Odds and ends

Here are a few items that I found interesting.

1. Are you thinking what I’m thinking?

Here’s one from the odd-but-true department: we are more likely to spend old, soiled money faster than crisp, new notes. You might object that this makes no sense at all – twenty dollars is twenty dollars, right? If fact, new research from Canadian scientists show that we are more likely to spend or gamble with currency that is old and worn.

Currency Isn’t Interchangeable

We think of money as being infinitely interchangeable. Any $5 bill is equivalent to any other. Five $20 bills are the same as one $100 bill. Unfortunately, it’s not true, at least from the standpoint of human behavior. We tend to spend small bills faster than large bills. So, if your wallet is full of $5 bills you’ll likely buy more stuff than if you have the same amount of money in larger bills.The magnitude of the difference in spending rates is startling. The Canadian reseachers found that subjects spent an average of $3.68 when given a crisp, new $20 bill, but more than double that – $8.35 – when given an old bill.

2. Excellent interview with Coase and Wang on China, and also the problem with modern economics:

Adam Smith, the founding father of modern economics, took economics as a study of “the nature and causes of the wealth of nations.” As late as 1920, Alfred Marshall in the eighth edition of Principles of Economics kept economics as “both a study of wealth and a branch of the study of man.” Barely a dozen years later, Lionel Robbins in his Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science (1932) reoriented economics as “the science which studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.” Unfortunately, the viewpoint of Robbins has won the day.

The fundamental shift from Smith and Marshall to Robbins is to rid economics of its substance “” the working of the social institutions that bind together the economic system. Afterward, economics has turned into a discipline without a subject matter, advocating itself as a study of human choices. This shift has been assisted by what Hayek (1952) criticized as the growing trend of scientism in the study of society, which took mathematical formalism as the only secure route to truth in the pursuit of knowledge. As economists become more and more interested in formalism and related technical sophistication, it becomes secondary whether the substantive questions that they choose to perfect their methods or to illustrate their theoretical models bear any resemblance to the real world economy. By and large, most of our colleagues are not bothered by the fact that what they profess is mainly “blackboard economics.”

We are now working with the University of Chicago Press to launch a new journal, Man and the Economy. We chose our title carefully to signal the mission of the new journal, which is to restore economics to a study of man as he is and of the economy as it actually exists. We hope this new journal will provide a platform to encourage scholars all over the world to study how the economy works in their countries. We believe this is the only way to make progress in economics.

We are very much aware that many of our colleagues whose work we admire do not share our criticism of modern economics. But our goal is not to replace one view of economics that we don’t like with another one of our choice, but to bring diversity and competition to the marketplace for economics ideas, which we hope most, if not all, economists will endorse.

3. Epistemic closure. Back in 2009 I was surprised to see conservatives warning that the Fed’s “easy money” policies would lead to high inflation. I would have expected conservatives to focus on market forecasts, which showed that inflation would remain low. Don’t conservative believe in market efficiency? Why were they making predictions that would lead to their views becoming widely discredited? I still don’t have an answer. But John Dickerson shows that conservatives in the Romney camp (and outside as well) did exactly the same thing during the recent campaign. It seems they genuinely believed Romney was winning, despite all the market forecasts showing he was losing. Originally I thought people like Karl Rove and Dick Morris understood reality, but were just playing to their audience. Now I think they were actually delusional.

4. A popular theme at the Fed challenge contest. One of my students at the recent Fed challenge in Boston told me that many of the teams mentioned nominal GDP targeting as a policy option. That’s good to hear. Apparently one team (Dartmouth?) cited Michael Woodford and me in support of NGDP targeting.

5. The Fed keeps evolving. Matt Yglesias points out that Janet Yellen is now supporting Charles Evans’ call for a more aggressive monetary stimulus. I just wish it was NGDP level targeting, not inflation and unemployment. In January Evans and Rosengren will join the FOMC. Recent statements by Dudley sound very promising. And the Board itself has 6 Obama appointees. I can’t imagine the Fed not offering more stimulus—we’ll need more stimulus even if we avoid the fiscal cliff. If we don’t avoid it, we’ll need much more monetary stimulus.

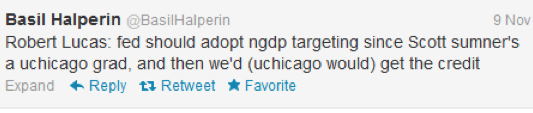

6. Take with a grain of salt. David Beckworth sent me the following:

University of Chicago undergrad Basil Halperin ran into Robert Lucas in the hall and asked him about NGDP targeting. This is what he said per Basil’s tweet:

Lucas has a mischievous sense of humor, so take that any way you wish.

7. Basil strikes again. And speaking of Basil Halperin, he was the student that recently asked John Taylor about NGDP targeting. David Beckworth reports that Taylor seemed somewhat receptive to the idea. David also has a good post on the bond vigilantes. He focuses on a rise in rates due to inflation and/or growth, whereas I focused on a higher risk premium.

Tags:

14. November 2012 at 07:18

Wasn’t Karl Rove the one who said: “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality””judiciously, as you will””we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out.”

I can attest to the feeling that smaller currency “feels” more divisible, whereas you tend not to want to “break in” your big bills…

And yep, there’s going to be no objection whatsoever from other faculty to the new journal, entitled, “Man and the Economy”. After what happened with the Friedman Institute, you’d think they’d be a little less tone-deaf to the liberal psyche…

I hope Basil appreciates his good fortune being where he is… he apparently ran into Bob Lucas the other day and only managed to ask him where the nearest bathroom was… #fail

14. November 2012 at 07:19

Doesn’t Bob Lucas think Chicago has enough econ Nobels already? Don’t answer that.

14. November 2012 at 07:22

Also, to everyone at TheMoneyIllusion.com (including MF): Happy Diwali! http://cdn.theatlantic.com/static/infocus/diwali111312/d27_56254456.jpg

(I’m not Sikh, this is just the best image in the set.)

For five days each year, I suddenly “rediscover” my Indian identity… that and Holi, of course (though there’s not much scope to do that properly here in Perth).

14. November 2012 at 07:29

So we have, what, four money illusions now?

14. November 2012 at 07:33

Yellen seems to have all but conceded that the Fed has in fact been taking 2% as a ceiling, and ignoring its dual mandate… stating the obvious (to smart central bankers) that way effectively admits that they were politically – economic gut-feeling motivated (cue Stephen Colbert quote) rather than rational mandate targeters.

14. November 2012 at 08:20

“we are more likely to spend old, soiled money faster than crisp, new notes.”

Sounds like Greshams law.

When the money changed circa 2000, I would hold onto the old bills and spend the new ones as I found the old ones more asthetically pleasing.

Karl Rove — Drink enough of the Kool-Ade and you will beleive it actually is wine. I see both liberals and conservatives who have spent far too long in their own echo chamber that they believe what they are saying over what they are seeing.

Risk Premium — what did you mean by it? When you said it, I took it to mean any rise in the differential between the Fed funds and Treasury rates, and growth expectations would be the most likely driver of that change. If we are going to examine rate rises due solely to an increase in default probabilites, it is a very differet set of circumstances.

14. November 2012 at 08:26

So, in a recession, issue smaller bills and slow down the replacement process.

14. November 2012 at 08:29

1. This phenomena is only explainable with subjective value theory pioneered by Menger. There is no inherent objective value in goods, including fiat bills. Just because it says $20, it doesn’t mean it is necessarily valued by subjects the same as every other $20 bill. This outcome is only “surprising” to those who haven’t yet learned of discoveries in economics made within, oh, the last 150 years. Maybe in another 2000 years monetarists will finally learn what the ancient Romans discovered under Emperor Diocletian circa 300 AD: Currency debauchery ultimately destroys empires.

2. This passage is rather confused. First, Robbins’ view has not “won the day”. Robbins’ view was dominant for around 20 years or so. But by the 1950s, his approach was abandoned in favor of positivism, which became the dominant methodology. This movement was heavily influenced and made popular by Milton Friedman. Positivism has since been the dominant approach. Modern economics is positivist, not a “means and ends” framework. The praxeological approach is very much “fringe”, where the only institutions using that approach are the Mises Institute, and George Mason University. To say that Robbins’ viewpoint has unfortunately “won the day” is, to me, just a misguided and unsolicited attack on praxeology. Second, Coase and Wang seem to want to advance the notion that the “substance” of economics is “the working of the social institutions that bind together the economic system.” This view, called “institutional economics”, is derived from Thorstein Veblen, a “progressive era” economist who viciously attacked production for profit, and held that technology must be divorced from the “ceremonial” sphere of society. Can anyone name another popular intellectual who both attacked profits and held that technology takes on a life of its own and determines the course of human society?

3. “I would have expected conservatives to focus on market forecasts, which showed that inflation would remain low. Don’t conservative believe in market efficiency?” You mean like how “the market” was predicting infinite increases in home prices prior to 2007…until home prices dropped? If anyone took “the market’s” advice in 2006, they would have got creamed. It was the anti-EMH investors who saved their portfolios. BTW, which conservatives predicted high inflation by 2012?

4. Austrian Business Cycle Theory is now a part of the CFA curriculum. CFA is private. Fed contest is public. Ha.

5. Is that comment consistent with your view that monetary policy should be 5% NGDP growth come hell or high water? You’re saying here that “we” need more inflation for non-fiscal cliff reasons. OK, that probably means getting NGDP growth up from 4% to 5%, right? Then you say that if the government doesn’t avoid a fiscal cliff, then “we” need even more inflation. OK, doesn’t that mean more than 5% NGDP growth?

6. There is usually some truth in humor. That’s the ultimate reason why morally suspect political strategists do what they do. For recognition from other morally suspect political strategists.

7. Beckworth: “…the point is that risk-adjusted real returns elsewhere should rise if bond markets expects higher inflation.” And that’s why I’m not a market monetarist.

14. November 2012 at 08:34

Is there a post somewhere that details the drawbacks to targeting unemployment rather than inflation or ngdp?

14. November 2012 at 08:41

You asked, “Don’t conservatives believe in market efficiency?”, which of course makes me think of competing monopolies. Two books in this regard: Michael Heller(“Gridlock Economy”, 2008), wrote of the castle tollbooths on the River Rhine, and Barry C. Lynn wrote “Cornered: The New Monopoly Capitalism and the Economics of Destruction”. in 2010.

One of my favorite MRU videos thus far further explores the river Rhine episode in the Double Marginalization Problem video. A second viewing allowed me to imagine the flow of money as a river where water (money) can be captured, and you can see why I envision this as such a good rationale for NGDP: in part to prevent unnecessary deadweight loss between competing monopolies. It seems that’s one aspect people don’t always understand, as to how NGDPLT can eventually assist in the creation of better wealth capture overall. Deadweight loss and overall inefficiencies happen because no one really wants to think about which upstream castles are capturing flow in such a way that the flow is dimished downstream. NGDP points out how much water is flowing at various points…who wants that clarification, when it may show how some actors have already distorted the flow! The Fed of course is seen as exogenous, putting more water into the river when too much is taken out. But exogenous solutions have to be applied when endogenous ones are not accounted for (supply side). The conservative may not like the additional flow, but he doesn’t want to lose the right to put more water in when it serves his purpose, therefore he supports interest rate targeting and the “tweaking” it allows. But NGDPLT does not allow the same tweaking! Therefore he may not want to show (through NGDPLT) how much water is actually flowing, so he can retain the right to additional flow if needed. He may encourage more flow (stimulus) when the additional flow can be captured by his castle on the river.

14. November 2012 at 09:44

Becky Hargrove:

A second viewing allowed me to imagine the flow of money as a river where water (money) can be captured, and you can see why I envision this as such a good rationale for NGDP

“The phenomenon of money occupies so prominent a position among the other phenomena of economic life, that it has been speculated upon even by persons who have devoted no further attention to the problems of economic theory, and even at a time when thorough investigation into the processes of exchange was still unknown. The results of such speculations were various. The merchants and, following them, the jurists who were closely connected with mercantile affairs, ascribed the use of money to the properties of the precious metals, and said that the value of money depended on the value of the precious metals. Canonist jurisprudence, ignorant of the ways of the world, saw the origin of the employment of money in the command of the State; it taught that the value of money was a valor impositus. Others, again, sought to explain the problem by means of analogy. From a biological point of view, they compared money with the blood; as the circulation of the blood animates the body, so the circulation of money animates the economic organism. Or they compared it with speech, which likewise had the function of facilitating human Verkehr. Or they made use of juristic terminology and defined money as a draft by everybody on everybody else.

“All these points of view have this in common: they cannot be built into any system that deals realistically with the processes of economic activity. It is utterly impossible to employ them as foundations for a theory of Exchange. And the attempt has hardly been made; for it is clear that any endeavour to bring say the doctrine of money as a draft into harmony with any explanation of prices must lead to disappointing results.” – Mises, Theory of Money and Credit, pg 461.

14. November 2012 at 09:54

“If it is desired to have a general name for these attempts to solve the problem of money, they may be called acatallactic, because no place can be found for them in catallactics.

“The catallactic theories of money, on the other hand, do fit into a theory of exchange-ratios. They look for what is essential in money in the negotiation of exchanges; they explain its value by the laws of exchange. It should be possible for every general theory of value to provide a theory of the value of money also, and for every theory of the value of money to be included in a general theory of value. The fact that a general theory of value or a theory of the value of money fulfills these conditions is by no means a proof of its correctness. But no theory can prove satisfactory if it does not fulfill these conditions.” – ibid, pg 462.

14. November 2012 at 10:25

I don’t understand Beckworth’s argument. The attack of the bond vigilantes itself is an -alternative explanation- for rising real interest rates, not a signal that real interest rates are rising due to growth. Indeed, one would expect the vigilantes to attack precisely because growth is low (thus reducing the expected long run tax base and exacerbating expected repayment difficulty).

The fact that a particular party is going short [Treasury] bonds based on a belief in – and attempt to create belief in – default risk in the bonds themselves is not an indication that the broader market is recovering (much less that a broader market recovery is supported by aggregate demand).

I understand that portfolio rebalancing can stimulate AD but it would require the bond vigilantes to actually move the market permanently to a higher equilibrium – and the fiscal authorities to take no responsive action – for this to be an effective stimulant.

This strikes me as unlikely in the case of Treasuries. No private entity has that kid of war chest, and demand for Treasuries is still high. The outstanding debt stock is in the trillions; how much of it do you need to [demonstrably be able to] sell to move the market? Note that the “vigilantes” have the same problems that the Fed does, and none of the inherent credibility [in selling currency] of the ownership of a printing press.

14. November 2012 at 10:33

MF,

When we don’t attempt to bring money into harmony with prices, we turn a blind eye to the gauntlets already laid at the head of the river, where an economic environment was already set out which left catallactics possible only on an abbreviated scale. The definition of MOA serves as a flashlight deep into the castles, where their keepers were allowed to secretly set their tolls not just for end goods but also intermediate goods. By looking away, we don’t see the valuation process itself which exploits the most basic forms of human need. And so the valuation process becomes even more “mysterious” and publicly unseen than the obfuscations of the zero bound.

14. November 2012 at 10:54

GMC:

“The fact that a particular party is going short [Treasury] bonds based on a belief in – and attempt to create belief in – default risk in the bonds themselves…” But how do the bond holders go short on treasuries? They have to buy some other asset, so by default they start the portfolio rebalancing.

14. November 2012 at 11:27

“we are more likely to spend old, soiled money faster than crisp, new notes”

Guilty as charged. Old dirty ones have been in all sorts of unsavory places. I feel like I need to carry Purell with me. I sort them to the front of the wallet and spend them first. Plus lots of low denomination bills make the wallet too thick.

14. November 2012 at 11:31

For $1, at least, new and crisp bills definitely have more utility over old and worn ones: worn bills are less likely to be accepted by vending machines.

14. November 2012 at 11:32

Also dirty money is more likely to rip, and more likely to be rejected by vending machines, self-checkout stations, parking kiosks and such. Machinable bills are have additional convenience value above and beyond the OCD ick factor.

14. November 2012 at 11:33

Becky Hargrove:

Prices are determined by exchanges of goods against money. Money isn’t abstracted away from prices, such that some sort of minimum “flow” of money has to exist or else the “flow” of money will be insufficient to “water” the prices.

The very gatekeepers that you claim can solve the problem of MoA, cannot do it. The non-market money flow they unleash hampers our ability to set market prices that reflect true marginal utilities of goods and services, both cross sectionally and inter-temporally. Production in the division of labor becomes thrown upon an unsustainable path that requires future, PAINFUL, corrections. This is the case for all rules based money printing. No non-market rule can avoid this.

Viewing money as a water flow makes it impossible to integrate money into a science of exchanges. This is precisely why you believe money belongs primarily to MoA, where MoA is a concept that can be abstracted away from exchanges, as if prices are determined ex cathedra and require a minimum quantity of “flow” or else poor people die of starvation.

By looking away from the problem of exchanges, you end up exacerbating the very problem you think only continued non-market money “flow” can solve.

14. November 2012 at 11:50

The notes one is a good argument for competition in note printing, since different notes have different demand functions and note production allows for competition.

We actually have something very close to this in Scotland, with a profit motive very clearly present when ATMs charge, since Clydesdale, RBS and HBOS all print their own notes. I’m partial, when carrying a lot of notes, to having a mix of the three.

http://www.vk3ukf.com/vk3ukf_files/AllNumis/ScotsNumis/BankOfScotland/5PndBrig/ScotlandBrigOdoon.jpg

https://weightoncoin.co.uk/images/Clydesdale%205%2019th%20Jun%202002.JPG

http://weightoncoin.co.uk/images/RBS%20St%20Andrews%205%20Pound.jpg

14. November 2012 at 12:36

“4. A popular theme at the Fed challenge contest. One of my students at the recent Fed challenge in Boston told me that many of the teams mentioned nominal GDP targeting as a policy option. That’s good to hear.”

No, it’s not!

RGDP 3%, P 2%, NGDP about 5%.

“Something happens”. RGDP 1%, P .5%, NGDP about 1.5%.

Next, RGDP 1%, P 2%, NGDP about 3% and stays there.

What happens if P is raised to 4% and RGDP starts falling? Explain.

14. November 2012 at 12:40

“What happens if P is raised to 4% and RGDP starts falling? Explain.”

Then we have supply side issues…

14. November 2012 at 12:43

Fed Up:

You silly man. Constant growth inflation ensures real growth is positive. Of course it’s not advertised that way, but that’s the crux.

Who knows, maybe we’ll see arguments like “Wow, the economy is worse than we thought! Looks like we have to have constant growth NGDP for juuuuust a little bit longer, and if things don’t improve…well, it’s because the economy was even worsererer than we thought. This stuff SHOULD work.” Keynesianism redux.

14. November 2012 at 12:59

GMC,

I did a new post that hopefully brings some clarity to what I was trying to say in the previous post.

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2012/11/bond-vigilantes-and-risk-premium.html

14. November 2012 at 13:01

MF,

Yes the metaphor did get shifted a bit, but the flow aspect was to illustrate a point. Don’t forget that gatekeepers are intertwined with wealth definition of all kinds, and some are more aware of that fact – consequently more responsive to potential solutions – than others. The MOA designation is presently more important mostly because of the asymmetries between production pathways for services and manufactured goods / commodities.

14. November 2012 at 13:19

How come I see very little alarm in the econoblogosphere that we have just lost 1,000 points off the Dow. I am very sympathetic to Sumner’s view, but I feel that his entire theory is on trial at the moment.

The Fed is incrementally adopting his policies and the market doesn’t seem to care.

14. November 2012 at 13:57

Becky Hargrove:

Yes the metaphor did get shifted a bit, but the flow aspect was to illustrate a point.

I challenged that point.

Don’t forget that gatekeepers are intertwined with wealth definition of all kinds, and some are more aware of that fact – consequently more responsive to potential solutions – than others. The MOA designation is presently more important mostly because of the asymmetries between production pathways for services and manufactured goods / commodities.

Asymmetries are exacerbated with inflation, because nobody can predict a priori where a new dollar will go.

14. November 2012 at 14:55

So much for the idea of stimulating demand by printing money.

14. November 2012 at 15:43

“Are you thinking what I’m thinking?”

Presumably what you’re getting at is that if money is perceived to be depreciating in value, we spend more, V increases and NGDP increases.

14. November 2012 at 16:01

Scott, you asked:

Why were they making predictions that would lead to their views becoming widely discredited?

The answer is: because they believed them. They wore their heart on their sleeves and put their faith on the line. They had nothing else to believe in. Turns out they were wrong and as a result ABC economics is totally discredited. They can never admit this because it is their faith. It is like asking an ancient Israelite to worship Baal.

14. November 2012 at 16:12

David:

Thank you, it helps. I suppose it helps to assume [I am sure you have good reasons for this view – me, I have to assume until I can take the time to understand them] that portfolio imbalance is the major cause of lagging economic growth. This seems to follow from a MMT/NGPLT view, however, since the result of open market operations is not only to create money but to reduce the free supply of safe assets.

This view, however, doesn’t seem to mesh perfectly with a speculative attack story. The only way bond vigilantes get this result (get ANY result) is if they are capable of selling enough Treasuries to meaningfully reduce the price of risk for (gulp!) the entire world financial system.

[This is another way of putting what always seemed like the bigger objection to bond vigilantes than whether their influence was positive or negative: the sheer size and liquidity of the Treasury market.]

Still, isn’t there a difference between reduction in risk premia created by risk of monetary inflation and reduced risk premia due to business confidence?

Put another way, aren’t we assuming that the only way to deal with debt is to print money to cover it or default? Isn’t a series of AD-reducing tax increases a concern?

14. November 2012 at 16:56

Rise of the bond vigilantes–

The term was coined in the early days of the Clinton adminstration. The 10-year treasury yield jumped from 5 1/4 to 8% in about 1 years time.

While there was a popular narritive that the bond market vigilantes were trying to punish the Federal government for running prolonged deficts, the narritive does not really hold with the facts.

But what did the economy do while rates were spiking? Real GDP growth increased from 1.8% real growth in the first 3 quarters of 1993 to 4.4% growth during the 4 quarters that yields were rising. About halfway through this period of rising rates the Fed began to tighten the money supply.

Rates rose in a natural reaction to increasing AD / expectations of monitary tightening, increased risk of inflation.

14. November 2012 at 17:07

ChargerCarl said: “”What happens if P is raised to 4% and RGDP starts falling? Explain.”

Then we have supply side issues…”

Could be. I haven’t heard the NGDP targeters specify how they want to raise P other than future “expectations” feeding back to the present. I don’t buy that argument by looking at budgets.

14. November 2012 at 17:16

“How come I see very little alarm in the econoblogosphere that we have just lost 1,000 points off the Dow. I am very sympathetic to Sumner’s view, but I feel that his entire theory is on trial at the moment.”

Lots of cross-currents. If Europe self-destructs, that is a deadweight loss for the whole world, that US monetary policy alone cannot make up. Yes, we could get back to the NGDP level, but not RGDP.

To some extent, the fiscal cliff has the same problems. Supply side hit from excessive taxes, and frictional losses from austerity. Not sure if Scott would agree with that, but I believe it’s a risk.

Third, the politicization of the Fed could become an issue again. I happen to think the degree of QE required to offset austerity is quite high. Will the Fed buy $100 billion in treasuries per month if necessary, or will they be afraid? And what if the Fed ends up owning the entire public share of the national debt, before we regain NGDP trend? This could happen because they’ve been undertargeting NGDP for so long, and because the deficits were never really the structural issue they’ve been made out to be…

14. November 2012 at 17:17

Fed up,

“What happens if P is raised to 4% and RGDP starts falling?”

increase P

14. November 2012 at 17:59

Professor Sumner –

To clarify a minor point, I asked Lucas/Taylor/Allan Meltzer about NGDP targeting at a panel presentation put on by the Becker-Friedman Institute to celebrate Milton Friedman’s 100th birthday. Lucas responded with his little joke; Taylor responded fairly positively; and Meltzer (to simplify his argument a bit) responded by saying that any rule is better than no rule, and the fact that the Fed has so much discretionary power is antithetical to what it means to be a democracy.

Also, I’m on the Fed Challenge team at UChicago and can confirm what your student said about NGDP targeting being a hot topic among Fed Challenge teams. I suggested that our team advocate NGDP targeting, but in the end we decided against doing so more due to time constraints than because of any problems with the policy itself. The Chicago Fed’s district competition isn’t until this Monday, but I’ll bet (and have heard from friends at other universities) that NGDP targeting will be mentioned by other teams as well.

14. November 2012 at 18:01

Major_Freedom said: “Fed Up:

You silly man. Constant growth inflation ensures real growth is positive. Of course it’s not advertised that way, but that’s the crux.”

Exactly. Just because price inflation remains positive does not mean RGDP will remain positive.

14. November 2012 at 18:31

Liberal Roman, You said;

“The Fed is incrementally adopting his policies and the market doesn’t seem to care.”

This is a common mistake. The effect on QE3 was 100% priced into stocks on September 13th. Additional movements in stocks are caused by factors that represent “new information.” There is no “wait and see” in macro, no waiting to see how QE3 works out. We knew all we’ll ever know on September 13th.

I’m no expert on finance, but common sense suggests that Obama’s proposal to raise the tax on dividends from 15.0% to 43.5% would depress stock prices. Investors will keep a far smaller share of the earnings from stocks. The stock market seems increasingly convinced that this increase will occur.

Basil, Thanks for the info. And I wish the Chicago team well—I’ll be rooting for them to finish second in the finals.

14. November 2012 at 20:27

Regarding taxation from dividends, there are a lot of investors who won’t see the dividend tax increase. Corporate owners don’t have an exemption, 401(k) and retirement accounts defer taxes.

However, what I expect we will see, is that companies that have cash will use that money to buy-back their shares rather than pay a dividend.

14. November 2012 at 22:02

You should read this Garret Jones post on the relative efficacy of spending cuts vs tax increases. If you follow the link to the IMF paper, there is a very interesting discussion on pp 27-28 of how the difference could be attributable to different monetary responses. But if true, that would really drive home your point that the Fed controls the path of NGDP.

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2012/11/which_hurts_mor.html

15. November 2012 at 00:30

Doug M, shares are only worth the NPV of the dividends they can ever pay…

Is he actually gonna raise them to 43.5%? That’s just insanity. And of course I doubt debt will be taxed so heavily, so…

wjaredh, The Fed doesn’t ultimately control real variables like unemployment, it can only estimate where real variables would be if nominal variables were where they should be… also, the 1970s.

Basil, what do all the Fed people think when they hear the kids start talking about NGDP targeting… ?

15. November 2012 at 00:36

When I was working in the underground economy—off the books cabinet work in a housing development—I was always paid in crisp $100 bills. It made an impression, and I copied that habit when paying others in cash.

Related to soiled money: Would you drive to the next town to buy a very high quality new suit for $200 marked down from $1100, or to buy a car marked down to $40,000 from $41,000 (all else being equal, like financing).

No one cares about $1,000 saved on a $41,000 purchase, but saving $900 on a suit is compelling.

15. November 2012 at 00:51

@Basil Halperin – What? Your ECON101 lecturer was John Freaking List??? *seethes with jealousy*

15. November 2012 at 05:24

MF

“Maybe in another 2000 years monetarists will finally learn what the ancient Romans discovered under Emperor Diocletian circa 300 AD: Currency debauchery ultimately destroys empires”

Maybe in 2000 years you will learn what the Ancient Greeks (Athenians) discovered under the leadership of lawmaker/philosopher Solon (greatest ancient Greek figure). They understood that new money creation is necessary in certain circumstances and went ahead and did that (Seisachtheia) reducing nominal debt levels in their economy and getting real benefits out of it (does the Golden Age of Athens ring a bell???).

Please don’t read about Seisachtheia in wikipedia but rather try some classics peer reviewed journal papers that extensively analyse what the reform was all about. I’m sure to your surprise you will find that they actually decided to increase the money supply back then.

I really don’t understand, if the Ancient Athenians had the flexibility to figure out that manipulating the money supply can be beneficial why you are being so dogmatic and inflexible arguing that money is some kind of deity that needs to be Fixed at all times? need to wake up

15. November 2012 at 05:53

What! Athens was founded on monetary stimulus? I never knew that!!!

15. November 2012 at 05:54

Sarkis, could you give me a link to one of the relevant papers on JSTOR?

15. November 2012 at 05:56

Topic for research – did the ancient Athenians suffer from sticky nominal wages??

In all seriousness, though, I can’t imagine that the money supply expansion was necessary except for Solon to earn seignorage from creditors. The debt forgiveness was by fiat, wasn’t it?

15. November 2012 at 07:34

@Saturos

Doug M, shares are only worth the NPV of the dividends they can ever pay

This isn’t quite true, not if the firm can and is expected to buy back its shares.

15. November 2012 at 07:47

When it comes to the growth of economic knowledge Coase is worth more than 100,000 math economists.

Make that 1,000,000 math economists.

15. November 2012 at 20:15

Doug M said: “Fed up,

“What happens if P is raised to 4% and RGDP starts falling?”

Employment falls, debt defaults happen, workers stop borrowing, MOA/MOE (currency plus demand deposits) falls.

And, “increase P”

Labor market oversupplied, wages stay the same, real earnings go even more negative, RGDP falls.

It is also possible real AS falls as companies remove capacity to attempt to retain pricing power.

Rinse. Lather. Repeat. The economy starts spiraling backwards in time to a lower level.

16. November 2012 at 06:17

Saturos

“Topic for research – did the ancient Athenians suffer from sticky nominal wages??

In all seriousness, though, I can’t imagine that the money supply expansion was necessary except for Solon to earn seignorage from creditors. The debt forgiveness was by fiat, wasn’t it?”

There are quite a few papers out there. Check this one for a description of Seisachtheia.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/626262

This is what Aristotle had to say:

“But even before his legislation, he had proceeded to a cutting off of debts and successively to an increase of metra kai stathma (measures and weights) kai nomisma (coins). For, under his rule, the metra became greater than the pheidonia metra, and the mina that before had a weight of seventy drachmai was filled with one hundred. For, the old coined piece was a didrachm. And he also established weights (stathma) corresponding to the coinage (nomisma), a talent being sixty-three minai; the stater and the other weights were increased in proportion to these three minai.”

Based on Aristotle and other ancient sources Solon actually was the first person in recorded history to enact in monetary easing. He fundamentally changed the relationship of Athenian coins with silver and generally reduced the nominal value of debts and interest payments.

Some of the details are disputed but nevertheless it is generally accepted that he increased the amount of coins in circulation without adding extra silver or gold in the Athenian treasury (as a gold standard system requires). It is unlikely he had any personal gain and in fact he left Athens for 10 years (so that he wouldn’t be forced to re-write the constitution).

One view is the following:

Solon proceeded by two steps. After having specific what the new metra are, he remarks incidentally: “For, the old coined piece was worth two drachmai.” This means that as a first step, the original stater of Aiginetic weight, which had been issued as 2 drachmai, was made by Solon equal to 3 drachmai. Something of the sort had taken place in Corinth, where the stater was equal to 3 drachmai and where there was a mina equal to 2/3 of Aiginetic mina. According to Aristotle this brought about a “cutting off” of debts.

The earlier system was based on a mina of 432 grams (16 Roman ounces) multiplied by 1½ and reduced by 1/21 (pheidonia metra) so as to result in a mina of 617.145 grams. This Aiginetic mina was divided into 50 staters, each of 2 drachmai. Solon first abolished the multiplication by 1½ and then abolished the reduction by 1/21. One hundred new drachmai should have been equal to 66.66 of the old, but because of the increase in the weights they became equal to 70 old drachmai (21/20 * 66.66 = 70). There was a practical reason for proceeding in two steps. Some historians have assumed that Athens could, like a modern state, withdraw the old coins and issue new coins overnight. In reality the old coins continued to circulate and new coins were issued at the slow rate allowed by ancient minting techniques. Those who had old coins could pay counting an old didrachm for 3 drachmai.

He further made subsequent changes to weights presumably because he needed to reduce real debts too.

16. November 2012 at 10:30

Sarkis:

So…we’re going on the same path as ancient Greece?

Neato.

16. November 2012 at 13:41

ok admittedly the ancient Greeks didn’t do very well after the 5th century BC but that was due to politics rather than economics. Anyway I simply making the point that a monetary expansion can be useful.

In general I’m wondering if you are right criticising the monopoly in money. I haven’t seen anyone over here addressing that fact or arguing against a competitive system in money. The only reasons I can think of that the current monopoly may be preferable than a competitive system are credibility and stability.

Putting that aside and considering the current system I’m more convinced by the Market Monetarist arguments rather than yours.

17. November 2012 at 23:48

Sarkis:

ok admittedly the ancient Greeks didn’t do very well after the 5th century BC but that was due to politics rather than economics.

You don’t think the latter influenced the former?

Anyway I simply making the point that a monetary expansion can be useful.

For whom exactly? I am not gaining anything if you receive newly printed money in exchange for your goods/services.

In general I’m wondering if you are right criticising the monopoly in money.

Ask any economist on their ideas concerning monopolies: Tendency towards increasing costs and decreasing quality.

I haven’t seen anyone over here addressing that fact or arguing against a competitive system in money. The only reasons I can think of that the current monopoly may be preferable than a competitive system are credibility and stability.

The electronics market is not credible? It is not stable?

Putting that aside and considering the current system I’m more convinced by the Market Monetarist arguments rather than yours.

Not concerned with what “convinces” you. I am concerned with what is true and what works. Competition breeds improvement.

18. November 2012 at 06:39

I find 6 amusing, but for a different reason: that Lucas would not think of his apparently fundamental ‘critique’ when discussing NGDP targeting suggests that it is indeed a gun that only fires left.

Scott, please can you or someone else address the Lucas critique wrt NGDP targeting?

Here is an example of what I’m talking about:

http://bubblesandbusts.blogspot.co.uk/2012/05/ngdp-targeting-changing-policy-changes.html

18. November 2012 at 11:25

MF

Thanks for your reply.

I understand that you are not concerned with what convinces me. Though if I represented the average young PhD level Economist that, to put it crudely, is trying to: Firstly understand “how things work in the real world” and secondly “can/should we improve the current system?”. One data point would suggest you are not very convincing to these kind of people.

What I’m interested about is: if we got rid of the fed and allowed a bunch of private issuers of money to operate in a presumably competitive market for money then would that “improve” social welfare? If yes in what way?

I thought that the fed is not a (typical) monopolist since they do not have a mandate to maximise profits but rather achieve full employment/price stability (even at a loss?).

Considering that a market solution may suffer from market imperfections such as asymmetric/imperfect information, its not clear to me how this would be better. Isn’t the fed the optimal provider of money given their objectives?

MF

“Competition breeds improvement.”

What kind of improvement would a competitive market bring to the table? What if this improvement made one provider of money dominant? Would you then intervene to bring back “competition” or allow a possible evolution into a new “fed” (presumably a profit maximising entity this time)?

Don’t know if these questions are relevant but we do not teach the possibility of competitive money over here in the UK and I’m not aware of the implications.

18. November 2012 at 12:53

Sarkin:

I understand that you are not concerned with what convinces me. Though if I represented the average young PhD level Economist that, to put it crudely, is trying to: Firstly understand “how things work in the real world” and secondly “can/should we improve the current system?”. One data point would suggest you are not very convincing to these kind of people.

I am also not concerned with what “convinces” a person who happens to be a “young PhD level economist.”

“Convincing” is simply not my standard of success, nor is it a foundation for concluding whether I am right or wrong.

What I’m interested about is: if we got rid of the fed and allowed a bunch of private issuers of money to operate in a presumably competitive market for money then would that “improve” social welfare? If yes in what way?

The same way that “allowing a bunch of private issuers of” food, clothing, medicine, electronics, housing, automobiles, textiles, entertainment, and every other good and service, “improves social welfare.” Consumers are, and hence consumption is, best served when producers have to compete for their solicitation. When they do not have a monopoly that enables them to screw up yet still retain ownership and control over the means of producing said good or service.

I thought that the fed is not a (typical) monopolist since they do not have a mandate to maximise profits but rather achieve full employment/price stability (even at a loss?).

This is a myth. This is the story they advertise so as to retain their monopoly. They are not altruists. The Fed does not exist to achieve full employment nor price stability. The Fed exists to serve the banks and the treasury, period.

They “target” a rate of inflation that pisses off people the least. Their track record for influencing employment is abysmal, but because they are a monopoly, consumers cannot bankrupt them and solicit a superior provider.

Considering that a market solution may suffer from market imperfections such as asymmetric/imperfect information, its not clear to me how this would be better.

Information asymmetry exists in every production. Humans lack perfect knowledge. Consumers don’t have the information about computers that the sellers of computers have, but that doesn’t mean that private competition isn’t the best for the consumer!

And if you want to talk about information asymmetry, then the Fed contains a very high amount of asymmetry. The public by and large does not know what they are doing. They are not fully audited. The Fed fights back against full auditing, precisely because they benefit themselves in secrecy, which harms those who are forced to accept dollars (to pay taxes, and pay legal costs enforced by the US dollar standard courts, etc).

Isn’t the fed the optimal provider of money given their objectives?

No.

“Competition breeds improvement.”

What kind of improvement would a competitive market bring to the table?

The same improvement that competitive food production brings to the table.

What if this improvement made one provider of money dominant?

If competition is open and free, then one dominant provider would mean that one dominant provider is actually better serving consumer preferences.

Would you then intervene to bring back “competition” or allow a possible evolution into a new “fed” (presumably a profit maximising entity this time)?

No intervention is necessary when one provider is so good that consumers willingly choose them over everyone else.

Don’t know if these questions are relevant but we do not teach the possibility of competitive money over here in the UK and I’m not aware of the implications.

Of course not. Competitive money would drastically reduce the income and power of the very people who have a dominant share of the education system in the UK. The government would lose. That is why the government finances and sets up education curricula that does not teach the benefits of competitive money. The banks would also lose. That is why the central bank and the banks finances universities and economists who are apologetic towards monopoly in money, rather than pro-free market in money.

18. November 2012 at 13:09

Sarkin:

Information asymmetry is as a rule higher between (non-competing) government and citizen, than (competing) producer and consumer. So if you have a problem with asymmetry in X, it makes little sense to have government in charge of X.

18. November 2012 at 14:29

The advantage of a competitive market predominately lies in the elimination of a deadweight (efficiency) loss that arises from monopolies. Is that a problem with the current system?

In every other product market we judge things based on price and quantity but in the money market what is the price? Usually we assume that the “price” of money is the rate of interest (opportunity cost) that is determined in the bond market by supply and demand. We also assume that the supply of money does not depend on the interest rate (perfectly inelastic supply). It seems that money is a special case of a good isn’t it? Not clear if your arguments for money competition based on other goods apply here. If you think they do apply then in what way exactly?

What would be the cost of changing the current monopoly into a competitive market and is that even feasible? (in theory yes but in practise?)

Wouldn’t a market solution be more risky in the sense that if systemic shocks may affect the rest of the economy disproportionally?

What would be the unit of account with multiple issuers of money? I think that having the dollar as the unit of account (and exchange) is preferable to having a commodity (gold) as the unit of account with multiple issuers of paper money if that is what you are proposing.

18. November 2012 at 14:44

I am asking these questions because perhaps we should start introducing this alternative system and the implications to undergraduates studying economics.

I don’t think that there is a government conspiracy to suppress these types of theories and what is being taught (at university level) depends on individual university departments led by people like us. If they believe it should be taught then it will be.

Anyway a department of economics should introduce students to the current debates in our discipline and then its the responsibility of the student to judge based on advantages and disadvantages if known. We already teach that competition is superior to other systems so there is not much of debate there. But in the case of money we remain silent or ignore other possibilities.

I think that is because potential advantages of competition in (100% fiat) money are not well understood. If the only other alternative is a gold standard with a competitive issuing of paper money then that is being already taught so no reason for our chat really.

18. November 2012 at 16:22

Sarkis:

The advantage of a competitive market predominately lies in the elimination of a deadweight (efficiency) loss that arises from monopolies. Is that a problem with the current system?

That is a problem with all monopolies, but I do not agree that this is the primary advantage of competitive markets.

In every other product market we judge things based on price and quantity but in the money market what is the price?

We also judge things based on their quality.

Prices are just ratios of exchange. The price of anything, including a monetary commodity in a competitive market, is the exchange ratios between that commodity and other commodities.

Usually we assume that the “price” of money is the rate of interest (opportunity cost) that is determined in the bond market by supply and demand.

That is a common misconception. Interest is not the price of money. The price of X is whatever is traded against X in the market. You can think of interest being the price of a loan, because that is what is being traded for the interest. The loan can consist of money, but a loan is not money qua money.

We also assume that the supply of money does not depend on the interest rate (perfectly inelastic supply). It seems that money is a special case of a good isn’t it?

I disagree. Money is a scarce commodity. Economic science applies to money no less than other scarce goods.

Not clear if your arguments for money competition based on other goods apply here. If you think they do apply then in what way exactly?

Money is a (scarce) commodity. It’s not so much that the science of others goods apply to money, it’s more that the same economic science applies to both money and other goods.

What would be the cost of changing the current monopoly into a competitive market and is that even feasible? (in theory yes but in practise?)

The costs would be subjective to the individual. Some individuals would gain (those who are on net harmed by inflation), other individuals would lose (those who are on net benefited by inflation).

In a society with slavery, what are the costs of abolishing slavery? Well, the costs would be subjective to the individual. Some individuals would gain (ex-slaves), other individuals would lose (former slave masters).

Wouldn’t a market solution be more risky in the sense that if systemic shocks may affect the rest of the economy disproportionally?

It is as a rule less risky to decentralize the production of X, than to centralize it. With a monopoly, one person or one group’s mistake affects the entire population. With decentralized production, one producer’s mistakes is localized to their particular exchange partners.

What would be the unit of account with multiple issuers of money?

I have no idea, and it is not necessary for me to know a priori what individuals would choose in a free market. Just like I would have no idea what slaves would do once they are free, and I am not obligated to explain to the masters what they would do, and convince the masters of what the ex-slaves would do, such that if the masters aren’t happy with my explanation, that somehow I haven’t proven my case that slavery should be abolished.

It is highly inappropriate to demand that anyone give you answers as to what people will do regarding X once they are free to buy and sell in X, before you will be convinced that freeing X up is warranted. The onus is actually on you to explain why buyers and sellers should not be free to use their property the way they see fit, to not make exchanges with each other according to their preferences, and to be initiated with threats of force and actual force to compel them to only use the monopolist’s X.

I think that having the dollar as the unit of account (and exchange) is preferable to having a commodity (gold) as the unit of account with multiple issuers of paper money if that is what you are proposing.

What you personally prefer, and what I personally prefer, has no bearing on what other individuals should use. It should be up to the individuals and their property. In a free market of money, if you don’t want to accept gold, then you don’t have to accept it. If I don’t want to accept cotton and linen notes, then I don’t have to accept them.

Let the market process decide what money potentials become popular and what money potentials do not become popular.

The same principle is the case in car production for example. If there was a monopoly in car production, and I said there should be competition, then it is not an argument against it to say that since you don’t prefer my particular preference of cars, that those cars should not be produced and sold. If I want to buy and sell those cars that you don’t prefer, then you really have no justification to force others to not buy and sell those cars. If they are not harming you or your property, then they should be able to buy and sell what they want. Sound like a familiar argument? It should. It’s the argument you and most economists make when the commodity in question is computers, or cars, or hamburgers, or t-shirts, or vacation resorts.

I am asking these questions because perhaps we should start introducing this alternative system and the implications to undergraduates studying economics.

It’s a testament to our time that a free market in money production is considered an “alternative system”. Anyway…

I do not have the power to dictate what all schools teach. What I can say is that since power centers (governments, banks, etc) gain a tremendous amount by being able to create money from nothing and have it imposed as legal tender by law, that convincing them to finance and put into public school curricula a system that would take away those gains if the aggressive force in money production was removed, is a very tall order. It will require a lot of intellectual and moral courage from economists, and this blog is proof that such intellectual and moral courage is a rare commodity.

I don’t think that there is a government conspiracy to suppress these types of theories and what is being taught (at university level) depends on individual university departments led by people like us.

It’s incentives. It appears as a conspiracy because the current monetary system benefits the powerful at the expense of the weak. Many universities are financed by the powerful people who benefit from inflation, so it not surprising that free market in money production is taught at so few schools.

Universities do not have full discretion, because they depend on financing. Who are the financiers at university X?

If they believe it should be taught then it will be.

They don’t believe it should be taught. Universities can earn lots more money when their customers (students) are given hundreds of billions of dollars in credit expansion created in the current monetary system. If a free market in money started tomorrow, then Universities would lose a LOT. Many profs would be fired. Union staff would be fired. Imagine the pushback. Many economists would suddenly find their funding dry up. The huge welfare employment program built on inflation would shrink tremendously. We would be talking about an education bubble popping.

A free market in money production will NOT come from today’s generation of intellectuals. Today’s generation of intellectuals have only supported, maintained and prolonged monopoly in money. No, a free market in money has to be grass roots. Students have to learn outside the officially sanctioned mainstream, and then challenge their profs who are almost universally too dimwitted to even consider it.

Anyway a department of economics should introduce students to the current debates in our discipline and then its the responsibility of the student to judge based on advantages and disadvantages if known. We already teach that competition is superior to other systems so there is not much of debate there. But in the case of money we remain silent or ignore other possibilities.

Yes, and that is precisely the problem.

I think that is because potential advantages of competition in (100% fiat) money are not well understood. If the only other alternative is a gold standard with a competitive issuing of paper money then that is being already taught so no reason for our chat really.

I am actually not wanting to impose gold money on you by law. I want to remove the aggressive impositions that prevent others from using whatever money they want in a freely competitive environment. If gold wins, so be it. If something else wins, so be it. It is not necessary, nor is it justified, for everyone to be forced to use a one size fits all by law.

Bitcoin income is still taxed in dollars, so Bitcoins cannot be considered a freely competing currency with the dollar.

18. November 2012 at 17:59

Unlearningecon. NGDP is not a policy instrument, so the Lucas critique doesn’t apply.

19. November 2012 at 03:14

MF

I think you are basing your arguments on freedom/liberty rather than economics and that is a mistake. Let me give you a non-money related example of why that is true.

We have two countries, 1 and 2 in which we have completely different policies on housing building. Both countries have laws protecting private property but the similarities end there. Country 1 is laissez-faire, individuals can build freely without restrictions. Country 2 has strict laws on what individuals can build and every building needs a planning permission. Country 2 has a department that decides on planning applications and the process is bureaucratic and expensive (no corruption though).

Based on your arguments and reasoning country 1 should have superior outcomes than country 2 with the strict laws and bureaucracy.

Not necessarily because what happened in country 1 is that people attempted to maximise the returns from the plots they owned building tall buildings with the main purpose of getting more apartment space per square foot of land.

Country 2 on the other hand did not allow that to happen restricting building sizes, requiring part of each plot to remain free and also protected older buildings that would have been teared down otherwise (older buildings tend to have less space per square foot of land).

The result is that the quality of life in country 2 is higher than in country 1.

Your analysis does not allow the presence of externalities. You assume that the market process will solve every issue but that is not always the case.

I asked what is the advantage of competition in money and you answered quality. But if you allow quality in money then you allow product differentiation so you already allow private firms with market power extracting surplus.

Again its not clear that changing the current system of money production into something else would help. I hoped for more direct answers in my above questions.

By the way country 1 and country 2 are real countries in Europe. Also plot owners did better in country 2 than the laissez-faire country 1. Can you guess why?

19. November 2012 at 05:20

Sarkis, two words: Coase Theorem.

19. November 2012 at 07:27

Sarkis:

I think you are basing your arguments on freedom/liberty rather than economics and that is a mistake.

I think you are basing your arguments on politics rather than economics and I don’t believe that is a mistake. I also think that you are claiming your arguments are based on economics, when economics is more of a weapon behind which you are using politics. Your politics is mistrust and resentment of private property in money production.

Let me give you a non-money related example of why that is true.

We have two countries, 1 and 2 in which we have completely different policies on housing building. Both countries have laws protecting private property but the similarities end there. Country 1 is laissez-faire, individuals can build freely without restrictions. Country 2 has strict laws on what individuals can build and every building needs a planning permission. Country 2 has a department that decides on planning applications and the process is bureaucratic and expensive (no corruption though).

I must interject. Country 2 does not have laws respecting private property rights. It has a state that violates private property rights. Not sure what the implications of that is for your argument. I think it’s not significant.

Based on your arguments and reasoning country 1 should have superior outcomes than country 2 with the strict laws and bureaucracy.

Superior outcomes based on what criteria though? My standard is individual property owners getting what they want. By the very fact that there is a state initiating coercion against private property owners, that right there means private property owners are not getting what they want, and hence by my standard, the outcomes are inferior by virtue of that aggression.

Not necessarily because what happened in country 1 is that people attempted to maximise the returns from the plots they owned building tall buildings with the main purpose of getting more apartment space per square foot of land.

Country 2 on the other hand did not allow that to happen restricting building sizes, requiring part of each plot to remain free and also protected older buildings that would have been teared down otherwise (older buildings tend to have less space per square foot of land).

The result is that the quality of life in country 2 is higher than in country 1.

Hahaha, you are just imposing your own subjective value judgment over and above the subjective value judgments of the private property owners. You aren’t doing economics here, you’re doing subjective value judgments backed by the force of government (politics).

By the standard of private property owners getting what they want, rather than what they don’t want because of coercion and therefore settle for, it is precisely Country 1 that has superior outcomes. For if private property owners want to build high rises, and are free to build high rises, then it would be an inferior outcome for them if a state used coercion to prevent them from doing that, as in Country 2.

Country 1 has property owners doing what they want, whereas Country 2 has the government doing what it wants and using coercion to prevent private property owners from doing what they want.

You just haphazardly judged that you personally prefer the outcomes in Country 2, whilst totally ignoring the preferences and judgments of the people of Country 2.

You’re thinking like a central planner.

Your analysis does not allow the presence of externalities. You assume that the market process will solve every issue but that is not always the case.

No, my analysis does not allow property rights violations. There are no negative externalities when property rights are respected. It is precisely in Country 2 that there are negative externalities. The state in Country 2 is imposing your preferences, which generates less than optimal outcomes for the actual property owners of Country 2. The very fact that coercion is present proves that the property owners of Country 2 are not getting what they want. That is inferior, not superior.

I asked what is the advantage of competition in money and you answered quality.

No, I said you forgot to take into account quality as one of the many factors that people take into account when deciding on what to buy. I did not say that quality is the only factor, nor even a necessary factor for all individuals.

But if you allow quality in money then you allow product differentiation so you already allow private firms with market power extracting surplus.

Business owners extracting surplus? OK, Marxoid.

Market power is derived from consumer preference, not coercion. There is no “surplus extraction” when a property owner produces and sells a good that others are willing to buy. Even if he earns 50% profit. The value is determined by the buyer and seller, not just the seller.

Why aren’t you complaining about “extraction surplus” in food production, or clothing production, and medicine production, and as a result, advocate that the state monopolize all these things as they do money? If that is your justification for state monopoly of money, then you would have to support full fledged socialism.

Again its not clear that changing the current system of money production into something else would help. I hoped for more direct answers in my above questions.

It is clear, you are unfortunately just having your mind clouded by anti-capitalist propaganda. I gave you direct answers.

By the way country 1 and country 2 are real countries in Europe. Also plot owners did better in country 2 than the laissez-faire country 1. Can you guess why?

There is no laissez faire country in Europe. And plot owners did not do better if there is coercion. It is silly to claim that initiating violence or threats of violence against people makes them better off. Plot owners do better when they can decide what to do with their own plots. You are just arrogating your subjective value judgment to the status of objective values, that’s all. You are ignoring the wants and desires of other people.

19. November 2012 at 07:29

Saturos:

Sarkis, two words: Coase Theorem.

http://mises.org/journals/jls/1_2/1_2_4.pdf

19. November 2012 at 07:35

ssumner:

Unlearningecon. NGDP is not a policy instrument, so the Lucas critique doesn’t apply.

Merely naming it something other than a policy instrument does not mean the critique does not apply. NGDP is being claimed by market monetarists as containing explanatory information (via historical data) that allegedly qualifies it as a statistic for monetary policy targeting. You are making the argument that NGDP movements have predictive power in where unemployment and output will go. You argue that because NGDP fell in 2008, the recession was worsened, and that if it didn’t fall, then the recession would have been lessened.

If you believe that you can predict the effects of a change in economic policy entirely on the basis of relationships observed in historical data, especially highly aggregated historical data such as NGDP, then OF COURSE the Lucas Critique applies!

UnlearningEcon, don’t listen to Sumner, he is wrong about almost everything.

19. November 2012 at 07:41

Sarkis:

In addition, I should have said that extraction surpluses are maximized for a monopolist. You say a private firm with market power can extract surplus, so your “solution” is to maximize power so much that there is no longer a market. That’s too funny. Why do you haters of laissez-faire so often think alike in this respect? “Private firms producing X! Oh no, we can’t have that! There will be large firms with market power! It’s better to increase that power by monopolizing it in the hands of those in the state. That ought to solve the problem of too much power with too few people.”

Goodness.

19. November 2012 at 13:50

MF

I guess then you are not aware of a competitive market where firms have no market power and they extract no surplus (profits). In this case social welfare is maximised. Of course all this is about economic profits rather than accounting profits.

If you allow for quality (rather than homogeneous money) then you deviate from a fully competitive model and go towards monopolistic outcomes (always due to preferences). To me it seems that you are proposing to get rid of the fed and replace it with oligopoly or with monopolistic competition.

The problem here lies in the definition of the fed. If the fed acts like a typical monopolist then any departure from that model is advantageous (always in terms of social welfare). Even a duopoly is better than a monopoly and the more competition (number of firms) the better.

If however the fed does not act like a monopolist then its not clear if an oligopoly or a monopolistic competitive market would be better. We would only be sure if we replaced the fed with a perfectly competitive market but that is not what you are proposing (quality would be the same across firms in such a market). My question is: How can we tell if the fed is behaving like a monopolist since their stated objectives are different than a monopolist. When asked about that earlier your answers were axiomatic:

MF

“This is a myth. This is the story they advertise so as to retain their monopoly. They are not altruists. The Fed does not exist to achieve full employment nor price stability. The Fed exists to serve the banks and the treasury, period.”

Still is there a way to find out if this is true and if yes how can we do that? I don’t think you’ve ever answered this question. Wouldn’t MM proposals make the fed act like a non-monopolist anyway?

I’m not a socialist nor an anti-capitalist. I’m just trying to have an open-mind about things and mostly to understand new (to me) ideas and concepts. My arguments above are based on basic economic theory. I understand the problem of information and that markets have the advantage of requiring very limited information to operate. I’m pro-market and anti-tax actually.

About the two countries example:

Country 1 http://www.foxysislandwalks.com/Athens/Athen-itself.jpg

Country 2 Mainly referring to the city of London.

Travel to these two cities and you’ll notice that in London (and other western European capitals) prices (and quality) increase as you move towards the city centre. Athens is unique in the sense that quality of life (in terms of clean air/ public space etc) and prices decrease as you move into the centre. Athens’ best areas (based on population preferences and price per square foot) are actually places that allowed construction under similar parameters to the ones crudely described in my example above.

Unfortunately Athens turned from the “Paris of the south” in the early 60’s to the current monster (referring to their peak of 2006) The lack of controls lead to a demolition of the vast majority of neoclassical buildings back then. In your world that is irrelevant if it is the result of market processes. You must admit though that market processes might have led to different outcomes if market participants knew that in the near future plots with these demolished neoclassical buildings would be the most desirable and expensive (per square foot of land). Imperfect information?

Definitely not an expert on this but most of the articles I’ve read about this subject point to same direction.

Coase theorem might not apply in my example because there are public goods involved. To be honest this was an extreme example. Still I think that there is a place for the state in our world and this example was simply trying to demonstrate that (unsuccessfully?). Do not flame me for using a crude example like that because I’ve seen quite a few posts of yours doing the same against MM theories.

19. November 2012 at 14:42

Sorry meant to say “in the near future plots with these, now demolished, neoclassical buildings would be the most desirable and expensive”

5. December 2012 at 08:12

Scott,

Sorry for such a late response I only just remembered this comment.

I think your comment suggests a narrow interpretation of the LC, one which has unfortunately been adopted by much of the profession. The question is not what we call a particular policy or policy relationship, but whether or not we can confidently assert that a statistically observed historical relationship (NGDP and RGDP in this case) can be expected to hold once we attempt to exploit it for policy reasons.

I mean, this case is incredibly similar to the Phillips Curve. Surely you can see the analogy?

9. August 2013 at 02:53

[…] behaviour of the economy. Scott Sumner in particular refuses to discuss transmission mechanisms or engage the Lucas Critique, and seems to be more concerned with making out he is an oppressed minority than […]

18. March 2017 at 06:44

[…] of the economy. Scott Sumner in particular refuses to discusstransmission mechanisms or engage the Lucas Critique, and seems to be more concerned with making out he is an oppressed […]