Rising NGDP in Japan equals jobs, jobs, and more jobs

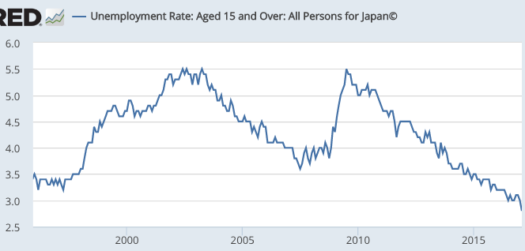

The labor market data out of Japan is nothing short of spectacular. The most recent data shows the rate falling to 2.8%, the lowest rate in decades:

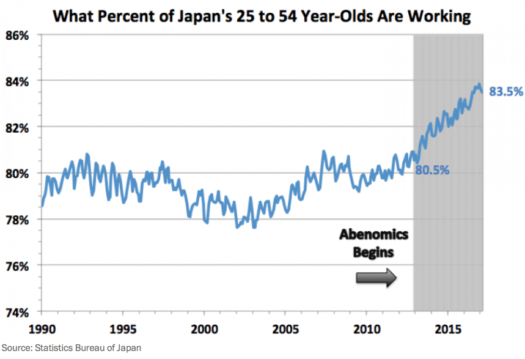

And that’s not just due to people abandoning the labor force, as has been claimed regarding US data. In start contrast to the US, the employment to population ratio is soaring to new highs. This is from a Matt O’Brien article in the WaPo:

And that’s not just due to people abandoning the labor force, as has been claimed regarding US data. In start contrast to the US, the employment to population ratio is soaring to new highs. This is from a Matt O’Brien article in the WaPo:

Anecdotal evidence also suggests an ultra-tight labor market:

Every shop and restaurant in Tokyo seems to have a “positions vacant” sign, and many are scrapping 24-hour opening to save labour. Yamato Transport, the country’s largest logistics company, is raising prices for the first time in 27 years in a deliberate attempt to cut volumes to a level its network can handle. Rather than cutting costs, chief executives spend their time working out how to hire and retain staff.

After more than two decades when labour was cheap and abundant, Japanese companies are finding ways to cut back, reducing their lavish service standards rather than raising prices. But this can only go so far. Japan is primed for inflation.

The struggles of the stimulus must also be weighed against the global economic backdrop. The plunge in 2014 in commodity prices, followed by the 2015 slowdown in emerging markets, leading to a sharp appreciation of the yen, were a terrible environment in which to generate inflation. Only with the election of Donald Trump as US president, and the subsequent rally in the yen above ¥110 to the dollar, is the global economy once again a support.

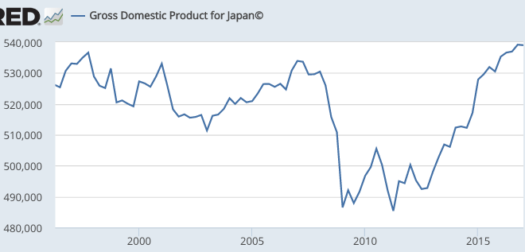

That’s right, this success occurred against a backdrop of substantial headwinds. How did they do it? After he took office at the beginning of 2013, Abe set a goal of raising NGDP from 492 trillion to 600 trillion yen. The inflation target was raised to 2%, and Kuroda was appointed to lead the BOJ. NGDP started rising almost immediately, breaking out of a two-decade period of sluggishness.

Japan is now almost half way to its NGDP target.

Japan is now almost half way to its NGDP target.

To be sure, there are weaknesses. Inflation has averaged less than the 2% target, and is expected to continue doing so. There was no date given for the 600 trillion yen NGDP target. But overall, Abenomics has been a big success.

It’s also boosting RGDP. Here’s the Financial Times:

Japan has recorded its longest run of sustained growth in more than a decade as stimulative policy and a healthier global economy lead to a period of robust progress.

Growth for the first quarter of 2017 came in at an annualised 2.2 per cent, according to the Cabinet Office, marking five quarters of continuous expansion in gross domestic product.

The figure beat the consensus analyst forecast of 1.7 per cent and is far above Japan’s long-run growth potential of roughly 0.7 per cent. That suggests the economy is using up spare capacity and unemployment will keep on falling.

The lesson here is that when you have a labor market that is facing inadequate AD, the solution is simple—more NGDP. But printing money can’t perform miracles. Relatively soon Japan will reach capacity, and RGDP growth will stop. At that point the BOJ must keep NGDP growing at 2% per year to ease its public debt burden.

And all of this occurred against a backdrop of zero interest rates and fiscal austerity—something Keynesians insist is impossible. I can’t emphasize enough that Keynesian economics has negative value added, it simply doesn’t help us to understand what’s going on around the world.

Tags:

18. May 2017 at 06:47

I largely agree with the points made in this post.

Japan commentators seem to be concerned about the road forward. They believe that the BoJ cannot buy much more Japanese government debt without causing problems for institutional investors such as insurance companies. In some sense, this is comical, as it would indicate that the Japanese government debt is too small! They also believe that the BoJ cannot buy much more Japanese equities, as a larger position would be a risk both for the BoJ and the market.

That said, I fail to see why the BoJ can’t simply go and buy other Japanese assets, such as mortgages (stealing a page from the Fed’s playbook) or corporate debt. It could also imitate the SNB and buy foreign assets. Notwithstanding it could further lower its negative interests on reserves.

18. May 2017 at 07:10

Yes…. except the Yamato anecdote has nothing to do with economics. It’s simply a function of the explosion of Amazon’s business in Japan.

18. May 2017 at 07:27

But, but, but Krugman the Great says differently in his columns.

18. May 2017 at 08:49

Aside from the obvious benefits of a trading partner growing strong, we might be the beneficiary of such tight labor conditions if it leads Japanese companies to invest more in automation technologies (boosting productivity).

18. May 2017 at 09:38

“At that point the BOJ must keep NGDP growing at 2% per year to ease its public debt burden.”

Typo?

Wouldn’t the bank of Japan want higher NGDP than that? With a 2% inflation target, wouldn’t they want 4% or 5% NGDP to ease the debt burden?

18. May 2017 at 12:47

Isn’t this as much about demographics? Japan’s population is famously falling and aging. There’s simply not enough people to do the jobs. This may have something to do with NGDP and inflation, but that seems the simplest explanation.

18. May 2017 at 15:06

LK, I agree.

dtoh, Thanks for that info.

XVO, I am assuming a trend RGDP growth rate of 0%, and a 2% inflation target. I don’t have a big problem with a 4% NGDP growth target for Japan, but I doubt they want that much inflation. With a 2% NGDP target, wages should rise about 3% a year, assuming the labor force contracts by 1%/year.

msgkings, Keynesians like Krugman say a falling population is contractionary.

18. May 2017 at 16:18

“The lesson here is that when you have a labor market that is facing inadequate AD, the solution is simple—more NGDP.”

You don’t know the economic meaning of “inadequate” without a free market in money production.

You only have a socialist meaning.

If someone believed to know that aggregate oil production, or potato production, or car production, or penicillin production, was “inadequate”, that it should rise at X% per year by the force of state, then a reasonable person who respected enlightened western values would rightfully reject that as wrongheaded and destructive.

Yet here you are pretending to know what the right production in a commodity, money, ought to be.

18. May 2017 at 16:45

Great post… But Scott. you daintily step around the positive role of the Bank of Japan’s QE program.

Recently, you said “helicopter drops don’t work” in Japan.

Make up your mind!

18. May 2017 at 17:37

“I can’t emphasize enough that Keynesian economics has negative value added, it simple doesn’t help us to understand what’s going on around the world.”

Neither does anti-market monetarism, which is just a “Counterfeiters instead of the Treasury” form of Keynesianism.

Monetarism has negative value the same way Keynesianism has negative value, and also doesn’t help anyone understand what’s going on in the world.

The Keynesians were convinced their theory enabled them to understand the world, and they still are so convinced. Monetarists and Keynesians are under the same illusion.

Monetarism falsely starts with aggregate demand as the foundation, instead of individual human action. No individual acts on the basis of aggregate anything. It is a mythology.

The monetarist method is just one of the many ways that denial of methodological individualism can occur. Someone who worried all day over the aggregate number of potatoes exchanged would be just as enlightened.

Aggregate demand does not cause employment, nor does it cause investment in capital, nor does it cause any other phenomena that is logically and temporally antecedent to it. Not even “expected” aggregate demand does so. The false move is to commit the fallacy of composition; to say that “just like” an individual producer invests because he expects a future individual profit, “so too” does the economy as a whole operate that way.

NOOOOOOPE.

At the level of the economy as a whole, the individual expenditures offset, and the relationship between investment and consumption is the other way around. At this level, which is still individualist, but coincidental individualist activity, not only does consumption depend entirely on investment, both in real terms AND nominal terms, but consumption spending is actually in competition with investment spending.

But this dependency is not consciously directed by any singular individual, and THAT’S what makes the socialist mind explode, and the shaking of the head and no no no’s, and the knee jerk rejections take hold, because to the socialist mind, there is the ever pervasive single consciousness “MIND” that directs everything. If humans don’t pay attention to it, and if they don’t OBEY IT, then society is doomed. See that? There MUST be an intelligence, a singular consciousness, to represent and guide the “aggregated” individual phenomena.

This is the root of the problem for Monetarists and Keynesians. Their philosophical underpinnings derive from a mythological Hegelian conception of reality, just like the Marxists. They don’t understand the phenomena of unguided, uncontrolled – what Hayek unfortunately and unintentionally misleadingly called – “spontaneous order”. It is the phenomena that occurs as a result of billions of separate, individual actions, like billions of billiard balls on an infinitely expansive flat planar surface. That too is misleading, but less so than the reified summations and additions that are perceived as having mythological/supernatural powers.

Aggregate nominal demand logically and temporally FOLLOWS nominal investment in labor, it FOLLOWS nominal investment in capital. Indeed, aggregate demand is FINANCED by nominal investment in labor and capital. The people spending money on output, have already earned money through inputs, and that earning of money through inputs is investment. The counterfeiters are not printing and spending money on final output goods and services, they are printing money into money lender coffers. Their lending more than what people have sacrificed through saved earnings, distorts interest rates and credit, and that causes the business cycle.

Crucially, and as mentioned, aggregate nominal demand for output is in fact IN COMPETITION with nominal demand for everything else not nominal demand for output. One cannot spend the same dollar on two different things at the same time. The higher the aggregate nominal demand for output, the lower the demand for labor and for capital, ceteris paribus.

The monetarist worldview is backwards. It perceives a particular outcome, and believes the outcome drives that which is actually needed to drive that very same outcome.

If we see nominal aggregate demand going up, and employment going up, and production going up, it is not because the aggregate demand went up, nor is it correct to say that because aggregate demand went up at least it didn’t have a negative effect on employment and investment in capital.

The crisis of 2008-2009 was preceded by a crisis in investment.

Individual people do not even act as if they expect some particular aggregate demand to be this or that. Sumner hasn’t spent the last year publicising his Trump derangement syndrome because he expected today’s NGDP to be what it is as opposed to something else. No individual takes specific action today on the basis of expected aggregate demand tomorrow. Nobody. Anyone who claims to, is either lying or is misguided.

18. May 2017 at 19:55

@ssumner: I know Keynesians say that, I’m wondering if they are wrong about that along with all the other stuff. Could the tight labor market in Japan be about demographics instead of NGDP? Or are they perhaps the same thing, each aspects of the same situation?

19. May 2017 at 00:26

A typo: last sentence should be ‘simply’ not ‘simple’.

Excellent post otherwise.

19. May 2017 at 01:47

From Nikkei Asian Review today:

“A record-high 97.6 percent of new university graduates in Japan have landed jobs as of the April 1 start of the 2017 business year, government data showed Friday, reflecting demand from companies amid the nation’s labor shortage.

The rate increased 0.3 percentage point from a year earlier, up for the sixth consecutive year, in an annual survey conducted since 1997 by the labor and education ministries.”

—30—

And Tokyo is now rated as the most livable big city in the world for its affordable housing, healthy job scene and good public transit. And civilized people—you likely do not get mugged.

Good luck in America.

On average, your children will make less than you do and live in crappy cities.

19. May 2017 at 15:43

Scott writes:

“Relatively soon Japan will reach capacity, and RGDP growth will stop. At that point the BOJ must keep NGDP growing at 2% per year to ease its public debt burden.”

Does that hold true so long as they continue to run a trade surplus?

19. May 2017 at 21:52

I do wonder if “fiscal austerity” defines Japan.

“And all of this occurred against a backdrop of zero interest rates and fiscal austerity—something Keynesians insist is impossible.–Scott Sumner

But from Japan Times:

“Based on that scenario, the government expects to issue ¥34.37 trillion in new bonds in the next fiscal year, down 0.2 percent from the initial fiscal 2016 budget. It will still rely on debt to pay for 35.3 percent of its expenditures.”

So Japan is borrowing about one-third of the money to run its national budget.

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2016/12/27/editorials/fiscal-2017-budget/#.WR_YPks8PHg

Of course, Japan also has the Bank of Japan conduct QE, at about 80 trillion yen a month or $700 billion a year.

This post is like a jigsaw puzzle with pieces missing…

20. May 2017 at 05:47

Ben, The helicopter drop occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s—it did not work. Fiscal policy has tightened.

Your other comments don’t relate to this post.

msgkings, Krugman says a falling population is contractionary.

Lorenzo, Thanks, I fixed it.

Matthew, Yes.

22. May 2017 at 04:41

a post on Japan

http://ngdp-advisers.com/2017/05/22/abenomics-is-working/

28. May 2017 at 03:14

Why 2% ? This target is too low, isn’t it?

> the BOJ must keep NGDP growing at 2% per year to ease its public debt burden.