Reply to Williamson on NGDP targeting

Steve Williamson has a new post on NGDP targeting that gets off to a bad start:

Nominal GDP (NGDP) targeting as a monetary policy rule was first proposed in the 1980s, the most prominent proponent being Bennett McCallum.

A number of interwar economists, including Hayek, advocated NGDP targeting. (Actually nominal income targeting, as the term ‘NGDP’ was not yet widely used.) People should read George Selgin’s work on the history of NGDP targeting.

Then things get much better, as Williamson has an excellent discussion of the evolution of the NGDP. And then I start to have some problems with his analysis:

One might imagine that Sumner would have the Fed conform to its existing operating procedure and move the fed funds rate target – Taylor rule fashion – in response to current information on where NGDP is relative to its target. Not so. Sumner’s recommendation is that we create a market in claims contingent on future NGDP – a NGDP futures market – and that the Fed then conduct open market operations to achieve a target for the price of one of these claims.

Imagine buying a boat and being told by the sales person that the steering works fine 99% of the time, and only fails in wild and raging typhoons. I don’t know about you, but a stormy day is when I most want the steering mechanism to work. And it’s during periods where NGDP falls far below trend (1932 and 2009) where I most want my monetary policy instrument to work. Given rates are at zero, and we need more stimulus, it seems an odd time to question my dissent from interest rate targeting orthodoxy.

More importantly, I rarely discuss NGDP futures targeting in my blog, as I know it’s not going to happen anytime soon. I certainly have plenty of advice on other techniques the Fed could use. But later in the post Williamson makes this questionable claim:

The only policy instrument that currently matters is the interest rate on reserves (IROR).

I can think of several other options. For instance, the Fed could do lots more QE. The purpose of QE is to raise inflation and/or NGDP growth expectations. I’m sure there are lots of models where QE doesn’t work, but in the real world is does work. Fed policy statements hinting at QE had an obvious and unmistakable effect on asset prices in late 2010, including TIPS spreads. Now you might argue that market participants were foolish to believe in QE (as Krugman once seemed to imply.) But even Krugman eventually conceded that higher inflation expectations are higher inflation expectations, and it doesn’t much matter whether they occur for the right or wrong reason. In fairness, even I have some doubts about whether QE is the best way to go. It’s a clumsy tool. And although (I believe) I was the first to publish a paper advocating negative IOR, I also have doubts about whether that’s the appropriate policy. Instead, I think by far the best option is to set a NGDP target, and more importantly, to engage in level targeting. This sort of policy announcement would immediately boost NGDP growth expectations (or reduce real interest rates if you prefer to model things that way.) If the Fed had done that back in early 2008 we never would have hit the zero bound in the first place, as expected NGDP growth would have been far higher, and nominal interest rates are strongly impacted by changes in expected NGDP growth (but also deviations from trend.) That’s why countries like Australia don’t have to worry about the zero rate trap, they keep NGDP growing fast enough to avoid it.

Williamson continues:

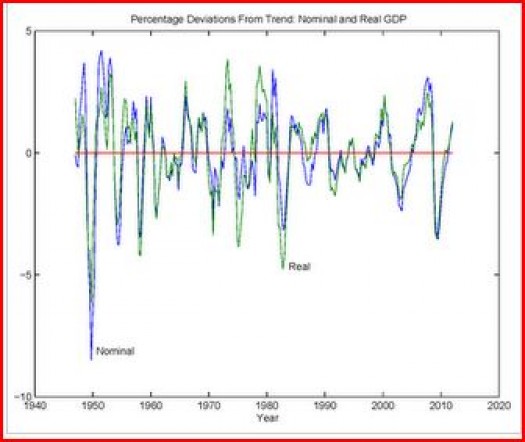

So, what do we make of this? If achieving a NGDP target is a good thing, then variability about trend in NGDP must be bad. So how have we been doing? The first chart shows HP-filtered nominal and real GDP for the US. You’re looking at percentage deviations from trend in the two time series. The variability of NGDP about trend has been substantial in the post-1947 period – basically on the order of variability about trend in real GDP. You’ll note that the two HP-filtered time series in the chart follow each other closely. If we were to judge past monetary policy performance by variability in NGDP, that performance would appear to be poor. What’s that tell you? It will be a cold day in hell when the Fed adopts NGDP targeting. Just as the Fed likes the Taylor rule, as it confirms the Fed’s belief in the wisdom of its own actions, the Fed will not buy into a policy rule that makes its previous actions look stupid.

That makes no sense to me. During the 1980s and 1990s the Fed moved toward a rule (call it the Taylor Rule, inflation targeting, whatever) that made their previous high inflation policy of the 1970s look stupid. In fact if you speak to Fed officials they love to tell you how misguided Fed policy was during the Great Inflation, and how they’ve done a much better job since about 1983.

Williamson continues:

There’s another interesting feature of the first chart. Note that, during the 1970s, variability in NGDP about trend was considerably smaller than for real GDP. But after the 1981-82 recession and before the 2008-09 recession, detrended NGDP hugs detrended real GDP closely. But the first period is typically judged to be a period of bad monetary policy and the latter a period of good monetary policy.

I have several problems with this. It’s been a long time since I studied detrending, but I recall McCallum pointing out during the great “unit root” debate that it’s very difficult to detrend GDP. Look at how NGDP falls from about 3% above trend in 2008 to 3% below trend in 2009, a swing of 6% relative to trend. We know that NGDP fell 4% in absolute terms between 2008:2 and 2009:2, which I assumed was at least 9% below trend. His graph seems to imply that trend NGDP during that 12 month period was 2% at most (6% – 4%.) Correct me if I’m wrong, but could the HP filter approach be distorted if the dramatic collapse in NGDP after 2008 was allowed to impact estimates of trend? And I’d completely reject that claim that NGDP was as far above trend in 2008 as it was below in 2009.

But even if I’m wrong on this technical question, I don’t think he’s drawing the right conclusions. The 1970s were bad for a number of reasons. One was the unusually large supply shocks, such as the oil embargo and the off and on wage/price controls. These made output more unstable, and lower, that what would have been implied by NGDP shocks alone. And the Fed had no control over those factors. Another huge problem was the rapidly rising rate of inflation, and also inflation expectations. Evan Soltas has a new post pointing out that this dramatically raised the real tax rate on capital, and hence the stock and bond markets did very poorly. That was what most people are talking about when they blame the Fed for bad monetary policy. There was also some instability of NGDP growth, but Steve’s right that it was not far out of the ordinary. But even here I’d be careful with the data. In the early 1980s we had some severe RGDP and NGDP instability, which was due to Fed policies aimed at squeezing inflation out of the economy. This could be regarded as a legacy of the bad policies of the 1970s. Since about 1984 there has been some reduction in NGDP instability, until 2008 or course. Marcus Nunes has looked at the data much more closely than me, and can document this fact.

Update: Here’s Marcus, with graphs that conform much more closely to what I recall happening. Ditto for this graph sent by commenter Brano.

Williamson continues:

So, if variability about trend in NGDP is a bad thing, why should we not worry about the seasonal variability? I can’t see how any answer that the NGDP targeters would give us to that question could make any sense. But they should have a shot at it.

I think this shows just how far apart we are in terms of thinking about the problem of business cycles. I may be wrong in the answer I’m about to give, but quite frankly I’m surprised that Williamson didn’t anticipate it, indeed wonders whether there is an answer. Most mainstream economists, both Keynesian and monetarist, distinguish between optimal output fluctuations, roughly those that would occur if all wages and prices were completely flexible, and suboptimal output fluctuations, which are presumably generated by the interaction of demand shocks and wage/price stickiness. (BTW, I know the term ‘demand’ is not clearly defined, I just mean NGDP shocks.) Most economists assume that season output fluctuations (in industries like construction, retailing, agriculture, etc) are efficient. The fluctuations in hours worked in those industries that are due to seasonal factors are predictable, and do not cause huge welfare losses. In contrast, RGDP fluctuations at cyclical frequencies are assumed to be suboptimal, and are assumed to generate large welfare losses—particularly when generated by huge NGDP shocks, as in the early 1930s. That may be wrong, and obviously one would need a lot of labor market modeling to formalize this conjecture, but I’m pretty sure it’s the assumption that 90% of mainstream economists have in the back of their minds. But now I’ll give Williamson “a shot” at my conjecture.

Williamson continues:

The monetary models we have to work with tell us principally that monetary policy is about managing price distortions. For example, a ubiquitous implication of monetary models is that a Friedman rule is optimal. The Friedman rule (that’s not the constant money growth rule – this comes from Friedman’s “Optimum Quantity of Money”) dictates that monetary policy be conducted so that the nominal interest rate is always zero. Of course we know that no central bank does that, and we have good reasons to think that there are other frictions in the economy which imply that we should depart from the Friedman rule. However, the lesson from the Friedman rule argument is that the nominal interest rate reflects a distortion and that, once we take account of other frictions, we should arrive at an optimal policy rule that will imply that the nominal interest rate should be smooth.

I certainly don’t agree with that, and I’m not sure Friedman would either. I had thought his argument was that a zero rate minimizes the opportunity cost of holding base money, which can be produced at zero cost. I thought he was critical of interest rate smoothing. But it’s been a long time since I read the article. In any case, once you add wage/price stickiness it’s not at all clear that stable interest rates are important. One could argue that the welfare cost of fluctuating short term risk free rates is trivial compared to the welfare costs of suboptimal employment fluctuations caused by sticky wages.

Williamson continues:

The idea that it is important to have the central bank target a NGDP futures price as part of the implementation of NGDP targeting seems both unnecessary and risky. Current central banking practice works well in the United States in part because the Fed (pre-financial crisis at least) is absorbing day-to-day, week-to-week, and month-to-month variation in financial market activity. Some of this variation is predictable – having to do with the day of the week, reserve requirement rules, or the month of the year. Some of it is unpredictable, resulting for example from shocks in the payments system. I think there are benefits to financial market participants in having a predictable overnight interest rate, though I don’t think anyone has written down a rigorous rationale for that view. Who knows what would happen in overnight markets if the Fed attempted to peg the price of NGDP futures rather than the overnight fed funds rate? I don’t have any idea, and neither does Scott Sumner. Sumner seems to think that such a procedure would add extra commitment to the policy regime. But the policy rule already implies commitment – the central bank is judged by how close it comes to the target path. What else should we want?

I have all sorts of problem here. First of all I’ve published two different papers discussing how the Fed could continue targeting the fed funds rate under a futures targeting regime, for periods of 6 weeks at a time if the Fed wishes. You set up a number of NGDP futures contracts auctions, each contingent on a different setting of the fed funds target. You announce that the contracts will only be exercised in the auction that, ex post, most nearly balances the long and short positions of NGDP futures speculators (which means the Fed takes little risk.) And then you set the fed funds rate at that level for the next 6 weeks. It’s not my favorite approach (remember the zero rate bound) but it’s doable.

Keep in mind we’ve operated for decades under other monetary regimes (such as the gold standard) which theoretically made the interest rate endogenous and hence uncontrollable. The question of whether to stabilize overnight rates for a few weeks at a time seems like a trivial footnote to me; there are much bigger issues to worry about. But yes, it can be done under NGDP futures targeting.

I have even more problem with the last part of the paragraph. If the Fed had an explicit target I wouldn’t be so single mindedly pursuing an NGDP target. Suppose they had a Charles Evans-type target minimizing the deviation of inflation from 2% and unemployment from 5.6%. In that case I’d criticize the Fed for falling absurdly short of their target, and then not lifting a finger to make up the difference. And I’d call for level targeting, to hold them accountable. Indeed while experts like Woodford (and Bernanke in pre-FedBorg days) correctly note that level targeting has all sorts of advantages at the zero rate bound, the biggest advantage is that central banks can’t go year after year saying “oops, we fell just short of our target, we’ll try harder next time.” Imagine if the BOJ had its 1% inflation target converted to price level targeting. There’d be panic—“Oh my God we are actually going to have to raise the price level! We can’t keep stringing them along with promises.”

Williamson concludes as follows:

Making promises about future NGDP cannot help the Fed do a better job of making promises about the future path for the IROR, so NGDP targeting appears to be of no use in our current predicament.

It can help because it’s hard to make credible promises about the future path of interest rates, unless they are conditional on various macro outcomes (inflation, NGDP, etc) otherwise the price level has no anchor. Presumably Williamson is assuming the Fed has a credible target, which I’ve already argued is not the case. Since we don’t have that, a higher NGDP target can generate monetary stimulus in a less risky way than a long open-ended promise of low rates.

I’m kind of perplexed as to why Williamson calls himself a “New Monetarist” (although perhaps it’s just my petty jealousy that he got to the term first.) It used to be that the sine qua non of being a monetarist was viewing monetary policy as being about changes in the quantity of money, not interest rates. Indeed when I was at the UC in the late 1970s anyone claiming that a fiat money central bank might be unable to create inflation by printing money (even at zero rates) would be laughed at. Now you have UC profs like John Cochrane basically teaching that view. Maybe I shouldn’t be such a reactionary; after all, some market monetarist ideas are also anathema to strict monetarists. Times change and macro theory never stops evolving. Still, I’d really like to know what stylized fact made all those US economists who were dismissive of the idea that the BOJ was out of ammunition in the late 1990s, suddenly come to the conclusion that the Fed is out of ammo. Is there some fact that disproved the previous conventional wisdom that I somehow overlooked? I suppose that’s unfair to Williamson, as at least he admits that IOR still works.

PS. Mark Thoma links to Williamson, and adds this comment:

I’ll be interested to hear the responses to his questions (assuming he has more luck than David Andolfatto in getting advocates of NGDP targeting to repond).

I’m surprised by this. I had a lengthy response, and I recall some other NGDP targeters did as well.

PPS. I still have some projects to finish, so I may not post much in the near future.

HT: Bill Woolsey.

Tags:

2. July 2012 at 19:34

If you really want to see a paper that makes your blood curdle, see this:

http://emlab.berkeley.edu/~ygorodni/CGKS_inequality.pdf

Is there anything worse than an interest rate hawkish progressive? Yes, I’m talking about you Simon Johnson.

“In recent decades, the Fed has given way completely, at the highest level and with disastrous consequences, when the bankers bring their influence to bear… As the American economy begins to improve, influential people in the financial sector will continue to talk about the need for a prolonged period of low interest rates. The Fed will listen. This time will not be different.”

-Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson

2. July 2012 at 19:49

Scott,

Well written and very informative post. Of course, I would add that there are many other things the Fed could do including: buying other types of assets, doing interest rates swaps, charging for exchanging into cash, converting from paper to electronic money (allowing them to set an expiration date or negative interest rates on cash), and most importantly setting minimum and maximum asset/equity ratios for banks.

2. July 2012 at 20:25

John C. Williams, President and CEO, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, speaks:

http://www.frbsf.org/news/speeches/2012/john-williams-0702.html

“It is through its effects on interest rates and other financial conditions that monetary policy affects the economy … what matters for the economy is the level of interest rates, which are affected by monetary policy.”

Not a particularly stirring speech, but if our host isn’t going to be posting much in the near future, it is something.

2. July 2012 at 20:49

Scott,

Speaking of disappointing critiques, how about former RBA Deputy Governor Stephen Grenville’s response to Ryan Avent’s fisking of the BIS report here: http://www.lowyinterpreter.org/post/2012/07/02/Blame-central-banks-Not-so-fast.aspx.

Key graf: “Perhaps the greatest problem with the critical commentary is the ignorance it demonstrates of how monetary policy actually works. The Economist, Wolf and Krugman all carry the legacy of Milton Friedman’s misleading message in which monetary policy works by increasing base money, expanded by the banking system through a credit multiplier. But extra base money doesn’t encourage banks to expand their lending; they are already lending to all the bankable customers who want to borrow at the going interest rate. The extra base money just accumulates in the banks’ balance sheets in the form of deposits with the central bank, with little or no effect.”

As an experienced central banker he no doubt has valuable insights to offer on transmission mechanisms, but it’s ridiculous to cast the Economist (and Ryan Avent in particular) as a carrier of ignorance when they’ve done so much to propagate market monetarist ideas which completely transcend the caricature of QE that Grenville describes.

2. July 2012 at 21:01

Is there anything worse than an interest rate hawkish progressive? Yes, I’m talking about you Simon Johnson.

And Acemoglu. He’s odd. He writes very persuasively about the great costs imposed by extractive monopolistic interest groups on societies today and all through history. But he’s so PC that that today here at home he denies that urban public schools teachers unions are any such thing and says monopoly govt employee unions should have more power generally as a matter of principle. As far as I can tell, his economic training and experience gives him as much knowledge of monetary policy and bank finance as a top matrimonial lawyer has of admiralty law. Yet I’ve seen him beating up on banks all over the place. No low interest rates if they would help banks!

The thing about extractive monopolistic institutions is they reap *high* returns for their stakeholders, as he very well documents, because … they have monopolistic powers.

Banks have been getting killed for years, the rate of return on bank equity has plunged with markets expecting it to stay low for the next decade. (“Bank returns on equity are too low to justify lenders’ existence” — The Economist. Acemoglu beats on them for being extractive. What are they extracting? I’ve never seen him square that.

2. July 2012 at 21:31

“Evan Soltas has a new post pointing out that this dramatically raised the real tax rate on capital, and hence the stock and bond markets did very poorly. That was what most people are talking about when they blame the Fed for bad monetary policy.”

Actually, “most people” just get scared when they see prices spiralling upwards at the grocery store.

I guess my interpretation of Williamson’s objection would be that he is wondering whether wages are flexible enough over short intervals to allow a curved-structure to the predetermined contract path, so that when NGDP is anticipated for the next 5 years we set nominal wages not only on a rising 5-year scale but also have the freedom to preset them with internal seasonal variability over the course of each year. Since an unexpected shock to the NGDP path takes more than a year to compensate for, perhaps wages aren’t flexible enough over short intervals even ex ante? But I don’t buy that.

With the Friedman rule, that sounds a lot like why Austrians are critical of what they see as central bank manipulation of the interest rate.

And finally, I really think it needs to get out more that Scott Sumner thinks level-targeting is more important than NGDP targeting. Journalists especially ought to be made aware of this.

Liberal Roman, the public would be much better off if it were made aware that economics is a broad discipline, and that brilliant scholars in one part (cough Stiglitz cough) really have no authority on things like stabilization policy. We should be wary of any economists coming forward with their own grand theories (inequality being the popular focus) linking all economic matters together.

2. July 2012 at 21:40

Jim Glass, Acemoglu is a great economist, but he seems to be committing the fundamental fallacy of non-economists – if rich guys are getting further rich off some policy, it must be evil/unfair.

Blair, what would Grenville say to the notion that IOR might have something to do with that “accumulation”? And even if he is ignorant of the excess cash balance mechanism, what would he say to a reductio ad absurdum? And the same goes for John C. Williams. Seriously, I don’t understand why every central banker in the world hasn’t read through this blog yet. No time? Make time.

More broadly, I think Keynesians are misled by the fact that spending plans are “tied down” by the interest rate. Yes; but the other thing they depend upon is nominal permanent income, and that is affected by the quantity of money in the long run.

2. July 2012 at 21:43

And that goes right to the heart of what’s wrong with Keynesian economics in general – myopic modelling, assumption of an irrational private sector, and reluctance to model budget constraints. New Keynesianism was supposed to fix that, but clearly it hasn’t – again as Mankiw says the formal models used by central bankers are still more Old than New Keynesian.

2. July 2012 at 21:47

And that’s reflected in the way they think about things and react to developments.

2. July 2012 at 23:11

Scott

Notwithstanding estimates of peaks and troughs around the trend, Williamson’s basic point with the graph remains. Don’t look just at the crash – he is syaing that in the great moderation, RGDP hugs NGDP. While in the 1970s, NGDP swings a lot lesser than RGDP. Even in absolute terms, the 70s seems to have as good a performance of stabilizing NGDP (between +2% and -2%) as the great moderation. So why is it that we seem to universally accept the great moderation as an era of successful monetary policy. Should we simply re-phrase that as saying that the great moderation was an era lucky for not having big supply shocks?

Also, minor, but seasonal variations in output of construction, agriculture etc. are not seen as efficient. But because they are regular and predictable, a well-functioning system of contingent credit and futures markets has developed to ensure that the cash flow and liquidity situations do not turn inefficient, even if output is not stabilized.

2. July 2012 at 23:13

Liberal Roman,

“If you really want to see a paper that makes your blood curdle, see this:”

I’m perplexed, as I like that paper. One of the principal reasons monetary stimulus is opposed by people on the left these days is that they see it as making inequality worse. Although the paper is interesting for what it has to say about the effect of monetary policy on earnings heterogeneity, its primary contribution is its analysis of the effect of monetary policy on financial income.

Thanks to that paper I discovered that it appears to be a regular empirical fact that aggregate financial (dividends, interest and rent) income tends to rise sharply while business income declines after contractionary monetary policy shocks. While the decline in business income is much larger, it is offset for high income households by the increase in financial income. Further, the top 1% of the income distribution receive approximately 30% of their income from financial income, a much larger share than any other segment of the population. This suggests that total income for the top 1% likely rises even more than for most households after contractionary shocks.

2. July 2012 at 23:19

Steve Williamson:

“There’s another interesting feature of the first chart. Note that, during the 1970s, variability in NGDP about trend was considerably smaller than for real GDP. But after the 1981-82 recession and before the 2008-09 recession, detrended NGDP hugs detrended real GDP closely. But the first period is typically judged to be a period of bad monetary policy and the latter a period of good monetary policy.”

I don’t know about Steve’s graph, but the fact is NGDP was more variable in the first period than the latter period (especially when compared to 1985-2005), which matches the general consensus as to which was a better period from the standpoint of monetary policy. The fact that RGDP was even more variable than NGDP during the period when NGDP was more variable only seems to imply that less variable NGDP is a good thing, right?

2. July 2012 at 23:24

Saturos

Apropos nominal permanent incomes being dependent on the quantity of money in the long run.

1. What is the long run?

2. Scott argues that in the long run, the price level depends on the quantity of money, not nominal income. What is your favoured version of the QTM? If the monetary regime has an unspecified quantity of money or nominal income policy, what expectations do people have of the permanent income?

3. What is your favoured definition of M anyway?

4. Multiple equilibria – What if the QTM is ‘right’, but no one believes that? Can the QTM hold if no one believes the QTM?

5. Endogeneity – Formulations of the QTM are not so much a causal mechanism as simply an equation. The causal mechanism depends on assuming all money to be ‘outside’, which is to assume the point. Many monetarists have recognized this issue – e.g. Patinkin.

6. Perhaps, central bankers do read The Money Illusion but they also read things which many readers of Money Illusion do not read. For example – See ‘Money and Collateral’ by Manmohan Singh & Peter Stella. Or, ‘Negative money multipliers’ by the same authors. Or anything by Perry Mehrling.

2. July 2012 at 23:45

Ritwik,

“Perhaps, central bankers do read The Money Illusion but they also read things which many readers of Money Illusion do not read. For example – See ‘Money and Collateral’ by Manmohan Singh & Peter Stella. Or, ‘Negative money multipliers’ by the same authors.”

Coincidentally I read “Velocity of Pledged Collateral – Analysis and Implications” and “Money and Collateral” today. I had gotten the impression beforehand from some PK/MMT types that these papers were highly damaging to the MM point of view.

Instead I came away with an enourmous sense of ho hum, what’s the big deal. Yes, they think people should pay more attention to pledged collateral, and they advocate more Qualitative Easing. But so what, so does Evans and Tarullo. This was supposed to blow my mind?

3. July 2012 at 00:41

Jim Glass: bank shareholders are not the problem.

3. July 2012 at 00:51

Mark

I think the key insight of those papers is not simply the policy recommendation of ‘let’s do more qualitative easing’. It hits deeper at the ‘what is money’ and ‘what is liquidity’ debates, while at all times being able to maintain the difference between money and credit. I see it as palatable to both the monetarist and the MMT povs, as long as they each keep an open mind without getting caught in the old categories of endogenous vs exogenous, zero interest vs. interest bearing, credit is important/unimportant etc.

Think of it as an extension of Goodhart’s point about the importance of monetary aggregates, properly defined, even in monetary regimes where the instantaneous stock of money, again properly defined, is endogenously determined.

I also suggest Mehrling’s framework of the hierarchy of money – http://www.ieor.columbia.edu/pdf-files/Mehrling_P_FESeminar_Sp12-02.pdf

http://economics.barnard.edu/sites/default/files/inline/what_is_monetary_economics_about.pdf

I consider the Singh/Stella contributions as subsumable under this framework. Think of money, credit and medium of exchange as conventionally defined to be category mistakes, as Nick Rowe would say. There is ‘ultimate money’ and money-derivatives. There are means of payment, and promises to pay. Singh/Stella can also be viewed as an explanation of how interest on reserves doesn’t change much by itself (though the right interest on reserves – which should be negative currently – may still matter). I think these are important challenges to the monetary transmission mechanisms debate, which goes much beyond the old, tired ‘loans create deposits’ challenge.

Incidentally, both Mehrling and the IMF/BIS people see themselves as reviving an old tradition in the theory of monetary policy/ central banking, which they believe would be recognizable to someone like Ralph Hawtrey. I find it interesting that what the market monetarists get from Hawtrey is the efficacy of nominal devaluation and the sticky wage theory of the business cycle, while what someone like Mehrling gets is so orthogonal to it.

3. July 2012 at 04:30

The FT is arguing that negative IOR is contractionary:

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2012/07/03/1067591/the-base-money-confusion/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter

The world is apparently trying to see to it that Scott won’t get to shorten his to-do list.

3. July 2012 at 04:46

I’m not sure why Williamson makes such a big deal about the seasonality of GDP. That seasonality is normal and quite easy to plan for. You wouldn’t be targeting a 5% in NGDP increase each quarter over the last, you would be targeting a 5% increase in NGDP over that same quarter (or 6 week period) from LAST YEAR, which takes care of the seasonality and still gets you on a stable growth path.

Retailers deal with this all the time, as their sales patterns are even more pronounced than the overall economy. They look at comps to see how they’re doing compared with last year.

Why is this an issue?

3. July 2012 at 05:45

you know, if this is the worst he can come up with we are in good shape.

as i mentioned on an earlier thread, the debate about whether PLT or NGDPLT is optimal is model (and therefore assumption) dependent. I doubt anyone will ever convince people that the labor market works this or that way, nominal debt markets work this or that way, seeing as how this debate has been raging for a gazillion years and many economists insist on seeing structural unemployment everywhere**. I think that the real question is not whether PLT or NGDPLT is “optimal” but what the costs are of suboptimal policy. the costs of pursuing PLT when ngdplt is optimal are much higher than the costs of pursuing ngdplt when PLT is optimal.

** I doubt the structural employment hypothesis, i.e. that it every really exists: when demand for labor is high enough, employers hire and train employees. That’s old fashioned OJT. Structural employment might temporarily raise frictional unemployment, but its amazing how people who need to work and employers who need to hire find ways to adapt.

3. July 2012 at 05:45

But even Krugman eventually conceded that higher inflation expectations are higher inflation expectations, and it doesn’t much matter whether they occur for the right or wrong reason.

I think it does. If they occur as a result of bad reasoning and the faulty informal models or background beliefs of market practitioners, the results are not likely to be robust, and will occur only so long as those cognitive deficiencies persist.

By now, many people have figured out that stuffing bank reserve accounts full of excess reserves does not drive additional spending and lending. So the next time it is used, the results of QE might be more ho-hum.

You can’t count on future recurrences of the Austrian inflation vapors every time the bank says QE. By now, even the Austrians have figured it out.

3. July 2012 at 05:51

What I find incredibly frustrating with SW’s model based arguments is that they seem to confuse an absence of evidence for evidence of absence. I find it surprising that SW, in his masterful expertise with models, doesn’t go down the line on a variety of models to explain how NGDP targeting fails in each of them. It would accord to his comparative advantage quite nicely.

Another thing I find weird about SW’s criticism is his focus on NGDP futures targeting. He seems to implicitly accept other Fed actions, whether QE, forward guidance, or lowering IOR, would be fully effective. These measures would then be the concrete steppes to get to NGDPLT. Note that in this transition, a lot of macroeconomic variables would be moving a lot. Would this “uncertainty” be any worse than a slightly uncertain overnight interest rate? It seems doubtful.

As an extension of the Evans proposal that can act as a quasi-NGDP target, a Soltas post a few weeks ago on rates and levels (http://esoltas.blogspot.com/2012/06/doing-its-level-best.html) brought up the possibility of targeting the rate change in unemployment along with the level of the CPI to align the rates/levels targeted along with what the Fed has control over. The Fed can’t control the level of employment (natural rate hypothesis), but has full control over both the rate and level of prices. I extended this as the way Soltas described his target made it sound like a quasi-NGDP target. The rate change in employment could feed into Okun’s law, and inflation plus the growth rate would equal NGDP. I took a look at this yesterday (http://synthenomics.blogspot.com/2012/07/levels-and-rates-to-fill-ngdp-data-gap.html) and found a pretty nice relationship.

NGDP Growth ~ YoY Headline CPI Inflation * 0.5 + YoY Percent Change in Nonfarm Employment + 3

It tracks NGDP growth quite well, even when calibrated on data before 2007 and tested on the 2007-2012 time period. Interestingly enough, the proxy exhibits less volatility than the actual NGDP growth statistics, so it actually tells the Marcus Nunes story much more clearly. There seems to be a wide variety of “pseudo-NGDP targets” out there, so SW’s flat out rejection of NGDPLT seems to also reject the “alternative” NGDP targets. I’m not sure what model he’s hiding behind to justify his evasiveness.

3. July 2012 at 06:06

Liberal Roman, Yes, that’s discouraging.

dtoh, Yes, there are other things they can do.

Jim, Thanks for the link. And I didn’t know that about Acemoglu.

Blair, I agree, I don’t think that’s even fair to Krugman.

Saturos, You said;

“Actually, “most people” just get scared when they see prices spiralling upwards at the grocery store.”

Yes, but I was referring to “most people” among the 3% of the US population that understands the Fed drives inflation over the long run. That group is upset about the impact on saving and investment.

I don’t folow the rest of your comment. I think everyone would agree that wages are not very flexible over the seasonal time scale, and also that hours worked are highly seasonal. But those fluctuations may still be optimal, i.e. would occur even if wages were more flexible at seasonal frequencies. Not so for cyclcial fluctuations.

Your other comments are excellent.

Ritwik, Obviously his estimates on NGDP shocks are very different from those used by the market monetarists. I’d check out Marcus Nunes’s graph, he shows a reduced NGDP volatility after 1984. Since the last 5 years on Williamson’s graph look very dubious to me, I’m inclined to think that he’s detrended the series using assumptions that distort the result.

If you simply use a 5.5% trend line for the Great Moderation (post 1985) things look vastly different. NGDP is quite smooth until 2008, then falls off a cliff. I have no idea why Williamson gets such different results, perhaps its the HP filter.

I have no idea what your comment about seasonality not being efficient means. Are you claiming it’s efficient to grow strawberries in January, or build houses in the snow? Or to spread Chistmas over the entire 12 months of the year?

Mark, You said

“Thanks to that paper I discovered that it appears to be a regular empirical fact that aggregate financial (dividends, interest and rent) income tends to rise sharply while business income declines after contractionary monetary policy shocks.”

In the Great Contraction I am almost certain these types of income declined, and income became more equal in America. The recent recession also made income more equal than in 2007. So I’m puzzled by this claim.

If the left favors ultra-tight money causing millions to be unemployed because they think it makes income more equal, then they are even more clueless than I thought. At least Krugman still understands that’s nonsense.

I certainly agree with your comment about RGDP and NGDP.

Ritwik, You said;

“2. Scott argues that in the long run, the price level depends on the quantity of money, not nominal income.”

I don’t recall ever making that argument. I focus on M and NGDP, and ignore the price level.

You said;

“Formulations of the QTM are not so much a causal mechanism as simply an equation.”

I think you are confusing it with the equation of exchange. The theory part claims to explain the effects of various central bank policy options. I’m not going to defend all versions of the QTM, but any of the smarter proponents are aware of the endogeniety issue.

Bob, Every time I try to break away, they keep pulling me back.

Brian, I agree that’s it’s not a big deal at all.

3. July 2012 at 06:33

My recollection of Williamson is that he borrows from RBCT the notion that what might look like “cyclical” demand-driven recession inefficiencies would well be the efficient response to some real shock (he views the banking/finance system as an important “technology” that sometimes stops working properly) and that most AD theorists assume the conclusion rather than demonstrating it to his satisfaction.

Why is Thoma complaining about MMs not responding to Andolfatto? Josh Hendrikson has had a detailed back-and-forth. Bill Woolsey has responded to Andolfatto then and Williamson now.

3. July 2012 at 06:36

Ritwik, The graph in the post that Yichaun provides shows how NGDP growth was more stable during the Great Moderation, than either before or after.

dwb, I mostly agree. I view structural unemployment as being mostly caused by governemtn labor market policies, as in Europe.

Dan, Whether QE works or not depends on whether central banks want it to work or not. If they want it to work, they’ll signal it’s somewhat permanent. If they don’t, they won’t. That’s why I say it’s a clumsy policy—better to explicitly set your policy goals and let M be endogenous.

Obviously it also depends on whether it’s more or less than expected.

Yichaun. Good post. But note that the coefficient on inflation is only 0.5%, which means it’s out of sample properties will be limited, as it will breakdown at very high inflation rates.

I don’t see the policy lags issue as a big problem, as I favor targeting the forecast, even if we are not doing NGDP futures targeting.

3. July 2012 at 06:38

Wonks, I thought no one believe the pure-RBC view any longer. Certainly no one who calls himself a “monetarist.”

I wondered about Thoma as well. Didn’t Nick Rowe also reply to Andolfatto?

3. July 2012 at 06:45

The FT Alphaville post makes some interesting points. It’s hard to dispute that a negative IOR is tantamount to shrinking the money supply. As the post mentions, this could be offset by simultaneous Fed asset purchases (QE), but advocates of negative IOR don’t often mention this requirement. So what would a combined regime of negative IOR and asset purchases accomplish? For one thing it would incentivize people to hold physical cash rather than bank deposits. This would presumably be inefficient and introduce frictions into economic transactions. So that would be contractionary. It might also spur purchases of gold and other hard assets. So I guess that would be good for the mining industry, but again not necessarily great for economic activity in general. The real question is what effect it would have on banks’ behavior. At first blush, it appears that banks would try to reduce the amount of reserves they hold with the Fed, but since that is basically a closed system, it amounts to a game of hot potato, with each bank trying to pass off its reserves to the next. So each individual bank would have an incentive to lend, but looking at the system as a whole, lending would have to decrease (since the reserves would be shrinking) unless offset by Fed asset purchases. Assuming it would be offset, the net effect should be to push banks out of low-yielding assets and into higher-yielding (i.e. riskier) loans. This is assuming they wouldn’t just build huge vaults filled with cash and hire security guards to watch them (presumably good for the private security industry but not economic activity in general). So, yes, negative IOR could help, but it might be a bumpy road to get there.

3. July 2012 at 06:59

“Is there anything worse than an interest rate hawkish progressive? Yes, I’m talking about you Simon Johnson.”

Liberal that’s pretty much SW too, isn’t it? A hawkish progressive who hates Krugman more than anything.

3. July 2012 at 07:00

Scott good to have you back. I was worried about you-seriously. I mean in all the time I’ve ready Money Illusion-admittedly only going back to November-I’d never seen you take off time. Usually you annoucne you’re going to cutback but you never actually have done before.

That you responeded to SW shows you still have the same old fight. If you hadn’t that would have been a bad sign.

My take on SW is he’s a pretty smart guy but also pretty petty. What makes him tick is his vanity. If you offend his vanity you are dead to him. That’s why he hates on Krugman so mcuh because of his comments back in 2009 that “Macro has failed.”

SW took that real personally. My guess is that NGDPT is largely the same thing-it offends his vanity. Here he gives the game away:

“It will be a cold day in hell when the Fed adopts NGDP targeting. Just as the Fed likes the Taylor rule, as it confirms the Fed’s belief in the wisdom of its own actions, the Fed will not buy into a policy rule that makes its previous actions look stupid.”

From his stand point read “SW” where he writes “Fed” as his vanity is about his standing in Macro and as an integral member at the Minneapolis Fed.

I’m not necessarily saying all his questions are wrong but his objection is coming from there. When dealing with someone like SW always follow the vanity to understand what’s driving him.

That’s probably how a lot of people in powerful institutions are-they don’t like criticisms of their insitution by those they see as outsiders-and therefore not worthy.

Still Frideman was able to get it done insitutionally. As Friedman 2.0 you have to ask yourself “What would Milton do?”

Like you said it’s all about winning over the macroeconoimsts. So how did Milton do it?

3. July 2012 at 07:00

It is good to have a monetary policy that works even during “periods where NGDP falls far below trend (1932 and 2009).” But let us note in passing that with NGDP targeting 1932 and 2009 wouldn’t have happened: a fall of NGDP *far below trend* would require an unforeseen cataclysm.

3. July 2012 at 07:02

Scott already knows this but Nick Rowe has also replied to Andolfatto.

3. July 2012 at 07:12

I think the MMTers also think negative IOR is contractionary isn’t that right Dan Kervick?

3. July 2012 at 07:23

my question for the day: should bob diamond be up for mervyn king’s job? diamond seems to be better at manipulating interest rates. (that’s a joke; i know interest rates don’t show the stance of monetary policy…)

3. July 2012 at 07:27

Scott,

“In the Great Contraction I am almost certain these types of income declined, and income became more equal in America.”

All kinds of income declined in the Great Contraction but some kinds declined less than others. Obviously Olivier Coibion et al is stating financial income (what the CBO and others calls capital income) goes up during contractions but I that may only be true if the tightening of monetary policy is mild (a la the Great Moderation):

Capital income (dividends, interest and rent) share of personal income % (Source: Piketty and Saez) and NGDP growth rate and implicit price deflator

Year-Share-Deflator-NGDP

1929—21.3—–0.4—–6.4

1930—21.8—(-3.7)-(-12.0)

1931—22.0–(-10.4)-(-16.1)

1932—23.2–(-11.7)-(-23.3)

1933—21.1—(-2.7)–(-3.9)

1934—19.0—–5.6—-14.7

1935—17.4—–2.0—-11.1

1936—17.6—–1.0—-14.3

1937—17.1—–4.3—–9.7

Note that shares of capital income vary inversely with inflation and the rate of NGDP growth.

It goes without saying the bottom 90% are highly dependent on wages and salaries for their taxable income. The top 10% on the other hand are much more dependent on capital and capital gains income. In 1929, which was a record year for capital gains during the pre-World War II period, capital gains nevertheless only ranged from 7.6% of all income for P90-95 to 22.7% of all income for P99.99. Capital income on the other hand varied from 18.9% of all income for P90-95 to 54.7% of all income for P99.99. A graph showing the distribution the sources of noncapital gains income for the top 10% in 1929 and in 1998 (Piketty and Saez) is here:

http://noumignon.livejournal.com/37706.html

3. July 2012 at 07:28

(continued)

Let’s take a look at the share of noncapital gains personal income derived from capital income from 1929-37. But as we do, keep in mind that capital gains income as a share of personal income fell from 7.7% in 1929 to 2.6% in 1930 and never exceed that level with the exception of 1936 when it was 3.7%. A graph showing the proportion of capital gains income to all personal income is here:

http://www.kentwillard.com/photos/graphs/net-capital-gains-as-percent-of-individual-income.jpg

The following is from Piketty and Saez (capital gains in share) and the BEA:

Pretax Taxable Personal Income share (%) of the bottom 90% and NGDP growth and the GDP implicit price deflator

Year-P0-90-Deflator-NGDP

1929—56.0—-0.4—–6.4

1930—56.8–(-3.7)-(-12.0)

1931—55.6-(-10.4)-(-16.1)

1932—53.6-(-11.7)-(-23.3)

1933—54.8—(-2.7)–(-3.9)

1934—54.8—–5.6—-14.7

1935—56.5—–2.0—-11.1

1936—54.9—–1.0—-14.3

1937—56.5—–4.3—–9.7

Notice that income shares of the bottom 90% generally trended downward with deflation and falling NGDP and did the opposite with inflation and rising NGDP. The top 10% on the other hand saw their income shares increase during the contractionary period. In fact the split in income shares in Hoover’s last full year of 1932 was the lowest for the bottom 90% and the highest for the top 10% on record until 2005.

3. July 2012 at 07:33

On second thought, I think the first order response of banks to negative IOR would just be to pass this cost on to their depositors. Even if they don’t want to explicitly charge depositors negative interest, they might accomplish the same thing through a combination of effectively zero interest and higher fees. So I’m not even sure it would spur lending per se.

3. July 2012 at 07:47

Scott,

“The recent recession also made income more equal than in 2007. So I’m puzzled by this claim.”

Capital income reached its recent peak as a percent of personal income (19.5%) in 2008Q3. It was hit harder than other sources of income in 2009 but has been recovering faster since. So you’re right the pattern has completely broken down more recently.

Here is capital income, NGDP growth rates and inflation for the period from 1961 through the present day:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=78612&category_id=0

Note however that capital income was rarely more than 14% of personal income during the age of accelerating inflation and has been always higher during the era of disinflation.

3. July 2012 at 07:52

Mike Sax,

“Liberal that’s pretty much SW too, isn’t it? A hawkish progressive who hates Krugman more than anything.”

That’s the second time I’ve seen you make that claim. Steve seems very apolitical to me. What makes you think he considers himself a liberal or a progressive?

3. July 2012 at 07:55

Ritwik:

1. The same “long run” we assume when drawing the LRAS curve. I.e. the one before which Keynes expected everyone to drop dead. (If I really wanted to be snarky, I’d say that was easy for Keynes to write, since he never expected to have kids…)

2. My version of the QTM has three premises:

a) (identity) MV = PY

b) (equilibrium condition) M = kPY

c) (postulate) changes in V and k are independent of changes in M over the long run.

The conclusion is that M drives nominal income in the long run.

I think rational expectations are equivalent to adaptive expectations unless people have better information. So, the public might assume that the central bank was holding M constant. Then they would expect NGDP to be the same next year as this year, as people aren’t expected to want higher money balances (though if better information were available then a market forecast would reveal it) and every person’s spending of money is someone else’s income, savings = investment, etc.

3. My intuition has always been that the monetary base is the best single definition of money, a) because it’s the only kind that the Fed fully controls, and b) because in some sense all other forms of money are really the base itself circulating at higher frequencies. It’s kind of like string theory, where strings vibrating at this or that frequency are supposed to give rise to this or that quark, etc. So NGDP = M0 * V0, and also M2 * V2. So M2 = M0 * (V0/V2), which is a real rate of circulation. i.e. if we multiply M0 by that frequency it effectively turns into M2. We say that commercial banks “create money”, but in reality whenever one bank pays another they have to transfer reserves, right? Not all of M2 can really be spent simultanaeously the way that M0 can, so it isn’t “really money”.

4. Why wouldn’t it? As Scott says, money is ultimately a commodity just like apples, and its price depends on supply and demand like anything else. Because it’s the medium of account, that price happens to be the inverse of the general price level. The only complication is that the flow supply of money equals the stock times its velocity, – but that velocity is determined by k which is determined by “real” factors in the long run (or any run, if trend inflation is high enough).

5. The causal mechanism is the excess cash balance mechanism, or the “hot potato effect”. Plus helicopter drops raise nominal wealth directly. And I think the fact that the Fed returns interest payments to the Treasury also produces a wealth effect, though I’m not sure. And then there’s negative IOR, if necessary. A currency redenomination or a Roosevelt/Svensson depreciation could be modeled via ECB and wealth effects, but I agree with Nick Rowe that what really happens is that we simply jump to the new equilibrium, like Daylight Saving Time.

I thought Patinkin was a hardcore Old Keynesian?

6. What exactly would I expect to learn from those articles? How would it be useful? (I’ve got Money and Collateral sitting on my computer, I’ve just never gotten around to reading it.)

3. July 2012 at 08:00

A number of interwar economists, including Hayek, advocated NGDP targeting.

Hayek was not consistent on this point. He argued in favor of preventing nominal incomes from falling sometimes, and argued against it other times, and, most importantly, at the end of his career, when he had an entire lifetime of considering all the various monetary theories and monetary regimes, he wrote a book [Warning:PDF] “Denationalisation of Money: The Argument Refined”, which was a treatise on the complete denationalization of money and allowing entrepreneurs to produce money in the private market.

In this book, he noted:

“Everybody knows of course that inflation does not affect all prices at the same time but makes different prices rise in succession, and that it therefore changes the relation between prices – although the familiar statistics of average price movements tend to conceal this movement in relative prices. The effect on relative incomes is only one, though to the superficial observer the most conspicuous, effect of the distortion of the whole structure of relative prices. What is in the long run even more damaging to the functioning of the economy and eventually tends to make a free market system unworkable is the effect of this distorted price structure in misdirecting the use of resources and drawing labour and other factors of production (especially the investment of capital) into uses which remain profitable only so long as inflation accelerates.”

So Hayek knew that the misdirection of resources and labor that accompany the inflation used in NGDP targeting, is damaging to the extent that it require accelerating inflation in order to be maintained.

Here’s a quote for Sumner the self-professed “pragmatist”, which is of course another word for political strategist, one who advises those who systematically initiate force and coercion thus creating perpetual losses, in order to “do good for society”:

“But the present political necessity ought to be no concern of the economic scientist. His task ought to be, as I will not cease repeating, to make politically possible what today may be politically impossible. To decide what can be done at the moment is the task of the politician, not of the economist, who must continue to point out that to persist in this direction will lead to disaster.”

Hayek would have repeated to Sumner that he ought to act like an economic scientist, rather than a political strategist. I agree.

Then there was Hayek’s criticism against continually increasing aggregate money expenditures:

“The chief root of our present monetary troubles is, of course, the sanction of scientific authority which Lord Keynes and his disciples have given to the age-old superstition that by increasing the aggregate of money expenditure we can lastingly ensure prosperity and full employment…It was John Maynard Keynes, a man of great intellect but limited knowledge of economic theory, who ultimately succeeded in rehabilitating a view long the preserve of cranks with whom he openly sympathized.”

The phrase “Increasing the aggregate of money expenditure” is what is now called NGDP.

Then there is his pseudo-Nobel speech where he argued against what is now called NGDP:

“The theory which has been guiding monetary and financial policy during the last thirty years, and which I contend is largely the product of such a mistaken conception of the proper scientific procedure, consists in the assertion that there exists a simple positive correlation between total employment and the size of the aggregate demand for goods and services; it leads to the belief that we can permanently assure full employment by maintaining total money expenditure at an appropriate level. Among the various theories advanced to account for extensive unemployment, this is probably the only one in support of which strong quantitative evidence can be adduced. I nevertheless regard it as fundamentally false, and to act upon it, as we now experience, as very harmful.”

Key words are “maintaining” and “appropriate level.” That is NGDP targeting. Hayek said this would be “very harmful.”

Finally, Hayek said this:

“Here my aim has merely been to show that whatever our views about the desirable behavior of the total quantity of money, they can never legitimately be applied to the situation of a single country which is part of an international economic system, and that any attempt to do so is likely in the long run and for the world as a whole to be an additional source of instability. This means of course that a really rational monetary policy could be carried out only by an international monetary authority, or at any rate by the closest cooperation of the national authorities and with the common aim of making the circulation of each country behave as nearly as possible as if it were part of an intelligently regulated international system.”

“But I think it also means that so long as an effective international monetary authority remains a utopian dream, any mechanical principle (such as the gold standard) which at least secures some conformity of monetary changes in the national area to what would happen under a truly international monetary system is far preferable to numerous independent and independently regulated national currencies.”

This is Hayek saying it would be beneficial if each country’s money supply, and hence aggregate spending, fluctuated as if it were part of an international monetary order. And that a mechanical principle such a a gold standard, is “far preferable” to numerous national currencies changing their respective money supplies (to target national NGDP or whatever).

———-

Imagine buying a boat and being told by the sales person that the steering works fine 99% of the time, and only fails in wild and raging typhoons. I don’t know about you, but a stormy day is when I most want the steering mechanism to work. And it’s during periods where NGDP falls far below trend (1932 and 2009) where I most want my monetary policy instrument to work. Given rates are at zero, and we need more stimulus, it seems an odd time to question my dissent from interest rate targeting orthodoxy.

See that? No discussion of pre-1932(1929) and pre-2009(2008) central bank monetary manipulation that distorted the price structure of the economy that made it appear as though it was necessary for the Fed to alter their money printing in order to “save” the status quo NGDP.

No discussion of how monetary manipulation is the very wild and raging typhoon that throws boaters off course.

As always, it’s just taking declines in spending as a given. As an inexplicable “nominal shock.” Take collapses in NGDP for granted, as a given aspect of the market, and you can instantly imply a non-market “solution”. Oh look, we have a Fed! How convenient. We can ask the Fed to counter-act this dark force we cannot explain, and in so doing, totally ignore the fact that the market driven decline in NGDP is a signal of instability caused by prior inflation from the Fed System! It’s perfect. Promote the cause of the problem as the only solution to the problem, and deny that “stable” inflation produces problems of its own. Up is the new down.

———–

I can think of several other options. For instance, the Fed could do lots more QE. The purpose of QE is to raise inflation and/or NGDP growth expectations. I’m sure there are lots of models where QE doesn’t work, but in the real world is does work.

It works at distorting the price system even further, yes. NGDP aggregation masks the relative changes that are brought about by inflation.

Not everyone’s incomes rise to the same degree. Not everyone’s business expands to the same degree. Inflation is a change in relative conditions. Crudely averaging out all these changes to get a single, nice, clean, pedagogical statistic, is reckless and makes errors in judgment inevitable.

No investor invests into, and no seller sells into, “aggregate spending.” Aggregate spending is not some freely floating collection of dollar bills “moving” around in the air, waiting to be plucked out by those who seek to earn money, where if this single value declines then “society” is worse off, and where if this value rises nice and stable, then “society” is better off.

Aggregate spending is not a driver. It is a result. If NGDP drastically falls, according to the market process, then this is a result of the same thing that caused the unemployment and idle resources. It’s not a cause for unemployment and idle resources. The more aggregate spending falls according to the market process, the more it should tell you that there are problems in the economy that need corrections BY the market process and only the market process.

Yes, if invisible aliens came down and confiscated 90% of people’s cash balances, then there will invariably arise a huge correction process as everyone adapts to the new money conditions. But this is a piss poor analogy for the economy, because in the real world economy 2008 on, individual market actors decided to reduce their spending despite the Fed not destroying dollars like invisible aliens. You can’t say the Fed “failed to inflate”, because that disrespects the market process that is proximately the cause for the reduction in spending. The Fed is not in charge of my spending. It should not be in charge of anyone’s spending. If I and millions of others reduce our spending, then this is not the Fed failing, this is the market process succeeding.

Aggregate spending is an EFFECT of individual investors investing and individual sellers selling. It is an abstract concept that has no bearing on the individual investor and seller. Individual markets can go up and down, independent of NGDP movements. If there is correlation between NGDP and employment, you can’t refuse to conclude that NGDP decreases because employment and investment spending decreased, rather than vice versa, unless you have an a priori economics theory, which proves that aggregate spending is the driver for employment, output, and economic progress. Hayek disagreed that it was. He said it was a Keynesian dogma.

What ensures employment is not aggregate spending, but economic coordination. Prices can, and in a market devoid of Fed intervention they will, fall to clear expanding markets. Wages are sticky in large part because of inflation. It is a gross error to believe that inflation is needed because wages are sticky.

Fed policy statements hinting at QE had an obvious and unmistakable effect on asset prices in late 2010, including TIPS spreads.

There was also a jump in the equity markets after experiencing a recent fall…probably the actual motivation for QE in Nov 2010.

…higher inflation expectations are higher inflation expectations, and it doesn’t much matter whether they occur for the right or wrong reason. In fairness, even I have some doubts about whether QE is the best way to go. It’s a clumsy tool. And although (I believe) I was the first to publish a paper advocating negative IOR, I also have doubts about whether that’s the appropriate policy. Instead, I think by far the best option is to set a NGDP target, and more importantly, to engage in level targeting. This sort of policy announcement would immediately boost NGDP growth expectations (or reduce real interest rates if you prefer to model things that way.)

A “boost” to NGDP growth expectations cannot be made good unless there is actual additional QE. People cannot spend the additional money they haven’t gotten yet, until they get it. The argument that mere words can increase current spending to whatever level is announced as the official target, presumes cash balances are infinite.

Aggregate spending in the present is a function of how much money exists in the present, not how much money will exist in the future.

If the Fed had done that back in early 2008 we never would have hit the zero bound in the first place, as expected NGDP growth would have been far higher, and nominal interest rates are strongly impacted by changes in expected NGDP growth (but also deviations from trend.)

At what cost? Why do you keep ignoring the costs and presenting NGDP targeting as a panacea?

If the Fed had inflated even more in late 2008, then they would have distorted the price system even more, and encouraged even more malinvestment.

This chart shows the extent of the malinvestments accumulated during last boom.

Notice how much more the construction and durable goods industry suffered relative to service and retail. This is because too many scarce resources and too many scarce labor hours were devoted to construction and durable goods, rather than other less capital intensive stages of production.

The larger relative drop in construction and durable goods as compared to retail and service at least healed some of the accumulated distortions (of course the healing process was halted because the Fed reinflated once again, as per usual). If the Fed inflated even more than they did, then not only would resources and labor remain in physically unsustainable lines, there would be even more errors piled on top of the old ones.

NGDP targeting completely ignores all this, and pretends is only a minor problem (that more inflation can solve of course).

That’s why countries like Australia don’t have to worry about the zero rate trap, they keep NGDP growing fast enough to avoid it.

Australia had to worry about accelerating money supply growth throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Money supply growth was less than 2% per year in late 1991. After years of inflation DISTORTING the price system, and hence the productive structure of Australia’s economy, the central bank found that it had to accelerate the growth in money supply to prevent the distortions from correcting (and thus prevent NGDP from falling). Thus, by early 2008, soon before the financial crisis, money supply growth was running at over 20% per year.

Accelerating money supply growth is not sustainable. At some point, even with constant NGDP growth targeting, an accelerating money supply growth is eventually going to overpower the central bank’s ability to target NGDP, and when that happens, the central bank will not be able to destroy money faster than it is being spent.

NGDP targeting does not bring about a free lunch. Communist central banking and a market economy are antithetical. It may take years, decades even if the people are convinced central banking works, but at some point, one or the other has to be eliminated.

———–

That makes no sense to me. During the 1980s and 1990s the Fed moved toward a rule (call it the Taylor Rule, inflation targeting, whatever) that made their previous high inflation policy of the 1970s look stupid. In fact if you speak to Fed officials they love to tell you how misguided Fed policy was during the Great Inflation, and how they’ve done a much better job since about 1983.

The 1970s only look “stupid” if you narrowly focus on price inflation, and you ignore other important factors, such as, among other things, the shadow banking system that has drastically accelerated starting around the mid-1990s. This portion of the financial sector has no deposits. Rehypothecated assets, repos, these liabilities can sustain a Ponzi expansion during the leveraging phase, but during a deleveraging phase, which is where we are now, it can’t. The total liabilities of this sector has been decreasing every quarter since March 2008. But it’s still large enough to act as a buffer against price inflation for the madhouse money printing the Fed has been engaging in since then.

————

Times change and macro theory never stops evolving.

….except for NGDPLT, right? It is the “optimal” macro-policy that makes fiscal policy moot, and the Fed no longer has to worry about its actions bringing about “large-scale” economic problems, right? NGDPLT is the end-game of all things macro, right?

Or is NGDPLT just another temporary flavor of the month, that will also be falsified/refuted just like you believe is the case for all the previously proposed macro flavors?

Times change, but economic laws applicable to actors don’t change.

Macro “theory” never stops changing because it is an ideological, thought-based game, that has no grounding to anything outside itself. Macro-economics is ultimately a game of manipulating words and phrases according to rules that are divorced from real world action.

In this context, in this thought-based field of inquiry, it is inevitable that as old macro-economists leave the field, and as new macro-economists enter the field, there will be a constant influx of unique “my personal rule is…” proposals, and hence “macro-economics” will appear to change over time.

Just consider how many branches of macro-economics there are: Keynesian, New Keynesian, Post Keynesian, Neoclassical synthesis, New classical, Disequilibrium, Monetarism, New Monetarism, Market Monetarism, New Growth, Modern Monetary Theory, New Synthesis…New, Neo, Post, Modern, it goes on and on…

Why the 57 different varieties? Are humans, economic laws, or anything else about the economy changing that would justify the constant change in macro-economic theory? Is the coordination dependent on the price system only relevant 1913-1936? Or 1930-1950? Is saving and investment only necessary in production during the industrial revolution? Is the optimality of a free market in money production only applicable to 1800-1845? Or 2045-2100?

Or is the problem with macro-economics more fundamental than you seem to realize? Could the problem be the philosophical approach: the methodological monism that plagues the field of epistemology? That it isn’t about the choice of particular variables in one’s monistic “model”?

Could it be that it was a giant mistake to believe that empiricist-positivism, which is so successful in the natural sciences, is also a valid epistemology for human action?

That just like it was wrong to believe constant growth price index targeting as the end-game of state controlled money production, so too is it wrong to believe constant growth spending targeting as the end-game of state controlled money production, for the same fundamental reason that is going over your Rorty-brainwashed head?

Still, I’d really like to know what stylized fact made all those US economists who were dismissive of the idea that the BOJ was out of ammunition in the late 1990s, suddenly come to the conclusion that the Fed is out of ammo. Is there some fact that disproved the previous conventional wisdom that I somehow overlooked?

You can glean the epistemological mindset of those who conceive of Fed action as an army of soldiers fighting a war: “The Fed is not out of ammunition“.

Maybe the problem of the economy is that it keeps getting shot at?

3. July 2012 at 08:03

Mark he told me he’s a liberal and that he supports Obama. I have no agenda to propogate a false rumor-this is from the horse’s mouth. His political affiliation is not a big deal except it’s strange to see an Obama supporter-so he claims-hate on Krugman that much.

My guess is as I suggested above-SW takes Krugman’s attacks on Macro very personally.

Your point about what Simon Johson was saying actually got me to reconsider.

3. July 2012 at 08:07

O Nate judging from Izabella’s piece she’s claiming it wont spur lending and she quotes from Peter Stella:

“Stella is currently the director of Stellar Consulting, an organisation that provides macroeconomic policy advice and research to central banks, governments, and private clients. He was formerly the head of the Central Banking and Monetary and Foreign Exchange Operations Divisions at the International Monetary Fund. He has co-authored a number of papers on the topics of money supply, collateral and risk-free assets.”

“He got in touch with FTAV because of what he feels is a gross misunderstanding in policy and journalistic circles regarding the nature of central bank reserves, and the myth that banks are not lending because they prefer not to.”

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2012/07/03/1067591/the-base-money-confusion/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter

“Reserves, also known as base money, can only be extinguished by the central bank as part of strategic balance sheet reduction policy. This in itself can only be achieved through outright asset sales, reverse repos, negative rates or to a lesser extent by auctioning term deposits.”

“It thus stands to reason that negative rates “” by reducing the central bank’s balance sheet “” are contractionary rather than accommodative when it comes to credit supply.”

3. July 2012 at 08:16

Dan, Whether QE works or not depends on whether central banks want it to work or not. If they want it to work, they’ll signal it’s somewhat permanent. If they don’t, they won’t. That’s why I say it’s a clumsy policy””better to explicitly set your policy goals and let M be endogenous.

Scott, if the point of QE is to influence inflation expectations, then whether it works or not has to do with the psychological states of the people whose expectations the Fed is attempting to influence. The issue is not just whether these market practitioners believe the QE will or will not be somewhat permanent. The psychological response also depends on what they think QE is in the first place.

If Ben Bernanke says he is going to buy the extra wax when he gets his car washed each week, and signals that this practice will now be permanent, that will obviously have no impact at all on inflation expectations, because nobody thinks what Ben Bernanke does or does not do to his car has any impact on the price level. Similarly, if people no longer believe that QE has first order effects on the price level by increasing the broad money supply, then the ability of announcements of QE to have a second order effect and accelerate inflation by influencing expectations is thwarted.

My contention is that in earlier rounds of public announcements and press reports about QE, there was a crude picture of QE presented as “running the printing presses” in a way which would increase the amount of broad money in circulation and accelerate inflation. Since people had a crude understanding of what QE is, then their expectations of the effect of QE might have been more manipulable in an equally crude way. But I suspect people are more savvy now, and they increasingly understand that QE just swaps in one kind of liquid financial asset for another in financial institutions’ assets thus increasing bank reserves, and that increases in the quantity of bank reserves do not necessarily lead to more lending and spending. In the past QE got some mileage out of the fact that it was somewhat novel and poorly understood, and therefore the slightly hysterical buzz among the hyperinflation worriers had an impact on the expectations of some market participants in some markets. I wouldn’t expect those impacts to occur again, even at the modest levels they occurred before.

3. July 2012 at 08:25

I think the MMTers also think negative IOR is contractionary isn’t that right Dan Kervick?

Mike, almost everything I know about IOR I learned from reading Scott Fullwiler. I believe Scott’s position is that IOR is just another tool for targeting the Fed Funds rate. I don’t know where Scott has addressed the issue of negative IOR. (He probably has, but I just haven’t read it.)

I once wrote a blog post in which I argued that the supposed mechanism for translating a negative Fed Funds rate into a negate rate on commercial bank lending is problematic, even in the hypothetical scenario of a cashless society in which all broad money exists in the form of commercial bank deposit balances. But I don’t know if any of the MMT economists have offered an opinion on the subject.

3. July 2012 at 08:28

Dan I just read the post over at Alpha which seems to suggest this is an MMT position

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2012/07/03/1067591/the-base-money-confusion/?utm_source=dlvr.it&utm_medium=twitter

“Reserves, also known as base money, can only be extinguished by the central bank as part of strategic balance sheet reduction policy. This in itself can only be achieved through outright asset sales, reverse repos, negative rates or to a lesser extent by auctioning term deposits.”

“It thus stands to reason that negative rates “” by reducing the central bank’s balance sheet “” are contractionary rather than accommodative when it comes to credit supply.”

3. July 2012 at 08:42

Blair,

“As an experienced central banker he no doubt has valuable insights to offer on transmission mechanisms, but it’s ridiculous to cast the Economist (and Ryan Avent in particular) as a carrier of ignorance when they’ve done so much to propagate market monetarist ideas which completely transcend the caricature of QE that Grenville describes.”