negative response to temporary interest rate rise like Sweden is consistent with a neo-Fisherian prediction that in the very long run higher interest rates produce higher inflation, and thus also consistent with the lack of a spiral at the zero bound.

But I move somewhat in Lars’ [Svensson] direction. Just how relevant is this observation to policy? When the central bank can move interest rates, it may well want to push rates around by exploiting the temporary negative sign. “Temporary” can be a long time. Even if the long-run effect is positive, the central bank may move inflation up more quickly by lowering rates, pushing inflation up with the short-run negative effect, and then then quickly getting on top of inflation. Which is just what central banks classically do, and exactly what they do if the economy is unstable as well. They may never notice the positive possibility, and may never have the patience to wait for it. Thus, the neo-Fisherian possibility may be completely irrelevant in normal times.

But when the central bank cannot lower interest rates, then the slow, preannounced, persistent, we-wont-give-up, and whatever else needed to overcome or wait out temporary forces in the other direction, may still be a useful policy for liftoff. One might indeed read the US interest rate increases — known years in advance — in that light.

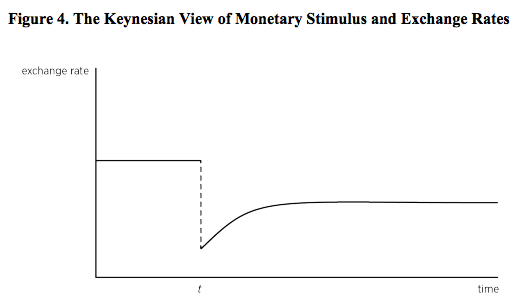

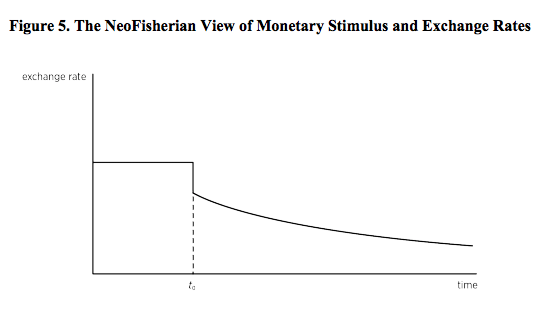

That’s plausible, but it’s not my reconciliation. I believe that monetary stimulus can either raise or lower interest rates even in the short run, as the following two exchange rate graphs illustrate:

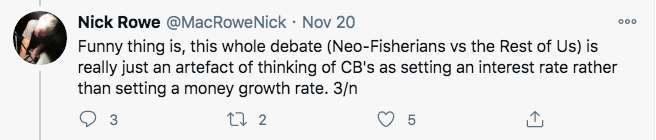

PPS. I said most economists will hate my paper. Nick Rowe is one possible exception. Here he comments on Cochrane’s post:

Or setting the exchange rate growth rate. Or setting the TIPS spread. Or setting the NGDP futures price growth rate.

Please, anything but interest rates.

Tags:

24. November 2020 at 08:10

Thanks for directing me to the paper. I’ll give it a read as a non-economist and hope to understand the major points. Any comments on Janet Yellen as Sec of Treasury? It looks like Biden is picking reasonable people and it’s no surprise to see the anti-China Republican Congressmen already start to pile on. I guess they don’t believe in international trade any longer.

24. November 2020 at 08:46

Good piece.

24. November 2020 at 08:53

Correct, we all should stop worrying about interest rate policy because it doesn’t exist. This policy is done by a person called Mr. Market.

24. November 2020 at 08:57

– Rising interest rates are Deflationary and falling interest rates are Inflationary. And I have seen only a very few people who understand this concept. The followers of the nutty monetarist and the austrian school are NOT among those.

24. November 2020 at 10:14

Thanks for the paper. I have been following your blog for a long time, and I have to say that you have a great influence on my view of the economy. I was 15 when I started interested in economics, today I am an undergraduate student(in Turkey).

Frankly, every day I am realizing the problems in mainstream academics. Speaking about my own country, at first, it seemed strange to me that academicians were so obsessed with interest rates. But later I realized that this was a general problem. Therefore I felt I have to write something about market monetarism in the Turkish language(there is almost no content on market monetarism in Turkey). All of this happened thanks to the fact that you impressed me when I was 15 years old.

As I see in Turkey and Twitter, especially the market monetarism is gaining popularity among the liberal/libertarian youth(in classical terms). I am hopeful for the next generation of market monetarists, and many young economists can turn your building into a skyscraper. That’s why the papers you write are important for young market monetarists like me.

24. November 2020 at 11:47

But Cochrane still uses the language of causation: “…in the very long run higher interest rates produce higher inflation.” That wasn’t Friedman’s view was it? His view was that causation went the other way – that high inflation (produced by high money growth) produced high interest rates. The fact is that other things being equal, if all the central bank did was raise its short term policy interest rate to the point where it caused an immediate disinflationary effect and kept it there, we would get a disinflationary spiral, no long run increase in inflation. I think you are too generous to the Neofisherians because you agree with the long run correlation between nominal rates and inflation due to both being driven by the growth in the money base. But that’s not a causative relationship between rates and inflation per se and therefore not a scientifically meaningful one.

24. November 2020 at 12:10

@Willy2: “Rising interest rates are Deflationary and falling interest rates are Inflationary.”

False. To quote Sumner, “never reason from a price change”. Interest rates are the price of credit. You can conclude nothing from a change in the free market price of credit, if you don’t know why the change occurred. Depending on the underlying cause, any combination of rising or falling with deflationary or inflationary is possible.

24. November 2020 at 12:16

Hey Scott, off-topic and maybe a post on this is coming, but do you have any thoughts on Yellen’s claim that the 2015-2016 “overtightening” on monetary policy had minimal impact on growth? She is becoming more prominent as a nominee for Secretary of the Treasury, and it seems like this is a criticism she is having to defend against despite being well-liked. For all Powell’s failings, I would rather have him than Bernanke (too cautious) or Yellen (failed to corral the hawks).

24. November 2020 at 13:39

Scott,

Isn’t it really a problem of age? People over a certain age are terrified of inflation. So the fed is so scared that they might “push” too hard and we are all pushing around wheelbarrows full of cash to by bread.

So you end up with the ridiculous spectacle of the fed forecasting that it won’t meet its own targets for gdp or price growth.

Clearly the fed has all the power it needs to move interest rates or monetary growth or inflation…all it takes is courage.

I remember James Hamilton writing about this after the great recession. I don’t remember the exact wording but it was something along the lines of;

A. send everyone a check for some large amount of money (a million?)

B. buy all the stock for sale on all the stock exchanges.

etc etc…I guarantee that somewhere along the way there will be all the inflation you want.

24. November 2020 at 15:15

Boring. Wake me when Sumner writes a paper that assumes, as is in fact the case, money is both short-term and long-term neutral. Bernanke wrote an econometrics paper around 2002 that showed money is largely neutral (a mere 3.2-13.2%, out of 100%, change is attributed to Fed policy changes, statistically significant but hardly worth talking a bout).

24. November 2020 at 16:17

I thought about this really hard and for a really long time. I think modern macroeconomists are missing something, often because they have a political bias that compels them to think along certain lines regarding monetary and fiscal policy, or because of professional conventions.

We live in an age of (mostly) digitized cash and also globalized capital markets.

If you want nominal GDP to expand in a year within Nation A, you must expand the amount of digitized (and paper) cash spent in that year within Nation A.

My guess is if you told conventional macroeconomists that unless nominal GDP increased by 5% in Year One in Nation A they would be guillotined, then even conventional macroeconomists would propose money-financed fiscal programs.

Maybe even Scott Sumner would prefer not to face the guillotine.

Trying to adjust nominal GDP solely through the Rube Goldberg-contraption called the Federal Reserve, and thus through the clap-trap of commercial bank lending, and while international capital markets toss trillions of dollars hither and yon across national borders, strikes me as a very difficult process.

Why make life more complicated?

24. November 2020 at 17:31

Alan, She’s fine. It doesn’t really matter who Biden picks.

Thanks Kgorgen, That’s good to hear.

Rajat, I’m not sure exactly what sort of causation Cochrane is claiming. I sort of assumed that he meant that a monetary policy that produces high interest rates in the long run will also produce high inflation in the long run. When people “reason from a price change” their statements are hard to interpret.

derek, It’s hard to know for sure, but even a small effect might have been enough to cost Hillary the election. I commented on this point over at Yglesias’s new blog.

robb, Yes, debasing a currency is easy. Even Zimbabwe can do it.

24. November 2020 at 20:20

Scott, central banks seem to fret a lot a lot about the zero bound of interest rates and are willing to consider interesting steps to avoid that perceived problem.

But do you know why they never seem to consider just targeting long term interest rates instead? In the most extreme case, target interest on consols, ie eternal annuities, but even just targeting the interest on the longest running government debt in wide circulation seems fine?

I am with you that targeting ngdp futures or TIPS spread etc is better. But that seems to radical for some central banks. So I am just trying to understand why the central banks don’t seem to even consider this rather small change?

24. November 2020 at 20:57

money is neutral, as ray always reminds poor desperate thinker manque sumner, if it is neutral; manipulated, it is not. what isn’t, is politics, which is all the pseudo-science of economics can ever hope to be, justifying using neutral money is non-neutral ways to immiserate the masses. the only honest thing fabian keynes ever said was “in the long run we’re all dead”, other than not now….

24. November 2020 at 21:06

@Benjamin Cole: “Trying to adjust nominal GDP solely through the Rube Goldberg-contraption called the Federal Reserve, and thus through the clap-trap of commercial bank lending”

No. Monetary policy works primarily through (expectations, and then) the hot potato effect. Commercial bank lending is not a significant part of the monetary policy transmission mechanism. Monetary policy would work just fine in a hypothetical economy with no banks and no commercial lending at all.

Your focus on interest rates and commercial bank lending is causing you to completely misunderstand monetary policy.

25. November 2020 at 00:09

Don Geddes–

Oh, Heavens-to-Betsy, I understand steaming tubers.

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/tag/hot-potato-effect/

This blog by Marcus Nunes still works well. I used to co-author a that blog with Nunes.

But…you run into a some problems.

Call me “Mr. Concrete Stepps Head.”

One is, no one seems to believe the Fed—-for decades and decades the financial smarties warned of higher rates of inflation and interest rates threatening ruin. I mean, for like 40 years—read Martin Feldstein or Paul Volcker from the day.

So expectations were for Fed-induced higher inflation…but inflation came down. So what do expectations result in?

Expectations have the power of Gilligan’s Island rerun.

A second problem is the globalization of capital markets. We have multiple major and several minor central banks operating upon the global money supply simultaneously.

If we have a global economy, then to which central bank to you genuflect?

A third problem is even the “inflation expectations” idea has to work through the channel of bank lending, as most money creation is endogenous. If banks do not lend, you are going to see a slowdown in the economy. So, even red-hot tubers are dependent on the good graces of bank-loan officers.

In the end, I say just do the money-financed fiscal programs.

A great way to MFFP is a holiday on Social Security taxes, offset by direct money-printing by the Fed, which sends the digital loot to the Social Security Trust Fund.

25. November 2020 at 00:47

For ‘information’?

” Guidance of bank credit is in fact the only monetary policy tool with a strong track record of preventing asset bubbles and thus avoiding the subsequent banking crises. But credit guidance has always been undertaken in secrecy by central banks, since awareness of its existence and effectiveness gives away the truth that the official central banking narrative is smokescreen.'”

https://professorwerner.org/shifting-from-central-planning-to-a-decentralised-economy-do-we-need-central-banks/

25. November 2020 at 04:16

Just popping in to say how funny it is to see Ray Lopez trying to summarise basic statistics from an academic paper. Would love to see your whole discussant’s presentation Ray!

25. November 2020 at 06:05

https://twitter.com/ManishaKrishnan/status/1331346406532124675?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1331385195262595073%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es2_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.infowars.com%2F

Random house management under pressure from communists after agreeing to publish Jordan Peterson’s new book – a psychologist, and revered academic, with 10,000 citations.

Wake up folks. They are coming for you.

25. November 2020 at 08:44

Matthias, They don’t think that would solve the problem. I suppose they’d point to countries where long term rates are zero or even lower.

25. November 2020 at 12:51

Of all of this, the most mysterious part is what a “stance” is. I understand what a target is. I understand what an instrument is. But what is a “stance?”

25. November 2020 at 15:22

The most important line in Scott’s paper is on page 18:

” the rental cost of base money (interest rates)”

I.e., interest rates are NOT the ‘price of money’ in the same sense that $50 (or whatever) is the price of a barrel of Saudi oil. In this case the transaction is an exchange of ownership. Neither party is obligated to return the proceeds to the other.

The purchase/sale of a bond is different. It’s a loan, not an exchange of ownership. The seller of the bond is a borrower (renter of money, for a period of time), the buyer of the bond is a lender who has a legal right to the return of his money. Just like an owner of an apartment building has a right to the return of his real estate after the lease expires.

Interest on a loan is the rental price of money, not the buying price of money. The two prices often move in opposite directions, which is why Friedman, Bernanke et al say that interest rates are not a reliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy.

It’s amazing that any economist (like Walter Heller in his 1968 debate with Friedman at NYU) doesn’t understand this distinction. But, I know from personal experience that most economists do not.

25. November 2020 at 17:22

Thomas, Let’s assume the target is 2% inflation. Let’s assume the instrument is the fed funds rate. Then an expansionary policy stance is a setting of the fed funds rate expected to produce above 2% inflation, and a contractionary policy stance is a setting of the fed funds rate expected to produce below 2% inflation.

Patrick, Unfortunately, I suspect you are correct about most economists.