Recent studies of the identification problem

My new book focuses on the question of how best to think about the stance of monetary policy. This is closely related to the “identification problem”, which is the problem of identifying monetary policy shocks.

Some of the earliest attempts to estimate the impact of monetary shocks resulted in what’s called a “price puzzle”. It seemed like easy money led to lower inflation, and vice versa. That makes no sense. (A similar problem occurs with fiscal policy, where deficit spending is often correlated with slower economic growth.) The trick is to find the exogenous part of monetary policy, not the response to economic conditions. Are interest rates rising because of tight money, or because of higher NGDP growth expectations?

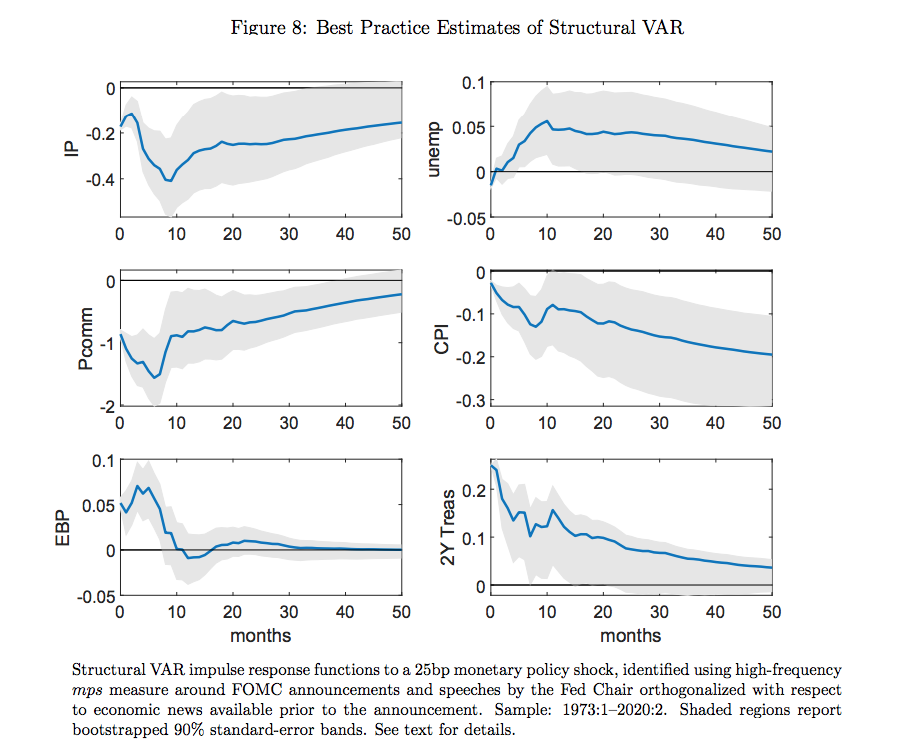

Some of the best work in this area has been done by Eric Swanson. In a new paper, Michael Bauer and Eric Swanson estimate structural VAR models in two ways. In the set of graphs below, the results on the right show a naive model, that doesn’t fully account for feedback effects. The response functions show the impact of a 25 basis point rise in the 2-year Treasury yield.

You can see the price puzzle in the left column (second row), where the CPI seems to rise in response to an increase in interest rates (assumed to be a tighter monetary policy.)

In the right column, the monetary policy shock (mps) is orthogonalized. This involves regressing the shock on previous macro data, and then using the residual (the unexplained portion) as the exogenous monetary policy shock. Now industrial production, the CPI, credit spreads (EBP) and interest rates all move as expected.

Another innovation in the Bauer-Swanson paper was to look beyond FOMC announcements, and also include market responses to speeches by the Fed chair. The combined effect of all of these innovations was to produce much more reliable estimates of the impact of monetary policy. Policy was shown to have a four times larger impact than observed in previous studies.

The following graph also shows the response of commodity prices and unemployment. Notice that the (sticky price) CPI barely moves at first, while (flexible) commodity prices immediately plunge by about 100 basis points. But after 50 months, both are down roughly 20 basis points, which is consistent with long run money neutrality:

Bauer and Swanson do a nice job explaining why the private sector has a difficult time predicting (and identifying) changes in the stance of monetary policy:

There are a number of plausible reasons to think that private-sector learning about the Fed’s monetary policy rule would be quite slow in practice, with the result that changes in αt would cause a persistently large discrepancy αt − at . First, learning about a persistent component (αt) from a noisy time series (it) is difficult and happens only gradually, with longlasting biases in beliefs; see Farmer, Nakamura and Steinsson (2021) for a recent discussion. Second, the private sector in reality faces a multidimensional learning problem: Realistic policy rules are of course multivariate, requiring the public to learn about several parameters at once, which greatly slows down the learning process (Johannes et al., 2016). Third, the private sector must form beliefs about which macroeconomic and financial variables enter the Fed’s monetary policy rule, i.e., about its functional form. Fourth, the Fed’s monetary policy rule could contain nonlinearities—which we have also abstracted from here—so that, in practice, the Fed responds most aggressively to the economy when the economic data is most extreme. These extreme events occur only very rarely, so it is extraordinarily difficult for the private sector to learn the Fed’s true responsiveness to the economy during these rare episodes.

Interestingly, Bauer and Swanson found that Fed speeches had a surprisingly small impact on the stock market:

The last two columns of Table 3 report the estimated effects of Fed Chair speeches on financial markets. Two-year and five-year Treasury yields respond almost identically to Fed Chair speeches as they do to FOMC announcements, while ten- and 30-year Treasury yields respond even more strongly. The R2 for Fed Chair speech effects are also even higher than those for FOMC announcements. Together, these observations confirm the general point in Swanson and Jayawickrema (2021) that speeches by the Fed Chair are even more important for the Treasury market than FOMC announcements themselves. By contrast, the response of the stock market is substantially weaker, with an R2 around 3 percent. The modest stock market response to Chair speeches is somewhat puzzling in light of the fact that monetary policy typically has pronounced effects on the stock market (Bernanke and Kuttner, 2005; G¨urkaynak et al., 2005). One possible explanation is based on information effects: Speeches by the Fed Chair could potentially have larger information effects than FOMC announcements, given the extensive conversations the Chair is having with the public or Congress about the Fed’s outlook for monetary policy and the U.S. economy. . . . Another explanation is that other news besides the Chair’s speech could have moved interest rates and stock prices during the event window.

I wonder if this difference might also reflect the fact that FOMC announcements primarily move rates via the “liquidity effect”, that is, where higher interest rates represent tighter money. Perhaps Fed speeches also impact rates via the Fisher effect. Thus the speech might convey information about the chair’s longer run views on the appropriate monetary regime. In that case, higher rates can be associated with easier money.

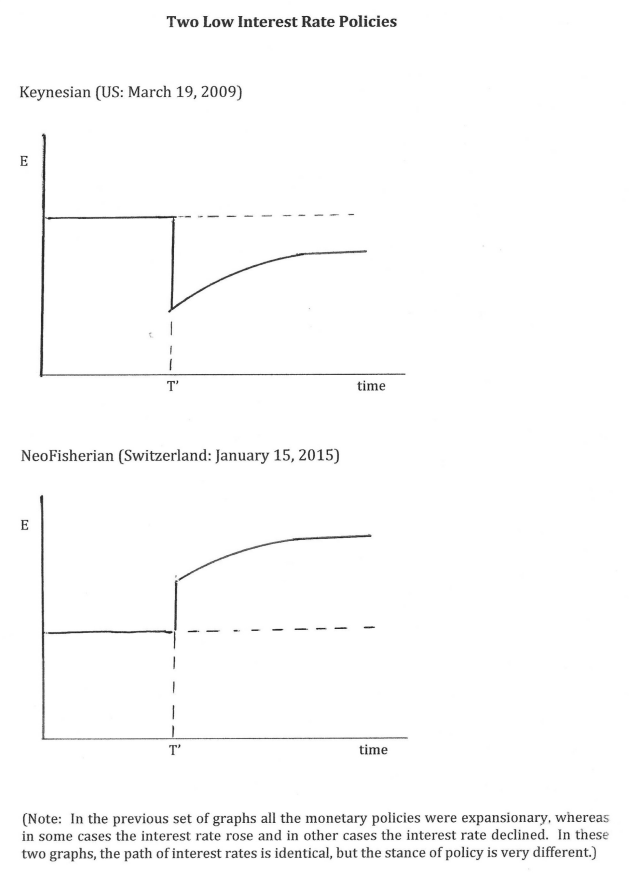

Here it might be useful to review a couple graphs from my new book, which show two possible expected exchange rate paths after a monetary shock:

These two money announcements have an identical impact on interest rates. Due to the interest parity condition, both reduce the nominal interest rate for a period of time. But in the first case the shock produces long run currency depreciation, and hence is expansionary. This is Dornbusch overshooting. In the second case, there is long run currency appreciation, and hence the shock is contractionary.

If you think of monetary policy as moving the actual interest rate relative to the natural rate, in the first case the market rate has been reduced, without any necessary change in the natural rate. In the Swiss case from 2015, the sharp currency appreciation caused the natural interest rate to fall even more sharply than the actual interest rate, hence policy became tighter.

The ECB recently published a very interesting paper by Marek Jarociński, which looks at these issues using a slightly different approach. I’m pretty weak at econometrics so I’m not qualified to provide an overall evaluation of the paper (or Bauer-Swanson), but I like the way Jarociński thinks about these issues. Here’s the abstract:

Fed monetary policy announcements convey a mix of news about different conventional and unconventional policies, and about the economy. Financial market responses to these announcements are usually very small, but sometimes very large. I estimate the underlying structural shocks exploiting this feature of the data, both assuming that the structural shocks are independent and relaxing this assumption. Either approach yields the same tightly estimated shocks that can be naturally labeled as standard monetary policy, Odyssean forward guidance, large scale asset purchases and Delphic forward guidance.

I like this. It’s not just a question of how much the interest rate changes, there are qualitative differences between various types of monetary shocks. Again, if we use the market rate/natural rate language, monetary shocks can move both the market interest rate and the natural interest rate.

In my research on the Great Depression, I concluded that extremely large shocks provided an unusually important source of information about the structure of the economy. Here’s Jarociński:

To identify the structural shocks I exploit a striking, yet hitherto neglected feature of the data. Namely, financial market reactions to FOMC announcements are usually very small, but sometimes very large, i.e. they have very fat tails, or excess kurtosis. This feature implies that the data may contain information about the nature of the underlying structural shocks. Given the importance of the Fed policies, it is vital to exploit this available information as well as possible. Previous literature has ignored it, treating the shocks explicitly or implicitly as Gaussian. This paper is, to my knowledge, the first attempt to tap this valuable source of information.

And here’s how he identifies the four types of shocks:

More in detail, the baseline model expresses the surprises (i.e., the high-frequency reactions to FOMC announcements) in the near-term fed funds futures, 2- and 10-year Treasury yield and the S&P500 stock index as linear combinations of four Student-t distributed shocks. It turns out that these four shocks are very precisely estimated and ex post have natural economic interpretations. The first shock raises the near-term fed funds futures, with a diminishing effect on longer maturities, and depresses the stock prices. It can be naturally labeled as the standard monetary policy shock. The remaining shocks do not meaningfully affect the near-term fed funds futures. The second shock increases the 2-year Treasury yield the most and depresses the stock prices. It can be naturally labeled as the (Odyssean) forward guidance shock. The third shock increases the 10-year Treasury yield the most and plays a large role in some of the most important asset purchase announcements. It can be naturally labeled as the asset purchase shock. The fourth shock has a similar impact on the yield curve as the Odyssean forward guidance shock, but triggers an increase, rather than a decrease, in the stock prices. Therefore, this shock matches the concept of Delphic forward guidance introduced by Campbell et al. (2012).

I welcome all of these studies, partly because they support my intuition that monetary policy (including forward guidance and QE) are much more powerful than many people seem to believe. We have a monetary regime that when combined with the dominant theoretical framework (roughly IS-LM) is almost ideally suited to making monetary policy appear less effective than it actually is.

On the other hand, I don’t think we’ll ever be able to resolve the key macro policy problems using this approach. Policy is too complex—it’s about both Fed errors of commission and omission, what are often extremely hard to identify.

Instead, I favor moving toward a regime where we collapse the monetary policy indicator, instrument and goal into one variable—NGDP futures prices. Ideally, NGDP futures prices would be the policy instrument (the thing we target), the policy indicator (the thing we look at to determine the current stance of policy) and the policy goal (with the goal being say 4%/year growth in NGDP futures prices, level targeting.)

Then we can stop doing all these SVAR models.

HT: Ben Southwood.

PS. I also comment on the Bauer/Swanson paper over at Econlog.

Tags:

19. April 2023 at 02:36

Scott,

I am sceptical a (deep) ngdp futures market can exist. Apart from speculators I do not see the reason anybody would want to buy or sell these in size. who are natural buyers and sellers of these instruments?

In well functioning futures markets you have commercial and financial buyers, i.e. there is direct (importatnt: direct) link between the real world and the price of the underlying.

No company is directly exposed to NGDP, a constructed and unobservable series. How will the costs and sales of, say, NIKE change as a function of NGDP? – I am afraid this is a very unstable correlation. Nike cannot hedge anything with NGDP futures and has very limited use by it.

I do not see how the Fed buying NGDP futures from a few select speculators results in satisfatory monetary transmission.

Last, even if a well functioning market exist, there still is the issue, well documented in financial economics, that futures prices are NOT good predictors of actual outcomes. There is no a priori reason to assume this would be different in this case..

19. April 2023 at 04:21

Great post. Gives me some more to read.

19. April 2023 at 06:55

Viennacapitalist

I agree wholeheartedly, NGDP targeting is a great idea, NGDP futures markets is a fools errand. Beyond the issues you just mentioned the impact of volatile time varying risk and liquidity premia priced into these markets would make them no more useful as a predictor than what can currently be found in markets and macro data.

Just look at moves in TIPS breakevens around economic shocks. They’re clearly moving a ton on liquidity premia which make it hard to disaggregate the actual inflation prediction. And those are markets with much more real users and depth than NGDP can ever hope to have.

19. April 2023 at 07:20

Vienna and FutSkeptic, Those comments have no bearing on what I am proposing. Check out one of my papers on the “guardrails” approach to NGDP futures markets. It does not in any way require a large or highly liquid market. Indeed it doesn’t require any trading at all.

19. April 2023 at 07:56

It would have been interesting if the Jarociński paper included the dollar as another a factor.

19. April 2023 at 15:04

I dream of a day when monetary policy leaves no traces of “shocks” to be measured. Maybe because of an NGDP futures tool.

19. April 2023 at 20:46

How about leaving your hands off the market.

Everyone needs to start using crypto and refuse to fiat.

And when they ban it, ignore them. Let’s see if they will turn off the electricity, because that’s the only way the monopoly monetarists can stop it.

My guess is they won’t…

It’s the way to freedom folks. Just use crypto.

19. April 2023 at 23:34

I wonder if monetary policy is really “long-term neutral.”

Seems to me a bad monetary policy can suffocate a nation for generations, or, conversely, lead to hyperinflation and even social-economic disorder very difficult to repair.

A human might have 50 earning years. Take away 20 of those years, and, for that wage-earner, bad monetary policy was not long-term neutral.

Also, let us assume a national economy can grow at a certain limit on the upside. Call it 3%.

If monetary policy stagnates growth for 10 years, then that 30% GDP expansion is lost forever.

The nation can right the economic ship, and start growing at 3% again, but can never make up lost ground.

Also, assume a nation with a demographic bulge in its labor force. If they are not working in their productive years, that labor output is lost forever. They are retired and just consuming.

Unfortunately, what is true is that monetary policy cannot improve technology, work ethics, government regs and taxes, etc.

Monetary policy cannot make an economy grow faster than the “best case.”

Seems to me monetary policy can be “long-term negative.”

20. April 2023 at 07:48

Re: “the “liquidity effect”, that is, where higher interest rates represent tighter money.”

That’s wrong in the present economy. When you get a surge in the money supply, it is typically followed up by a 3-month surge in the transaction’s velocity of circulation. But Vt doesn’t fall. It generates momentum.

And one thing increasing momentum is the shifting by saver-holders from bank deposits to MMMFs. This increases the volume of loan funds, or velocity, but not the volume of money.

And the neutrality of money is also wrong as it takes increasing volumes of Reserve Bank credit to generate the same inflation adjusted dollar amounts of R-gDp.

20. April 2023 at 07:58

The FED’s Ph.Ds. don’t know a debit from a credit, a bank from a nonbank. The money stock was misclassified (overstated) by MSBs between 1913 and 1980.

The correspondent balances of the S&Ls and CUs have been misclassified (overstated) since 1980.

The DIDMCA turned the thrifts into banks in 1980 and then included their liabilities in the money stock, but not their assets in commercial bank credit.

O/N RRPs are misclassified. Just eliminate paying counterparties on O/N RRPs and watch all hell break loose.

Large CDs should be included in the money stock, etc.

The money stock can never be properly managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit.

20. April 2023 at 14:10

Speaking of inflation, this caught my eye. What the heck is going on with transportation? Average gas prices are down 50 cents y/y so…

Did car prices suddenly jump? Is the fed looking at prices or at actual car payments in nominal terms including interest much more interest expense than they did a year ago?

https://media.licdn.com/dms/image/D5622AQGoafKg4YOfRg/feedshare-shrink_1280/0/1681303235568?e=1684972800&v=beta&t=RwrTw9D6ou5yaG_z9BAX1aqkK74DRs-bwiyxDkbnj7U

20. April 2023 at 15:16

Side question: If a nation followed the proper monetary policy, as defined by Scott Sumner, and it had tight labor markets for two generations, defined as a 130 job openings for every 100 job hunters.. would that nation move into hyperinflation…

21. April 2023 at 06:51

Commercial bank credit, which shows a contraction, excludes the old thrifts’ credit (in spite of the thrifts being turned into banks by the DIDMCA, i.e., The DIDMCA allowed credit unions and savings and loans to offer checkable deposits).

But paradoxically, the money stock includes the deposits of the old thrifts.

It is the 10-month rate-of-change in our “means-of-payment” money that determines the onset of a recession, that determines R-gDp.

Contrary to Nobel Laureates Dr. Milton Friedman and Dr. Anna Schwartz’s “A Program for Monetary Stability”: the distributed lag effects of monetary flows (using the truistic monetary base, required reserves), have been mathematical constants for > 100 years.

21. April 2023 at 08:02

Randomize, Airfares? (That excludes energy)

22. April 2023 at 07:35

As Dr. Philip George says: “The velocity of money is a function of interest rates”

As Dr. Philip George says. “When interest rates go up, flows into savings and time deposits increase”.

As Dr. Philip George puts it: “Changes in velocity have nothing to do with the speed at which money moves from hand to hand but are entirely the result of movements between demand deposits and other kinds of deposits”.

See: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LTDACBM027NBOG

Dr. Philip George’s “The Riddle of Money Finally Solved” works.

“For nearly a century the progress of macroeconomics has been stalled by a single error, an error so silly that generations to come will scarcely believe that it could have persisted for as long as it has done.” & “The logic was that such precautionary holdings are not intended to be spent and hence do not qualify as money.”

23. April 2023 at 02:26

If private sector participants have a difficult time figuring out what the Fed is doing with the economy, then why should we think that the Fed would be any better off looking to futures market forecasts to make policy judgments? Seems like the blind leading the blind.

Also, I read up on the guardrails idea. Isn’t this concept of the public purse taking on more and more investment risk hiding inherently instabilities? If you sell unlimited contracts guaranteeing <5% NGDP growth, and then make a policy error that leads to overshooting, paying out those contracts can easily feed into a hyperinflationary spiral, no?

23. April 2023 at 07:10

Jeff, You said: “If you sell unlimited contracts guaranteeing <5% NGDP growth, and then make a policy error that leads to overshooting, paying out those contracts can easily feed into a hyperinflationary spiral, no?"

You are missing the point. The whole point is to prevent the Fed from taking on that risk, by telling them they'll be punished if they lose a lot of money. This will push them to avoid a strong net short or net long position. If we'd had this in effect in 2008 and 2021, we would have avoided some major policy mistakes.

24. April 2023 at 23:04

Thank you FutSceptic

Scott,

I have read your seekingalpha article on the guardrails approach and I do not find my questions answered (pls. provide a link to a more extensive paper so that there can be no misunderstanding).

My question is still not answered: from whom is the Fed supposed to buy or sell those futures? Nobody produces NGDP Futures, nobody can use them to hedge microvariables to which they are exposed (exception: government tax collection, however I am not sure this is a rational actor 🙂

I also find your analogy with a pegged FX misplaced:

In a pegged regime, the central bank keeps the medium of exchange and the unit of account in some sort of predictable range, i.e. buying and selling directly affects the purchasing power and economic calculation of everybody in the community -very effective monetary transmission

This is not the case with NGDP futures. Here, if I am correct, buying and selling will only affect a few speculators – u get as much transmission as Bernanke with his “trickle down” policies, maybe even less…

25. April 2023 at 04:25

Viennacapitalist, You asked:

“from whom is the Fed supposed to buy or sell those futures? Nobody produces NGDP Futures,”

The Fed would produce the contracts, and buy and sell with whoever wished to trade with the Fed. If no one wished to buy or sell the contracts, that’s fine. Then the Fed reverts to discretion.

I assure you that I would have sold short in 2008, and bought in late 2021, and made lots of money. I can’t believe I would be the only person doing so.

Under foreign exchange rate targeting, FX transactions only directly affects a few people. Indirectly, the targeted rate affects the entire economy.

26. April 2023 at 04:20

Scott,

so you (and a few others) would have made out like a bandit in 2008 and 2021. Once the contract closes, your wealth would have gone up by the gain on the contract upon settlement. You have made a sucessful speculation. It clearly matters how many successful speculators there are, for monetary transmission (the fact that there are more than you is clearly not a sufficient condition).

Settlement details matter and are unclear to me. To stick with your example:

Your gains in 2008 and 2021 only accrue after the actual NGDP print. Until then you have an open risk position that consumes your risk budget

In 2008 this means that you get a windfall denominated in high powered money, AFTER it has become clear that NGDP falls short of the futures price. Now some speculators (it clearly matters how many of them there are to have a meaningfull impact) get reserves and they can stimulate demand. The fed is on the loosing side of the transaction and has to pay those reserves out of equity. That is fine (albeit limited by equity of the Fed)

In 2021, the it wuould have been the other way. You gain after it has become clear that NGDP is higher than the strike. You get accredited MORE reserves (you are a winner and want to be paid) – this is expansionary!!!

Your gain is the Fed’s loss, the loss reduces the equity, not the reserves at a time when we need less reserves than before –

It is clearly unacceptable that there are more reserves than before after we have NGDP > trend…

whose reserves are getting destroyed to pay you?

this is not clear to me…

26. April 2023 at 14:22

viennacapitalist, I think you are missing the point. In my plan, the NGDP futures market is not a mechanism for moving the money supply; the Fed does that through ordinary OMOs. It’s a method of giving the Fed the right information and the right incentives.

If no one speculates, then that just means the Fed is doing a good job. I have no problem with that outcome.

27. April 2023 at 06:14

@Dr. Sumner

In the post you wrote: “Instead, I favor moving toward a regime where we collapse the monetary policy indicator, instrument and goal into one variable—NGDP futures prices. Ideally, NGDP futures prices would be the policy instrument (the thing we target)”

In a comment you wrote: “In my plan, the NGDP futures market is not a mechanism for moving the money supply; the Fed does that through ordinary OMOs.”

I suspect that one cause of communications gaps is that many of the rest of us are used to a “monetary policy instrument” being a “monetary policy mechanism”.

27. April 2023 at 06:22

Brent, Good point. Unfortunately, the economics profession is rather inconsistent with how it uses these terms (which I discuss in my new book.)

Thus, prior to 2008, OMOs were technically the instrument, but the fed funds rate was often called the policy instrument. In my system, NGDP futures prices would be an instrument in the sense that the fed funds rate used to be an instrument before 2008, but not in the sense that the monetary bases was an instrument before 2008.

Thus you can move the base as needed to hit a fed funds target, or you can move the base as needed to hit a NGDP futures price target. (There are other possible targets, such as exchange rates or even gold prices–as under a gold standard.)

27. April 2023 at 23:26

Scott,

your argument is basically that the NDGP futures price is an unbiased predictor of future NDGDP and thus should be the lode star for monetary policy.

this, as you know, contracticts tons of econometric research on futures prices that shows that futures are no unbiased predictor of the underlying variable.

This holds across all markets sudiet (correct me if wrong) even in well functioning markets, i.e. markets where there is a diversity of buyers and sellers as well as the right incentive (profit/loss, etc.)

In your example there is only one market maker that creates these contracts – the fed. The fed has to pay out the profit to successful speculators from equity (that would ultimately be the taxpayer) – those at the fed setting the futures prices are not betting their own money, nor do they loose their job if the trading desk blows up. They will therefore be very hesitant in adjusting prices to supply/demand, limiting the informational content of the futures thus traded even more…

It is important to recall how complex market microstructure can be.

It is not so straightforward to adjust prices to supply and demand as one might think, i fail to see how the fed trading desk would do that (somebody would have to set the proper incentives, the risk budget, the P&L target, etc.) For, if the fed traders do not have the proper incentives, prices will be comparatively stale and the information content even less…

Then, of course, there is the problem that published NGDP gets revised a lot in the following months/years. You might be correct in your prediction, but the NGDP at settlement date might not fully reflect the effec that you (correctly) predict – this fact alone warrants a risk premium (biased) on the futures price…

PS. really like your new book, thanks for sharing it

28. April 2023 at 05:22

@viennacapitalist –

You wrote: “Scott, your argument is basically that the NDGP futures price is an unbiased predictor of future NDGDP”

My take on Dr. Sumner’s argument is: he argues that the NGDP futures price would likely be a better predictor of future NGDP than any other (feasible) proposal.

28. April 2023 at 07:27

Atlanta Fed’s gDpNow hit R-gDp on the nose @ 1.1%. That’s as good as any future’s market.

28. April 2023 at 07:59

Economists don’t know money from mud pie. The 10-month rate-of-change in short-term money flows, the volume and velocity of money, the proxy for the real-output of goods and services, must turn negative before any recession.

And the demand for money has been falling since April 2008, i.e., its reciprocal, transaction’s velocity, has been rising.

See:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=eTtE

28. April 2023 at 08:30

Viennacapitalist, You said:

“your argument is basically that the NDGP futures price is an unbiased predictor of future NDGDP and thus should be the lode star for monetary policy.

this, as you know, contradicts tons of econometric research on futures prices”

No, my argument is that “tons of econometric evidence” suggests that the risk premium on NGDP futures contracts is likely to be much too small to be of macroeconomic significance. Do you disagree? How big do you think it would be?

“Then, of course, there is the problem that published NGDP gets revised a lot in the following months/years.”

No, that’s not a problem at all, or at least not any more than a policy that targets NGDP without using NGDP futures contracts. I would note that there’s no evidence that the initial NGDP estimate is a biased forecast of future estimates, which is all that matters. A policy that targets the initial estimate is basically identical to a policy that targets the final estimate

I don’t understand your other criticisms. It’s not clear to me exactly what you think might go wrong. Bad monetary policy? Big Fed losses? What is your specific concern?

30. April 2023 at 06:34

2021-01-01 11.7

2021-04-01 13.8

2021-07-01 9.0

2021-10-01 14.3

2022-01-01 6.6

2022-04-01 8.5

2022-07-01 7.7

2022-10-01 6.6

2023-01-01 5.1

N-gDp still above target. But there are some ominous signs. What derails economic expansion is a shifting of demand deposits to gated deposits.

Contrary to the myopic banker, from the standpoint of the system, banks create deposits, they do not lend them. This shifting destroys the velocity of circulation (because all bank-held savings originate within the system). I.e., the banks pay for the deposits that they collectively already own. This results in a consolidation of the banks.

Can you hear the sucking sound?

Small-Denomination Time Deposits: Total (WSMTMNS) | FRED | St. Louis Fed (stlouisfed.org)

Large Time Deposits, All Commercial Banks (LTDACBM027NBOG) | FRED | St. Louis Fed (stlouisfed.org)

Call it the paradox of thrift or precautionary savings. But from an accounting perspective, or flow, bank-held savings, stock, are frozen.

See: “Should Commercial banks accept savings deposits?” Conference on Savings and Residential Financing 1961 Proceedings, United States Savings and loan league, Chicago, 1961, 42, 43. By Dr. Leland James Pritchard, Ph.D., Economics, Chicago 1933, M.S. Statistics, Syracuse.

See: “Profit or Loss from Time Deposit Banking”, Banking and Monetary Studies, Comptroller of the Currency, United States Treasury Department, Irwin, 1963, pp. 369-386

30. April 2023 at 09:33

See: Why America will soon see a wave of bank mergers | The Economist Apr 20th 2023

“When calculating their regulatory capital, banks with less than $700bn in assets typically do not have to mark to market even the securities that they class as “available for sale” and which are meant to be a source of quick cash in an emergency. Those smaller than $250bn are exempted from the strictest liquidity rules, stress tests and failure planning. This light-touch regulatory regime is now being reviewed by domestic and international regulators.”

2. May 2023 at 03:20

Scott,

I know no evidence that stuggests the risk premium should be small. That’s news to me.

In fact, there are hedge fund strategies that exploit the “forward bias” in observed futures prices. Of course, the strategies do not work all the time- as the risk premium is not constant but varies over time – which complicates things further…

My second point relates to market microstructure theory and the conditions that have to be met to have proper price discovery (that’is what u are looking for). With the fed the major/sole market maker of a contract, I am sceptical these requirements are/can be met.

An analogy from the gold standard might help. Many advocates for the gold standard pointed out that, for it to work without friction, it is necessary that everybody should be in a position to redeem notes for gold, not just a limited amount of players at a limited amount of institutions (banks at central banks, or central banks at central banks, etc.). They were advocating as broad a participation as possible, not priviledged access..

It is the same in your case: only one party is the market maker, i.e. issuer and redeemer of NDGDP futures. and given its set up (deep pockets, no considerations for liquidity risk, questionable profit motive) it is likely to remain the only market maker – thereby significantly limiting price discovery as laid out by microstructure theory.

You will get futures prices, but not unbiased ones and likely not incorporating all available information…

2. May 2023 at 06:09

“the drawdown in inventories actually reduced the headline GDP figure by 2.26%,”

Not to be repeated. Short-term money flows have not turned negative.

Money matters. Core inflation peaked at the same time as long-term money flows peaked. I.e., the correlation was synchronous. I.e., the distributed lag effect was, once again, an historical, or mathematical constant.

2021-01-01 1.7

2021-04-01 3.5

2021-07-01 3.9

2021-10-01 4.7

2022-01-01 5.3 peak

2022-04-01 5.0

2022-07-01 4.9

2022-10-01 4.8

2023-01-01 4.7

2. May 2023 at 06:24

Barron’s “The Fed should target nominal GDP instead of inflation itself.”

“https://www.barrons.com/articles/to-control-inflation-the-fed-needs-to-relearn-monetarism-71896494?siteid=yhoof2

2. May 2023 at 06:30

“You will get futures prices, but not unbiased ones and likely not incorporating all available information…”

I still don’t think you understand what I am proposing in the guardrails regime. I am not trying to get futures prices. The prices are set by the Fed at say 3% and 5% growth, and hence they tell you absolutely nothing. I am trying to set up a guardrail to keep the Fed from going way off course, as they did in 2008 and 2021. Your comment is like claiming that the classical gold standard was trying to discover the market price of gold. No, it set the price of gold.

And this regime would be just as open to small traders as was the old gold standard. Futures markets are not perfect, just better than all the available alternatives.

As far as the size of the risk premium, let me give you an example. Suppose the futures market price was 3.3% but the market forecast was 3.0%. That would be an implausibly large risk premium for this sort of asset, and yet even so the bias would be of little macroeconomic significance. I’m not an expert in this area, but those who are tell me that the risk premium in an NGDP futures market would likely be quite small.

In contrast, FOMC committees often have massive bias in their forecasts. So what’s the lesser of evils?

2. May 2023 at 23:21

Scott,

I am not saying the classic gold standard was trying to discover the price of gold. They were trying to discover the real demand for money balances (they never talk about the price, they always talk about supply and demand for FX, notes, etc.)

The (real) price of gold under the gold standard was set by supply and demand (monetary+nonmonetary) for gold. That’s what everybody cared about. The global market set the price of gold in terms of the local unit of account by promising to keep the peg

By operating the peg under certain (often faulty) principles, they actively influenced the real demand for money balances – that is why broad participation is necessary. Get the money demand wrong, by issuing to many or too little money substitutes and you get all kind of nasty results…

I have to admit, I do not understand how this guardrails approach is supposed to function. I had the impression that it was about the information content, i.e. signalling of futures prices which are thought to be superior to Fed Forecasts.

Now, if futures prices are not meant to move there is no info content. we do get, after time, a set of successful NGDP forecasters.

Why not write a blog post, of how the guardrails approach wuould have worked in 2021? Better: write how it would function right now, i.e. a live excercise?

I can immagine many of your readers would be interested in that…

4. May 2023 at 13:20

Here’s how it would have worked in 2021. Lots of people, including me, would have gone long on NGDP futures in late 2021. The Fed would have seen the risk of losing a lots of money, and tightened monetary policy. That’s good!

If they didn’t tighten monetary policy, then I would have gotten very rich. That’s also good!

4. May 2023 at 22:42

Scott,

“…The Fed would have seen the risk of losing a lots of money, and tightened monetary policy. That’s good!…”

would the Fed react in time? – they decide these tings in committees, after all…

“…risk of loosing money..”

what is the Fed’s reaction function? What is its risk tolerance? Is the risk tolerance, i.e. the willingness to sustain losses a function of the election cycle (you bet it is)?

What does loosing money mean anyway to the Fed? And by what amount should they tighten? Until someone stops buying NGDP futures?

These things determine the point and amount of tightening and are NOT straightforward. I am afraid you would get the same delayed reaction function that you have now…

As per your last sentence: that’s “trickle down economics” and doesn’t work as you know, although I would be happy for you as an individual 🙂

5. May 2023 at 17:23

Hi Scott,

Do you think those maniacal imbeciles in Congress will raise the debt ceiling? I know they did it 11 years ago, but right wing lunatics in Congress have only gotten more

Prevalent: I heard an extended default (for a quarter) could cost the US 8 million jobs. How would the Fed offset this?

Your thoughts?

Edward

6. May 2023 at 00:30

The Fed would offset it by injecting more liquidity into the market, and artificially lowering rates below their natural rate, which is what they did for a decade. Look, the government is not the answer to any problem; it is the problem. From 1920 to 1929 the Fed kept interests rates lower than the natural rate, and we all know what happened. continuing to bailout these banks by subsidizing their risk with blue collar tax payer money is so immoral that anyone who continues to propose is must have some totalitarian agenda; such policies will continue to make the bubble bigger until one day the correction is so massive that some generation is left indebted beyond imagination. Sumner’s generation was the catalyst for leaving the gold standard, and all we got from that were massive bubbles, inequality, and lower real incomes.

The bubble has already led to tremendous waste of capital, just look at Twitter. The company employed 10,000 people and lost 4M dollars a day before Musk took over. Despite losing 4M a day, and never making a profit, workers received free lattes and sushi whenever they wanted; the expenses per person were over $300 a day according to his calculations. That’s a massive, massive, waste of capital.

But this isn’t a U.S. problem, it’s a global problem. The liquidity being dumped into the market lowers the value of currencies, and fattens the pockets of the oligarchies. They use it first, then when it gets to you (Cantillon effect) you can’t buy a coke because it costs a hundreds bucks. Essentially, they stealing your money in the form of lower real incomes over a long period of time.

This is why money must be backed to something; either it’s backed to a commodity like Gold, or we agree to use a fixed supply of digital currency like BTC. The fifty year experiment of fiat has failed miserably.