Natural interest rate bleg

I suppose I should know what the natural rate of interest is, given that I’m a monetary economist. But I see the term used in two radically different ways, and am not sure which version is correct:

1. The real interest rate that would exist if the economy were at full employment and stable prices (or on-target inflation).

2. The real interest rate that would be expected to push the economy back to full employment and stable prices (or on-target inflation).

A recent NY Fed piece used the first definition:

The Laubach-Williams (“LW”) and Holston-Laubach-Williams (“HLW”) models provide estimates of the natural rate of interest, or r-star, and related variables. Their approach defines r-star as the real short-term interest rate expected to prevail when an economy is at full strength and inflation is stable.

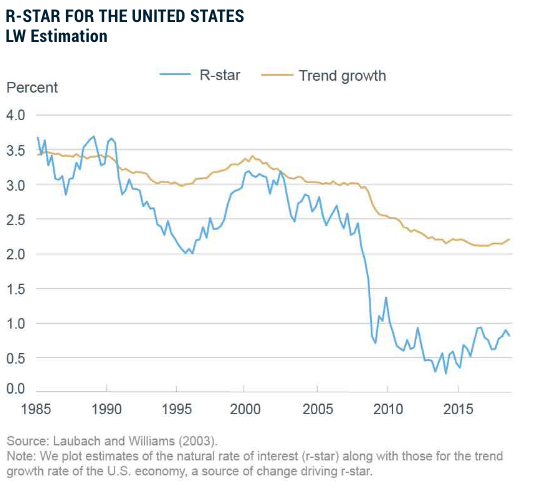

The accompanying graph shows their estimate of the natural real rate for the US:

Obviously, it would have been a disaster if the Fed had set the real rate at that level during the Great Recession. Rather the authors are showing the real rate that would be appropriate in the counterfactual case where the economy was at full employment.

Obviously, it would have been a disaster if the Fed had set the real rate at that level during the Great Recession. Rather the authors are showing the real rate that would be appropriate in the counterfactual case where the economy was at full employment.

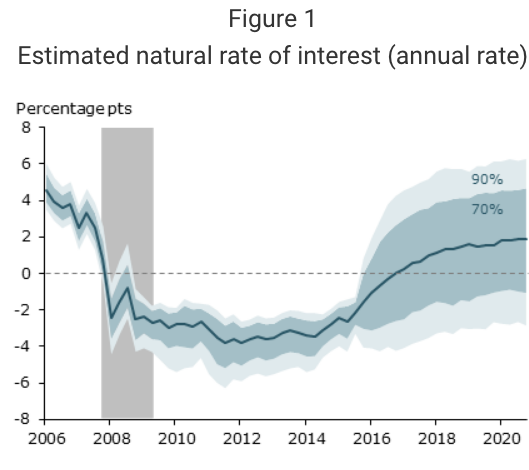

In contrast, an article by Vasco Cúrdia at the San Francisco Fed uses a very different concept when describing the natural rate:

The natural rate of interest is the real, or inflation-adjusted, interest rate that is consistent with an economy at full employment and with stable inflation. If the real interest rate is above (below) the natural rate then monetary conditions are tight (loose) and are likely to lead to underutilization (over-utilization) of resources and inflation below (above) its target.

At first glance, that sounds similar to the New York Fed’s definition, but he later clarifies that this is the rate expected to lead to full employment, and that the natural rate will fall when the economy is depressed:

During the economic recovery, the natural rate was kept low by weak demand due to a larger propensity to save in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

As a result, Cúrdia’s estimate of the natural rate is dramatically lower than the NY Fed estimate:

I like Cúrdia’s definition better, and it’s the one I’ve always used. During the Great Recession, the Fed would have had to initially cut real rates to very low levels to push the economy back to full employment. But if a magic wand (say a quick adjustment of wages and prices by God) had suddenly gotten us back to full employment, then the equilibrium interest rate would be much higher, as is normally the case during booms. That’s the NY Fed estimate.

Alternatively, if monetary policy had been expansionary enough to prevent a Great Recession, the natural rate would not have fallen as sharply.

Here’s the problem. I see each version of the natural rate being used by various economists, and I don’t know which use is conventional. This makes it hard to communicate with other macroeconomists.

Personally, I don’t like speaking Spanish or Keynesianism. But when speaking with Mexicans I at least try to use a bit of Spanish, and when speaking with Keynesians I at least try to use a bit of Keynesianism. But if I don’t know the proper meaning of the terms, then it’s hard to communicate.

Can someone please help me?

Cúrdia explains the difference this way:

Williams (2015) estimates the natural rate to be low by historical standards, but not nearly as low as those shown in Figure 1. The main difference is that Williams uses the statistical model of Laubach and Williams (2003), which is better suited to determine the longer-run level of the natural rate. By contrast, my analysis is suited to find short-term fluctuations in the natural rate.

But that doesn’t seem adequate to me; it seems like they are describing entirely different concepts. And even if it’s correct, it suggests that economists should never refer to the term ‘natural rate of interest’ without first specifying whether it is the short or long run version. Indeed Cúrdia hints at this inadequacy when describing how one could draw incorrect policy implications from the alternative definition:

This distinction is important in evaluating monetary conditions. In contrast to my results, the interest rate gap using the Laubach-Williams measure of the natural rate has been negative since the recession. According to their estimate, the Fed response to the crisis was expansionary because it lowered the real interest rate below its longer-run natural level.

Obviously, if the natural rate is defined as the rate that would prevail if the economy actually were at full employment, it’s of zero value in determining whether monetary policy is expansionary in an economy that is far from full employment. So this isn’t just “semantics”, there are important policy issues at stake here.

Nor can the natural rate of interest be described as the appropriate real interest rate on long-term bonds, as that rate will itself depend on the future path of monetary policy.

Update: Commenter Judge Glock left the following comment, which seems correct to me:

Maybe this isn’t helpful, but I think it just has to do with referring to different parts of the Taylor Rule. For the “long-term” natural rate, people mean the r* as in r* + a1(infl – desired inflation) + a2(output gap – desired output)= i, or, in other words, the intercept of the Taylor Rule, or its equivalent. Other people seem to refer to the natural rate as the final i, the dependent variable of the Taylor Rule, or the output of the equation, which represents the short-term rate when factoring in output and inflation gaps. It may be mere preference or semantics, but it seems to me the i more closely approximates the original Wicksellian understanding of the “natural rate,” or the rate that will keep the economy at equilibrium, while the r* more closely approximates the combination of growth rate and time preference. The confusion, though, could be emerging from the original Laubach-William paper, which, if I’m reading it correctly, estimates the “natural rate” or “r*” by looking at output gaps and real interest rates over time, thus treating the r* as something like the Taylor Rule’s i, even while they also refer to r* as the combination of the economic growth rate and household time preference not dependent on output gaps.

Update#2: Rayward directed me to an excellent 2015 Tyler Cowen post on the topic.

Tags:

11. December 2018 at 11:46

Why is the natural rate defined as a short-term rate? Is it because, historically, this was the only rate at the Fed’s disposal? Seems awfully simplistic.

Today, the Fed has a $4.1 trillion balance sheet and can act over the whole yield curve. They wanted to flatten the yield curve in 2011 with Operation Twist and succeeded.

Short-term real rates are too high rate now, and long-term real rates are too low. The Fed should fix this via selling assets and holding off on FFR hikes for a bit.

11. December 2018 at 11:57

The problem with defining the natural interest rate as the rate that will get you back to full employment is that you haven’t said how quickly you’re supposed to get there. Maybe a real rate of negative 10 percent would have ended the recession in only a few weeks, while a real rate of minus 2 percent would also have worked, but taken much longer.

Without specifying a time period over which the adjustment is to happen, the rate as you define it is indeterminate.

11. December 2018 at 12:46

Scott, fwiw I don’t think the distinction between the two is what you’ve put your finger on. I think the distinction is more about short- versus longer-run timeframes (i.e. what Cúrdia offers as the distinction). For one thing, why would the first graph fall so sharply around 2009, if it were supposed to be showing the real rate under normal conditions?

In any event, check your block quotation; I think you put your own words (“At first glance, that sounds similar…”) as part of the block quote?

Also, it just so happens that this morning I was (for another project) reading Joseph Schumpeter’s analysis of business cycle theories, and he gets into the different meanings attached to “equilibrium” or “natural” interest rate among Wicksell, Hayek, Keynes, etc. You might want to read just a few pages of it, to see historically where it comes from. (Most of the modern discussions cite Wicksell of course as the source of the concept.)

So if you go to this link, the discussion starts on page 1083, section 8.

11. December 2018 at 13:25

Maybe this isn’t helpful, but I think it just has to do with referring to different parts of the Taylor Rule. For the “long-term” natural rate, people mean the r* as in r* + a1(infl – desired inflation) + a2(output gap – desired output)= i, or, in other words, the intercept of the Taylor Rule, or its equivalent. Other people seem to refer to the natural rate as the final i, the dependent variable of the Taylor Rule, or the output of the equation, which represents the short-term rate when factoring in output and inflation gaps. It may be mere preference or semantics, but it seems to me the i more closely approximates the original Wicksellian understanding of the “natural rate,” or the rate that will keep the economy at equilibrium, while the r* more closely approximates the combination of growth rate and time preference. The confusion, though, could be emerging from the original Laubach-William paper, which, if I’m reading it correctly, estimates the “natural rate” or “r*” by looking at output gaps and real interest rates over time, thus treating the r* as something like the Taylor Rule’s i, even while they also refer to r* as the combination of the economic growth rate and household time preference not dependent on output gaps.

11. December 2018 at 14:42

So the FED is using indicators that aren’t even defined???

Another good reason for NGDP targeting.

11. December 2018 at 14:45

I have always thought of the real interest rate as a spread over the current inflation rate such that the Fed would neither be “easy” or “tight”

If we look at the Taylor rule, it is the rate we should at be if inflation was on target and GDP equaled potential GDP.

It is, of course, bulshytt. It cannot be measured, it can only be guessed at.

11. December 2018 at 15:00

Brian, I think the distinction is more between the short run and the long run, as opposed to the short term rate and the long term rate. In the short run, even long term rates fell to a low level. But again, I don’t think it’s possible to define a natural long term rate, as it depends on the future course of monetary policy.

Jeff, Good point. I think of the time frame in terms of the central bank’s vision of the optimal period to try to get back to full employment. But this is another reason why it’s a questionable concept.

Bob, Thanks for pointing out the block quote problem. Those who argue for the “long run” version, are implicitly claiming that in the long run the economy returns to equilibrium at full employment. So it’s both the long run and the full employment natural rate. Note that this is how the NYFed describes it.

Regarding the sharp fall in 2008-09, that’s because the housing slump was expected to last a long time, and that expectation turned out to be correct. So even the long run natural rate fell.

But my basic point stands, the NYFed and the SF Fed can’t both be right. Which one is wrong?

Judge, Very good comment. That seems right to me. Maybe I’ll add an update.

11. December 2018 at 16:06

Neutral, Natural, Potential. All very confusing concepts. Cannot fathom how they can serve as “guides to policy”. Seems like having a drunken guide in unknown and difficult terrain. You´ll likely end up falling from a cliff.

Appears to be a favorite “playground” for academics…

11. December 2018 at 16:30

Re definition 2, if say a negative 1% rate would push the economy back to full employment, mightn’t a negative 2% rate push it back too? Just a little more quickly? As would a negative 3% rate?

11. December 2018 at 16:59

Marcus, Not just academics, policymakers too!

Bill. Yes, but think of it this way. Let X months be the central bank’s estimate of the optimal monetary impact lag to get back to full employment. Then the natural rate is the current interest rate setting that gets you there in X months.

11. December 2018 at 17:28

That makes sense.

With hindsight, our Fed got us there in about X=110. They need to recalibrate more quickly.

12. December 2018 at 09:35

Here is Cowen’s summary from 2015 (which references Sumner among other usual suspects): https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/11/whats-the-natural-rate-of-interest.html

12. December 2018 at 09:45

Rayward, Thanks, I added an update.

12. December 2018 at 17:34

Instead of interest rates, I would put *direct* effects of monetary policy in three buckets:

NGDP = f(IOR, OMOs, discount window).

Let’s say IOR can be negative with sufficient restrictions on cash printing.

Sep. 2008 had a 1931-32-like reduction in the monetary base. Money Market Funds and collateral posted with brokers served as money. A significant negative IOR would eventually reduce the demand for money. Enough OMOs could have a similar effect.

In reality, 2008 had a greatly expanded discount window before QE1. The Fed printed a lot of new money. In Sep. 2008, half the new money was sterizized with increased reverse repos. For 10/9/08-12/15/08, most reserves were sterilized with 0.75% to 1% IOR.

Since multiple policy instruments exist with different effects on interest rates, the idea of a “natural interest rate” seems underdefined.

Sorry if this post was too long.

12. December 2018 at 21:53

If Woodford’s Interest and Prices is the New Keynesian bible, then I would interpret this p.248 snippet as fitting definition 1:

“the equilibrium real rate of return in the case of fully flexible prices … the real rate of interest required to keep aggregate demand at all times equal to the natural rate of output.”

https://books.google.com.au/books?redir_esc=y&id=8AlrisNOOpYC&q=natural+rate+of+interest

(To me your definition 2, particularly your 16:59 comment, sounds more like an optimal interest rate rule, that would have the natural rate as one of its arguments.)

12. December 2018 at 22:29

Declan, You said:

“the equilibrium real rate of return in the case of fully flexible prices … the real rate of interest required to keep aggregate demand at all times equal to the natural rate of output.”

Those are two very different concepts. In late 2008, the interest rate consistent with a flexible price economy was probably positive. The interest rate required to keep AD equal to the natural rate of output was negative.

I also don’t like the way Woodford defines AD as a real concept (output). It’s a nominal concept. Otherwise a decrease in AS would also be a decrease in AD.

13. December 2018 at 03:48

Complementing my previous comment:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2015/10/25/looking-for-wally-when-there-are-many-wallies/

17. December 2018 at 06:26

Question. What would happen if there was no FED to be “too tight” or “too loose”. 1907 was the last real-time experiment of what would happen in a deep recession without a FED. I sometimes think the man, JP Morgan, was so freaked out by his work during 1907 that he thought he could wish away future panics if some “higher power” could be there at all times to play his role. But compare what our FED did when it first faced its own 1907, circa 1930. I believe it was considered a disaster that was accelerated by the FED. So seriously, what would happen if we did away with the amendment that created the FED? Look what they did. They made up this idea of QE. When one reflects, isn’t this a bit scary? At least they don’t listen to politicians (except Burns).