Reason magazine on NGDPLT

I love Reason magazine, but macroeconomics is not their strong suit. They recently published a critique of NGDPLT by Tom Clougherty:

Moreover, even if one accepts that a central bank is capable of hitting its growth target, that leaves open the question as to what target it should aim for. And it is not possible to know in advance what the “correct” rate of NGDP growth should be. The central bank can base its target on past growth, but even educated guesses can’t ultimately overcome this “knowledge problem.”

As London-based economist Anthony J. Evans has pointed out, if you consider 1997, the year that Bank of England began targeting inflation as your base year, and assume a 5 percent annual NGDP growth target, then you would believe that British monetary policy in the run up to the crash was more-or-less fine: NGDP growth stayed close to 5 percent throughout the “great moderation.” You would also believe that we are now significantly below the “correct” level of NGDP, and should fire up the printing presses to bring things up to scratch. If, on the other hand, you assume a 4.5 percent target since 1997, you would think that monetary policy was too expansionary in the run up to the crash, and that NGDP growth has already returned to trend””hence, time for monetary policy to “normalize”. The point here is not that 5 percent is the wrong target, or that 4.5 percent is the right one. The point is that even a small targeting error can have massive policy implications.

This criticism sounds plausible, but on closer inspection it doesn’t make any sense. In fact, either 5% or 4.5% NGDP targeting since 1997 would have been fine. What the author misses is that under either target path the volatility of NGDP would have been much lower, especially after 2007. Consider the 4.5% path. It’s true that this path would imply that monetary policy is currently right on target. What Clougherty misses is that a 4.5% NGDP path after 1997 would have resulted in far smaller gains in NGDP in the lead up to the Great Recession. About 5% less, to be specific. And this means that nominal hourly wages in Britain would also have been about 5% lower then they actually were. And since nominal wages are sticky, wage levels today would also be far lower. So the same nominal income that produces 7.8% unemployment in Britain today, might lead to only 5% or 6% unemployment if nominal hourly wages were much lower.

The easiest way to think about business cycles is to look at the interaction between changes in NGDP and changes in nominal hourly wages. When NGDP falls and wages are sticky then there will be less hours worked. You won’t see that in DSGE models, but that’s what’s actually going on. Reducing NGDP is like taking a couple chairs away in a game of musical chairs. Several participants will end up sitting on the floor. If you want to solve that problem you add chairs to the game. And if people are unemployed because of the downward stickiness of nominal wages, then you add NGDP to restore full employment.

If people are unemployed because of structural rigidities, then more NGDP probably won’t help (unless that made it more politically feasible to remove structural rigidities like extended UI benefits.)

Evan Soltas allowed me to quote from a recent email he sent out:

I am glad to see NGDPLT getting some play in the libertarian discussion, but there’s quite a bit to criticize about this piece.

(1) I do not understand the argument that macroeconomic stability would prevent sectoral rebalancing. It is a common argument, but I don’t think it withstands serious scrutiny. Macroeconomic instability ought to make sectoral rebalancing more costly.

(2) The author is wrong to suggest that an NGDP target will mean easier credit. Again, a disturbingly common argument.

(3) A “de-facto” NGDP target fails to capture one of the most important benefits — having a clear path for expectations. Many of us have written, more or less angrily, about the Bank of England because of its failure in this respect.

(4) There’s no such thing as the “correct” NGDP target. There might be a welfare maximizing trend rate of NGDP, but within a range of 3 to 6 percent, the welfare costs from missing the optimum will not be significant. I fail to see a knowledge problem. I think the author is butchering Hayek here.

(5) The paragraph recounting Anthony Evans’ argument makes no sense. So what if the extrapolated 10-year trend between 5 and 4.5 percent would capture NGDP? Deciding after the fact that you’re going to drop down onto the previous trend is the source of the problem, not anything about a small targeting error.

Tyler Cowen recently noted that Greece has had surprisingly high inflation for a country mired in a deep depression. I agree that this is a deep embarrassment for New Keynesian models. On the other hand NGDP in Greece has fallen sharply, so we market monetarists are not at all surprised by their high unemployment rate.

PS. Tyler asked the following:

Scott Sumner has a view which I do not understand, and thus do not wish to try to state, but it has something to do with not really believing in the concept of price inflation.

A few remarks:

1. Economists often discuss whether the CPI measures inflation accurately. But how can that discussion mean anything when economists have never even explained what the term ‘inflation’ means in an economy where product quality changes rapidly, and where new products are constantly introduced. Is it the amount of extra income one needs to maintain constant utility? If so, then we need to define utility. And suppose happiness surveys show no increase in happiness over 50 years. Would that mean RGDP did not rise?

2. There are many types of price indices—it’s not at all clear which one is the “right one.” I used to do lots of posts talking about how the government claimed housing prices rose 8% after 2006 and Case-Shiller said they fell 35%. Can they both be right? Sure, because inflation is a vague and poorly undefined concept, so any measure is fair game.

3. If you have what looks like a demand-side recession (a deep fall in NGDP) and are puzzled that inflation has not fallen as much as you think it should have, then you should first examine the stickiness of hourly nominal wages. If they didn’t fall, then sticky wages is your explanation. If they did fall sharply, then some other factor explains the stickiness of inflation. This might be higher VAT taxes, higher import prices, or some other sort of adverse “supply shock.”

4. If you have an adverse supply shock, then inflation should rise. If inflation falls despite an adverse supply shock, then you have both an adverse supply shock and an adverse demand shock. Both would be contributing to higher unemployment.

5. When I was researching neoliberalism back in 2007 I found that Greece had the least market-oriented economy in the entire data set (of 32 countries.) If the government is running much of the economy, various government policies may introduce a degree of price stickiness. Tim Duy has a post that discusses one example. And Tyler responds. I think Tyler’s right about the unreliability of Phillips Curve models, but I’d make the following observation, FWIW:

Tim’s graph shows inflation falling from about 3% to 4% before the recession to about minus 1% today. In the Great Depression in America inflation fell slightly more than twice as much, from zero to minus 10%. Does that difference surprise me? No, America in the early 1930s was far more market-oriented than Greece. I’m not surprised that a monetary shock in Greece that was much smaller than in America can produce Great Depression levels of unemployment in Greece. BTW, interwar price indices were much more weighted toward flexible price goods like food and manufactured goods—not services.

There are many other problems with inflation. The bottom line is that it’s not a well-defined variable, and there is no reason to expect it to be a good indicator of demand conditions in an economy. For that you need NGDP.

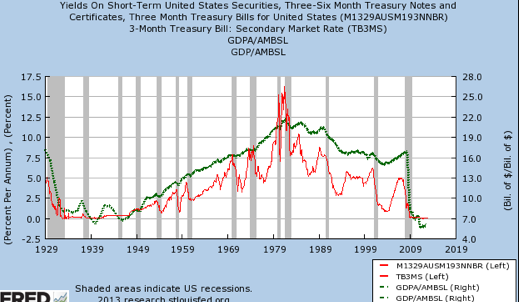

PPS. Earlier I posted on the relationship between interest rates and velocity. Michael Darda sent me a better graph:

Tags:

21. January 2013 at 10:19

Yikes! Is Greece an example of collapsing real growth and rapid inflation? Sure sounds to me that that could be problematic for market monetarist arguments…..

21. January 2013 at 10:22

TravisV, No it’s not, because market monetarists don’t think inflation is a reliable guide to AD shocks, so it actually supports our argument. BTW, Greece’s inflation rate has plunged sharply, as I said in the post.

21. January 2013 at 10:28

This is a bit of a tangent, but whenever I say “I love [X] magazine [or website or blog], but [insert_my_expertise_here] is not their strong suit,” it makes me nervous, because I realize that if they’re getting the stuff I’m expert in wrong, why am I assuming that they’re getting the stuff I know little about right?

This seems to happen to me all the time though–maybe I’m just paranoid.

21. January 2013 at 10:41

My apologies, Prof. Sumner.

21. January 2013 at 10:58

I think the knowledge problem criticism is better stated like this:

From where does the knowledge arise that a constant NGDP growth is better than a (non-constant) NGDP growth rate that fluctuates in accordance with world market supply and demand dynamics?

Tom Clougherty didn’t really make a strong case the way he said it, because he got sidetracked by the particular percentages, but the intuition he seems to be getting at is this:

How do NGDP targeting monetarists know that a perpetual, no ifs ands or buts constant NGDP growth rate is “right”, whereas fluctuating NGDP growth rates are “wrong”?

I don’t think it’s enough to simply point to overall unemployment rates, because to me employment is a means to an end, not an end in itself. After all, if NGDP targeting theorists want to use the rate of unemployment as justification for wanting to keep NGDP growth constant, then let’s stop pretending and just say that the Fed should finance all labor, to simply do “work” at the Fed’s behest.

If the response to this is “No, the goal is not just any employment, but rather a minimum rate AND “correct” employment, then that requires an introduction of concepts within aggregates, not just aggregates. We thus have to consider the possibility that constant NGDP growth, while encouraging overall “employment”, might actually end up discouraging “correct” employment, because in the movement towards overall increases in employment, the lack of fluctuating NGDP is preventing “correct” employment.

If changes to tastes, ideas, technology, and capital are optimally integrated into the market via spending changes industry to industry, i.e. fluctuating industry NGDPs, then why wouldn’t world changes to tastes, ideas, technology, and capital be optimally integrated into the world market via spending changes country to country, monetary region to monetary region?

I don’t see how to get from “Geoff’s nominal income can fluctuate according to his productivity vis a vis other people’s productivity” to “Aggregate country incomes cannot fluctuate according to country productivity vis a vis other country’s productivity.”

Can someone explain where exactly the shift takes place from “Incomes can fluctuate” to “Incomes cannot fluctuate”? I start with myself, and then keep adding people, one at a time, and I see no reason to EVER suddenly change my reasoning and say “OK, NOW the relevant income cannot fluctuate.”

If my income and your income can fluctuate, why not everyone’s?

21. January 2013 at 11:00

Sorry, I missed a quote mark:

If the response to this is “No, the goal is not just any employment, but rather a minimum rate AND “correct” employment<.b", then that requires…

21. January 2013 at 11:07

For a small open economy, import prices will play a large role in the CPI or CEP. With a fixed exchange rate, why would they drop much? In the limit, what “should” happen is that the price level remains unchanged, wages fall, producing exports becomes more profitable, and output and employment recover. The only impact on prices should be for nontraded goods. If tourism is a major export, I am not sure how significant those would be.

21. January 2013 at 11:17

Bill:

OK, now how about the real world, which by the way is not at any “limit”?

21. January 2013 at 11:35

Geoff:

Greece imports add up to more than 30% of GDP. And import prices in Greece have risen twice as fast as the CPI from 2008 to 2012. This certainly fits with Mr. Woolsey’s story.

21. January 2013 at 11:37

Pardinus, I had the exact same thought when I wrote that post. I sometimes say the same thing about The Economist, and The New York Review of Books–which are the other two publications that I subscribe to.

Travis, No worries.

Geoff, I doubt NGDP targeting is always optimal, but I think it’s superior to inflaito ntargeting.

Bill, Very good point.

21. January 2013 at 12:45

Geoff –

“I don’t see how to get from “Geoff’s nominal income can fluctuate according to his productivity vis a vis other people’s productivity” to “Aggregate country incomes cannot fluctuate according to country productivity vis a vis other country’s productivity.””

There is an important difference – different countries use different currencies. Unless they are in a currency union. So aggregates can fluctuate by changing exchange rates.

If you issued Geoff coupons and I issued NOI coupons redeemable for services from you and me repectively, we could each keep our nominal income constant(in Geoff or NOI units) if we chose. The exchange rate of our coupons would fluctuate according to our relative productivity. So our real income would still be determined by productivity.

It’s the same for currency areas. All the money issuer can do is control some nominal variable. Whether it controls the nominal price of gold, a price index or GDP of the currency area, in the long run real GDP will be determined by productivity. So the question becomes, what nominal variable is best for the money issuer to choose? I’d say the GDP over the currency area. Then every price is simply one share of total output of the economy. Second best would be a very broad price index of the whole economy. Worst would be the nominal price of one useless object, like gold.

An important point to remember is the government must make some decision about what it will use for money. NGDPLT is not more government involvement in the economy than any other monetary system. In fact, it is less than most, because it doesn’t affect relative prices, and doesn’t involve discretion and tinkering.

So, Geoff, what do you think the government should use for money to collect taxes, pay employees, etc.? If you have a better idea than NGDPLT over the currency area then I’m all ears.

21. January 2013 at 13:51

Wow this post makes some great arguments. Bravo.

o those who disagree, if we really reached peak natural resources (peak oil, peak copper, peak food production etc.) wouldn’t it be best that prices rise?

21. January 2013 at 16:02

“If so, then we need to define utility.” And, having defined it, we need to *measure* it. The latter, I think, will be the sticking point (for working with ‘inflation’ defined in terms of utility).

“And suppose happiness surveys show no increase in happiness over 50 years. Would that mean RGDP did not rise?” Only if we define ‘utility’ as *what happiness surveys measure*, which, I think, would be a very bad idea.

21. January 2013 at 17:12

Laurent:

“Greece imports add up to more than 30% of GDP. And import prices in Greece have risen twice as fast as the CPI from 2008 to 2012. This certainly fits with Mr. Woolsey’s story.”

Unchanged price level, and falling wages?

21. January 2013 at 17:12

Negation of Ideology:

“There is an important difference – different countries use different currencies. Unless they are in a currency union. So aggregates can fluctuate by changing exchange rates.”

“If you issued Geoff coupons and I issued NOI coupons redeemable for services from you and me repectively, we could each keep our nominal income constant(in Geoff or NOI units) if we chose. The exchange rate of our coupons would fluctuate according to our relative productivity. So our real income would still be determined by productivity.”

In that scenario, neither of us would ever go nominally bankrupt no matter what we did. How would a fluctuating exchange rate between Geoff coupons and NOI coupons be sufficient to giving us an incentive to producing optimally?

“It’s the same for currency areas. All the money issuer can do is control some nominal variable. Whether it controls the nominal price of gold, a price index or GDP of the currency area, in the long run real GDP will be determined by productivity. So the question becomes, what nominal variable is best for the money issuer to choose? I’d say the GDP over the currency area. Then every price is simply one share of total output of the economy. Second best would be a very broad price index of the whole economy. Worst would be the nominal price of one useless object, like gold.”

Well, I think that once you grant the presence of a monopoly money issuer over a certain territory, then you have immediately included a requirement for some sort of “rule”, since by definition there are no market forces that would bankrupt the money issuer itself.

If that is the context, and we ask which rule(s) is(are) best, then the ultimate justification is purely one of personal preference, because any personal preference would not be subject to any market-based competition from other preferences.

If you prefer total spending be targeted, and I prefer that total spending be targeted with the additional proviso that I am either the sole money issuer or sole primary dealer, then because neither of our preferences can compete in any market setting, it follows that there is no “correct” nominal statistic to target, if by “correct” we mean based on individual reason. But if by “correct” we mean based on power, i.e. governmental law, then he whose preference is being enforced by law, is “correct”.

“An important point to remember is the government must make some decision about what it will use for money. NGDPLT is not more government involvement in the economy than any other monetary system. In fact, it is less than most, because it doesn’t affect relative prices, and doesn’t involve discretion and tinkering.”

Dude, ANY money creation from a monopoly issuer of money, whereby the money issuer does not add to EVERYONE’S money (checking) accounts, but only some people’s bank accounts, after which these people then spend that money on only some others, and those others spend money on only some others, and so on, there WILL be a change to relative spending and prices, guaranteed.

Also, of course there is discretion. The money issuer has to decide what to buy, who to buy it from, when to buy it, and how frequently total spending is to be measured and targeted. There is discretion all over the place. Just because you propose 5% NGDP growth, it doesn’t mean it isn’t discretionary. It would be as discretionary as 2% price inflation targeting.

“So, Geoff, what do you think the government should use for money to collect taxes, pay employees, etc.? If you have a better idea than NGDPLT over the currency area then I’m all ears.”

The optimal system is myself being the sole money issuer.

The second best system is someone else being the sole money issuer, but I am the sole primary dealer.

The third best system would include another primary dealer along with me. Then adding primary dealers one at a time, until we get to:

The nth best system would be where everyone who is not the sole money issuer is a “primary dealer” themselves, which means the money issuer would buy assets from everyone in exchange for equal sums of money.

As for which specific rule the money issuer should abide by, and I am not the money issuer, then I can only go by personal preference, and my personal preference in this context would be for the money issuer to target my personal income to grow by whatever is required in order to bring about your personally preferred rule, which is NGDPLT. If that means the central bank has to make me a multi-billionaire, or trillionaire, in order to ensure that I spend enough on others who then spend enough on others after that, such that your NGDPLT is achieved, then I guess I will take one for the team and capitulate to NGDPLT.

Now, given that you would probably reject my preference, for obvious reasons, there is nothing else we can say to each other, because we aren’t even in a debate that can be settled rationally, through respect of personal property anyway. This debate can only be settled irrationally, through disrespect of personal property via the hammer of a non-market law. Your rule wins by the force of law, then it’s settled. If my rule wins by the force of law, then it’s settled.

21. January 2013 at 17:22

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, I doubt NGDP targeting is always optimal, but I think it’s superior to inflaito ntargeting.”

I am inclined to agree. But does one step better mean “good”? One step better can still mean terrible.

What other rules can be, potentially, more optimal than NGDP targeting?

In a world market context, maybe some sort of currency area productivity competition rule would be better than constant growth NGDP rule. Maybe if a country produces less, and imports more relative to exporting, then that country should have a reduced quantity of money and volume of spending, and vice versa.

It’s very similar to how a household, or firm, or industry, experiences changes to nominal demand, when they produce more or less relative to other households, or firms, or industries.

If one individual reducing their productivity results in a reduction to their money and income, then why shouldn’t the same thing happen to more than one person, say a country’s worth of people?

I am imagining Greece, and how falling money and spending is justified there considering how many bad decisions were made. I don’t think it makes any sense for the ECB or whoever to print up enough new money to prevent nominal bankruptcies there. Let em go bankrupt so they change their ways. Just like we say bad workers and bad managers should go bankrupt, rather than be bailed out.

Does it make any sense to prevent recessions in all currency areas, no matter how bad decisions get?

I am imagining a horror future whereby currency area populations become numbed down, apathetic, irresponsible, and gradually more and more unproductive, because no matter what anyone did, a diversified currency area portfolio would never incur nominal losses. This is because NGDP would never fall, and NGDP divided by capital is a proxy for the rate of return on a diversified portfolio in that currency area.

I don’t think it’s right to say that groups of people can never make mistakes and never make bad decisions, but that’s what NGDP targeting seems to presume. Even if 99% of a currency area population reduced their productivity, they would not incur any nominal losses in their diversified portfolio. I think that would be bad news.

21. January 2013 at 17:29

“I don’t see how to get from “Geoff’s nominal income can fluctuate according to his productivity vis a vis other people’s productivity” to “Aggregate country incomes cannot fluctuate according to country productivity vis a vis other country’s productivity.””

Isn’t it more accurate to say that Geoff’s *real* income will fluctuate according to his productivity vis-a-vis other people’s productivity? Similarly, aggregate country real incomes (GDP) will fluctuate according to country productivity. Both of these will happen whether or not the central bank is doing NGDP level targeting.

The question is whether a steep decline from NGDP trend path will drive country productivity (real GDP) down.

21. January 2013 at 17:31

Concerning Soltas’ (1). One of the argument for NGDPLT (as I understand it) is that during a supply shock, the Fed will adopt an expansionary policy with an unexpected rise in inflation. When it does so, is the Fed not simply “tricking” workers into accepting high nominal wages that are lower in real terms? I think Lucas made this argument against Keynesian stimulus. If one assumes that workers face a lower transaction cost when bidding for their previously held employment than for a new one, does this not slow down rebalancing?

21. January 2013 at 18:48

“Economists often discuss whether the CPI measures inflation accurately. But how can that discussion mean anything when economists have never even explained what the term ‘inflation’ means in an economy where product quality changes rapidly, and where new products are constantly introduced.”–

excellent blogging, and I love the above paragraph.

Add on: “Quick migration of consumers and business to the rapidly evolving best products and services, and retail formats makes constructing a CPI index a craft, not a science.”

Anybody economist think about Craigslist, btw? By wiping out the transaction cost of a classified ad, and four color pics, wow–a retail environment for any used product, and many new ones, is created.

99 cent stores? I buy for 99 cents what I used pay a couple of bucks for…in the 1980s. I even have bought reading glasses. For a buck.

Digital pictures and global transmission thereof?

Instant delivery of PDFs (remember crosstown delivery services and Fedex?).

Downloading 60 detective novels from Amazon, for $1? Many others are free!

And pollution? I won’t even go there, suffice it to say that Forbes recently reported that emissions from vehicles have been cut 98 percent in Los Angeles in the last 40 years….skies are blue, even in summer, see the San Gabriels…

But let’s fixate on the CPI!!!!! Price stability!!!!!!

21. January 2013 at 18:51

I forgot to mention universal product and service differentiation.

Sure, I can compare a banana to banana, but other than some farm commodities, I cannot think of a good or service I purchased that can be strictly compared to another like product or service….

21. January 2013 at 20:03

F. Lynx Pardinus:

Michael Crichton called it the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect:

Full speech text is here.

21. January 2013 at 21:49

And now we know where MF went…

Thank God for Evan Soltas. You’re a legend, mate.

Ben, yes, what Great Stagnation?

P.S. “Inflation” is exactly what the GDP deflator measures, and it is linked to marginal utility, not total utility (Hence GDP is better at measuring changes in welfare than total welfare). The CPI and PCE are for compensating retirees (and other investors) and appeasing the public. (But obviously housing prices fell, and rental prices roses, that’s a manufactured confusion there).

21. January 2013 at 22:04

economists have never even explained what the term ‘inflation’ means in an economy where product quality changes rapidly, and where new products are constantly introduced.

Doesn’t that criticism apply to “GDP” too? Is $1 spent blowing up people in Pakistan the same as $1 spent at In-N-Out? Why is $1 spent for a meddlesome bureaucrat counted but not $1,000 I spent buying used furniture off Craigslist? Can $1 spent in 1960 be usefully compared in GDP to $1 spent 50 years later?

Both inflation and GDP are aggregate measures resting on generalized assumptions, but only inflation is flawed in a material way? (it may be, I really am just asking).

21. January 2013 at 22:11

OK Scott, you *must* take a look at these two: The Economist on the history and future of macroeconomics:

http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2013/01/brief-history-macro

http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21569752-efforts-are-under-way-improve-macroeconomic-models-new-model-army

21. January 2013 at 22:14

Bababooey, both GDP and the GDP deflator are great accounting measures, informative about welfare to a limited extent when interpreted intelligently (not reported without interpretation as the newsmedia does, preferring instead to spend their economist-hiring money on dumb stock-market commentary). But the PCE is simply the wrong measure for the purpose which it is used by central banks. We should switch to NGDP targeting.

21. January 2013 at 22:48

If people are unemployed because of *disequilibrium induced* structural rigidities *caused by prior money & finance disequilibrium creating systematic discoordination of prices and production plans across time*, then more NGDP probably won’t help.

21. January 2013 at 22:57

Scott writes, “Is it the amount of extra income one needs to maintain constant utility? If so, then we need to define utility.”

Lord, no!

22. January 2013 at 02:35

Living in Portugal, I have given some thought to this question (data for .pt is very similar to that of .gr).

Many things do feel cheaper, but it does not show up on the data.

My working theory is that many businesses have responded not by lowering prices on the same products, but by offering or emphacising lower-priced alternatives. So, lunch is cheaper than it was a year ago, but you are now getting lighter fare (more chicken, less beef).

On other things, it’s actually sort of annoying. The other day I had to talk a salesperson into showing me the expensive alternative to the pan they had showed me because I thought the cheap one seemed shabbily finished.

(This is all anecdotal, I have no data.)

22. January 2013 at 02:36

Whilst Rome burns…: http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/01/21/us-eu-transactionstax-idUSBRE90K0WX20130121

22. January 2013 at 04:55

Michael:

“Isn’t it more accurate to say that Geoff’s *real* income will fluctuate according to his productivity vis-a-vis other people’s productivity? Similarly, aggregate country real incomes (GDP) will fluctuate according to country productivity. Both of these will happen whether or not the central bank is doing NGDP level targeting.”

I wouldn’t say it’s more accurate, but I agree with that. Yes, real income will fluctuate, but nominal income won’t, and so there is less of an incentive to change course.

How much harder or less harder do you work due to the fact that your real income changes year to year? Most people go by nominal incomes, which is why nominal wages, not real wages, are sticky.

“The question is whether a steep decline from NGDP trend path will drive country productivity (real GDP) down.”

Probably downwards, if you don’t distinguish between “employment and output” and “correct employment and correct output.”

22. January 2013 at 05:09

Be bolder. What’s the economic justification for targeting one particular definition of inflation in preference to another?

Isn’t any choice of measure subject to measurement problems (substitution, imputation, hedonic correction, technologic and demographic change, etc.)?

Won’t the use of any particular measure produce economic distortions in some circumstances?

22. January 2013 at 05:27

Explanation of Greek “inflation”:

1) VAT increase forced by the IMF pushed up prices.

2) Import dependent economy, many prices at EU levels – imported inflation

3) Cost push inflation from increase in taxes, fixed other cost and decreased sales.

4) Measurement problems. Huge underground economy escapes measurement. Prices are measured on a smaller part to true total GDP. Some posted prices may be high, but fewer people are paying them.

5) As with the US, there are a number of possible inflation

measures. These don’t agree.

These are all true, but the relative contributions of them aren’t clear.

22. January 2013 at 06:45

Greg,

Because there are no definitions of utility that even make sense, we are getting barraged with commercials on a daily basis where one kid tells kids a few years younger, “Your generation has it made” just because the TV can now be moved around the house or yard.

22. January 2013 at 06:56

Central banks should not really be targeting a cost of living index in which utility considerations matter anyway; they do so partly for political reasons (ie the punters want the cb to stop the prices of what they want to buy from rising) and partly for availability reasons (ie that is what government statisticians construct). Ideally, what central banks should target is some kind of weighted (by value of transactions) transaction price index (ie something like P bar in the equation of exchange), because the aim of the central bank should be to provide enough money to facilitate transactions but not so much or so little as to raise or lower P bar. And such an inflation measure is less philosophical.

22. January 2013 at 07:22

RebelEconomist,

i dunno…pehaps you are right about cb and utility. However, progress in the present depends on expanding technological utility to those who actually need and would buy it, were technology actually freed to create it today in housing and all forms of construction and building in general. We live in a Luddite world, one that too few want to change because it tries to pay for needed services that keep expanding anyway. That is the problem: too many people pretend the present technology is perfectly sufficient for progress just because it has provided some sort of entertainment paradise.

22. January 2013 at 08:26

Becky,

Suppose that if you wanted a new car, you could just go out to your front yard in the spring and plant a car seed. Come October, you’d pick it, gas it and drive away. What would happen?

1) There would be a torrent of IP claims on auto seeds attempting to extract rents from those who couldn’t afford to fight the claims.

2) There would be zoning restrictions on where you could plant car seeds and licensing restrictions on who could plant and harvest.

3) Only authorized approved seeds could be planted bought from licensed dealers. These seeds would be taxed.

4) Growers would have to pass courses in responsible automobile growing to maintain quality standards (when to water, don’t plant to close together, proper fertilizer….).

In short, anyone and everyone who had any chance of extracting rent would jump at it, and your representatives would help them.

In my father’s day, calling someone an air inspector was a joke.

22. January 2013 at 08:36

Geoff, Nominal wage rate targeting might be best.

Phillippe, No, it’s tricking them into accepting the wage they’d prefer if they didn’t have money illusion.

Ben, Good points.

Jim, Excellent comment.

Saturos, Do you mean exactly what the GDP deflator measures, or what it would measure if it did things the way that you preferred?

Bababooey, Yes, if inflation is mismeasured, so is RGDP.

Peter, Thanks for the informative list of measurement problems in Greece.

Rebeleconomist, That would be a unmitigated disaster, as 99% of transactions are not for goods or services.

22. January 2013 at 09:01

Peter N,

“…and your representatives would help them.” I know, which is why it’s difficult for me to identify with any specific representatives, who still have no structural, measurement-based means to see actual potential perimeters within a given whole.

22. January 2013 at 09:17

Scott,

Tim Duy has a recent post on Greece where he factors out the price of energy and shows year on year deflation starting in September. He provides supporting articles to show that the source of the rise in energy prices in Greece is increased excise taxes on energy.

But it’s not just taxes on energy. Greece raised the VAT tax from 19% in 2009 to 23% in 2010:

Page 98:

“…In February 2010 a generalised increase in VAT rates was approved, with the standard rate raised by two points to 21 % and the reduced rate increased from 9 % to 10 %. A further increase brought the standard and the reduced rate to 23 and 11 %, respectively, since July 2010. With effect from 1st January 2011, the reduced rate was increased to 13 %, whereas the super-reduced rate was raised to 6.5 % and its applicability extended to hotel accommodation services. Excise duties on cigarettes, alcohol and fuel, as well, have been increased repeatedly. Other new measures introduced in 2011 include the move of some non-basic goods and services from the reduced to the standard VAT rate, and a special real estate duty on residential property, calculated on the surface area of buildings, taking into account also its age and location. The duty is collected through payment of electricity bills (52).”

Page 99:

“VAT rates have been subject to generalised increases in the course of 2010 (see above). The standard rate is 23 % (up from 19 % in 2009). The reduced rate – applicable to goods such as fresh food products, some pharmaceuticals, transportation and electricity, as well as to certain professional services, and (non-exempt) services by doctors and dentists – was raised to 13 % from January 2011 (up from 9 % in 2009). A 6.5 % rate (previously 4.5 and then 5.5 %) applies to hotel accommodation services, newspapers, periodicals and books. For the region of the Dodecanese, the Cyclades and Eastern Aegean islands the above rates are reduced by 30 %. In addition to VAT, excise duties are levied on mineral oils, gasoline, tobacco, alcohol, beer and wine. Excises on electricity – with the exception of that produced by renewable resources – were introduced in early 2010.”

http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/resources/documents/taxation/gen_info/economic_analysis/tax_structures/2012/report.pdf

There’s a way to factor out taxes from the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) in Eurostat. It’s called HICP at Constant Taxes. When you compare it to standard HICP:

you’ll find a big wedge opened up between the two indicies (nearly 5%) between June 2009 and July 2010. And whereas the HICP excluding energy showed year on year deflation starting in September, the HICP at constant taxes first showed year on year deflation in February 2011.

And of course energy (and food) prices did increase in 2010 and 2011 apart from that, but there’s no way that I know of to exclude both energy prices and taxes without double counting.

22. January 2013 at 09:19

The impact of VAT taxes on eurozone monetary policy is an issue that is more or less totally ignored. Of the 17 eurozone members, nine have raised their VAT rates since 2008 (Page 28):

http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/resources/documents/taxation/gen_info/economic_analysis/tax_structures/2012/report.pdf

This includes every single one of the GIIPS.

The ECB Governing Council has encouraged eurozone members to raise taxes, particularly VAT taxes, as a way of dealing with the sovereign debt crisis. But this has artificially raised the eurozone inflation rate.

For example when the ECB raised the policy rate in April 2011 (which was followed by another increase in June) the year on year (March) eurozone HICP was 2.7%, but the year on year HICP at Constant Taxes (February) was only 2.0%.

Of course, by raising the policy rate, this made the sovereign debt crisis even worse, which led to another round of VAT tax increases, which in turn led to another increase in the inflation rate. And so fiscal austerity leads to monetary austerity which leads to more fiscal austerity etc. This is the absurdity of Euroausterity torture device in action.

22. January 2013 at 09:31

Mark, Thanks for all that info on the VAT. Very useful. Yes, it’s a torture machine.

And I linked to Tim Duy’s post in this post, as I’m sure you noticed. 🙂

22. January 2013 at 10:15

Unexepectedly high Greek inlation? 0.8% to 2%… that doesn’t surprise me one bit. The price of yogurt in Greece cannot be that much lower than the price of yogurt in France. If it were more than a few cents a conainer, then some clever soul would ship yogurt from Greece to France. For many goods, the rate of inflation should be uniform. Services, however, may not be so easy to export. There may be some deflation in Greece there. Wages, which are not CPI, I would expect substantial deflation.

Is anything going on that is inconsistant with what I have outlined here?

22. January 2013 at 13:06

Doug,

One thing is there’s been a reluctance to cut government pensions.

For this and much else on Greece see:

http://www.greekdefaultwatch.com/

22. January 2013 at 14:32

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, Nominal wage rate targeting might be best.”

Thanks! That’s an interesting idea. But then I ask myself why that is. Is it because I would stand to benefit as a wage earner? If so, then what about non-wage income earning people, for example those who pay wages? From their perspective, the Fed would be setting a cost floor. Is that not similar to the minimum wage laws we have now? For even if employers tried to pay less wages, they couldn’t, because the Fed would simply inflate more and reverse it.

Can I ask why you think nominal wage rate targeting is better than NGDP? Is it because you think that at the end of the day, after all is said and done, it is the wage earners’ interests that should be catered to? I don’t mean to be rude, but what is so special about wage earners that makes their interests the most important?

22. January 2013 at 16:32

Wouldn’t you say the tips-note spread is the inflation rate?

22. January 2013 at 18:32

Scott, If macroeconomics is all about nominal GDP and “sticky wages” why is it that the business cycle is much more volatile in early-stage capital goods and durable goods industries? It seems like excessive NGDP growth, even if that growth is stable and continues to hit level targets over time, could still lead to cumulative imbalances of the Hayekian sort. Hayek believed, from what I understand, in a nominal spending stabilization norm for ideal monetary “policy”. But he also appreciated how credit conditions had a significant impact on the structure of production and thus the composition of both physical capital and human capital. How do you relate your model to these capital structure issues? What about the fact that NGDP doesn’t actually account for all nominal spending, such as intermediate goods or assets? If the idea is to stability MV or PT, why should we consider the current definition of NGDP to be a good representation of that concept?

Isn’t it possible that Hayekian criticism of excessive NGDP growth in the 2000s lead to unsustainable structural changes whose unwinding made the Fed’s challenges more difficult? The Bear Stearns collapse happened in mid March 2008. Up to that point, NGDP growth was on trend, right? I understand that financial market conditions were weakening starting in 2007, even though NGDP was chugging along. Moreover, growth went negative in December of 2007, even though NGDP was chugging along. Couldn’t it be the case that Hayekian capital structure concerns about system-wide “malinvestment” account for this downturn up until the collapse of NGDP? What if the damage done by these malinvestments, magnified by fragility that high leverage produces, made stability of NGDP harder to achieve for the Fed?

I’m on board with your story that the Fed failed by letting nominal spending collapse and that some notion of nominal spending stability is the right ideal. But could they have avoided it entirely with open market operations? Was the pause at a 2% funds rate the absolute worst policy at the worst time and thus accelerated the banking collapse such that the money multiplier shrank farther and faster and made countering the velocity collapse even harder than it otherwise would have been?

Have you written anything that digs into more details about this period and what should have been done in much more detail operationally?

22. January 2013 at 21:33

John, please read this: http://econfaculty.gmu.edu/bcaplan/whyaust.htm

And before Scott gets mad at you for seeming to ignore his comments that the Fed could have prevented *any* fluctuation in NGDP (especially without a futures market), it’s true he thinks that most of the trouble there could have been avoided – not simply by mechanically increasing the base, but by stabilizing the path of expectations with an explicit target, which makes it less likely for asset prices to collapse in the first place (big determinant of velocity).

23. January 2013 at 01:02

“Rebeleconomist, That would be a unmitigated disaster, as 99% of transactions are not for goods or services.”

Oh dear, Scott, you really will say anything to make a riposte won’t you? I thought you considered that the monetary base (even currency a couple of weeks ago) was what matters.

If we can cut out the spite, what I have in mind is transactions in some kind of divisia money. Wholesale asset transactions would count, but count less, because they would presumably be traded against wholesale bank deposits. I know it would not be easy, but I think that the advantage it would have is that it would give some weight to asset prices. Otherwise, assuming that a central bank can control consumer prices, asset prices are constrained by their relationship with consumer prices, and that is likely to lead to some nasty bumps along the way.

23. January 2013 at 03:51

Saturos,

I am not really an Austrian although I sympathise with many of their ideas.

We can be highly critical of this Bryan Caplan piece, so I would be careful in referring to it.

Didn’t know Rothbard was the only Austrian too…

23. January 2013 at 06:42

Geoff, Mankiw has a paper on why you want to target the stickiest prices in the economy, especially wages. I’d google that paper for an explanation.

John, So far as I know all business cycle theories predict that capital goods output will be much more volatile than consumer goods output. All you need is Milton Friedman’s Permanent Income Hypothesis. So that fact does not provide any support for Austrian econ.

Rebeleconomist, I love how you keep backing away from you claims while pretending like I am the one making the foolish arguments. You have self confidence, I’ll give you that. Although not quite at MF levels of self-confidence.

23. January 2013 at 08:00

Scott, I don’t know what claims you think I making, let alone backing away from. I am trying to explain my alternative to NGDP targeting: inflation targeting, but with a more suitable inflation index. This is not such an eccentric idea; it goes back at least to Alchian and Klein in 1973.

23. January 2013 at 09:39

greece inflation explained

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2013/01/fed-watch-is-there-a-big-inflation-mystery-in-greece.html

24. January 2013 at 07:11

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, Mankiw has a paper on why you want to target the stickiest prices in the economy, especially wages. I’d google that paper for an explanation.”

Thanks! Conveniently, I think I have read that paper before. I didn’t know you shared Mankiw’s view on this. Fair enough.

Concerns:

1. Mankiw assumed zero correlation of shocks between economic sectors.

2. Mankiw did not address any potential endogeneity problems in his model, namely, the potential correlation between inflation targeting itself, and the volatility/sluggishness of prices. I guess this is not surprising, because that would require independent variables and coefficients that relate to price formation apart from monetary policy, which is impossible to do in data driven models of central bank economies.

3. In general, far too many “simplifying assumptions” (e.g. all sectors are equal, save price stickiness) that generate alarm bells for me.

The basic intuition however is all I can really go by, and as far as that is concerned, I find it impossible in my mind to separate monetary policy from observed price volatility/sluggishness (Concern #2 above), such that I can point to sluggish price X and conclude “THAT should be given more weight for monetary policy.” For I could very well be pointing to a price that is volatile/sluggish in large part because of historical monetary policy activity.

I guess I just can’t separate observed prices from monetary policy itself, and then pretend I am introducing new exogenous monetary policy prescription ideas that can “deal” with those volatile/sluggish prices.

8. June 2022 at 09:19

[…] Money Illusion | Marginal Revolution | Economics UK […]