New and improved; it’s GDPplus!

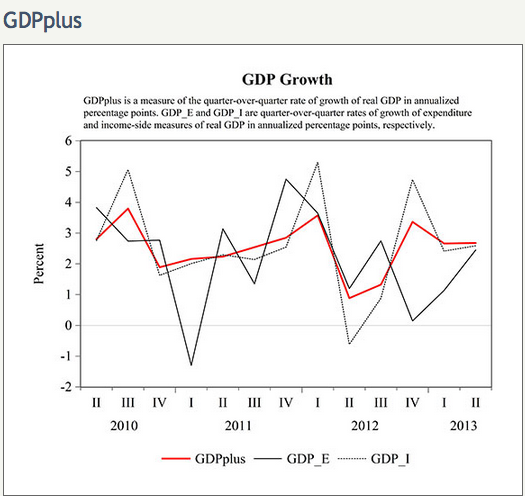

I’ve often complained about incompetence at the BEA. The quarterly GDP numbers don’t seem very accurate. For instance, they don’t seem to correlate with the jobs numbers, which seems really strange to me. The don’t correlate with GDI. Now the Philly Fed has done something about the problem. They have used the RGDI and RGDP estimates, as well as some fancy statistical analysis, to come up with optimal estimates of RGDP growth:

That’s what I thought all along!

Notice the RGDI numbers (dotted line) are better than the RGDP estimates (solid black line) in 11 out of 13 10 out of 13 cases. Also notice that growth has been pretty stable, except a slowdown in mid-2012, which led the Fed to adopt QE3 and forward guidance. Those numbers correlate with the monthly jobs figures, which show fairly steady growth, apart from a slowdown in mid-2012. And a zero fiscal multiplier in 2013.

Now we need NGDPplus estimates.

Many thanks to the Philly Fed, and can we all now use their figures?

Or at least until they produce estimates that don’t match my market monetarist priors? 🙂

Tags:

4. November 2013 at 14:27

Scott

I’m not sure how well the jobs numbers correlate with growth rates. They might correlate much better with GDPplus growth levels, but some back of the envelope math puts paid to the relationship you claim.

https://github.com/cmatjordan/GDPlus_comparison

4. November 2013 at 14:39

Not that it’s related to this article, but thought you might have a rebuttal for the following:

‘DID SCOTT SUMNER FIND MMT’S ACHILLES’ HEEL?’

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2013/11/scott-sumner-find-mmts-achilles-heel.html

Why is economics such a dismal science. Let’s call it ‘art’ instead.

4. November 2013 at 14:58

Randy Wray tries to go after Prof. Sumner in defense of MMT:

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2013/11/scott-sumner-find-mmts-achilles-heel.html

4. November 2013 at 15:08

CJ, There seems to be a problem with your link. What’s it supposed to show?

Warren, My rebuttal is that whoever wrote that nonsense is a liar, a moron, and a jerk, all wrapped up in one. Life’s too short to respond to someone who claims I asserted that lowering interest rates to zero would cause NGDP to double. (It’s got several names attached, so I don’t know who wrote it.)

Rates just fell to zero in 2008 and I don’t see NGDP doubling.

4. November 2013 at 17:19

” So let’s say they double the base and let rates go where ever they want. I claim this action doubles NGDP and nearly doubles the price level.”

It may be nonsense but this is where Wray is quoting from-he fails to attribute it.

http://diaryofarepublicanhater.blogspot.com/2013/11/sumner-on-achilles-heel-of-mmt.html

See also:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=10238

4. November 2013 at 17:21

The above quote is directly from you Scott. They aren’t from me or Wray

4. November 2013 at 17:35

It sure looks like in Quarter III, 2010, GDP_E is closer to GDPplus than is GDP_I. That makes GDP_I closer ten times out of thirteen, not eleven times.

4. November 2013 at 17:43

Mike, That quote says doubling the money supply causes NGDP to double, which is not a very controversial claim. The claim that cutting rates to zero causes NGDP to double is absurd.

Philo, My mistake, I’ll change it.

4. November 2013 at 17:51

Scott

It’s a repository where I dropped the excel file I used to do the math. If you click “view raw” here (https://github.com/cmatjordan/GDPlus_comparison/blob/master/GDP_comparisons.xls) it’ll ship you the file.

In summary, the GDPplus numbers have a rougly 25% correlation with new jobs numbers, but the BEA current-dollar and “real” GDP numbers correlate > 90%. Their GDP percent change based on current dollars has a 37% correlation with the new jobs numbers.

It’s probably a rates v levels thing, but your claim that the Philadelphia Fed’s numbers correlate well with new jobs numbers is untrue, as is the claim that the BEA’s numbers don’t correlate with new jobs numbers.

4. November 2013 at 18:48

The ABS has been using an averaging of Income, Production and Expenditure measures for some time.

http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Lookup/5206.0Explanatory%20Notes1Jun%202013?OpenDocument

4. November 2013 at 19:33

CJ, I’m 99% sure you’ve made a mistake somewhere. Just eyeball the data, the GDP plus numbers are obviously much better correlated with the jobs figures.

If you don’t think so, give me a link with some graphs, I can’t make heads or tails out of what you linked to.

Lorenzo, I’m not surprised you guys are ahead of us.

4. November 2013 at 20:06

With respect to the Randy Wray post, it appears that Mike Sax blogged on a post that Scott did on MMT over two years ago. Sax’s post was blogged about at Mike Norman’s, and in turn Wray blogged on the post at Mike Norman’s (i.e. up the food chain of Ancient Fiscal Tautology it went).

Other than the absurdity of Wray responding to something Scott wrote over two years ago, the most absurd thing is the importance that Wray attaches to Scott’s remarks on interest rates. MM obviously doesn’t think interest rates are an important measure of monetary policy.

So Wray’s argument that interest rates can have perverse effects on aggregate demand via the interest income channel (which is itself an incredibly implausible argument, unless you’re a bond coupon-clipping rentier like Warren Mosler who wonders how all the little poor people get by on their interest income when bond yields are so low) disproves Scott’s argument seems like an amazingly case of bidirectional obliqueness.

4. November 2013 at 20:56

Could someone please enlighten me about MMT?

Do MMTers view “monetary policy” as basically irrelevant? Do they see government spending and budget deficits as the main things driving employment?

Do MMTers oppose reducing the budget deficit during boom times?

4. November 2013 at 22:24

Travis, I think they believe the central bank can target and hit any real rate if interest it wants indefinitely and then use taxes to control the price level (which would otherwise be indeterminate).

Seems pretty wrong to me, but im not an economist.

4. November 2013 at 23:13

TravisV,

1. Yes. There are lots of places to read about MMT. I recommend Mosler’s site.

2. Ineffective for what it is being touted for, rather than irrelevant.

3. Yes.

4. No. MMT views the deficit as largely endogenous. During the boom, the deficit will go down all by itself. As the cycle begins to turn, as GDP levels off, and employment gains slow, before full employment and inflation have been reached, MMT advocates a fiscal stimulus to keep the economy and employment growing.

4. November 2013 at 23:24

TravisV,

1. Yes. There are lots of places to read about MMT. I recommend Mosler’s site.

2. Ineffective for what it is being touted for, rather than irrelevant.

3. Not in general, I think, but yes, as opposed to monetary policy. Employment is mostly driven by what happens in the private sector, which is 75% of the economy. Government is big, at 25%, and very much more easily manipulated, but it is the tail not the dog.

4. No. MMT views the deficit as largely endogenous. During the boom, the deficit will go down all by itself. As the cycle begins to turn, as GDP levels off, and employment gains slow, before full employment and inflation have been reached, MMT advocates a fiscal stimulus to keep the economy and employment growing. The size of the deficit per se is neither good nor bad, and is not a proper policy goal. Inflation and unemployment (or the size of the JG workforce) are the proper policy goals.

4. November 2013 at 23:54

ChargerCarl: Trying to work out what the MMTers believe makes my head hurt. For example, Wray writes in the above cited piece: Anyone who understands central banking knows that central banks have one tool in their tool kit, and it is not a Hammer. It is the overnight interest rate””the rate at which it lends to banks, and at which banks lend to each other against the safest collateral. That target, in turn, impacts other short rates on other very safe lending and on Treasury Bills. Most bets are off once we move beyond that, however. While I like your summary–it is clear–I am not sure it is correct.

Of course, anyone who says Anyone who understands central banking knows that central banks have one tool in their tool kit … It is the overnight interest rate””the rate at which it lends to banks, and at which banks lend to each other against the safest collateral. clearly does not understand central banking.

5. November 2013 at 00:33

Travis, I’ll do my best but it’s going to be hard to contain in this comment section. Also my understanding is far from complete, both of MMT and New Keynesian economics, so I apologise in advance for anything I get wrong on either side.

MMT is based around the theory of endogenous money. Endogenous money states that the central bank sets the cost of reserves (the FFR/Federal Funds Rate), banks then mark up these reserves (for profit and to cover risk) and then on-sell these marked up loans to any customers they can find that can afford them. Banks then are constrained by demand for loans from credit worthy customers (which the FFR affects, by lifting the cost of reserves), and by capital requirements, but **not** by their quantity of reserves. This is because well capitalised banks can acquire any reserves they need for a fixed cost thanks to money markets that are backstopped by the Fed. Boosting banking sector reserves then does nothing to increase loans unless it leads to a lower FFR.

This differs from conventional exogenous monetary theory/the money multiplier theory, which argues that banks are limited by reserves. That if you take out a loan and reserves are not increased, someone else in the economy will now no longer be able to afford a loan, and that conversely if the central bank injects new reserves this will lead to additional loans being made *even if* the FFR was unaffected (eg due to interest on reserves being paid).

There’s some overlap in the two theories at the zero lower bound, where it’s generally agreed that we’re limited by demand for loans and not by reserves (for excess reserves are aplenty). The difference is that MMT argues that we’re *always* limited by demand for loans, and that if we held the FFR positive via paying interest on reserves instead of draining liquidity via open market operations (how the Fed typically keeps the FFR above 0%), we’d see that.

The significance of all this? That governments may as well fund their deficits through “printing”, for with the monetary multiplier mechanism out of the picture it’d lead to all the same impact on prices as funding them through bond sales. That if you have a $1tn deficit to fund, it does not matter whether you fund it through the creation of $1tn worth of short-term bonds (which today, thanks to the ZLB will have $1tn on the face), the creation of $1tn worth of cash (which will also have $1tn on the face), or if you pull $1tn out of a safe where you stashed it during the last boom – the effect on prices would be the same all three ways, for they all increase the net financial assets of the non-government by *the exact same amount*. A full 1tn dollars.

So now with “government debt” out of the picture (it’s now simply dollars that have been spent into existence but not yet taxed away, eg non-government savings), we only need to worry on a year on year basis about whether the government’s deficit/surplus (how much it’s printing/destroying) is appropriate for the times. That is, the government can’t allow real resources such as workers to become scarce or it’d be a supply side inflationary pressure, but neither should the government allow the economy to become underemployed for that’d be wasteful. Unlike in conventional NK theory, the government would never be concerned about reducing a deficit merely because it’s a deficit, even in a boom time. Nor should the US government worry about trying to put aside USD in good times to spend USD in bad, as to MMT that’s quite irrelevant. Its capacity to do the former is not limited by the amount it has done the latter.

Anyway, that’s my take on it.

5. November 2013 at 01:28

Scott, any comments about 2007, which looks much weaker under the new measure?

5. November 2013 at 03:03

I don’t know what’s absurd about simply commenting on a 2 year old post-people are trotting out Krugman posts from years ago all the time-4 years, 6 years, 10 years, 15, if they think they’ve somehow caught him in an error. If you don’t believe me just check out Bob Murphy-most days he’ll have at least one old Krugman quote. We can’t discuss something Scott wrote 2 years ago?

In what way does he now disagree with what he wrote then? IF he doesn’t then where’s the problem?

I just wanted to write a Sumner-MMT post-it’s not my fault if he hasn’t written anything about them since.

The trouble with these schools-both MM and MMT is that they just want to stay in their own little ideological bubble and get daily affirmation of their views.

The important thing is Wray has now given me attribution.

I understand that in Scott’s thought experiment he talked about a doubling of the MG not a 5% cut in interest rates-I think maybe Wray is assuming the cut in rates would be an effect of doubling the MB-but that was in a healthy economy with no IRR.

What is the relevance to an economy like ours with IRR and that is far from healthy-even if improving somewhat?

We know that doubling the MB will have no such impact now as the Fed close to tripled it in 2008

5. November 2013 at 03:58

Hatzius: Fed will lower unemployment threshold http://www.businessinsider.com.au/hatzius-fed-will-lower-unemployment-threshold-to-6-percent-2013-11

5. November 2013 at 04:01

Lorenzo from Oz,

That quote either means (1) “the discount rate is the central bank’s only tool” or (2) “the (overnight) market rate is the central bank’s only tool”.

(1) is obviously wrong, but actually makes more sense than (2), since (a) the market rate is a target, not a tool; (b) central banks don’t have to target overnight rates; and (c) while many mainstream textbooks may suggest otherwise, it’s not even the case that this is the only possible target.

At least MMTers haven’t gone back to the old cost-push line that interest rate cuts were disinflationary, because interest rates are a cost of doing business.

5. November 2013 at 04:43

Quote below from the Fed paper from English’s via Lorenzo from Oz and Hatzius. Rough translation.

NGPDLT will work unless the Fed lacks credibility (i.e. is too cautious). Therefore we should be cautious in adopting NGDPLT because if we’re not cautious the policy will work but we need to be cautious that the risk of caution would make it incautious not to be cautious. Harrumph. I am bureaucrat and I’m OK. I sleep all night and I work all day.

“We then turned to additional questions regarding the monetary policy framework posed by the financial crisis and its aftermath. First we considered two possible departures from the current framework that have been discussed in the academic literature and in policy circles, namely, a permanent increase in the inflation target and a shift to a nominal income level target. We found that in our model these proposals could improve

economic outcomes if the change in framework is well understood by the public and is seen as credible. However, these are strong maintained hypotheses, and we noted that both proposals push very hard the assumptions of rational expectations, full credibility and absence of doubt about the model, in order to deliver their promised benefits. While there may be some

situations in which such changes would be appropriate, given that they involve significant communications challenges we argued that a cautious approach was appropriate, and that central banks should carefully consider the potential risks and costs of these approaches as well as their possible benefits. “

5. November 2013 at 04:55

Correction… credit due to Saturos not Lorenzo for the link to Fed paper via Hatzius.

5. November 2013 at 05:32

Mike, You said;

“We know that doubling the MB will have no such impact now as the Fed close to tripled it in 2008”

Well there you are! Printing money isn’t inflationary because the money supply has recently risen sharply without much inflation. Is that your argument?

Lorenzo and W. Peden, I guess that central banks cannot target exchange rates. Who knew?

5. November 2013 at 05:35

Thanks Saturos, That’s a step in the right direction, but 0% unemployment would be even better.

5. November 2013 at 05:51

Scott, you should read the Fed paper which prompted the Hatzius comments referred to by Saturos. Quite a lot about NGI targeting by an influential Fed Economist (William English, Director of the Monetary Affairs division and the Secretary and Economist of the FOMC).

5. November 2013 at 08:07

Alex,

In my opinion that’s a pretty accurate and succinct summary of MMT (but then I’m biased).

Alex:

“This differs from conventional exogenous monetary theory/the money multiplier theory, which argues that banks are limited by reserves. That if you take out a loan and reserves are not increased, someone else in the economy will now no longer be able to afford a loan, and that conversely if the central bank injects new reserves this will lead to additional loans being made *even if* the FFR was unaffected (eg due to interest on reserves being paid).”

This however is something that needs addressing. There is no such thing as “exogenous monetary theory/the money multiplier theory”. (There isn’t even an “exogenous money” Wikipedia page although if one is created you can be sure it will be written by MMT or Post Keynesians.)

Every Econ 102 textbook I’ve ever seen teaches the money multiplier is a function of three variables. The currency ratio is always portrayed as the depositors’ choice, the reserve ratio (above required, if any) is always the lenders’ choice, and the total amount of currency and reserves (the monetary base) is the central bank’s choice (even if supplied through the discount window), and all are dependent on the conduct of monetary policy by the central bank.

Every textbook that presents the simple model of multiple deposit creation follows this with a critique clearly stating its “serious deficiencies”. In Mishkin’s intermediate level textbook (I have the 7th edition), not only is there such a section, the chapter in which it is taught is followed by a whole other chapter that makes it abundantly clear that the currency and reserve ratios are variables.

All models are wrong, some are useful. The simple model of multiple deposit creation is useful. And there isn’t a single textbook I have seen that doesn’t point out its serious deficiencies. If students pass a course unaware of the simple model of multiple deposit creation’s serious deficiencies, that is the fault of the instructor, not the textbook.

So, in short, there is no such thing as “exogenous money” theory. The believers in endogenous money have carefully constructed an exogenous money strawman, complete with a series of erroneous beliefs and nonexistent defective textbooks, so that they could have something to verbally abuse and physically beat up in socially binding demonstrations of rage.

5. November 2013 at 08:35

John,

“MMT views the deficit as largely endogenous. During the boom, the deficit will go down all by itself. As the cycle begins to turn, as GDP levels off, and employment gains slow, before full employment and inflation have been reached, MMT advocates a fiscal stimulus to keep the economy and employment growing.”

I find this to be interesting because in recent conversations with Cullen Roche I pointed out that mainstream economics quantifies fiscal policy stance by changes in the cyclically adjusted budget balances. (Roche obviously represents Monetary Realism and not MMT, but clearly there is still a huge overlap of shared beliefs.) He argued that fiscal policy stance should be measured purely by the actual size of the fiscal balance. Thus what you say here seems to contradict what Roche was saying.

Do you have any sources to confirm this particular MMT view?

5. November 2013 at 09:36

SS,

“Life’s too short to respond to someone who claims I asserted that lowering interest rates to zero would cause NGDP to double.”

And yet you did say just that:

“So let’s say they double the base and let rates go where ever they want. I claim this action doubles NGDP and nearly doubles the price level.”

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=10238

Doubling the base and not paying IOR means dropping rates to zero.

I agree with you that this blog is full of moronic statements.

5. November 2013 at 09:37

My own take on MMT views concerning monetary policy is the following.

They portray the effects of monetary policy as occuring through only two channels: the Traditional Real Interest Rate Channel and the Bank Lending Channel. This leaves out seven other channels by Frederic Mishkin’s count: the Exchange Rate Channel, the Tobin Q Channel, the Wealth Effects Channel, the Balance Sheet Channel, the Cash Flow Channel, the Unanticipated Price Level Channel and the Household Liquidity Effects Channel.

Thus their argument that monetary policy doesn’t matter depends on showing that interest rates don’t have an effect on the economy and that the central bank has no effect on bank lending.

Recently I’ve noticed New Economic Perspectives blog author Dan Kervick repeating some version of the following question in response to any claim about the monetary base:

“What empirical evidence exists for that claim?”

I’ve done Granger causality tests on the monetary base over the period since December 2008 and find that the monetary base Granger causes the real broad dollar index, the S&P 500, the DJIA, commercial bank deposits, commercial bank loans and leases, the PCEPI, and 5-year inflation expectations as measured by TIPS.

The empirical fact that QE has an effect on the exchange rate of the dollar means that the Exchange Rate Channel is effective. (It’s always been curious to me how people can believe in the liquidity trap when Bulgaria, Denmark and Switzerland all successfully control their exchange rates despite being at the zero lower bound.) Does MMT address how exchange rates are set? (I honestly don’t know.)

The empirical fact that QE has an effect on stock prices (something which is obvious to nearly everybody) means that the Tobin Q Channel, the Wealth Effects Channel, the Balance Sheet Channel and the Household Liquidity Effects Channel are all effective. The usual MMT response is that “the markets are irrational”.

The empirical fact that QE has an effect on inflation expectations and the PCEPI means that the Unexpected Price Level Channel is effective. The effect on the PCEPI is not easy to observe, but most people acknowledge that QE has an effect on inflation expectations. Again the usual MMT response is that “the markets are irrational”.

The empirical fact that QE has an effect on commercial bank deposits, and loans and leases, means that the Bank Lending Channel is effective. This is particularly significant in debunking MMT (as well as Accomodative Endogeneity) since they claim that this is completely impossible.

But here’s by far biggest problem with Dan Kervick’s question.

I’ve read some of the research published by MMT economists such as Randy Wray (e.g. “System Dynamics of Interest Rate Effects on Aggregate Demand”). Mostly it consists of constructing stock-flow models using parameters derived from “neoclassical” economics estimates. I’ve never seen a single empirical MMT research paper, or even any evidence that they have any knowledge of econometrics at all.

What empirical evidence exists for MMT? None.

5. November 2013 at 09:55

Mark,

So what do you really think about MMT?

5. November 2013 at 10:08

Mark Sadowski,

You da man, thanks!

5. November 2013 at 10:16

dtoh,

“So what do you really think about MMT?”

They are an irritating source of misinformation much like the vulgar internet Austrians. The only difference is I’ve largely learned to ignore internet Austrians because almost everybody thinks they are cookoo. Unfortunately MMT is more plausible right now because of the large aggregate demand shortfall. Thus MMT/MR/PK still manages to get under my skin.

5. November 2013 at 10:57

OhMy,

“Doubling the base and not paying IOR means dropping rates to zero.”

To the contrary: a permanent doubling of the base would result in a huge rise in interest rates due to higher inflation expectations.

You’ve been on here long enough to know that Scott doesn’t think that loose money = low interest rates, yet I can’t imagine how else you could get “drop rates to zero” out of “double the base”. Therefore, he didn’t “just say that”; in fact, given what else Scott (rightly) believes about the relation between monetary policy and interest rates, he said precisely the opposite i.e. that interest rates would rise if base/NGDP/the price level roughly doubled.

5. November 2013 at 11:00

The correlation between interest rates and base money in an IOR-less economy:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/fredgraph.png?chart_type=scatter&id=FEDFUNDS,AMBSL&scale=Left,Bottom&range=Custom,Custom&cosd=1954-07-01,1954-07-01&coed=2007-10-01,2007-10-01&line_color=%230000ff,%23ff0000&link_values=true,true&line_style=Solid,Solid&mark_type=MARK_FILLEDCIRCLE,MARK_FILLEDCIRCLE&mw=4,4&lw=1,1&ost=-99999,-99999&oet=99999,99999&mma=0,0&fml=a,a&fq=Annual,Annual&fam=avg,avg&fgst=lin,lin&transformation=lin,pc1&vintage_date=2013-11-05,2013-11-05&revision_date=2013-11-05,2013-11-05

-and NGDP-

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/fredgraph.png?chart_type=scatter&id=FEDFUNDS,AMBSL_GDP&scale=Left,Bottom&range=Custom,Custom&cosd=1954-07-01,1954-07-01&coed=2007-10-01,2007-10-01&line_color=%230000ff,%23ff0000&link_values=true,true&line_style=Solid,Solid&mark_type=MARK_FILLEDCIRCLE,MARK_FILLEDCIRCLE&mw=4,4&lw=1,1&ost=-99999,-99999&oet=99999,99999&mma=0,0&fml=a,b&fq=Annual,Annual&fam=avg,avg&fgst=lin,lin&transformation=lin,pc1_pc1&vintage_date=2013-11-05,2013-11-05_2013-11-05&revision_date=2013-11-05,2013-11-05_2013-11-05

5. November 2013 at 11:20

Mark, could you send me a link to any empirical analyses of the kind you mention demonstrating causal relationships between either changes in the size of the monetary base or expectations of changes in the size of the monetary base, on the one hand, and other variables such as RGDP, NGDP, inflation, or inflation expectations. I really am interested in examining evidence of this kind. Most of what I read on all sides in the blogosphere doesn’t examine this kind of evidence, but instead argues a priori from conjecture and hypothesized first principles.

dkervick@comcast.net

5. November 2013 at 12:00

The only way that rates matter is by providing an economy-wide price window on creditworthy borrowing demand: it is epiphenomenon.

When rates decline, it is a symptom of a scarcity of creditworthy borrowers at a given level of NGDP. Hence, in the absence of vigorous borrowing, more base money is required (and supplied by the Fed) by (and to) the economy in order to collateralize/transact with less lending, and to produce and maintain low rates without widespread systemic bank default.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=o4A

Debt volume (debt/NGDP precisely) remains the key question: why should we care about reserve formation at the low-demand-for-borrowing zero bound? The banks need the reserves, to be sure, to produce and maintain a near-zero rate, and to insure against insolvency under a failing lending business model, but reserves do little for NGDP (other than form a reservoir of ultimate currency supply).

Currency demand ought to help boost NGDP at the zero bound, but the US has worked very hard to erect barriers to physical cash formation inside the US: hence, US currency moves abroad where it has higher utility outside of US banking regulations, and does not return.

So reserves are dead in an overleveraged — and hence zero-rate — economy, and NGDP has weights attached to its feet from physical currency regulatory restrictions. De-regulate currency use in the US, and you will see an NGDP explosion.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=o4F

5. November 2013 at 12:03

dtoh, I’d still like to understand what happens if the Fed were to revalue gold to $1300/oz (it is on their balance sheet, after all, and the ECB marks-to-market). Their liabilities (reserves, currency) increase, right? Net financial assets….

5. November 2013 at 12:10

Dan,

I sent you an email with Word document containing the results of the seven Granger causality tests I mentioned above.

5. November 2013 at 12:50

jknarr,

Sorry I don’t understand the question.

5. November 2013 at 12:54

dtoh, What are their most interesting observations? (as it’s unlikely I’ll have time to read it.)

OhMy, Might I suggest a course in logic? You know full well that monetarists don’t think easy money means low rates. If you think it means low rates that’s fine, but don’t lie and claim that I agree with you.

BTW, people in Argentina and Brazil will be amused by this claim:

“Doubling the base and not paying IOR means dropping rates to zero.”

As their monetary base doubled every 15 months between 1960 and 1990. I don’t recall zero interest rates in either country.

In case you’ve never taken logic, let me spell it out for you:

If I think A implies C but not B, and you think A implies B, then it is not accurate to claim that I think B implies C. Is that too hard for you? If so, trying taking a course in logic.

5. November 2013 at 13:00

Scott,

The conclusion with respect to NGILT is:

“We then turned to additional questions regarding the monetary policy framework posed by the financial crisis and its aftermath. First we considered two possible departures from the current framework that have been discussed in the academic literature and in policy circles, namely, a permanent increase in the inflation target and a shift to a nominal income level target. We found that in our model these proposals could improve

economic outcomes if the change in framework is well understood by the public and is seen as credible. However, these are strong maintained hypotheses, and we noted that both proposals push very hard the assumptions of rational expectations, full credibility and absence of doubt about the model, in order to deliver their promised benefits. While there may be some

situations in which such changes would be appropriate, given that they involve significant communications challenges we argued that a cautious approach was appropriate, and that central banks should carefully consider the potential risks and costs of these approaches as well as their possible benefits. “

So to restate my earlier post, they basically say,

NGILT will work unless the Fed lacks credibility (i.e. is too cautious). Therefore we should be cautious in adopting NGILT because if we’re not cautious the policy will work but we need to be cautious that the risk of caution would make it incautious not to be cautious.

5. November 2013 at 13:43

dtoh, Very well said!!

5. November 2013 at 14:39

Mark – You said, “in short, there is no such thing as “exogenous money” theory.”

Can you (or anyone) explain how the loanable funds theory of interest is compatible with endogenous money?

5. November 2013 at 16:28

Jared,

“Can you (or anyone) explain how the loanable funds theory of interest is compatible with endogenous money?”

It’s not. The stock MMT explanation goes something like this:

“Banks do not make loans based on loanable funds but based on demand, profitability, and the capital they hold.”

Of course, how that is compatible with the fact that central banks usually target the overnight rate by using open market operations to adjust the supply of reserve balances remains something of a mystery.

5. November 2013 at 18:08

GDP plus numbers correlate with job numbers because the unemployment rate is an explicit input into the model. I am not sure why the authors thought it was appropriate to exclude that from the abstract, buts its there in the fancy statistics. Not to say the measure is not an improvement, only to say that the correlation is not reinforcing evidence of its efficacy.

5. November 2013 at 19:21

Andrew, Thanks for clarifying that.

5. November 2013 at 19:30

Well, what does it mean to say that the MB ‘granger caused’ this list of other variables?

Granger causality isn’t necessarily real causality is it? As for empirical evidence we do have proof that the Fed almost tripled the MB in 2008 and this didn’t increase either inflation or NGDP. In fact both dropped precipitously soon after.

5. November 2013 at 19:33

Well, what does it mean to say that the MB ‘granger caused’ this list of other variables?

Granger causality isn’t necessarily real causality is it? As for empirical evidence we do have proof that the Fed almost tripled the MB in 2008 and this didn’t increase either inflation or NGDP. In fact both dropped precipitously soon after.

5. November 2013 at 19:33

Well, what does it mean to say that the MB ‘granger caused’ this list of other variables?

Granger causality isn’t necessarily real causality is it? As for empirical evidence we do have proof that the Fed almost tripled the MB in 2008 and this didn’t increase either inflation or NGDP. In fact both dropped precipitously soon after.

5. November 2013 at 19:50

Mike:

“As for empirical evidence we do have proof that the Fed almost tripled the MB in 2008 and this didn’t increase either inflation or NGDP. In fact both dropped precipitously soon after.”

It is an empirical regularity that monetary changes bring about effects with a time lag. You are setting an arbitrary cut off time limit when you say “soon after.”

If we take into account this time lag, then the tremendous increase in the monetary base in 2008, and higher inflation and NGDP, are in fact positively correlated.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=o5Q

That huge uptick in CPI and NGDP past 2009 is not only positively correlated with a lagged change in the monetary base, but theory suggests that an increase in the money supply should, ceteris paribus, bring about higher prices and spending.

A missing link is how much of the shadow banking market experienced credit deflation alongside the increase in the monetary base. In other words, what happened to the total money supply. The Fed no longer tracks it, but by private estimates, the total money supply shrank in 2008, but then significantly grew thereafter. This is consistent with the CPI and NGDP outcomes.

5. November 2013 at 19:51

Mark,

“Of course, how that is compatible with the fact that central banks usually target the overnight rate by using open market operations to adjust the supply of reserve balances remains something of a mystery.”

MMT has no qualms about that. If you drain liquidity to push up the cost of reserves banks are still going to add on their markups but now interest rates in the economy are going to be higher. That reduces demand for loans, as there’s fewer customers that can afford the higher rates.

Some proponents will argue that the effect of this will be muddied by the fact that savers will now be receiving more income, but on the whole I think few in the MMT world would be surprised that pushing up the risk-free rate has an effect on demand for loans, particularly in the short-term.

What MMT would argue is that you could achieve the exact same effect through simply paying interest on reserves (a floor on the FFR) and offering discount window lending (a ceiling on the FFR). Under this system it’s clear that a positive risk-free rate is a simple government subsidy on savings, that there’s a simple levy applied to borrowed money, and that money is entirely endogenous. Here MMTers argue that you’d see much the same loaning and effects on demand as we do today just now with the excess reserves Keynesians would normally associate with a liquidity trap.

I would be very interested to know what market monetarists believe would be the consequence of adjusting rates through varying the floor/ceiling offered by interest on reserves and the discount window respectively rather than through OMOs. I honestly have no idea, as under that system money is clearly endogenous – no two ways about it. What would be the consequences of this?

6. November 2013 at 00:24

Geoff I guess it depends who you ask, Sumner says monetary policy works with ‘veritable leads’ not lags.

We haven’t had much inflation to speak of since anyway-it’ just over 1% now.

6. November 2013 at 01:57

That Fed paper by English et al is interesting. Encouraging that they are thinking, and have lots of discussion about Woodford. Not much on your key point, the key point, about the real,effects of nominally sticky wages. And it is really poor how they still get confused about the issue of data revisions to nominal income, p.30-32 and the chart Figure 12 at the back. Not for a moment do they worry about RGDP revisions or targeting something as will-o’-the-wisp as CPI.

http://www.imf.org/external/np/res/seminars/2013/arc/pdf/english.pdf

6. November 2013 at 02:07

And it’s only revisions to nominal income levels they talk about. Growth rates are what matter, and especially expectations of growth rates. On reflection, they are missing something important, I fear.

6. November 2013 at 06:56

James, Actually I prefer level targeting, remember that doesn’t mean keeping NGDP level, but rather returning to the growth path if you deviate from it.

6. November 2013 at 07:48

Alex,

“…Under this system it’s clear that a positive risk-free rate is a simple government subsidy on savings, that there’s a simple levy applied to borrowed money, and that money is entirely endogenous…I would be very interested to know what market monetarists believe would be the consequence of adjusting rates through varying the floor/ceiling offered by interest on reserves and the discount window respectively rather than through OMOs. I honestly have no idea, as under that system money is clearly endogenous – no two ways about it…”

In my earlier response to Jared I didn’t mean to suggest that money endogeneity necessarily implies loanable funds theory is inapplicable. I only was trying express, as best as I can, what MMT believes about loanable funds.

In its simplest terms, what does endogenous money really mean? It means that monetary aggregates are dependent variables and not independent variables.

Money endogeneity is usually taken by enthusiasists of the concept to mean that monetary policy is ineffective. However money may or may not be endogenous depending on what the central bank is targeting. Usually central banks target inflation meaning that both narrow and broad money would be endogenous. Right now, in the US, QE necessarily means that narrow money, and to a large extent, broad money, are not endogenous.

Now, what does this mean in terms of the implications of a channel system of interest rates for the endogeneity of money? None that I can see. In particular, all central banks that have a channel system still target overnight rates through open market operations, so I don’t see why it should matter in that respect.

6. November 2013 at 08:07

Mike Sax,

“Well, what does it mean to say that the MB ‘granger caused’ this list of other variables?”

To say that the monetary base Granger causes X is to say that the monetary base provides statistically significant information about future values of X.

“Granger causality isn’t necessarily real causality is it?”

Of course not. By definition there is no statistical procedure that can show metaphysical causality.

“As for empirical evidence we do have proof that the Fed almost tripled the MB in 2008 and this didn’t increase either inflation or NGDP. In fact both dropped precipitously soon after.”

The increase in the monetary base in after September 15, 2008 was in response to the financial crisis which essentially was the result of the accelerating declines in the rates of increase in NGDP which started all the way back in 2006. And in fact the acceleration in the decline in NGDP came to a halt the very quarter that the monetary base first saw large scale increases.

Incidentally NGDP is cointegrated with the monetary base and there is bidirectional Granger causality between the two variables on quarterly data going back to 1947.

6. November 2013 at 08:41

Scott

That paper criticises level targeting by saying the revisions to the levels mean you never know where you really are, so policy responses could be very wrong at any one time base on first cuts of data. Of course, 3Q 2008 data was pretty unambiguous to a central bank using the right gauge for monetary policy.

6. November 2013 at 14:13

Mark – Thanks for your response, but I wasn’t asking what MMT thinks about loanable funds. I was trying to assess what theory of money YOU thought was compatible with loanable funds. In your answer to me above, you seemed to assert that loanable funds implies a denial of endogenous money. So MMT is not arguing against a straw man when they scream “loans create deposits (unconstrained by reserves)”; they’re arguing against the very real proponents of loanable funds, of which there are many. Do you believe loanable funds can be made consistent with an endogenous theory of money?

You also said “However money may or may not be endogenous depending on what the central bank is targeting. Usually central banks target inflation meaning that both narrow and broad money would be endogenous. Right now, in the US, QE necessarily means that narrow money, and to a large extent, broad money, are not endogenous”.

Even with QE, the central bank is targeting an interest rate, as they always do. Their current target is 0 – 0.25, to which market participants have responding by selling bonds and holding more money. But what do you think would happen if the Fed continued their asset purchases, and announced they would be ongoing until at least year-end 2015, but raised IOR to 2.25 immediately? I’m betting we’d see a decline in money aggregates despite the increase in the base, because market participants would respond to the increased rates.

6. November 2013 at 14:14

That’s why the key to the whole thing is to have a NGDP futures market, so that the Fed can target a quality, moving estimate. Without futures, using NGDP targetting is still driving using only the rear view mirrors.

6. November 2013 at 15:27

@Mike Sax

As for empirical evidence we do have proof that the Fed almost tripled the MB in 2008 and this didn’t increase either inflation or NGDP

This is just absolutely factually false.

(How does this urban legend live on?)

In July 2008 a deflationary plunge began and rapidly accelerated to a 13% annual rate (Q over Q). This was the first deflation since the 1950s and matched the *worst* deflation of the start of the Great Depression itself.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=nLE

Then, to stop it, the Fed hit the market with QE1 in November and the deflation reversed itself on the proverbial dime at the start of 2009 — with corresponding impact on NGDP — exactly as Friedmanite monetary policy predicts.

Since then I can’t count how many MMTers, among others, have told me “The Fed can’t do anything, just look at all they did in 2008 and how they got no result at all.”

In response, I’ve frequently pointed out what really happened and asked, “If the Fed is so impotent, how do you explain that? Remarkable coincidence?”

To which the “others” have often replied “Oh, I didn’t know that”. But no MMTer has ever given me any answer at all.

6. November 2013 at 16:01

Jared,

“In your answer to me above, you seemed to assert that loanable funds implies a denial of endogenous money.”

Endogenous money, in the sense that monetary aggregates can be dependent variables depending on how the central bank chooses to conduct monetary policy, is not at all irreconcilable with loanable funds theory.

“So MMT is not arguing against a straw man when they scream “loans create deposits (unconstrained by reserves)”; they’re arguing against the very real proponents of loanable funds, of which there are many.”

Yes, because it is only half right.

“Do you believe loanable funds can be made consistent with an endogenous theory of money?”

It is consistent with endogenous money as I defined it above.

In other words, is bank lending determined by the amount of deposits in banks, or is the amount deposited in banks determined by the amount of lending? The answer is that it is a simultaneous system. Financial prices adjust to make those amounts consistent with each other.

“Even with QE, the central bank is targeting an interest rate, as they always do. Their current target is 0 – 0.25, to which market participants have responding by selling bonds and holding more money.”

It’s true that there is still a fed funds target range, but the Fed doesn’t need to do much right now to hit that target. In fact there have been lengthy periods of time when the Fed has done no open market operations at all since setting that target.

“But what do you think would happen if the Fed continued their asset purchases, and announced they would be ongoing until at least year-end 2015, but raised IOR to 2.25 immediately? I’m betting we’d see a decline in money aggregates despite the increase in the base, because market participants would respond to the increased rates.”

This is probably true. One of the advantages of interest on reserves is that the central bank can set the amount of reserves independently from the policy rate. In fact Sweden was able to set the policy rate at a relatively high level in the mid-1990s despite a greatly enlarged monetary base in response to their financial crisis.

7. November 2013 at 06:48

You appear to be holding two contradictory positions Mark?

Jared,

Can you (or anyone) explain how the loanable funds theory of interest is compatible with endogenous money?

Mark,

It’s not.

Jared,

Thanks for your response, but I wasn’t asking what MMT thinks about loanable funds. I was trying to assess what theory of money YOU thought was compatible with loanable funds. In your answer to me above, you seemed to assert that loanable funds implies a denial of endogenous money.

Mark,

Endogenous money, in the sense that monetary aggregates can be dependent variables depending on how the central bank chooses to conduct monetary policy, is not at all irreconcilable with loanable funds theory.

Which answer contains the typo?

7. November 2013 at 09:11

NicTheNer,

The first answer refers to the MMT position. The second answer refers to my opinion.

This should be crystal clear if you read the entire exchange.

7. November 2013 at 13:43

So according to MMT “loanable funds” is not compatible with “endogenous money”. But according to you “endogenous money” is compatible with loanable funds?

Could you explain the difference in the reasoning to reach each conclusion?

It seems you are saying that its possible for the central bank to target broad money under some targeting regime?

Mark –

“However money may or may not be endogenous depending on what the central bank is targeting. Usually central banks target inflation meaning that both narrow and broad money would be endogenous. Right now, in the US, QE necessarily means that narrow money, and to a large extent, broad money, are not endogenous”

What has changed about commercial bank practise which means they no longer have as much discretion about their own level of broad money creation? Would this imply that the central bank can cause them to lend more if it wanted to do so?

It seems that if they didn’t need reserves to lend prior to QE policy (which is consistent with endogenous money), and so having surplus reserves with QE doesn’t provide any more/less discretion to them. So money is still endogenous, exactly as it was before. What don’t I understand about this?

7. November 2013 at 17:02

NicTheNer,

“So according to MMT “loanable funds” is not compatible with “endogenous money”.”

Well, let me put it this way. MMT believes money is always endogenous, and they object to loanable funds theory.

“But according to you “endogenous money” is compatible with loanable funds?”

Yes.

“Could you explain the difference in the reasoning to reach each conclusion?”

I have never really understood MMT’s objection to a non-naive version of loanable funds theory well enough to explain it in a manner that would probably do it justice. In short it makes no sense to me.

“It seems you are saying that its possible for the central bank to target broad money under some targeting regime?”

It might be possible, but I can’t imagine why the central bank would want to do that.

“What has changed about commercial bank practise which means they no longer have as much discretion about their own level of broad money creation?”

The creation of broad money by commercial banks is always endogenous to the central bank’s conduct of monetary policy. What has changed is that broad money creation is no longer itself entirely endogenous to that conduct. QE results in the direct creation of commercial bank deposits, and to the extent that this is true, broad money is not currently entirely endogenous.

“Would this imply that the central bank can cause them to lend more if it wanted to do so?”

The fact that QE directly creates commercial bank deposits doesn’t necessarily imply this will result in increased bank lending. However, I’ll say more on this in a moment.

“It seems that if they didn’t need reserves to lend prior to QE policy (which is consistent with endogenous money), and so having surplus reserves with QE doesn’t provide any more/less discretion to them. So money is still endogenous, exactly as it was before. What don’t I understand about this?”

A good summary of the main schools of Post Keynesian empirical endogenous money research can be found in Table 1 of this paper (sorry no free copy):

http://ideas.repec.org/a/mes/postke/v25y2003i4p599-611.html

Much of this research involves the use of Granger causality on monetary aggregates and loans.

If I had to identify the different schools of endogenous money with a particular economist I would say Accomodative Endogeneity is represented by Basil Moore, Structural Endogeneity by Robert Pollin and Thomas Palley, and Liquidity Preference by Peter Howell.

Accommodative Endogeneity theorizes that loans cause base money, and that loans cause broad money, but base money does not cause loans, and broad money does not cause loans. Structural Endogeneity theorizes that the causality is bidirectional in each case. Liquidity Preference focuses purely on the relationship between loans and broad money, and theorizes that the causality is bidirectional.

I’ve conducted extensive Granger causality tests on the US QEs using a technique developed by Toda and Yamamato that in my opinion conclusively refutes the idea that QE has no effect on broad money and bank lending. What I find is that since December 2008 the monetary base Granger causes loans and leases at commercial banks and that the M1, M2 and MZM money multiplier all Granger cause loans and leases (but neither is the other way around). This is precisely the opposite of what Accomodative Endogeneity predicts.

7. November 2013 at 19:07

James, I think any policy suffers when you don’t know where you are. Or should I say any good policy. You can peg gold prices and always know where you are. But any sort of dual mandate approach suffers from uncertainty about the current level of prices and output. I do think the Philly Fed’s new GDP data will prove to be far more robust–they should have done this long ago.

18. February 2017 at 07:38

[…] The claim that cutting rates to zero causes NGDP to double is absurd.” http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=24551#comment-290539 Of course, I’m kind of ticked at Wray too-he didn’t give me […]

17. March 2017 at 04:41

[…] econometrics at all. What empirical evidence exists for MMT? None.” http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=24551#comments Dan Kervick seemed rather impressed by this awesome display of wonkishness: […]