No Texas oil multiplier (dedicated to Adam Gurri and Noah Smith)

Tyler Cowen recently directed me to a post by Phillip Longman in the Washington Monthly, which attempts to debunk the “Texas miracle.” His main argument is that the boom in Texas is a product of the recent oil boom, not good economic policies. Even that is questionable, as lots of other places have large amounts of oil and gas but simply choose not to frack (Europe, New York, California, Mexico, etc.) But let’s accept the “Texas is lucky” argument for the moment; do the facts support this multiplier claim?

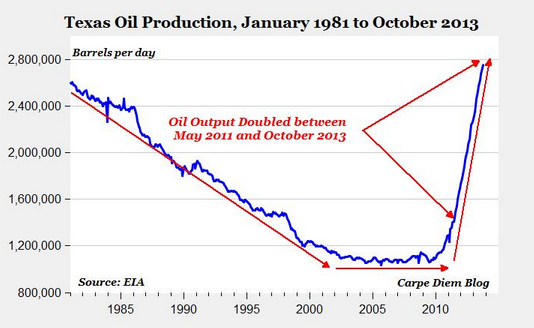

Unless you’ve been to Texas lately, you might have missed just how gigantic its latest oil and gas boom has become. Thanks to fracking and other new drilling techniques, plus historically high world oil prices, Texas oil production increased by 126 percent just between 2010 and 2013. . . .

To be sure, only about 8 percent of the new jobs in Texas are directly involved in oil and gas extraction, but the multiplier effects of the energy boom create a compounding supply of jobs for accountants, lawyers, doctors, home builders, gardeners, nannies, you name it. Saying that Texas doesn’t depend very much on oil and gas just because most Texans are not formally employed in drilling wells is like saying that the New York area doesn’t depend very much on Wall Street because only a handful of New Yorkers work on the floor of the stock exchange.

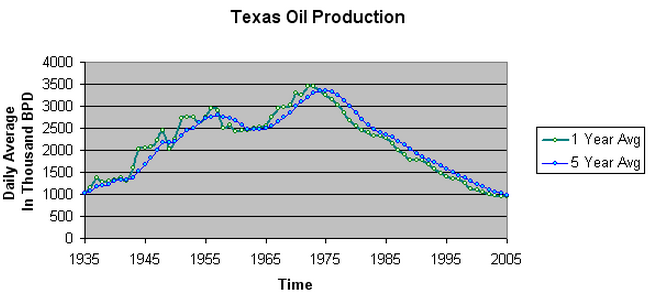

You’d think the editors of Washington Monthly would have at least checked the data, to see if his multiplier claim was accurate. It only takes 5 minutes. And as we’ll, see the data decisively rejects this argument. But first a bit of history about Texas oil production. Notice how it plunged in the decades after 1975:

Now look at the population growth by decade:

1970-80: 27.05%

1980-90: 19.89%

1990-2000: 22.74%

2000-10: 20.63%

Texas’s population grew at roughly twice the national rate for decade after decade, even as oil output was declining sharply. Now look at the recent trends in oil output:

So the Texas oil boom was quite recent, beginning about 2010. Now let’s look at the population growth figures before and after the recent boom:

2005-06: 2.55%

2006-07: 2.01%

2007-08: 2.02%

2008-09: 2.02%

2009-10: 1.85%

2010-11: 1.62%

2011-12: 1.52%

2012-13: 1.50%

Where is all the population growth from fracking? Where is the multiplier, the spinoff jobs for other sectors? I suppose you could argue that while Texas hasn’t seen any more population growth, the unemployment rate has fallen more sharply than in other states. After all, only 6% of the Texas workforce is unemployed, as compared to 6.7% for the country as a whole. The problem here is that unemployment in Texas peaked at 8.3% in February 2010, versus a peak of 10% for the US. So the fall in the unemployment rate in Texas has actually been smaller than for the country as a whole (even slightly smaller in percentage terms). The fracking boom has not had a noticeable effect on either population growth or unemployment.

Sometimes I think that Keynesians are so convinced that there is a “multiplier effect” that they don’t even both to check the data. At least Paul Krugman has the good sense to make the argument in terms of GDP, not population:

But I wanted to follow up on one particular point: the role of oil and gas in recent years. Longman concedes that these industries directly account for a fairly small share of the economy even in Texas, but argues that their rapid growth, combined with multiplier effects, makes them a much bigger story when it comes to Texas growth. Indeed. Let me put some numbers to this, using the BEA data on real GDP by state.

What you learn from these data right away is that Texas is indeed king of the extractive expansion. Nationwide, mining output, measured in 2005 dollars, expanded $29 billion between 2007 and 2012; Texas accounted for $22.7 billion of that expansion. Nationally, the expansion of mining was 0.2 percent of 2007 GDP; in Texas, it was 10 times that, 2 percent.

Oil extraction is very capital intensive, so I don’t doubt the Texas GDP numbers would look better than their population or unemployment numbers. But that’s not the big story, and even Krugman admits that there’s much more to the Texas growth story than oil. The big story is that people have been moving to Texas in large numbers for many decades, even decades when oil production was falling fast.

Sorry liberals, but there really is a Texas miracle, and it has nothing to do with “multipliers.” It is explained by the fact that working class people like to move to states with low living costs (due to flexible zoning), and businesses and high skilled professionals like to move to states with low income taxes. The working class cares more about the low living costs than the fact that Texas offers less expensive welfare programs than California. They come to Texas to work, not to collect welfare. The businesses bring them the capital they need to be productive workers.

My only quibble with Krugman’s post is that he leaves out the lack of a state income tax, which helps explain why Texas grows far faster than other south central states with hot weather and cheap houses. The big story is that people have been moving to Texas in large numbers for many decades, even decades when oil production was falling fast.

PS. I was going to take Sunday off, but was inspired to write this post by Saturos, who is of course right about the decline in quality of my writing. That’s what happens to grouchy old reactionaries. But when Keynesians keep throwing softballs over the center of the plate, it’s hard to step away. I know Adam Gurri doesn’t read my blog, but perhaps someone can tell him that Knausgaard has inspired me to adopt a maximilist approach.

Update: Some commenters suggested that the Texas miracle is due to cheap real estate. This post demolishes that argument.

Tags:

9. March 2014 at 10:33

I still wouldn’t overrate the size of the migration. The in-migration from other states is still dwarfed by immigration from Mexico and natural population growth (same thing for California).

Why doesn’t someone actually survey new migrants into Texas to see why they made the move? I doubt housing by itself was the primary reason, although it would be a strong sweetener if you already were thinking about moving for a job.

To be fair, you see a split on this among liberals. Some of us have been saying something similar for years, that California really needs to get housing expenses down in the major metro areas so that the higher-paying jobs don’t immediately get devoured by higher rent/mortgage expenses (of course, as Ryan Avent has pointed out, that also means a ton of jobs that just don’t get created in the first place).

It’s just we’re currently overshadowed by the big-city preservationists with money who want to freeze the city the way it was when they moved in, and by the advocates for poor communities full of renters who might get tossed out if rates go up (made extra ugly by the racial component, since many of them are in those rental areas because of historical prejudice in housing finance and options).

9. March 2014 at 10:44

“They come to Texas to work, not to collect welfare. The businesses bring them the capital they need to be productive workers.”

I really like Gurri, but he’s not ready to declare policy winners, he’s more an “on the one hand, on the other” guy. Hell, he spent a month reading neo-reactionary idiots, so he’s very good at consuming idiotic stuff….

But you are, after all, right Scott – the facts bear it out… so keep beating folks into submission.

9. March 2014 at 11:11

Brett, it’s all around you here in Austin, very few people have a Texan drawl. The town has gown 50% since I’ve been here (2007), I’d come to SXSW in early aughts, and the moment we had a kid coming, there wasn’t any thought about where to go after LA.

The arriving people are young tech and media folks… they are leaving professional markets in LA, NYC, SFO.

The skyline appears to change via cell division. We lose 40 and gain 150 move ins a day.

I grew up in Massillon Ohio, and there are a number of kids I went to HS living within two or three miles of me.

I sound nuts saying this, but I won’t be surprised if Austin doesn’t make a run at Silicon Valley in another decade. We just don’t have any of their issues. I truly doubt that property owners will agree to build vertical, or that the state public sector will take its boot off neck of businesses a tax payers. We’d have to have a massive win of our own (Google style), but it won’t shock me if we do.

9. March 2014 at 11:26

Scott,

To be fair, there are conservative Keynesians, such as Bernanke, Mankiw, and Feldstein(or at least used to be?). And not all liberals are Keynesian. I’ve seen Jeffrey Sachs be very critical of Krugkan’s crude Keynesianism.

9. March 2014 at 11:30

A little perspective:

It’s not like anything’s gone horribly, horribly wrong in San Francisco, New York or Boston. They continue to thrive and generate plenty of innovation and wealth.

BUT……they don’t allow new housing construction at remotely the rate that Texas does. That’s the key difference.

Matt Yglesias and Josh Barro have provided great insight on this issue:

http://thinkprogress.org/yglesias/2011/06/13/243972/the-secret-to-texas-success-they-build-houses-there

http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2013/05/23/fastest_growing_cities_in_america.html

http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2013-02-12/home-prices-drive-people-out-of-california

Also, here’s some great stuff on this from Lorenzo from Oz:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=26140#comment-318563

http://skepticlawyer.com.au/2014/02/19/robert-waldmans-really-clever-very-bad-idea

9. March 2014 at 13:15

Prof. Sumner,

I saw your update. Thought-provoking stuff!

But still, your argument is that Red State Texas’s state economic policies promote growth while Red States Oklahoma, Alabama and Arkansas’s state economic policies discourage growth?

Also, Texas has relatively high property taxes, doesn’t it?

Interesting but I’m still skeptical that differences in, say, tax policies between those states explains much.

I just sense that Texas has achieved a certain critical mass that’s ideal for growth. Lots of medium-sized cities within one mega-region.

The scale of Houston and Dallas attracts more and more people. Eventually, as Houston and Dallas reach the size and land limitations of NYC, L.A. and Chicago, traffic congestion and other issues will reduce their rate of growth…….

9. March 2014 at 13:21

I lived two years in Austin in the 1970s. It was nice. Hot and sticky though. Scholtze’s Beer Garden was high culture. No oceans. No mountains. No scenic deserts. Lots of greasy food, with the attempt at improving the bland fare by throwing jalepenos on top.

Texas has done the right thing by keeping things cheap…and Austin is considered the “garden spot” of Texas…Houston is hotter and stickier and smells bad…

9. March 2014 at 13:26

Travis—

The strange thing about Texas is that county assessors can tax your land to “highest and best use.”

So the process is heavy politicized and if developers want your land…

Texas is the Third World…you get good growth rates in Thailand too…

9. March 2014 at 13:27

I wonder if Longman realizes what a powerful pro-fracking argument he’s making here. If fracking in West Texas can boost the economies in Houston, DFW, Austin, etc to such an extraordinary degree, the beautiful pastoral landscapes cannot compete with that and you can more than pay for better water filtration/sanitation systems.

9. March 2014 at 13:59

Dear Commenters,

Here is a great old post by Ryan Avent for you to attack:

http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2009/08/what_makes_places_rich

“if you are in a multi-jurisdictional metropolitan area like Washington or New York, then the highly skilled may be persuaded to adjust their residence based on tax rates, yes.

But low tax rates will rarely be sufficient to pull the well educated to a new city altogether. Why? In part, because their value in the labour market is partially contingent on being close to others who are well educated. In part, because their real wages take into account amenity flows, and there are amenities which can be had in New York City that cannot be had anywhere else in the country, such as Manhattan life.

What we seem to be learning from the success of places like Texas and North Carolina is that metropolitan areas that can offer affordability (and this includes relatively low tax rates) in combination with a growing jobs base and a foundation of human capital (based on some pre-existing industry or high quality educational institutions) can grow their populations very rapidly, ultimately establishing the kind of dense, human capital rich agglomeration that will prove sustainable.

The question is whether affordability can be maintained over the long-term. A sprawling infrastructure is costly to maintain. As cities grow more dense, residents will begin to assert their NIMBYish concerns and housing supply will be restricted, causing prices to rise. Rapid growth tends to lead to unanticipated social ills, like congestion and air pollution, that will reduce the attraction of such places and prompt government interventions of various sorts. Like emerging markets, rapidly growing cities are destined to converge toward the policies and trends of older and more developed places.”

P.S.: Ben Cole, see that last sentence.

9. March 2014 at 14:03

not really sure that just low cost of living is the end all be all of the Texas ‘miracle’. been here for over 30 years now. and while we do have some spots with high property values, they are not the vast majority of the state (tend to be around the large cities, not around the smaller ones. and that might have more to do with the job growth we have had). and while we have some areas that have a pretty good incomes, we also have a vast majority that dont (we do have that average income about 30k a year). and oil has made it so that we dont need an income tax (we tax all of the oil and gas drilled in the state). we dont exactly end up with a low tax state (more like in the middle).

and we do have a few challenges coming our way. we are in a drought. we do have more than a few cities that are just about out of water and some that are. plus we have a problem with roads (latest ‘solution’ has been to take paved roads and make them into gravel ones)

9. March 2014 at 14:48

Gee, the “Texas because of oil” line sounds like “Australia has not had a recession since 1992 because of China”.

TravisV: Thanks for the plug 🙂

9. March 2014 at 14:55

The “Texas economic miracle” starts after 2005 (graph at link of the difference between the difference of the unemployment rate from the “natural rate” in the US as a whole and Texas).

http://twitter.com/infotranecon/status/442794967967088641

Basically Texas unemployment is higher relative to its typical level than for the US as a whole up until 2005 (oil boom onset) and it really takes off in 2008 (financial crisis onset).

The low taxes and zoning laws were all in place before then.

9. March 2014 at 16:26

Perhaps the “Massachusetts Miracle” is caused by fracking. After all, many of those Texas oil wells are owned by 1%-ers and foundations located in MA. I’d bet that MA ranks near the top of the highest per capital 1%-er oil well owners in the country. And the rising wealth of these people and institutions trickles down to the residents of MA enabling them to purchase German cars and socialized medicine.

Of course I write this partly to be provocative. But, the serious point that Krugman and Sumner are missing is that much of the “fracking wealth” created in Texas quickly leaves the state. Much gets paid in taxes and royalties on the wells. Much more gets paid in personal income taxes — often at a 50%+ MTR by the oil-field workers (thanks to ss+medicare and entitlement phaseouts). And still more gets paid in corporate income tax and capital gains tax. Any hypothetical in-state multiplier quickly gets dampened by the fact the majority of the money flows out of state on every single turn.

This is a point Krugman would gleefully make were he talking about New York funding a safety net to pull Nevada out of a housing crisis. But if Texas is pulling the rest of the country up by its bootstraps, well, what then?

9. March 2014 at 17:57

😀

9. March 2014 at 18:12

You’d think that by my age I’d have learned better than to mouth off on the Internet.

I believe you’re doing good work (not that you should care what I think) I’ve just lost interest in monetary policy. It was juvenile to express that as snark about you. I hope you’ll accept my apology.

9. March 2014 at 18:27

Everyone, I added an update that addresses the low property price argument. The bottom line is that Texas is the only fast growing state between Georgia and Arizona. The other 6 also have very low property prices. Oklahoma and Louisiana even have oil. New Orleans was once a corporate center for the oil industry, a competitor to Houston. Texas is special.

Thanks Adam, but don’t worry about it. You are right that my blogging has gotten repetitive and tiresome, I get very depressed when I look at my early posts, some of which were better. How did I actually write that stuff?

9. March 2014 at 18:40

OT, but Bernanke favored targeting the (internal) forecast during the height of the NGDP collapse:

We have been debating around the table for quite a while what the right indicator of monetary policy is. Is it the federal funds rate? Is it some measure of financial stress? Or what is it? I think the only answer is that the right measure is contingent on a model. As President Lacker and President Plosser pointed out, you have to have a model and a forecasting mechanism to think about where the interest rate is that best achieves your objectives. It was a very useful exercise to find out, at least to some extent, how the decline in the funds rate that we have put into place is motivated. In particular, the financial conditions do appear to be important both directly and indirectly””directly via the spreads and other observables that were put into the model and indirectly in terms of negative residuals in spending equations and the like. The recession dynamics were also a big part of the story. I hope that what this memo does for us””again, I think it’s extraordinarily helpful””is to focus our debate better. As President Plosser pointed out, we really shouldn’t argue about the level of the funds rate or the level of the spreads. We should think about the forecast and whether our policy path is consistent with achieving our objectives over the forecast period.

http://newmonetarism.blogspot.com/2014/03/monetary-policy-and-financial-crisis.html

9. March 2014 at 18:40

Back then you were definitely the insurgent. When I heard your first EconTalk interview it was eye-opening. I don’t know if it’s right to call you mainstream at this point, but you’re definitely bigger, and widely taken seriously. Maybe it’s more challenging to write from that perspective?

And anyway this very post is disproof that you’re repetitive or tiresome.

9. March 2014 at 18:43

Travis–

People who love Austin…need to admit that it is also host to UT and the state capital…those are big reasons it has attracted intellectuals…

I wish Texans the best of luck but there are nicer places to live in the Third World than Texas…

Scott Sumner: Your writing is fine. Most bloggers lay down a foundation and then rif off of that…it is inevitable; one tires of repeating same arguments…consider it like dating–the first few dates are high-brow, but then people get down to business…

9. March 2014 at 18:55

It’s likely that we’ll see IOC capex fall by $80 bn in the next 2-3 years, primarily related to high capex projects like deep water, Arctic and LNG.

Typical revenue per employee is this segment is around $400k, thus $80 bn represents a loss of approximately 200,000 jobs. The three main centers for this type of activity are Houston, Aberdeen (Scotland) and Stavanger (Norway).

If we assume 70% of related employment comes from these cities, then 140,000 jobs will be lost. Of these, figure 40-45% will come from Houston, or 60-70,000 jobs, all of them high paying.

These will be offset to a certain extent by US onshore oil and gas production, maybe worth +20k jobs; and the impact of opening to Mexico, worth relatively little at first, but potentially important down the line. In addition, US LNG facilities will have important contributions from the Houston engineering and manufacturing base, figure +10-20k jobs in the next 3-4 years.

So figure Houston takes a 40-50k hit to oil and gas jobs in the next 2-3 years or so. Then we’ll have a better sense of just how robust that Texas miracle is.

For those interested in macro oil theory, please see my presentation at Columbia University. Arguably the cutting edge in macro oil markets, if I say so myself.

http://energypolicy.columbia.edu/events-calendar/global-oil-market-forecasting-main-approaches-key-drivers

9. March 2014 at 21:56

Thanks for the article Professor,

However, I myself am a little but skeptical to say there is a “Texas Miracle.” You make good points about the fact that fracking boom can’t be really responsible for the job growth buy do you think there is some validity to other frequently cited concerns about Texas?

For example, Texas does have one of the highest poverty rates in the country (having trouble finding how much of this is due to immigration, but even so California has high immigration as well). And it also seems like poor and many middle class Texans have higher tax rates than those in California. This could potentially be a big problem since Texas has one of the highest percentages in the nation of workers who make minimum wage (and Texas’s minimum wage is at the Federal level).

Finally, lot of people talk about Texas’ low COL and low taxes is the reason for its growth and success. But one of its most booming cities (which I happen to be a resident of) is Austin. Austin has high property taxes and a rapidly increasing COL.

It seems like Texas could be a great place for upper middle class and wealthy people, but I don’t think the miracle has applied to everyone or maybe even most. I would like to see how much the fracking boom has been responsible for the growth in “creative class” and other highly skilled jobs. I know a lot of the Fortune 500 companies in Texas are energy related and the legal sector has benefited from Oil and Gas in the state. I do think Texas has benefited from a growing tech scene and other highly skilled jobs but as I said I am still skeptical.

10. March 2014 at 01:42

The fact that there is no multiplier doesn’t dent Keynsianism one iota. To be more accurate, if there is no multiplier, that destroys the “balanced budget multiplier” idea, namely the idea that increasing taxes AND GOVERNMENT SPENDING by $X will raise employment. But no matter. That problem is easily solved by the simple expedient of not collecting taxes to cover the extra spending.

And as Keynes pointed out, there are two options there. The first is to cover the extra spending with borrowing. And the second is to not cover the spending at all, that is simply print new money to cover the spending.

In the latter case, even if the multiplier was less than one (e.g. if the ultimate addition to employment was half the INITIAL number of jobs created) I don’t see the problem. Indeed the latter “less than one” multiplier would occur where the private sector was being more thrifty than normal: i.e. saving a large chunk of the new base money created.

10. March 2014 at 05:17

Here is the Fed Reserve Bank of Dallas’ analysis:

“The oil and gas industry has been a driver of the Texas economy for the past 40 years. Its contribution declined with the oil-led recession of 1986 and appeared to slip further in the 1990s as the high-tech industry boomed. But oil and natural gas prices have risen since 1999, reaching record highs in 2008. This resurgence has boosted energy activity and factored into the recent economic recovery in Texas, affirming the industry’s long-held prominence in the state (Chart 1).

An econometric model developed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas documents the state’s evolving energy fortunes since the late 1990s. It shows that the industry is still contributing positively to Texas output and employment, though in a less-pronounced way than during the prior oil boom 30 years ago.”

****LINK****

http://dallasfed.org/research/swe/2011/swe1101g.cfm

10. March 2014 at 05:45

Brett, Morgan, Scott, Trumwell, Good points.

Travis, I added an update to address your point.

Jason, Yes, but when people talk about the Texas miracle, they refer to fast population growth, which has been going on for decades.

Ram, Yes, I noticed that too, I should have commented on it. When I read it I wondered how his current policy (at the time) was consistent with this approach. Certainly not at the October meeting.

Thanks Adam.

Ben, You said;

“but then people get down to business…”

Not sure where that analogy is going . . .

Steven, But how do you account with my data showing almost no correlation between Texas population growth and the health of the oil industry? I also wonder about your data. Oil production in Texas itself is soaring. Mexico is about to open up. There’s talk of fracking in other areas like Mississippi. How likely is it that oil employment in Houston falls sharply in the midst of a domestic production boom? You know more than me, but those numbers seem implausible.

Matt C, That may be true of Austin, but in most parts of Texas working class people are moving in because living standards are better than elsewhere.

Ralph, I agree this case is different from federal level fiscal stimulus. My point was different. The author simply assumed that the multiplier model applied, without even checking the population and unemployment data.

Matt, That points to another possible source of strength–high oil prices (pre-fracking). But even so, the population growth (which fell off after 2005), doesn’t show any multiplier effect.

10. March 2014 at 06:30

Wouldn’t it be easier to see a multiplier effect in North Dakota, where oil has had a large impact on a state with a small population an nothing else changing?

10. March 2014 at 09:59

“Steven, But how do you account with my data showing almost no correlation between Texas population growth and the health of the oil industry? I also wonder about your data. Oil production in Texas itself is soaring. Mexico is about to open up. There’s talk of fracking in other areas like Mississippi. How likely is it that oil employment in Houston falls sharply in the midst of a domestic production boom? You know more than me, but those numbers seem implausible.”

Have you actually been to Houston recently, Scott? It’s really a boom town. Lots of high end German and Italian metal on the streets there.

Now, you’re referring to the onshore, low capex segment; I was referring to the high capex offshore, Arctic and LNG segment. But let’s take Texas onshore anyway.

Production in Texas has been rising, primarily from the Eagle Ford (+43%), less so the Permian (+ a measly 8%), and falling in the Barnett (Dallas), and Haynesville (-27%, nat gas, East Texas into Louisiana).

Rig counts, per Baker Hughes, compared to same week two years ago:

– Barnett, -52% (-31 rigs)

– Eagle Ford, -9% (-22 rigs)

– Haynesville, -48% (-41 rigs)

– Permian, +3% (+17 rigs)

Not everything is rig counts, but a lot of services are linked to rigs. Production is growing well in the Eagle Ford, declining or unremarkable elsewhere in Texas.

Nor is this activity so profitable. Check out Baker Hughes Q4 presentation, and you’ll see that North America lost $0.08 per share, with total EPS down about 20 cents (-23%). Not such great times for North American service companies. Weatherford, another major service company, is laying off 7,000 people worldwide. So, as far as US onshore is concerned, there’s a bit more smoke than fire in the services and technologies area.

But I wasn’t referring primarily to the onshore segment.

10. March 2014 at 10:06

I was referring to the high capex segment primarily concerned with LNG, Arctic and deepwater projects. These are all well into the tens of billions of dollars for a single project. I adapt below a comment from Econbrower.

If you want to know about the situation of IOCs, see slides 40-50 of my Columbia presentation (link below). I would add this presentation really does seem to be the state of the art in oil markets theory, so if you’re a reader from the Fed, CBO or a major university, you could do worse that flip through the slides or actually watch what turns out to be a very fast-moving one hour presentation. It’s quite accessible and touches on pretty much everything you need to know about oil markets today.

I have consistently stated that there was an inflection point in the oil supply in 2005-it pretty much stalled out. And that’s still true. The legacy system of 2005-that is, excluding shale oil and oil sands-produces less today than it did in 2005. Jim Hamilton has also noted this.

If this is true, then we can make the case that the legacy system did indeed peak out in 2005. If it did, then we would expect a normal distribution around that peak, that is, the rate of departure from the peak should be the same as the approach to the peak.

But that didn’t happen. As you can see on slide 48, legacy oil production remained at levels much higher than expected by a normal distribution with a 2005 peak. Why? Well, because we threw a vast amount of money at the system, about $1.5 trillion more than we would have in the 1998-2005 period for a similar result. If we assume that a flowing million barrels of capacity costs $150 bn today, then that $1.5 trillion translates into about 10 mbpd of gross capacity, figure maybe 7-8 mbpd net of subsequent declines. (Deepwater, for example, can decline by as much as 25% in the early years of production.) And if you look at the graph, you see that actual legacy oil production was around 81 mbpd, when the expected would have been around 75 mbpd. Therefore, we can argue the case that all this extra investment did have a positive effect-it prevented the oil supply from declining faster than it would have otherwise.

Now, if you use supply-constrained forecasting (which I introduce in the beginning of the presentation), you could have forecast that we would see oil price resistance around $110 / barrel, which we have. Thus, the strategy of increasing capital intensity (investing more) due to higher oil prices-well, that strategy ran its course in 2011. Therefore, IOCs can-and now, could-no longer expect material oil price increases to save them from diminishing drilling and production opportunities.

But what of costs? If the normal curve concept is correct, then trying to maintain oil production at earlier levels becomes increasingly expensive. The natural decline floor falls away from peak oil production levels, and does so at an increasing pace. So, in a normal curve, as you depart the peak, the rate of decline increases at an increasing pace until you hit the inflection point somewhere halfway down the curve.

Thus, in attempting to hold earlier production levels, we would expect the IOCs to see increasing costs at an increasing pace. Is there any supporting evidence for this assertion? Let’s take a look at Shell’s opex (production and manufacturing expense) on a per barrel basis to see if this is true:

2008: $21

2009: $23

2010: $22

2011: $26

2012: $27

2013: $33

In just three years, Shell’s opex has risen by $11 per barrel, even as Brent oil prices have eased. I have earlier described Shell’s decision to suspend production guidance as “catastrophic”. This sort of dramatic deterioration in costs is truly catastrophic-and consistent with a model postulating a legacy peak around 2005.

I have earlier written about the collapse of capital efficiency at the oil majors, which is (nominally) one fifth of what it was in 2000 (slide 40). Thus, if we combine the collapse of capital efficiency with exponentially increasing opex, then we have a very, very ugly scenario before us. If we assume the oil majors develop their projects in order of economic attractiveness, that means most of the remaining oil projects in their portfolios are worse than the ones they’ve already developed-and they weren’t that great. How many of the remainder are viable at all?

In turn, this suggests we’ll be seeing falling capex from the majors; perhaps dramatically falling capex. We’re already beginning to see it pretty much across the board at the IOCs, just as I predicted more than a year ago.

Now, the way this plays out not only can be forecast, it can be calculated. If we accept the normal curve, then at best, the IOCs will be able to run parallel with the decline curve from here on out. But is that strategy profitable? It may be that the IOCs (and others affected by market economics, including the likes of Petronas and Pertamina) have to return to the natural decline curve. That would involve letting off something like 10 mbpd of production over the next, say, seven years. As it is, the IOCs production has been falling at a pace of 750 mbpd / year (2010-2012), and that was with massively increasing amounts of upstream spend. What will happen when capex is falling by 10% per year? In any event, I can tell you that there are virtually no degrees of freedom in how this plays out (leaving aside some sort of major improvement in technology or market access.) The outcome is not a forecast, it’s a calculation. (I haven’t worked through it yet.)

If I consider this from the policy perspective, then we have to consider how the aggregate oil supply might play out. US shales are considered to have maybe 2-3 more blowout years before peaking. Shale production is currently growing in excess of 1 mbpd / year; however, the EIA projects this growth to be only 600 kbpd in 2015 (which is still a fantastic number by any normal measure). By 2017, shale growth could be pretty minimal, perhaps 200 kbpd. Supply may also increase from the petro-exporters like Mexico and Venezuela. The pressures on them will surely cause them to open their markets. How much will this help, and when? And how much more can we expect from Saudi Arabia? If the answer to the latter two questions is “not much”, then there is the real prospect of the oil supply peaking out in absolute terms around 2017.

And then you (Scott), Menzie Chinn and Mark Sadowski better hope like hell that there’s no linkage between oil and GDP growth (slides 51-57), because if there is, the global economy is going to start seeing some real pressure around that time. That’s the policy concern.

So, that’s my view of IOC costs and their implications. And now you know something that Exxon, Chevron, BP and Citi don’t. They don’t use supply-constrained forecasting, so everything that is happening to them is a surprise. They don’t have this model. They don’t know why oil prices stalled out at recent levels. They don’t know why oil prices aren’t increasing. They don’t know why capex and production costs are increasing exponentially. They’re on the train, but they don’t know where it’s going or why.

To wit, here are a couple of quotes from CERA Week:

“We cannot continue to swallow this huge inflation,” said Christophe de Margerie, CEO of Paris-based Total. Lars Christian Bacher, executive vice president for development and production at Norwegian energy company Statoil, put it in existential terms. “The capital intensity of this industry is heading in a direction that’s not sustainable,” he said.

Indeed, over the last decade, global oil companies have increased capital spending more than 400 percent; production is up just 2 percent in that time, Bacher told the audience. Changing that equation, he said, “is a question of whether we will survive or not in the long-term.”

Indeed. That’s where we are today.

http://energypolicy.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/energy/Kopits%20-%20Oil%20and%20Economic%20Growth%20%28SIPA%2C%202014%29%20-%20Presentation%20Version%5B1%5D.pdf

http://energypolicy.columbia.edu/events-calendar/global-oil-market-forecasting-main-approaches-key-drivers

10. March 2014 at 10:14

This an excellent post! Although I am rarely surprised by liberal hubris, I was blown away by that extremely long article trying to debunk what we know to be true about the economy in Texas. Even liberal Texans cannot deny it. Well…some still do, but as the saying goes, we just tell ’em, “ohhh bless your little heart”, and dismiss their silly lib-tardedness out-right. All that said, even though the most recent population statistics may not be entirely due to the oil boom, in some places, like Midland/Odessa, the population growth is almost entirely due to it. To be quite honest, while the work is great and the money’s great, the congested-ness is miserable at the current juncture. Midland is a small city built for about 100,000 people and I do not doubt we have at least 200,000 running around these parts currently, with the boom. Not to mention the housing shortage and resultant price-gouging by crappy apartment complexes. Dah well…at least they’re finally building a bunch of new apartments now and the rents will come down some. So, to summarize, Texas is awesome and our economic policies generally kick ass, but housing shortages in boom towns are no bueno at all.

10. March 2014 at 11:19

Steven, You said;

“Have you actually been to Houston recently, Scott? It’s really a boom town. Lots of high end German and Italian metal on the streets there.”

I think you missed the point of the post. I never said the oil boom wasn’t creating income for Texas, I said it wasn’t creating any more jobs than they were creating before the oil boom. There are also lots of fancy cars in Silicon Valley, but little population growth. My post was about population growth. It’s slowing down in Texas. And yet the article claimed the fracking boom explains their high population growth.

I’ll defer to your expertise on Capex. As far as global oil production, I expect that to keep rising, albeit we may need higher prices for that to happen, or at least less political instability.

10. March 2014 at 12:27

Prof. Sumner, of all the things you have ever written on a blog, this has to be my all-time favorite paragraph:

This is 100%, absolutely true in my observation.

There is another explanation for the Texas miracle that will surely ruffle a few left-liberal feathers: Strange as it may sound, people like living in Texas! For those of us who choose to live here, we simply enjoy the Texas lifestyle. It’s not for everyone, but it is for me. That’s not explicitly a policy choice, it’s just a culture thing.

I chose to move to Texas. I could have chosen anywhere. I chose to live here. I wouldn’t have it any other way. It goes against the psychology of a lot of people to believe that Texas is a nice place for people who choose to live here, but still – we do like it here. 🙂

10. March 2014 at 14:54

Texas has always had low taxes and low living costs. It has not always had outstanding growth. Texas serves as its own internal control to refute the idea that its policies are the key to its RECENT economic growth. (I suppose one could make the argument that its policies are only important during different times and conditions, but those need to be laid out.) As others have noted, states with similar policies have not seen the same growth. I suspect there are multiple reasons for this surge over the last few years. My favorite is that the nation has finally discovered how good barbecue is there. That is certainly what I miss most about living there.

Steve

10. March 2014 at 15:18

It’s weird that Scott keeps confusing oil and fracking (natural gas), and for some reason places the oil boom in terms of production rather than prices. Scott, I know economists are sometimes more theoretical and less practical, but are you serious or just trolling? You know oil prices spiked around 2003 right? And that increasing production takes years. So that boom in your little graph shows the result of years of previous investment in old wells. Have I been trolled?

11. March 2014 at 08:26

Thanks RP.

Steve, Texas has been growing very fast for a long time, probably at least since AC was introduced in the 1950s.

Benny, If you are going to insult someone you ought not to make multiple stupid errors in one short paragraph. I am fully aware of the fact that fracking is used for both oil and gas. But you don’t seem to be.

The very high oil prices were around 2007-08, and population growth was already slowing by 2006. The upsurge in Texas oil drilling activity coincides with a slowdown in Texas population growth

Nice try.

11. March 2014 at 10:58

Scott –

I can tell you there has been significant employment related to oil field services and technologies. I could name a dozen people off the top of my head who’ve moved to Houston to be in the business. However, that’s anecdotal and Texas is a big state. I don’t know how the aggregates come out.

As for oil prices, here’s the way to think about them. Imagine you constrain the supply of a good, acting either as a monopolist or as a cartel. If I’m not mistaken, this would eventually take you to the monopoly price, MC=MR=P.

Now, here are the questions. Once the price is at the monopoly price, how fast can it increase from there? What are its drivers?

Further, if costs are increasing faster than the monopoly price, what happens to quantity supplied?

11. March 2014 at 11:02

Sorry, should be with MC=MR, with P at the point corresponding with that quantity on the demand curve.

12. March 2014 at 12:20

Steven, I think you misunderstood my claim. I absolutely agree that oil is creating lots of jobs in Texas. I was simply pointing out that there is no multiplier effect. Non-oil firms are less like to move to Texas today as the good engineers are snapped up by oil companies.

Regarding oil prices, some of the simple models talk about prices rising at the rate of interest. But when you add complexity to the model lots of different results are possible.