Simon Wren-Lewis on the British stagnation

Nick pointed me to a Simon Wren-Lewis post that does a great job of illustrating the British predicament in three graphs.

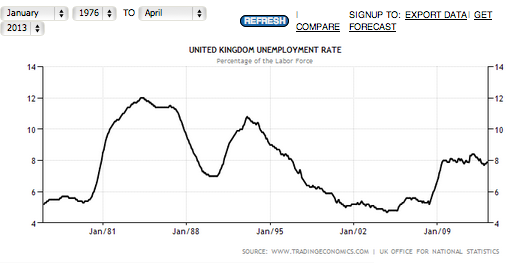

The first shows that British RGDP is lower than the levels of 5 years ago. The second shows that British labor productivity has fallen about 15% below trend since 2008. And the final graph shows a rise in unemployment, which is currently 7.9%. Wren-Lewis speculates that the elevated unemployment rate reflects a demand shortfall. I tend to agree, with reservations.

Unfortunately we don’t know the natural rate of unemployment in Britain, or even whether the natural rate is stable. If you take the longer view, it’s pretty obvious that the natural rate is not stable over time.

We also know that other European countries (notably France) have seen huge increases in their natural rate of unemployment since 1980. And we know that the size of the UK government expanded sharply after 2000, from about 37% of GDP to the high 40s. Note that the expansion was larger than the data suggests during the good years (2000-07) and smaller than the data suggests during the bad years (2008-12.) That’s because government spending should normally fall as a share of GDP during expansions, and rise during recessions. Thus the rise during 2000-07 is far more significant than many assume. This might have boosted the natural rate of unemployment, at least slightly. Note that unemployment rose 0.8% between 2005 and late 2006, a pattern that is highly unusual for an expansion, even given the slow RGDP growth.

Here I’d like to make the assumption that is most favorable to the Keynesian view; a stable natural rate that is lower than the actual unemployment rate during most years. Something in the 5.4% to 5.9% range. Anything much lower would imply that unemployment is consistently above the natural rate, which would of course be inconsistent with the natural rate model. Then the current unemployment rate is probably 2.0% to 2.5% above the natural rate, which suggests that high unemployment has depressed output by 4% to 5%.

To summarize, if we make the most Keynesian assumption that is plausible, a low natural rate of unemployment which has not been rising, and if we assume that 100% of unemployment is due to a demand shortfall, and if we assume that unemployed workers are just as productive as employed workers (no ZMPers), then it still appears that the recent British stagnation is 75% to 80% supply-side and 20% to 25% demand-side.

In other words, when Keynesians blame the slow British RGDP growth on the mythical “austerity” they are talking nonsense. This is partly because the unemployment numbers suggest that the British economy does not have a particularly large output gap, when compared to other developed economies, which means their massive budget deficit (trailing only Egypt and Japan) really does indicate a fairly expansionary fiscal stance. And second, because even if fiscal policy is quite austere, the slow RGDP growth is mostly due to supply-side factors such as declining North Sea oil output, less froth in high finance, and perhaps other factors such as labor shifting out of home-building. (I’m open to suggestions.)

Let me end on a positive note, by pointing to some areas where I agree with Wren-Lewis:

1. I agree with his claim that slow nominal wage growth suggests the elevated unemployment is mostly due to demand-side factors.

2. I agree that demand stimulus is appropriate, although unlike Wren-Lewis I’d rely 100% on the BoE. Ed Balls made things much harder for the BoE when he opposed changing their 2% inflation target. His comments were disgraceful, as one reason the government is reluctant to do more monetary stimulus is fear of being hammered by Labour on the “inflation” issue.

3. I agree with Wren-Lewis’s claim that NGDP targeting is not always optimal. I’ve argued (for instance) that the monetary authority could do a bit better by targeting NGDP net of indirect business taxes. Because these taxes rarely change significantly in the US, (which lacks a VAT) I tend to gloss over this problem. And there are a few other potential problems with NGDP targeting, especially in smaller and less diverse economies. But NGDPLT is a vast improvement over IT.

HT: Bill Woolsey

Tags:

29. April 2013 at 06:04

You have certainly convinced me, a left-leaning non-economist. The British case is certainly quite different from what we are witnessing elsewhere.

But I wouldn’t be so harsh on the BoE. They have taken far more aggressive than most other central banks. They have held the official bank rate at 0.5% and did quite a bit of QE event though CPI-measured inflation was a lot higher than in other countries. Core-CPI rose at a 3% compound rate since 2008, almost double the US rate. (I agree that inflation is not a good aggregate-demand indicator, but I think it does put the BoE decisions in context).

If the ECB and the Fed (and the BoC) had been willing to accept such core-CPI inflation, the global economic downturn would probably have ended some time ago.

29. April 2013 at 06:09

Imagine producers building weapons of war now which raises RGDP by X% now, thus making it impossible for them to build civilian goods with those resources to be available later on. Now imagine producers thinking about civilian uses for those scarce resources now, which does not raise RGDP by X% now, thus making it possible to build civilian goods later on. Which is more optimal? According to MM/Keynesian reasoning, the militaristic country is better off, because RGDP is higher now.

Now instead of imagining producers producing weapons of war, think of goods that consumers don’t want later on, but want now, such that it is reflected in consumer’s actual spending habits. Would it be more optimal for producers to try and produce those future goods anyway, or would it be more optimal for them to think about it more, thus bringing about a lower RGDP? According to MM/Keynesian reasoning, it would be more optimal for producers to start producing more future goods now, for the sake of achieving a greater RGDP now.

—————-

“Ed Balls made things much harder for the BoE when he opposed changing their 2% inflation target. His comments were disgraceful, as one reason the government is reluctant to do more monetary stimulus is fear of being hammered by Labour on the “inflation” issue.”

Yeah, damn him for telling the truth about price inflation. It’s better for politicians to pretend it isn’t happening, and hope that the hapless portion of the population who have to pay higher prices and experience a decline in living standards, blame greedy producers.

29. April 2013 at 06:44

Geoff:

You don’t even understand the basics.

You are confusing real GDP with the production of consumer goods.

A country that produced fewer military goods now, and instead produced capital goods, including partially finished goods, stockpiles of materials or anything else that would help produce consumer goods later would have the same real GDP.

It is probably the case that RGDP fails to property account for depletion of nonrenewable resources, but that is about it.

An obvious failue of RGDP is that if people decided that they would be happier working only 4 days a week, and spent the extra day in fun recreation, which they value more than the present and future consumer goods and services they give up, then RGDP would fall, (alot) but happiness would rise because of all the vaulable free time.

Conversely, if the government mandated everyone work 6 days a wekk, then this would result in more RGDP, but people would be worse off because they sacrified the leisure. (Assuming they were free to work 6 days a week if they wanted.)

But your problem is that is bunch of Austrian economics confusion. In particular, a confusion of “goods of the lower order” with “final goods and services.” They sound similar, but the Austrian goods of the lower order are consumer goods, while final goods include capital goods, inventories of materials, and partiall finished goods. In Austrian lingo, those are all goods of a higher order.

29. April 2013 at 06:59

Off topic- everyone check out Greg Mankiw’s blog right now. You won’t regret it.

29. April 2013 at 07:19

Laurent — probably most of us would agree the BoE has been better than the Fed, and much better than the ECB.

I can’t figure out if the ECB is running on memories of Weimar, or if they just like punishing the less productive, more spendthrift countries.

29. April 2013 at 07:53

[…] In fact, RGDP can be affected by either demand or supply shocks. If one uses RGDP changes as evidence of demand shocks, then the Keynesian model becomes close to tautological. RGDP weakness must be caused by demand-side problems, because poor RGDP data is defined as a demand-side problem! Thus you have the absurdity of people like Noah Smith proclaiming Paul Krugman as some sort of superhero, because he predicted that fiscal austerity would reduce AD in Britain. When British RGDP does poorly this is trumpeted as “proof” that the Keynesian model is correct, even though supply-side problems explain at least 75% of the RGDP slump, and perhaps even more. […]

29. April 2013 at 08:50

Geoff, Your comment on Balls is laughable. Do you even know who he is? Do you know that he favors more demand-side stimulus?

29. April 2013 at 09:48

“To summarize, if we make the most Keynesian assumption that is plausible, a low natural rate of unemployment which has not been rising, and if we assume that 100% of unemployment is due to a demand shortfall, and if we assume that unemployed workers are just as productive as employed workers (no ZMPers), then it still appears that the recent British stagnation is 75% to 80% supply-side and 20% to 25% demand-side.”

Can you please explain how you’ve done this calculation? These number are very close to what you would get if you just took the difference between the actual unemployment rate and the natural rate, and then divided by the actual — which is what I certainly hope you’re not doing.

29. April 2013 at 09:53

Scott, could you explain how you arrived at 4-5% in the following line?

“Then the current unemployment rate is probably 2.0% to 2.5% above the natural rate, which suggests that high unemployment has depressed output by 4% to 5%.”

29. April 2013 at 10:33

I’ll take Travis’ question one step further and ask how you took the 4-5% figures and concluded that 20-25% of the shortfall is demand-side?

29. April 2013 at 10:44

Bill Woolsey:

“You are confusing real GDP with the production of consumer goods.”

No, I’m not confusing those at all. Civilian goods includes both consumer and capital goods, devoted to civilian consumer preferences. I am saying that if the choice is between higher RGDP now and more military weapons, versus lower RGDP now and fewer military weapons, MM/Keynesian theory holds the former as more optimal, since RGDP is higher now.

Maybe you’re looking to find some confusion so bad you’re making confusions up?

“A country that produced fewer military goods now, and instead produced capital goods, including partially finished goods, stockpiles of materials or anything else that would help produce consumer goods later would have the same real GDP.”

It most certainly would not. Producing more capital goods now instead of military goods or consumer goods now, will bring about the production of both more consumer goods and more capital goods later on. With less capital, and more military goods instead, workers will have fewer and lower quality capital goods to work with going forward, and that reduces real GDP, it doesn’t leave it unchanged.

“It is probably the case that RGDP fails to property account for depletion of nonrenewable resources, but that is about it.”

A very significant failure, and you’re essentially conceding my point. But that isn’t the main point I’m making.

Resources, all resources, are scarce. You can only do one thing with a capital resource at a time. The more resources are devoted to uses other than capital accumulation, the lower will the productivity become, ceteris paribus, in the future.

“An obvious failue of RGDP is that if people decided that they would be happier working only 4 days a week, and spent the extra day in fun recreation, which they value more than the present and future consumer goods and services they give up, then RGDP would fall, (alot) but happiness would rise because of all the vaulable free time.”

Opportunity for leisure is increased through higher productivity of labor, which is itself based on capital invested per worker. The more productive the average worker becomes, the less he has to work to secure a sufficient real income, and the more time off he can enjoy.

“Conversely, if the government mandated everyone work 6 days a wekk, then this would result in more RGDP, but people would be worse off because they sacrified the leisure. (Assuming they were free to work 6 days a week if they wanted.)”

Not necessarily. People can arrive at at their place of work, but produce comparatively little, as little as what would be required to replace that which is used up through accommodating employees and managers at a business. The government cannot literally force labor without turning into slave masters.

“But your problem is that is bunch of Austrian economics confusion.”

Ah yes, the tried tested and true baseless accusation. I am not an Austrian, BTW.

“In particular, a confusion of “goods of the lower order” with “final goods and services.” They sound similar, but the Austrian goods of the lower order are consumer goods, while final goods include capital goods, inventories of materials, and partiall finished goods. In Austrian lingo, those are all goods of a higher order.”

This is just semantic quibbling. You aren’t revealing a confusion in Austrian theory by saying that you define final goods as those that include capital goods, inventories of materials, and partially finished goods. And you certainly didn’t reveal any confusion from me because you didn’t even grasp what I argued, and you instead went off on some ridiculous straw man tangent.

Here’s some advice: Go back and actually read what I wrote, and (hopefully) you’ll get it this time.

—————

Dr. Sumner:

Yes I know who Balls is and yes I know he favors “stimulus.” My statements regarding the notion that him not wanting to change the BoE’s 2% price inflation to be a “disgrace”, is not me arguing that he wants less monetary stimulus. It is me arguing that because price inflation affects (many) people’s standard of living (in the negative direction), it would be shameful to pretend that price inflation is irrelevant or does not exist, because of some allegedly more superior target of NGDP.

Individual people don’t get paid in NGDP. They don’t buy all the goods sold that make up NGDP. Individual people are paid in terms of prices and they pay other people in terms of prices. If the prices they have to pay go up, faster than the prices of the goods and services they sell, such that it reduces their standard of living, then I would consider it a “disgrace” for politicians to pretend that price inflation doesn’t matter.

Yes yes, I know the MM belief that we’re supposed to choose between having jobs and paying higher prices, or not having jobs and paying lower prices, and so only a fool would choose the latter, so it really isn’t prices at all. But not everyone is faced with that choice, and more inflation now will make many people have to choose between touch choices like sending their children to college or paying for their medicine. Not everyone is faced with more inflation or unemployment. In the UK, a small minority, even by MM standards, is in that position. Why should so many others pay higher prices for the sake of the CB achieving a new target?

INB4 “you’re not being pragmatic.”

29. April 2013 at 12:27

Geoff: The problem is, that you’ve presented no evidence that a higher inflation target would result in a worse outcome for the average person, on net. You always bring up your standard hypotheticals: _if_ a person’s prices rose, but their income didn’t, _then_ they would be worse off.

But you’ve been trolling on this blog for months and months now. Obviously you already know that people here don’t believe your hypothetical is at all likely, and instead strongly believe that a higher inflation target would be, on net, a strong positive for the average citizen.

If you want to contribute productively to the conversation, you need to provide some evidence that your concern of rising prices without rising wages is likely (as opposed to just possible). On the other hand, if your goal is merely to be annoying, keep posting your standard rant, which never changes and is so easy to just dismiss.

29. April 2013 at 12:45

Is Geoff really just Major Freedom re-spawned?

29. April 2013 at 12:46

Don Geddis:

“Geoff: The problem is, that you’ve presented no evidence that a higher inflation target would result in a worse outcome for the average person, on net.”

The average person does not exist.

I am talking about specific people. Specific individual people who through no fault of their own, just so happened to be in the path of monetary flow that sees the prices they pay for goods rise faster than their own incomes.

You want evidence for this? Just consider any individual who doesn’t get 2% or 3% (annualized) income raises every single month. Are you telling me that they don’t exist?

“You always bring up your standard hypotheticals: _if_ a person’s prices rose, but their income didn’t, _then_ they would be worse off.”

You always deny it.

“But you’ve been trolling on this blog for months and months now.”

You obviously do not understand what a troll is. Hint: It’s not someone who adheres to a different economic worldview than you, and it is certainly not someone who does not fail to take into account the costs of inflation that trolls like you always overlook or minimize.

“Obviously you already know that people here don’t believe your hypothetical is at all likely, and instead strongly believe that a higher inflation target would be, on net, a strong positive for the average citizen.”

The average citizen does not exist. See this is your problem. You’re reifying non-existent abstract concepts. By your warped logic, if there was a two person society, and one person gained 50%, while the other lost 25%, you would conclude that “the average person gained”, despite the fact that there is a person there who lost.

I don’t care that you merely disagree with me. I don’t operate like you do, where I only say things that the local group of people would want to hear. I am not a follower like you. You want blind obedience and acceptance.

“If you want to contribute productively to the conversation, you need to provide some evidence that your concern of rising prices without rising wages is likely (as opposed to just possible).”

You need to show evidence that monetary inflation makes every single person’s income rise at no less than the rate of the prices of the goods they buy.

What’s that? You don’t have that evidence? Then I won’t take you seriously.

“On the other hand, if your goal is merely to be annoying, keep posting your standard rant, which never changes and is so easy to just dismiss.”

You only find me annoying because you don’t like having your worldview exposed as flawed. That’s all this is.

Try harder. Every single time you respond to me, it’s always the same. We don’t accept your assumptions. We don’t accept your assumptions. We don’t accept your assumptions.

You say this constantly like I would ever dream of questioning myself on the basis of mere disagreement.

You’re going to have to do a lot better than sticking your fingers in your ears. If I “annoy” you, then too bad for you. Man up bro, and quit bit@hing.

29. April 2013 at 12:46

Geoff,

Note that the point about Ed Balls is that he favors more demand-side stimulus. If you get more demand, does not matter where it comes from, you will get higher inflation. The only way demand-side stimulus could possibly work would make inflation higher.

So the thing is, he wants more demand, but wants inflation to keep low. And that is impossible. He can get low inflation, or he can get more demand, but cannot get both.

That’s why it’s funny you see?

The best (worse) thing he could get is a big gov. fiscal expansion with a monetary offset.

29. April 2013 at 13:37

Arthur:

Yup, that point is valid.

29. April 2013 at 15:45

Major Geoff Freedom – you say

“You need to show evidence that monetary inflation makes every single person’s income rise at no less than the rate of the prices of the goods they buy.”

Why should the standard for any policy be that high? Most governments have a policy to arrest, imprison and some even execute murderers. Obviously, that doesn’t benefit every single person. (Those who want to murder people, people who love or depend on them, taxpayers who pay the costs but wouldn’t have been murdered without the laws.) We do a cost/benefit analysis and decide it is better for most people to outlaw and punish murder.

And furthermore, if inflation is zero, not every single person’s income will keep up with the rate of prices. Some people will see a nominal drop in income while prices stay the same. So we need to do a cost/benefit analysis to determine the best monetary policy. Hyperinflation, Deflationary Depression, or stable money in terms of GDP (market monetarism).

29. April 2013 at 16:26

Negation of Ideology:

“Why should the standard for any policy be that high?”

Who said anything about standards?

Speaking of standards though, why should innocent people be made to suffer, for the benefit of others? From where does that dogma originate? Utilitarianism? The same dogma that would sanction slavery, or murder, or any other unspeakable horror, if it just so happens to make the greatest number of people in an arbitrary population happier?

“Most governments have a policy to arrest, imprison and some even execute murderers. Obviously, that doesn’t benefit every single person.”

That’s different. I’m talking about innocent people, not people who murder others.

“We do a cost/benefit analysis and decide it is better for most people to outlaw and punish murder.”

This is a figment of your imagination. There is no such thing as social costs or social benefits. There is no such thing as social benefits arising because there are people who gained more in material terms as compared to people who lost in material terms. There is always losses to some and gains to others.

The only real world cost and benefit are subjectively grounded costs and benefits at the individual level. Everything else is nothing but apologia to harm others for one’s own benefit.

“And furthermore, if inflation is zero, not every single person’s income will keep up with the rate of prices.”

But that wouldn’t be because of the arbitrary nature of inflation. My argument is about the income effects of inflation.

You might as well say that if murder were zero, not everyone would die at the same age, so what’s the big deal with murder shortening some people’s lives.

“Some people will see a nominal drop in income while prices stay the same. So we need to do a cost/benefit analysis to determine the best monetary policy.”

Again with the figment of your imagination.

“Hyperinflation, Deflationary Depression, or stable money in terms of GDP (market monetarism).”

Talk about false dichotomies.

It is not necessary to choose between those three loaded alternatives. You might as well say the only alternative is hyperinflation, deflationary depression, or free market in money.

29. April 2013 at 16:58

Major Geoff: “You want blind obedience and acceptance.”

Not at all. I welcome constructive disagreement. I just want someone who thinks before he speaks, and isn’t just a tape recorder.

Allow me to quote Winston Churchill: “A fanatic is someone who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject.“

29. April 2013 at 17:34

JSeydl, Travis and Jeff.

If unemployment is 2% to 2.5% too high, then Okun’s law says output is depressed by 4% to 5%. But the productivity slump depressed output by another 15% relative to trend. In total, output is depressed about 19% to 20%.

So the demand share of the gap is roughly 4/19 or 5/20, i.e. about 20% to 25% of the gap.

Geoff, If you know about Ed Balls, then your comment is nonsensical.

30. April 2013 at 10:07

ssumner,

It looks like a neat little calculation, but your contribution to the slump from productivity may be too high. I really think the analysis needs to be done across cycles. A slowdown in productivity growth always depresses output at this stage in recovery. The question is, how much more than usual has it depressed output this time relative to past recoveries?

I might play around with this if I have some time.

30. April 2013 at 11:06

JSeydl, You lost me somewhere. Doesn’t the Okun’s law estimate already take into account the impact on the business cycle on productivity?

However I may have erred, as it probably should be 4/17 or 5/18. Productivity plus employment shock gives you total decline in output.

30. April 2013 at 13:06

ssumner,

I have no problem with using Okun’s Law in the way you have. My question is about what you’re doing on the productivity side. What are you using for trend productivity growth? If I look at the labor productivity data from the OECD, it looks like UK productivity increased by 1.6% in 2010, then slowed to 0.4% in 2011, and then turned negative to -1.1% in 2012. I don’t think you’re doing this, but one could say that relative to what would be the case if productivity had kept growing at a 1.6% annual pace, the current slump in productivity is depressing output by whatever percent. But you’d be inflating the problem if you did the analysis this way because, again, we expected productivity growth to slow.

One approach could be to look at how productivity behaved in the previous recovery, then index that trajectory to the current cycle, and then use the difference as an estimate of how much of the slump in productivity is not “normal.” Of course, going further back and using an average of the last several recoveries would be even better.

30. April 2013 at 21:01

[…] Source […]

1. May 2013 at 03:00

Is it now also the case the the UK gov and BoE are protecting/boosting house prices and rents like no other nation? The number of schemes and support measures in place seem to grow by the month – with the latest being state backed cheap lending to buy-to-let investors and the wreckless Help to Buy scheme.

Here’s a little summary…

http://www.mindfulmoney.co.uk/wp/shaun-richards/will-uk-economic-policy-ever-stop-subsidising-our-banks-and-housing-market/

1. May 2013 at 14:20

JSeydl, I’m using Wren-Lewis’s estimates. I’m saying that if he’s right about productivity, then the slump is at least 75% supply-side, and perhaps much more. Obviously he may be wrong.

22. August 2013 at 00:58

[…] economy has performed notably poorly: rather worse than the demand-side problems suggest. This implies supply-side problems; such problems are classically the result of problematic public […]

6. October 2013 at 12:47

[…] The output shortfall is at least 75% productivity, and at most 25% […]