Never reason from a quantity change

The jobs number for February (20,000 jobs) was quite weak. It might just be a one-month blip—the moving average of job creation is still pretty good—but let’s suppose it’s real. What does that mean?

It might mean there is not much demand for workers. Or it might mean there is not much supply of workers. How can we tell? One place to start is with wage numbers. Less demand for workers results in lower wages, while less supply of workers results in higher wages. (Supply and demand. You won’t get this sort of PhD-level sophistication in MMT blogs!)

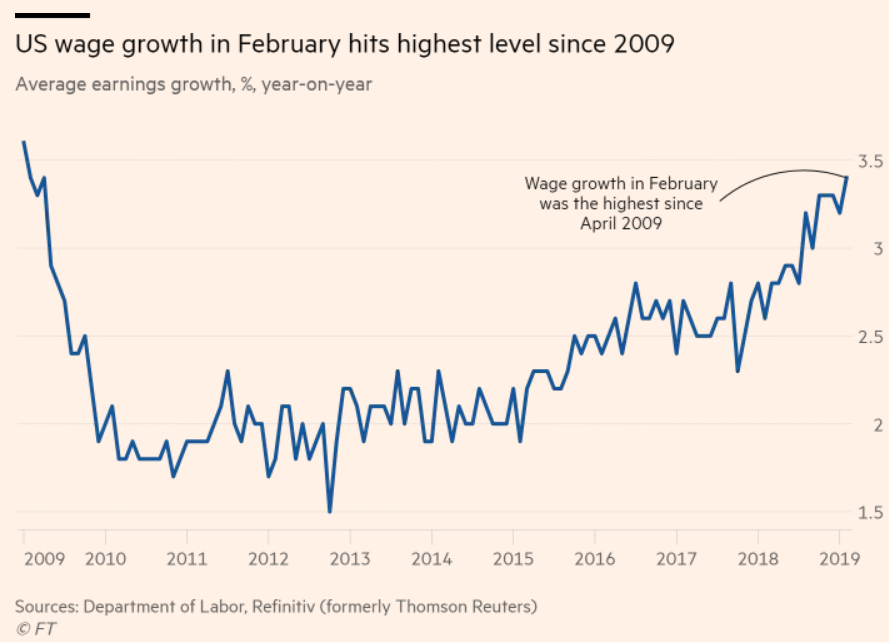

Here’s the FT:

Wage growth is up to 3.4%, the highest since 2009. As wage growth continues to accelerate, I’m becoming less concerned about the “lowflation” issue.

Just to be clear, I’m not saying that wage growth is driven by a reduced supply of workers—it’s very possible that February’s jobs number was just a blip and strong jobs growth will continue in 2019. What I am saying is that if we are in a new era of slower jobs growth then lower supply is the most likely culprit.

Don’t reason from a price change and don’t reason from a quantity change.

Reason from a P&Q change.

PS. FWIW, the FT suggests that February may not be a blip:

Data out over the past month have added to the view US economic growth may be cooling. Both industrial production and retail sales surprised on the downside in January and in December respectively. The housing sector meanwhile had a lacklustre end to 2018, with housing starts falling to their lowest level in more than two years in December while home price growth decelerated. . . .

In a sign of the economic uncertainty, Goldman Sachs said this week its rolling forecast for first-quarter US economic gross domestic product was pointing to growth at an annualised rate of just 0.9 per cent. A separate ‘tracking estimate’ from the Atlanta Fed forecasts growth at a rate of 0.3 per cent.

Soft landings have never been easy. This would be America’s first ever.

But if the Aussies and Brits can do it . . .

Tags:

8. March 2019 at 08:32

Very good. Had your profession paid more attention to wage growth, you would not have been as surprised at the continued strong job growth over the past couple years.

21 million private sector jobs in 9 years! The death of the American jobs machine has been greatly exaggerated.

Anyway, yes, it would appear we have reached something like full employment. Yay America.

Along with the strongest wage growth since the recession, we are witnessing a decline in corporate earnings, which surged in early 2018.

Here’s a theory: companies banked the corporate tax cut initially, but are now forced to share with employees due to the tightest labor market this century.

All in all, definitely looking like a soft landing.

8. March 2019 at 08:48

Brian, Speaking of full employment, the quality of workers in service industries is deteriorating rapidly. Service sucks. They are hiring anyone who can fog a mirror.

8. March 2019 at 09:21

Scott, maybe that’s just part of the SoCal experience…

Enjoy the sunshine.

8. March 2019 at 11:58

Brian, No, I also see it when I travel. Businesses almost everywhere are short of employees, and the people they hire are getting worse. I just visited Tucson, and the hotel was a disaster.

8. March 2019 at 12:18

Fair enough. And I understand the aggravation.

Of course, this does sound a bit like the old aristocratic lament that good help is so hard to find nowadays.

In other words, bad news for you and me, but good news for the low-skilled.

8. March 2019 at 13:00

Brian, You said:

“Of course, this does sound a bit like the old aristocratic lament that good help is so hard to find nowadays.”

It’s not a little bit like that old lament, it’s exactly like it.

8. March 2019 at 13:20

Scott,

But didn’t you just say,

“Monetary policy causes changes in inflation, not S&D imbalances.”

8. March 2019 at 13:48

Tight labor supply in services may look inflationary. But the fact that labor is tight in less productive work is only a side effect of many potential workers having moved to more productive sectors. I think there is a parts of the elephant problem here, and the parts that look inflationary are always the more basic, mature parts that are more visible in real time.

8. March 2019 at 14:42

Brian, Speaking of full employment, the quality of workers in service industries is deteriorating rapidly. Service sucks. They are hiring anyone who can fog a mirror.

Yes and that is good news. I bet a $15 minimum wage would greatly improve service in fast-food restaurants and that would be bad news.

8. March 2019 at 14:57

Of course, that US immigration policies have greatly increased the number of workers who are high school drop outs has no effect.

https://www.nber.org/data-appendix/w25577/Binder_Bound_maleLFP_appendix_revisionFinal.pdf

Just as Australia has a MUCH higher rate of immigration, and the service is fine …

(Any opportunity to point and laugh at US immigration mismanagement.)

8. March 2019 at 16:57

dtoh, Yes, I did. And I still say that. This post does not discuss supply and demand imbalances.

Floccina, I agree.

Lorenzo, i agree that it would sense for the US to take in more high skilled immigrants, but the bad service is not (mostly) coming from immigrant workers, it’s mostly coming from not enough workers, and to some extent from poor quality workers.

8. March 2019 at 17:25

I hope labor markets get “tighter” for several generations.

A good sign would be if most restaurants convert to buffet-style service, or box lunches, or other mechanisms you see in fast-food restaurants.

By the way, unit labor costs are increasing at about a 1% annual rate, and wages remain a drag on the general inflation rate and on the Fed’s 2% inflation target. A healthy development for the United States would be real and solid wage growth for the next 10 to 20 years. Could the 1950s and 1960s happen again?

It now looks like the Fed overtightened in 2018 and we may see a recession in 2019. It also appears that the ECB may have recently reduced monetary stimulus to negative effect and they may also have a recession in 2019. And the Bank of Japan may not have moved to enough monetary stimulus in the last couple years.

Gee, do you see a pattern here?

Can you leave central banking to central bankers?

8. March 2019 at 17:44

Add on: or is the answer to central bank and ineffectiveness not in central bankers but in their lack of tools? That is, until recently they were trained to think about interest rates.

Then with the Great Recession of 2008, central bankers began to think about interest rates and quantitative easing. But perhaps QE is like using a pair of scissors to cut through the jungle.

In 2003, such a sober minded individual as Ben Bernanke suggested money-financed fiscal programs.

I think the general public and then later orthodox macroeconomists will come to accept money-financed fiscal programs. Or socialism.

In the latter case, expect low-quality service in restaurants and hotels for a very long time.

8. March 2019 at 19:16

Add on, add on (sorry): Though it is a bit outside the ken of macroeconomics, there is a partial “solution” to labor “shortages”

The US sits on top of a pool of un-utilized labor, mostly youthful and agile.

College students.

Of course, this would call for some changes in the way labor is viewed, and in credentialism, and in academia.

But really, could there not be four-year undergraduate law and business programs, and we could dispense with the law schools and MBA programs, replaced by working apprentice positions upon under-graduation?

And if wages rise enough, more students will forego college altogether, and perhaps we could make that a wise choice. The community colleges and the vocational training is a good idea. A peep at modern-day four-year college curriculums is enough to dissuade anybody from advocating more college education.

The secret is higher wages. And, in Boston. NYC and the West Coast, lower housing costs (end property zoning).

There is no such thing as a “worker shortages” (as the Fed puts it in their Beige Books). There is only supply and demand, and where the lines cross.

Keep demand high and higher, and figure out how to develop supply.

8. March 2019 at 20:46

Scott,

First you said, “Less demand for workers results in lower wages, while less supply of workers results in higher wages.”

Then you said, “This post does not discuss supply and demand imbalances.”

Unless this is MMT-speak, you have totally lost me. Could you elaborate.

8. March 2019 at 20:52

@Benjamin Cole

Two logic issues…

One – Fed incompetence does not imply that politicians are competent.

Two – “I think the general public and then later orthodox macroeconomists will come to accept money-financed fiscal programs. Or socialism.” Fiscal programs are socialism. It’s not an OR condition.

8. March 2019 at 22:23

Benjamin,

Today, outside the zero-bound, the Fed has COMPLETE control over NGDP. The Fed simply lowers IOR and/or purchases Treasuries.

In 2007-08, the Fed may have indeed hit a bound with purely using open market purchases. This is where I disagree with Scott about the power of expectations and purchases of Treasuries. If the Fed had no discount window and did no Section 13(3) programs, the zero-bound would have been hit probably in 2007. The zero-bound definitely would have been hit in March 2008, with the bankruptcy of Bear Stearns followed quickly by bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers.

Personally, I have an extremely strong belief in absolutely no government backing of private financial institutions. Eliminating the discount window and deposit insurance is an absolute moral imperative. Their very existence is an institutionalized form of stealing from the poor at gunpoint and giving to the rich.

Without discount window or deposit insurance, the financial industry should see 100% reserve accounts as the only truly safe form of demand deposits. Based on monetary aggregates, these 100% reserve accounts may sometimes be higher than the quantity (total debt held by the public) + (monetary base). So a helicopter money backdoor of tax cuts should exist as a tool to meet NGDP targets.

9. March 2019 at 01:21

dtoh:

Hello, and thanks for your comments.

1. Yes, elected officials may, or may not be, less competent than central bankers. But elected officials seek re-election (well, except at end of career when they seek Fat City in lobby-land). If inflation is too high, or unemployment too high, they stand a fair chance of getting the boot.

Besides which, I prefer simplicity and transparency in government. If I feel money policy is too tight or loose, I want vote to vote accordingly. Under the present system, the mechanism of democracy in monetary policy is Rube Goldbergian at best, and at all levels.

1a. Okay, Trump is a boor, the vulgarian talk-show host who became President of the United States. A liar! A grifter! Yet, Trump has been right on monetary policy, and the Fed wrong. There is something that goes awry when “experts” get in charge of government policy. When even Trump is better than the experts…maybe we need to re-consider how things are done.

2. Yes, you are right that government spending is socialism, and even communism (in the case of the US defense establishment and VA systems). But I do not advocate more federal spending, but rather money-financed tax cuts.

I think the US could profitably gut “national security” outlays, and eliminate HUD, USDA, Commerce, Labor and Education. When I say money-financed fiscal programs, I mean money-financed tax cuts. Preferably payroll-tax holidays, financed by the Fed buying Treasuries and placing them into the Social Security Trust Fund.

Or, with conventional monetary policy, you can cut interest rates to zero (already there in Japan and Germany) and try QE, and pray banks lend out more, and maybe get asset values up. And trying chanting in front of the QE totem in Hall of Macroeconomics. Talk up negative interest rates (and paper cash zooms, and disintermediation too?). Banks in Japan say they are going out of business. But you need banks to lend!

Really, can we just call out the heavy artillery instead? Send in the helicopters, hell, send in the B-52s.

9. March 2019 at 01:33

Matthew Waters–

Thanks for your comments.

“So a helicopter money backdoor of tax cuts should exist as a tool to meet NGDP targets.”

I think the above sentiment is right given your context of 100% reserve-backed financial institutions. I think it is right in the present context too.

Of course, 100% reserves means no money is lent out by that particular financial institution (as George Selgin points out).

In that case, new money creation would have to come from money-financed fiscal programs.

You would still have “shadow-banking” under your system.That is financial institutions that are unregulated, and lend out money, but it would only be equity (since they could not create money).

This is a fascinating question, and I am dubious that the present system, that precludes the federal government from creating money, is the best.

It does seem like the financial class and the upper-class got together and created the present-day financial system and monetary-policy apparatus. Interest-group politics explains a lot about every federal agency.

Then they hired Rube Goldberg, plied him with hemp and Jack Daniels, and set him loose at Jekyll Island.

9. March 2019 at 03:49

Why is this trend not reflected in the tips spread?

9. March 2019 at 07:30

Scott,

I’m curious. Do you think the risk in owning Treasuries and a basket of securities that pay a dividend in proportion to US NGDP would be equal under perfect monetary policy?

Now, what about under inflation targeting?

9. March 2019 at 07:31

That’s securities that pay a dividend on proportion to US NGDP growth.

9. March 2019 at 07:38

And I’m referring to the level of risk.

9. March 2019 at 08:49

dtoh, A supply and demand imbalance is a market disequilibrium. I did not assume any sort of disequilibrium in the labor markets.

I’m just using the ordinary S&D for labor model for wages, just as you’d use the ordinary supply and demand for money model for the price level. Or supply and demand for apples for apple prices. If I recall correctly, you argued the CPI was determined not by the supply and demand for money, but rather disequilibrium in product markets. But the CPI is the value of money.

Wlliam, The TIPS spread refers to the CPI, not wages.

Michael, I don’t have a strong view on that. I would have thought that TIPS would have been regarded as less risky than conventional bonds, but that doesn’t seem to be the case.

9. March 2019 at 09:47

My favorite indicator (total private sector weekly wages: i.e. number_of_hours x hourly_wage x number_of_employees https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=mGyC) grew by an annualized 3.05%, which is a bit lower than its 4.5% post-2010 average, but well within normal fluctuations.

Number of employees growth is weak, and weekly hours are down.

Hourly wages increased at an 4.9% annual rate.

9. March 2019 at 09:56

Scott,

Thanks for your input. I think the risk should be the same, or at least close, but wonder if I’m missing something.

The point, of course, is that there’re potentially interesting implications if the answer to the question is yes. It may then mean that Treasury yields should, on average, be equal to NGDP growth expectations. This would make estimating the stance of monetary policy easier.

It seems too simple of an observation to have been missed by economists for so long though, so it seems likely I’m missing something perhaps basic.

It doesn’t bother me that the 50 states all have different NGDP growth rates, but perhaps it should. I think the relevant level of analysis is at that of currency issuer.

9. March 2019 at 09:57

I think that if March ends up being similar (say 3.5% annualized total private sector weekly wages growth), this could help justify a slightly looser monetary policy.

The Fed seems to be managing the “post-tax-cut sugar rush crash” relatively well, given that it doesn’t have market-based forecast of future nominal demand.

9. March 2019 at 10:18

Benjamin,

Yeah, the shadow banking issue is a big one. The financial crisis had three big sources of funds to the shadow banking sector:

1. Non-financial investors in Money Market Funds

2. Prime brokerage for hedge funds

3. Custodian banks reinvestment of cash collateral for securities lending.

It was rare for a real human being to invest their own assets in the shadow banking system. Most of the shadow banking deposits came from fiduciaries. Pension funds and 401k investors had ultimate interest in shadow banking deposits. The funds lent out securities and received cash collateral. The collateral was invested in “safe” assets, such as the top tranches of MBS and in commercial paper of investment banks.

https://www.forbes.com/forbes/2009/0622/mutual-funds-pension-securities-lending-meltdown.html

Securities lending should either have cash collateral in the 100% reserve accounts or should make far bigger disclosures. The collateral pool should be disclosed like a plan asset.

Another fiduciary are CFOs and Treasurers of publicly traded companies. CFOs tend to rely on commercial paper and bank credit lines to meet payroll and pay suppliers. In 1970, Penn Central defaulted on Commercial Paper. The CP market became scared of any company’s CP. Arthur Burns got banks to lend to companies in lieu of CP, with a promise of the discount window backing. CP after 1970 was issued with a backup bank line of credit.

Since I do not want the discount window to exist, I do worry about working capital in the case of no discount window or fractional-reserve deposits. Ideally companies would just raise more working capital from their long-term debt and equity. The SEC can have disclosure for possible severe liquidity risk.

In general, the 100% reserve system with no bailouts puts more onus on regulators. The Department of Labor and SEC would have the biggest roles in ensuring disclosure and preventing shadow banking. The state insurance commissioners also have responsibility for AIG and its security lending. The important thing is to move our focus on regulation up to the actual fiduciary.

9. March 2019 at 18:44

Egads, this is from Larry Summers, who is perhaps the macroeconomists’ economist. From his March 4 paper:

“This paper demonstrates that neutral real interest rates would have declined by far more than what has been observed in the industrial world and would in all likelihood be significantly negative but for offsetting fiscal policies over the last generation. We start by arguing that neutral real interest rates are best estimated for the block of all industrial economies given capital mobility between them and relatively limited fluctuations in their collective current account.”

So…if the West runs balanced national budgets, do we see 10-year government bonds at negative 3%?

The laugher: If real interest rates are negative, shouldn’t governments borrow money? After all, taxpayers would be getting paid to borrow money!

Gadzooks, I love macroeconomics. No one is ever wrong!

9. March 2019 at 22:54

AHE is a lagging indicator, just look at 2007-09 charts again. AWE (thus including more sensitive AWH) are more real time and nothing to see there. In fact, AWH fell, so AWE flatlined – for the All Employees data. The non-supervisory AWE looked actually bad. Don’t reason from the wrong data set!

9. March 2019 at 22:59

Matthew:

I do not understand 100% reserve banking. If a bank has 100% reserves, it means it does not lend out money. It is not a bank. It takes deposits and safeguards deposits, a perfectly worthy function, but not banking. (See George Selgin).

In a 100% reserve system, the only lending is by “shadow banks.” They take equity and lend it out.

In a 100% reserve system, it would be a near-necessity for the federal government to engage in money-financed fiscal programs, or possibly there would have to be chronic deflation.

I think there are some out there who have advocated for chronic deflation, such as Charles Plosser, former Fedster. Plosser strikes me as the type of central banker who would regard 2% annual deflation as nirvana itself, regardless of real economic output. In such a state of euphoria, who could care about trivialities such as RGDP?

9. March 2019 at 23:06

Matthew, Benjamin –

I agree with the idea of 100% Reserve Backing, as spelled out by the Chicago Plan. Assuming monetary offset, the Fed can hit any NGDP target with any reserve ratio. The higher the reserve ratio, the higher the monetary base – for a given NGDP. Therefore, it is in the taxpayers’ interest to have the highest reserve ratio possible, which is 100%.

Currently, M2 is $14.5 Trillion and the debt held by the public is $16.2 Trillion, so in order to keep NGDP the same as it otherwise would be the Fed would have to buy up most of the Treasury bonds in existence.

I also liked this statement – “Personally, I have an extremely strong belief in absolutely no government backing of private financial institutions.”

I would agree. I would add that the government should never back a private loan. It should either not assume the risk at all, or make the loan directly and keep the profits. If we switched from backing loans for education, mortgages and infrastructure to having the Treasury (or Fed) make those loans directly to individuals or the States then there would be several trillion more for the Fed to buy before resorting to helicopter money.

With this approach the Treasury would be a net interest earner instead of a net interest payer.

10. March 2019 at 02:07

A lot of capital formation happens outside of banks, or in particular banking deposits. Depository institutions own about $10 trillion of $22 trillion in regular loans.

Depository institutions also do not own most Treasuries. Households have $1 trillion in Treasuries, Pension funds have $2.4 trillion and foreigners have $6.3 trillion. With most of the debt monetized, these funding sources can invest in the $10 trillion of loans currently held by banks.

I want a rigid NGDP target with helicopter money if necessary. At worse under 100% reserve banking, NGDP is consistent but GDP shares move some from I to C. Considering the wastefulness of many bank investments, a higher Consumption share may not be a bade thing.

10. March 2019 at 02:29

“Speaking of full employment, the quality of workers in service industries is deteriorating rapidly. Service sucks.”

The robots are coming!

10. March 2019 at 11:06

James, I agree that AHE is a lagging indicator, but so is the CPI.

10. March 2019 at 17:52

Scott,

When I’m talking about a supply and demand imbalance (or expected imbalance,) I’m talking about a situation where marginal supply and marginal demand have been in equilibrium at a given price, but a change (or expected change) in either supply or demand occurs which causes marginal supply and demand to become imbalanced at the existing price.

Are you talking about something else?

10. March 2019 at 23:12

And AHE for All Employees is a new dataset. Try running it before 2007. AHE for Nonsupervisory and Production Employees is much duller, and times AWH to get Average Weeky Earnings actually bad. AWH gets cut quickly in a downturn/recession, much quicker than AHE.

The anecdotal “service is bad these days” meme could easily be mere structural/demographic change. So, young people are useless (structural/cultural) or there are not enough of them relative to wealthy baby-boomers (demographic), or both.

11. March 2019 at 06:26

@Benjamin Cole, you wrote “Yet, Trump has been right on monetary policy, and the Fed wrong. There is something that goes awry when “experts” get in charge of government policy. When even Trump is better than the experts…maybe we need to re-consider how things are done.”

In my opinion, the Fed was correct in not immediately accommodating the weaker growth outlook that I claim resulted from Trump’s policies, especially the Chinese trade war. This gave the stock market, our best proxy for an NGDP futures market, a chance to judge the impact of Trump’s policies. Once its negative judgement became clear, the Fed took on its more accommodative stance, and the Trump administration, somewhat cowed, began to become publicly more conciliatory on China. If the Fed immediately accommodates every policy decision with its guess of what the impact will be, then the Fed’s decisions become a political statement (i.e., the Fed loosening monetary policy = politicians made a bad decision); instead, the Fed needs to be responsive to the market in order to claim neutrality. Maybe with a true NGDP futures market the Fed would not need to delay, but with the stock market as a proxy, the Fed does need to delay.

11. March 2019 at 11:37

Ben, You said:

Yet, Trump has been right on monetary policy, and the Fed wrong.”

Actually he’s been wrong. A few years ago he criticized low rates, when in retrospect they were needed. In 2017, he opposed rate increases, the Fed did them anyway In 2018, the Fed almost perfectly hit their targets. So he’s been wrong, again and again.

dtoh, You said:

“Are you talking about something else?”

Yup.

Let’s review the original discussion, which was on what causes inflation. Obviously it’s a tautology that inflation is associated with shifts in supply and demand curves, because inflation by definition is a change in price.

My claim is that it makes more sense to look for the underlying causes of inflation in the supply and demand for money, not the supply and demand for 1000s of goods and services. My point is that even if there were no “imbalances” in the standard sense of disequilibrium, monetary stimulus would still lead to higher prices.

So yes, I misunderstood what you meant by imbalances.

James, Not sure that demographics changed all that fast between 2015 and today.

I don’t disagree that average weekly earning may be a better cyclical indicator than average hourly, but hourly probably correlates with core inflation. I still have an open mind on the inflation question—neither 2% or below 2% inflation would surprise me in 2020 and 2021.

11. March 2019 at 12:48

Back in 2008/09 AWH and AWE fell well before AHE.

I don’t really care about inflation, just excessive or too low NGDP growth. I know the Fed does worry about inflation as it is part of their mandate. However, the mandate is really healthy nominal growth, as we know, implied by the inflation/full employment combined mandate. They can and do choose to over-worry about inflation, and that is their own fault.

11. March 2019 at 16:16

Scott,

“My claim is that it makes more sense to look for the underlying causes of inflation in the supply and demand for money, not the supply and demand for 1000s of goods and services.”

I’m having a bit of hard time fully grasping this.

For example, what would happen if the economy was at full employment and the Fed announced they were going to cut interest rates in the future but made no change to the money supply?

Would that cause an increase in demand and an increase in the rate of inflation?

12. March 2019 at 16:28

dtoh, It depends on whether they planned to cut rates with an easy money policy or a tight money policy. If it were with an easy money policy (as most people assume in that example) then inflation would rise.