Multiplier mischief

Multipliers are ratios. That’s really all they are. There is the money multiplier (M2/MB), the fiscal multiplier (1/MPS) and the velocity of circulation (NGDP/MB, or NGDP/M2). If you assume these ratios are stable, you can derive some very interesting policy results. Of course the ratios are not completely stable, but may be stable enough to be of some value. Sometimes. My own view is that multipliers aren’t particularly useful, but today I’d like to assume the opposite, and show that the implications are not necessarily what you might assume. (And please, no comments from MMT zombies “explaining” to me that multipliers don’t exist.)

Milton Friedman faced a quandary when trying to explain how bad government policies led to the Great Depression. If he defined the money supply as “the monetary base” (as I prefer), people would have pointed out that the base increased sharply during the Great Depression. Alternatively, he could have adopted the market monetarist practice of defining the stance of monetary policy in terms of changes in NGDP. Thus falling NGDP during 1929-33 was, ipso facto, tight money. His critics would have objected that this begged the question of how could the Fed have prevented NGDP from falling.

So he split the difference, and settled on M2 as both the definition of money, and the indicator of the stance of monetary policy. He suggested that, “What is money?” was essentially an empirical question, not to be determined on theoretical first principles. His statistical analysis led him to conclude that M2 (which unlike the base did fall during the early 1930s) was the preferred definition of money. And also that growth in M2 should be kept stable at roughly 4%/year.

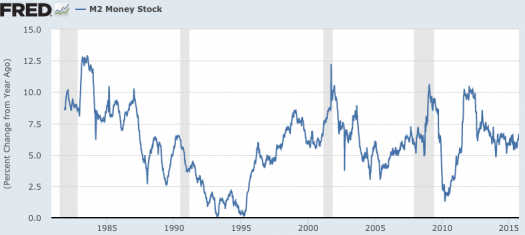

In my view M2 no longer represents a good definition of money, using Friedman’s pragmatic criterion. Look at M2 growth in recent years:

I don’t know about you, but I see almost no correlation with the business cycle. Indeed M2 growth soared in the first half of 2009, making money look “easy”, which is obviously crazy. So if Friedman were alive today, how would he define money? The base still doesn’t work, as reserves also soared in 2008-09. Nor does M2. I don’t have a good answer, but I suspect that coins might be the best definition. Unlike the base and M1, periods of illiquidity probably don’t lead to massive hoarding of coins. They are primarily useful for making transactions (although a sizable stock is held in piggy banks.)

I don’t know about you, but I see almost no correlation with the business cycle. Indeed M2 growth soared in the first half of 2009, making money look “easy”, which is obviously crazy. So if Friedman were alive today, how would he define money? The base still doesn’t work, as reserves also soared in 2008-09. Nor does M2. I don’t have a good answer, but I suspect that coins might be the best definition. Unlike the base and M1, periods of illiquidity probably don’t lead to massive hoarding of coins. They are primarily useful for making transactions (although a sizable stock is held in piggy banks.)

Unfortunately, I could not find any data for the stock of coins in circulation. (Which is a disgrace, when you think about the 100,000s of data series the St Louis Fred does carry. As I recall, back in the 1990s coins were almost as important a part of the base as bank reserves.) But I did find data on annual coin output. For simplicity, I chose unit output, but value of output (which counts quarters 5 times more than nickels) would almost certainly lead to broadly similar results. In the list below I will show the change in annual coin output, compared to the year before, and also the change in the unemployment rate at mid-year (June) compared to the year before. The unemployment rate change is in absolute terms:

Year * Coin Output * delta Un

2000: +28.1% -0.3%

2001: -30.9% +0.5%

2002: -25.7% +1.3%

2003: -16.5% +0.5%

2004: +9.5% -0.7%

2005: +16.1% -0.6%

2006: +1.4% -0.3%

2007: -6.9% 0.0%

2008: -29.8% +1.0%

2009: -65.0% +3.9%

2010: +79.6% -0.1%

2011: +28.7% -0.3%

2012: +13.9% -0.9%

Unfortunately my data ends at 2012, but that’s a really interesting pattern. Especially given that I don’t have the data I’d actually prefer. I’d like the change in the size of the coin stock; instead I have the change in the flow of new coins (but not data on old coins withdrawn.) It’s more like a second derivative.

In any case, it’s an amazing correlation. The signs are opposite in every case except the one where unemployment doesn’t change at all. Coin output falls during years when unemployment is rising, even years like 2003 when unemployment is rising during a non-recession year. And even better, the biggest change by far in coin output (proportionally) is in 2009, which also saw the biggest change by far in unemployment.

If you are not good at math then you’ll have to take my word for 2010 being a smaller change in proportional terms. Indeed if you look at actual coin output in levels, 2010 was the second smallest in the sample, 2011 the third smallest, and 2012 the 4th smallest. The decline in 2009 was so great that we never really climbed out of the hole.

Now let me emphasize that there’s an element of luck here. If we had coin data for 2013 and 2014 I doubt the relationship would hold up. Coin output seems to be in a steep secular decline. So it’s partly coincidence that the signs are reversed in virtually every case. But not entirely coincidence. Perhaps someone could do a regression (using first differences of logs of coin output—so that the 2009 change will be larger than 2010) and confirm my suspicion that this relationship does show something real. Falling coin output is associated with recessions.

But does it cause recessions? If only you knew how tricky the term ’cause’ really is! Krugman basically called Friedman a liar (soon after Friedman died) for claiming that tight money caused the Great Depression, whereas in Krugman’s view Friedman’s data pointed to the real problem being a non-activist Fed—they didn’t do enough to prevent M2 from falling. But they didn’t cause it to fall with concrete steppes. The base didn’t fall.

I’ve always believed we should think of “causation” in terms of policy counterfactuals. Suppose the Fed had acted in such a way that M2 didn’t fall. And suppose that in that case there would have been no Great Depression. Then if the Fed was capable of preventing M2 from falling (which is itself a highly debatable claim) then there is a sense in which Friedman was right, the Fed did cause the Great Depression. Again, that’s if they could have prevented M2 from falling, and if stable M2 would have prevented a depression–both debatable (but plausible) claims.

My claim is that if we use Friedman’s pragmatic criterion for defining money, then coins might possibly be the best definition of money for the 21st century. If the Fed had acted in such a way that coin output was stable in 2007-09, or at worst declined along its long run downward trend, then there would have been no Great Recession. So in that sense the fall in coin output “caused” the Great Recession. But I could also find a 1000 other “causes,” such as plunging auto sales.

Can the Fed control the coin stock? I’d say they could in exactly the same way they can control M2 (or nominal auto sales), via a multiplier. The baseline assumption is that both the coin stock and M2 move in proportion to the base. That would be the case if the M2 and coin multipliers were stable. If the multipliers change, then the Fed simply adjusts the base to offset the effect of any change in the coin multiplier.

No let me quickly emphasize that I view the preceding as an extremely unhelpful way of thinking about monetary policy and the Great Recession. I still prefer to define money as the base, as the base is directly controlled by the Fed. And I prefer to define the stance of monetary policy as NGDP growth expectations. And I prefer to think of tight money as setting the monetary base at a level where NGDP growth expectations fall below target, as in 2008-09. I’d just as soon leave coins to children with piggy banks and nerdy collectors. But if you insist on defining money using Friedman’s pragmatic criterion, then coins are my definition of the money stock.

A penny for your thoughts?

PS. I have a new post on the Phillips Curve at Econlog.

Tags:

5. October 2015 at 13:46

for several years I was tracking M3, and then the Fed decided to stop reporting M3.

M3 does track the NGDP than the other monetary aggregates, but the correlation still isn’t that strong.

M3 did not move higher when QE was exploding, continuing to move sideways into 2011 and has been growing at ~4% 2012 to 2015, not too far off from NDGP.

5. October 2015 at 13:51

I ran the regression using 1950-2014 data from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Mint_coin_production (it goes way back, but FRED unemployment starts in 1950).

I get a coefficient -1 +/- 0.6, t-stat 1.7 (just barely significant at the 10% level). R^2 is about 4%. That’s for the *value* not the number of *units*. Interestingly, using units rather than value substantially strengthens the result: now the coefficient is -2.5 +/- 1, t-stat 2.7, p<1%, R^2 10%. Odd.

5. October 2015 at 13:53

Note to people who interested in reproducingmy result: http://www.convertcsv.com/html-table-to-csv.htm is a handy tool for extracting the data from the Wikipedia page.

5. October 2015 at 13:57

When you pragmatically define money, you need to take care that you aren’t inadvertently defining it as “whatever makes monetarism seem correct”.

5. October 2015 at 14:11

Doug, That sounds right.

Sam, Thanks, that’s very interesting. What’s the correlation for my data sample?

Max, Yup, and that’s my problem with old monetarism.

5. October 2015 at 14:30

“If you assume these ratios are stable, you can derive some very interesting policy results. ”

Not true. You have to also assume that you got the causality right. Eg. In the real world loans create deposits and then banks convert Å›ome ofeir bondholdings into reseves’ so even if M2/MB was stable it still wouln’t follow that the CB can impact M2 by fiddling with MB.

5. October 2015 at 14:36

@Scott, -84%

5. October 2015 at 15:05

Sam, The R2 is negative 84%? Seriously?

OhMy, If the ratio is stable and you change the denominator then the numerator will change.

And in the real world “it’s a simultaneous system” and hence comments like “loans create deposits” are meaningless.

5. October 2015 at 15:11

No that’s correlation. R^2 is, well, 84% squared, or about 70%. But there’s not much you can say from 10 years of annual data. The Mint has monthly coin production for the past few years (maybe if you ask they can go back further); it would be interesting to study the correlations at say quarterly frequency.

5. October 2015 at 15:23

Sam, Thanks. Not to keep forcing you to do work, but I’d guess the prob value is pretty high, despite only 13 years. Am I right? (or the t-stat, if that’s what it gives you)

In any case, I did say coins were my definition of M for the 21st century (using Friedman’s criterion), I suppose it doesn’t work as well in the past.

On the other hand depression years like 1921 and 1931 tend to be very valuable coins for collectors, so I imagine there was some relationship going back to the early 20th century as well. And of course as I pointed out my “model” was far from optimal, mixing first and second derivatives. I’m not sure what the optimal model would look like.

5. October 2015 at 16:16

Maybe it’s the increased unemployment that caused the coin supply to fall.

5. October 2015 at 16:23

@Scott, Well t = r / sqrt( (1-r^2) / (N-2) ) is roughly 5, but presumably some adjustment for serially correlated residuals is required to get correct standard errors. Both the coin issuance and the unemployment rate vary approximately at the timescale of the business cycle, so if we estimate that 13 years of data gives something like 4 truly independent datapoints, then we get a more realistic estimate of 2 for the t-stat. So it’s modestly convincing, statistically. But note that applying a similar adjustment to the full 65-year timeseries makes the ~32% correlation statistically insignificant.

5. October 2015 at 16:32

BTW, M1 has a much better correlation with the business cycle than M2.

5. October 2015 at 16:43

Also, in terms of how the relation changes over time, the model performs poorly from 1965-1985, and the statistics are dominated by the effect of the Great Recession, primarily the ’08-’09 years. It would be reasonable to wonder if there was an exogenous shock to the coin stock that coincided with the financial crisis.

5. October 2015 at 16:48

Scott, dare I ask the forbidden question? Is the book still looking like its coming out this year?

5. October 2015 at 16:52

http://www.usmint.gov/about_the_mint/?action=coin_production

Mintage of circulating coins (ex pennies)

2011 8200M (3262M)

2012 9336M (3321M)

2013 11907M (4837M)

2014 13281M (5135M)

2015 11859M (5446M) **ytd

5. October 2015 at 17:01

Quarter output was distorted lower during 2009-11 due to the end of the state quarter series and beginning of the park quarter series; a lot of collections were dumped back into circulation.

However, the evidence is that the recession was more important, as many people emptied their piggy banks for economic reasons.

5. October 2015 at 17:11

Penny for my thoughts? Sure.

Shorter Sumner: Friedman data mined the Great Depression, found something that seemed to ‘explain’ the data in the same way as the price of butter in Bangladesh ‘explaining’ world GDP (also a statistical artifact), and Friedman was ultimately proven that his proposition is wrong as a universal truth, it just held for a certain time period. Now Sumner wants to inherit the mantle of Milt and comes up with an even more tortuous definition of tight/easy money, akin to Shakespeare’s ‘night is day and day is night’ semantics.

I found it amusing that Sam was schooling Sumner, and Sumner anxiously awaiting the reply. But Sumner thinks nothing of the Bernanke et al 2003 FAVAR paper that found almost no effect of Fed monetarism; apparently he’s not even read it though it comes from the famous Ben.

OT – Sumner however is ‘right’ (wrong) on ridding the world of beavers. If dinosaurs had taken his advice, we’d not be here… (internet scrape): Kimbetopsalis simmonsae, as the new species has been named, was a plant-eating creature that resembled a beaver. The remains of this large, rodent-like animal have already given scientists clues about how mammals were able to “take over” the planet after the dinosaurs died out.

5. October 2015 at 17:13

Coins data is available for Japan:

http://www.boj.or.jp/en/statistics/boj/other/mb/

It also has a secular decline, but YoY change doesn’t match up very well with Japan’s NGDP. There are major declines in coins in 1991-2,

1994, 1998, 2005 and 2008-9 while the recessions are in 1991-2, 1998, 2001 and 2008-9 (your dates may vary). Basically, 1991, 1998 and 2008 match, but coins predicts major recessions in 2005 and 1994.

I will post a graph …

5. October 2015 at 17:13

Well, if you want my two cents, life has been going downhill since they got rid of the Buffalo Nickels.

5. October 2015 at 17:13

Off topic:

Marcus Nunes taking Bernanke to task:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2015/10/05/bernankes-failure/

And Dean Baker endorsing monetary offset (at least in one direction):

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dean-baker/donald-trump-and-the-fede_b_8248378.html

5. October 2015 at 17:23

And here is a graph of the YoY growth rate of coins:

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2015/10/coins-as-monetary-aggregate.html

5. October 2015 at 17:45

SS,

Wrong again. The ratio is stable until you interfere, just ask Ben Bernanke.

And no, it id not a simultaneous system. Loans create deposits, deposits don’t create loans, ask anybody who worked at a bank.

5. October 2015 at 20:08

Fred2 does have wacl which is the weekly coin reserves in federal reserve banks.

One issue … Coins are assets not liabilities of the federal reserve.

5. October 2015 at 20:11

Scott, I really like your delving into the components of the monetary base. What’s intriguing is how the $100 bill has dominated growth in the base. Coins and small denominations have some economic relationships, but less than I’d liked. (You’d imagine that if the $100 bills actually circulate, they’d demand-pull smaller bills into existence as change.) Fed data suggests some 50% of currency circulates abroad, which probably accounts for much of the $100 demand.

This US coin data is not in FRED, but in FRASER.

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/?id=407#!6518

(It takes a lot of grunt work to get a good time series, but it’s all there.)

Coins are, in a sense, super-senior currency base – direct obligations of the treasury, rather than federal reserve notes that are partially backed by “treasury currency”. So yo are absolutely right in a legal sense. Coins are the only treasury currency out there.

5. October 2015 at 22:36

1. Look at the second graph on http://www.philipji.com/item/2015-09-06/a-fed-rate-hike-wont-have-adverse-results-for-now to see a monetary measure that exactly mirrors the 2008-09 recession.

My Kindle ebook “Macroeconomics Redefined” has a similar graph for the period 1961 to 2015.

2. The velocity of money runs exactly parallel to interest rates (I’ve taken Moody’s Aaa bonds as a benchmark) over five and a half decades

3. In my book I also show why the money multiplier can never be greater than one.

5. October 2015 at 22:37

I forgot to mention that the velocity of money graph running parallel to interest rates can be seen at http://www.philipji.com/item/2014-04-02/the-velocity-of-money-is-a-function-of-interest-rates

6. October 2015 at 03:35

@scott

Hate to say this but the economy has less to do with coin production than…

Poor coin inventory management by the FRB

Production disruptions at the Philadelphia Mint

Beginning and cessation 50 State Quarters Program

Demand for millennium (Year 2000) coins

Introduction of coinless slots at casinos

Cold summers when people put less coins into Coke machines

Hot summers when people put more coins into Coke machines

Also, I if you want data for coins in circulation, it’s basically equal to total historical cumulative production. These days coins taken out of circulation annually by the mint is minuscule ($10 to $20MM).

6. October 2015 at 05:18

Thanks Sam, Someone else said it holds for the past three years, so now we have 16 years in a row (with one tie). That’s pretty amazing. I’d add that it also holds well in the interwar years, with coin output plunging in depressions. So there really is something there, but I guess it doesn’t hold during the Great inflation.

E. Harding, M1 is better when? And was it better when Friedman did his study and concluded M2 was better? Of course this is all angels on a pin nonsense, none of these are very useful.

Thanks Steve. I’m surprised it’s still holding.

CA, December 1st, this year. Finally.

Jason, I have a very special model, which only applies to the US, and only in the 21st century.

Michael, Thanks for the links.

OhMy, Surely you didn’t think I assumed it would be stable after the Fed started targeting it? It wasn’t even stable before.

Jon, Those coins are not in circulation.

Thanks Jknarr. I have a very recent Econlog post that discusses $100 bills.

Philip, Thanks for the links.

dtoh, This was also true in 1921 and 1931-33 depressions, were those also affected by Coke Machines and state quarter collections?

6. October 2015 at 05:25

@Prof. Sumner

I the monetary base is distorted by the level of bank reserves held at the FED, why not take “currency in circulation” ?

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/WCURCIR/

6. October 2015 at 05:27

Scott,

To get good coin data, look through the “Treasury Currency Outstanding” section of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, which is almost entirely composed of coin.

From the Fed’s website: “Treasury currency outstanding: Coin and paper currency (excluding Federal Reserve notes) held by the public, financial institutions, Reserve Banks, and the Treasury are liabilities of the U.S. Treasury. This item consists primarily of coin, but includes about a small amount of U.S. notes–that is, liabilities of the U.S. Treasury–that have been outstanding since the late 1970s. U.S. notes are no longer issued.”

6. October 2015 at 13:16

The chief problem with using coinage as any sort of indicator of monetary policy is that people decide how many coins to hold, not the Fed or any other monetary authority.

For monetary policy to have an effect, the Fed first has to implement a change that affects the economy. The Fed has no control over the number or type of coins I hold, or anyone else holds. It can’t, for example, force me to hold more than I want.

And the same goes for currency in circulation (coins plus paper bills). As prices change, and the economy fluctuates, people make independent decisions as to how much currency to hold. The Fed merely provides them what they want regardless what its policy goals are at the time. If anything, currency growth lags inflation as people grudgingly react to rising prices by deciding to withdraw larger amounts each time they need cash.

Any meaningful relationship between coins or currency and the economy would be at best coincident, and probably lagging, since most people don’t recognize a recession until they lose their own job.

6. October 2015 at 14:30

Rod,

Yes, everybody gets it except Sumner, he apparently never will.

6. October 2015 at 16:13

Scott,

Take a look at the year-over-year change in the real monetary base, which has a relatively close alignment with the business cycle through the decades. It’s easy to calculate at the FRED database (St Louis Fed). Deflate the monetary base (AMBSL) with the headline CPI (CPIAUCSL) and then select the rolling 1yr % change. Note that because of the extreme changes in recent years it’s best to view the graph in either a pre- or post-2008 time frame. It’s hardly a silver bullet, but it’s a good first approximation for monitoring the trend in Fed monetary activity, if only on the margins.

–Jim

6. October 2015 at 16:30

OhMy: I’m not going to go there. I’m just raising issues with treating coinage as some sort of guide to what money is doing.

For one example, what’s the difference between a dollar bill and a dollar coin from a monetary policy perspective? They’re both money, and equivalent money at that, so why separate out one or the other? If we suddenly did away with dollar bills and five dollar bills and substituted coins instead, would that mean anything from a monetary policy perspective?

What I find most interesting about this currency/coinage discussion is that it’s backwards. Currency growth lags inflation, or at least it did in years past. And yet the monetary base, which in the 70’s was mostly currency in circulation, was considered a leading indicator of inflation and the economy.

Well, if 3/4 of a leading indicator of inflation is a coincident/lagging indicator of inflation, subtracting it out might prove useful. Turns out that it was, the result being Effective Reserves. And Effective Reserves reliably led both turns in the economy and inflation from the early 50’s until 1980 when NOW accounts were introduced.

6. October 2015 at 19:01

@Sumner

I am going to suggest you have a dialogue with Robert Wenzel(nom de plume) over at “economicpolicyjournal.com”, who I also referred your “out of ammo” post to, which he subsequently linked at his site.

Not only does he routinely calculate money supply, he does so on an expounded method first developed by Rothbard…and he’s done it on a professional scale that would shock you(but I can’t divulge).

Anyway, there’s a few other out there that do money supply calcs, obviously the Fed no longer reporting M3 has its impacts as well….but RW’s metrics are well thought out.

There is no one more interested in money supply calculations than Austrians…it might be a good place to look even if you don’t agree in concept, the data itself you might find useful.

7. October 2015 at 02:37

“Fed data suggests some 50% of currency circulates abroad, which probably accounts for much of the $100 demand.”

When I go down to Argentina, they pay better rates for 100’s than 20’s and won’t accept bills with even the smallest of tears… Demand down there, for USD, is insatiable.

7. October 2015 at 05:20

Jose, Yes, you can use currency held by the public, but it doesn’t really correlate that well anymore.

Thanks JP. The relationship holds for the 3 most recent years—which makes 16 in a row (with one zero change)

Rod, Isn’t the same true of M2? And see my new post at Econlog.

I’d add that in the data set I provided it doesn’t seem to be lagging. The growth went negative in 2001 and 2007. That’s as timely as almost anything else you could come up with.

James, It works sometimes, but not others.

Nick, Why should I be interested in the monetary aggregates? What do they tell me that the Hypermind NGDP futures market doesn’t tell me?

7. October 2015 at 12:13

“Why should I be interested in the monetary aggregates?”

I’m not familiar with the metrics surrounding “Hypermind NGDP” futures, but I think it would be helpful if you are seriously looking for some correlation between the economy and monetary base to try to get a larger picture…(beyond coins)

Had you not gone down the rabbit hole I wouldn’t have offered anything. Maybe you meant it in jest and it flew over my head.

🙂

Beyond that, it’s not the aggregates per se that’s interesting- it’s their change.

7. October 2015 at 12:22

James Picerno: You wrote: “Take a look at the year-over-year change in the real monetary base, which has a relatively close alignment with the business cycle through the decades….Note that because of the extreme changes in recent years it’s best to view the graph in either a pre- or post-2008 time frame. It’s hardly a silver bullet, but it’s a good first approximation for monitoring the trend in Fed monetary activity, if only on the margins.”

James, try this and see what you get for a result: Look at the Monetary Base minus Currency in Circulation for the period 1950 to 1980. (I call the result Effective Reserves.) Then compare the result with economic contractions, and particularly with the start of economic expansions over that time frame. I’m curious what you’ll find using numbers available today.

I did the same analysis over 35 years ago and found that Effective Reserves (which the Fed has direct control over, or used to have before the QE experiment) led economic swings by about six months and presaged changes in the inflation rate. But with seasonal adjustments over the years, and changes in how the numbers are reported, I’m not sure the relationship is as obvious (during that 1950-80 time period) when looking at the numbers available today.

Why stop at 1980? The short answer is that is when NOW accounts were authorized.

7. October 2015 at 15:50

Rod,

That’s an interesting mix, but it doesn’t align as tightly with recessions compared with real M0 in YoY. Nothing’s perfect, but real MOM YoY has gone negative just ahead or in the early stages of every NBER-defined recession since the late-1950s. Not too shabby.

–Jim

7. October 2015 at 16:26

Jim,

If the Effective Reserves number generally flattened, or declined, for six months, a recession would follow. After it resumed growth, six months later the recession ended. But those were numbers generated in the 70’s using data that has since been significantly revised due to seasonal adjustments and other tinkering.

You are looking at more of a coincident indicator due to the fact that currency is in it and currency growth tended to be relatively stable, increasing slowly as inflation increased over the time period of the 50’s to 1980.

Again, the Fed had direct control over the level of reserves back then, so an easy argument could be made that they were affecting the economy directly, although I doubt they were aware of the mechanism at the time. I followed the Fed quite closely in the late 70’s and there was no indication of it anyway.

8. October 2015 at 03:26

Nick, I was joking about the coins. I do think they might be better than M2, but that’s weak praise.

8. October 2015 at 06:13

@ Sumner

That seems like a lot of mental exercise for a joke.

It’s your time.

🙂

The a priori notion that a change in the quantity of money will have an impact on price level seems to me on its face uncontroversial. (how much, what areas, etc. is a whole different topic and is controversial)

So that being given, it seems like your joke would be better served by at least a more complete definition of “what is money”.

“So if Friedman were alive today, how would he define money? The base still doesn’t work, as reserves also soared in 2008-09. Nor does M2. I don’t have a good answer, but I suspect that coins might be the best definition. ”

So assuming this is the point that “coins” became your joke, I do note that reserves are still at unprecedented levels.

🙂

I eagerly await the grand experiment that will yield reverse repo’s in an environment of rising prices. It should be fun to watch!

12. October 2015 at 18:24

Nick, My preferred definition of money is the monetary base. Second choice would be currency. Then coins.

13. October 2015 at 18:25

People, you can resolve all problems by accepting that money is neutral and the Fed has little or no influence over any real variable (Bernanke et al’s FAVAR paper), and, increasingly, over any nominal variable (Japan’s failed Abenomics, Lost Decades).

Or you can continue to construct epicycles that seem to justify the earth being the center of the universe.

14. October 2015 at 01:54

Everytime someone mentions 1/mps an angel loses it’s wings.