Mr. Friedman and the Classics

David Glasner just won’t let me rest and enjoy my weekend. He continues to insist that Keynes developed the theory that the demand for money is a function of the nominal interest rate (and other variables), and cites a 1935 article by John Hicks. So let’s take a look at a later article by Hicks, the one where he reviewed the GT and developed the famous IS-LM graphs:

And later this:

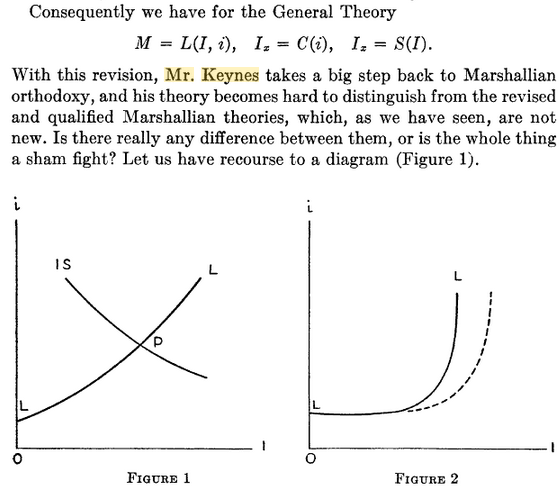

And later this:

And then this:

So the basic theory of the demand for money was already there with Lavington, Pigou, and others, it’s just that Keynes added the assumption of a liquidity trap at low interest rates. IS-LM is consistent with the classical view, it’s just that Keynes added a flat stretch to the LM curve.

It turns out that Mr Friedman had exactly the same view, that Keynes’ key innovation was absolute liquidity preference, and that the rest was consistent with previous models. Now that’s not to say the GT was a minor book. It has many interesting insights. And it put the pieces together more effectively than earlier writers. No one wrote down an IS-LM diagram before Keynes. I understand all that.

[Update: I should clarify that Keynes didn’t draw the graph either. But he spelled out the framework in a way that allowed Hicks to do so.]

But Friedman was not a Keynesian, and had a radically different way of looking at things. He was quite justified in claiming that the basic building blocks for his theory were there well before Keynes. Indeed Friedman’s approach owes much more to Fisher than to Keynes. Both Fisher and Friedman saw the price level as being the key variable that adjusted to restore monetary equilibrium, not the interest rate. To Friedman the interest rate was a sort of epiphenomenon. And both Fisher and Friedman visualized the Phillips curve model in terms of inflation affecting output, not output affecting inflation (as the Keynesians visualize it.) And so on.

Now David is much more of a scholar of economic history than I am, so I’m sure he’ll tell me I’m misinterpreting Mr. Keynes and the “Classics”.

PS. I also recommend looking at the comments at the end of David’s post. One in particular pretty much demolishes the claim that Friedman intentionally misrepresented the Chicago oral tradition.

Tags:

10. August 2013 at 10:13

In this comment by George Famon what clearly is demolished is Friedman’s claim that there was an alternative Chicago tradition of money demand. As Mr. Glasner says in repsonse to Famon:

“George, I think I see the distinction that you are making, but I am not sure why it matters. The demand for money is the demand for money and it is governed by the basic factors enumerated by Keynes in Chapter 17 of the GT, which Friedman, in essence, restates.”

“Friedman admitted that there was no Chicago oral tradition pertaining to the demand for money, but then introduced the Chicago quantity theory policy tradition as if that in any way was relevant to his own characterization of the quantity theory as a theory of the demand for money.”

“Your point about Friedman’s lecture notes from Mints’s class are certainly interesting and may the origin of Friedman’s mistake, but it only confirms that Friedman was more deeply influenced by Keynes than he admitted. Chicago was unique in many ways, but the point is that Friedman mischaracterized what was unique about it.”

http://uneasymoney.com/2013/08/06/hicks-on-keynes-and-the-theory-of-the-demand-for-money/#comment-21510

10. August 2013 at 10:33

“And both Fisher and Friedman visualized the Phillips curve model in terms of inflation affecting output, not output affecting inflation (as the Keynesians visualize it.)”

Here’s a relevant quote:

“We may, therefore, feel certain that changes in the price level do definitely foreshadow or anticipate changes in employment. Of course, this relationship might conceivably not be causal. So far as the statistics are concerned, instead of P’ being the cause of E, both might conceivably be caused by some third influence. Or it might be conceived that price change simply represents a forecast of good or bad business.

In fact, I have little doubt that both these views contain elements of truth. But as the economic analysis already cited certainly indicates a causal relationship between inflation and employment or deflation and unemployment, it seems reasonable to conclude that what the charts show is largely, if not mostly, a genuine and straightforward causal relationship; that the ups and downs of employment are the effects, in large measure, of the rises and falls of prices, due in turn to the inflation and deflation of money and credit.”

Irving Fisher, “A Statistical Relation between Unemployment

and Price Changes,” International Labour Review 13, no. 6 (June 1926): 785-92.

Earlier in the article Fisher gives an explanation for why price changes cause employment changes:

“The principle underlying this relationship is, of course, familiar. It is that when the dollar is losing value, or in other words when the price level is rising, a business man finds his receipts rising as fast, on the average, as this general rise of prices, but not his expenses, because his expenses consist, to a large extent, of things which are contractually fixed, such as interest on bonds; or rent, which may be fixed for five, ten, or ninety-nine years; or salaries, which are often fixed for several years; or wages, which are fixed sometimes either by contract or custom, for at least a number of months. For this and other reasons, the rise in expenses is slower than the rise in receipts when inflation is in progress and the price level is rising or the dollar falling. The business man, therefore, finds that his profits increase. In fact, during such periods of rapid inflation, when profits increase because prices for receipts rise faster than expenses, we nickname the profit-taker the “profiteer”. Employment is then stimulated-for a time at least.”

In short, wages are stickier than prices.

10. August 2013 at 11:33

On a slightly related note I’ve been trying to reconcile international profit measures which is no easy thing since the US uses the idiosyncratic National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) and the rest of the advanced world uses the System of National Accounts (SNA). The principle problems are that government corporations are part of the corporate sector, the major subdivisions in income are by sector and not by type of income, and there is no separate proprietorship sector in the SNA (partnerships are in the corporate sector and sole proprietorships are in the household sector). But here is what I have come up with for the US closer to SNA standards:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=132045&category_id=0

From top to bottom you have Gross Operating Surplus (GOS), Net Operating Surplus (NOS), Corporate NOS, Corporate Profits and Corporate Profits After Tax. Everything is adjusted for the GDP implicit price deflator.

In particular note that the measures of corporate surplus started declining before the start of every recession with the exception of the 1974-5 and 1981-2 recessions, and in some cases they started to decline well before the recessions started. (And as long as I’m on the subject note that Corporate NOS only just set a new record in the first quarter.)

So I basically see this as a confirmation of Fisher’s intuition in that corporate surplus leads the economy.

Now this data is more easily comparable to data for the eurozone and the UK, although their data is not seasonally adjusted. Japan unfortunately does not provide quarterly data for the corporate sector. Furthermore Japan produces quarterly income data with a one year lag which is enourmously frustrating, and similarly to the European data, it is not seasonally adjusted.

I’ve made the seasonal adjustments and I can tell you the other three major advanced currency areas are doing terribly. Corporate NOS was off by 21.6% and 29.6% from peak in the eurozone and the UK in 2013Q1 and 2012Q4 respectively (previous peaks in 2007Q4 and 2008Q1 respectively) and both have been trending downward since 2010Q4. Japan’s NOS was off by 15.9% from previous peak in 2007Q1 as of 2012Q1 and had been trending downward since 2010Q3. This certainly explains why the US stock market is doing so well and the European stock markets are still well off peak to virtually comatose.

I have tons of data on corporate sector debt and business bankruptcies/insolvencies that paint a similar picture. The US is healing, the eurozone is collapsing, the UK is in some peculiar twilight zone and Japanese data is woefully inadequate and/or out of date.

10. August 2013 at 13:09

Mike, That may or may not be true, but it’s not clear to me why it matters.

Mark, Thanks for the very interesting data. I wonder how long it will be before the Japanese get around to reporting Q2 GDP.

10. August 2013 at 14:16

It matters because it’s the whole basis to prove that Friemdan wasn’t in some sense a ‘closet Keynesian’ on the issue of the demand function for money. He had appealed to this alternative Chicago tradition to prove that he wasn’t a Keynesian.

As to your Hicks quotes here the implication here about Keynes couldn’t be more different than the implication of the quotes of Mr. Glasner that were also of Hicks. So at best how do you decide how to choose between them?

Your quote has Keynes taking a step back to the Marshallian tradition. However, David quotes him thus:

“My suggestion may, therefore, be reformulated. It seems to me that this third theory of Mr. Keynes really contains the most important of his theoretical contribution; that here, at last, we have something which, on the analogy (the approximate analogy) of value theory, does begin to offer a chance of making the whole thing easily intelligible; that it si form this point, not from velocity of circulation, or Saving and Investment, that we ought to start in constructing the theory of money. But in saying this I am being more Keynesian than Keynes [note to Blue Aurora this was written in 1934 and published in 1935].”

http://uneasymoney.com/2013/08/06/hicks-on-keynes-and-the-theory-of-the-demand-for-money/

10. August 2013 at 15:55

Sadowski, you just knocked something loose.

“In short, wages are stickier than prices.”

This is true, until prices hit zero.

I keep trying to get econ folks to model the macro transform of an economy with scarcity vs. one without it.

It’s the biggest thing EVER in Economics.

Every year, consumption of infinite digital goods / services grows relative to scarce atomic goods / services.

As such, as prices go to zero, there is an exact moment when wages ARE less sticky than prices.

Going below zero on FREE SHIT is far harder than the ZLB.

Someone ought to be discussing that Free lower Bound (the LBF) is real while the ZLB is not.

11. August 2013 at 01:06

Keynes also wrote several articles in 1936 and 1937 which criticizes Hicks’ view of The General Theory. Keynes basically says the way Hicks viewed his theory was wrong.

There’s a difference between the Keynesians and Keynes; Keynes’ viewpoints and ideas are not what is considered “Keynesian”.

“The alternative theory held by … Mr. Hicks, and probably by many others, makes it to depend, put briefly, on the demand and supply of credit or, alternatively(meaning the same thing), of loans, at different rates of interest. Some of the writers(as will be seen from the quotations given below) believe that my theory is on the whole the same as theirs and mainly amounts to expressing it in a somewhat different way.’Nevertheless the theories are,I believe, radically opposed to one another. The following quotations will explain the point at issue.”

The paper is titled The Alternative Theories of the Rate of Interest.

Even Hicks would admit that IS/LM is a poor interpretation of Keynes’ work. Please don’t cite IS/LM as Keynes; you can look through everything that Keynes wrote and IS/LM is clearly not Keynes’ idea. Look through this paper and other papers that Keynes wrote. Hell, even go through TGT again, you’ll realize it’s really just not true. Even Hicks ended up coming to the same conclusion.

That being said, you shouldn’t cite Hicks’ 1935 paper without citing Keynes 1937 reply when Hicks didn’t even understand what Keynes initially wrote(Hicks even admitted as such).

11. August 2013 at 01:08

When trying to understand Keynes’ view of finance, a traditional supply/demand framework using equilibrium is just not possible. He starts from different assumptions, so using such a framework is violating Keynes’ starting assumptions and will lead to an incorrect view and incorrect results.

11. August 2013 at 01:11

In fact, I’d argue that what Keynes’ theory about interest rates is much closer to what your ideas say than what is considered Krugman. What would be stimulative now? A steeping yield curve from increasing inflation/growth/inflationary expectations/growth expectations, right? That’s central to what Keynes actually says and talks about in several of his works. He mainly expounds on that after The General Theory.

11. August 2013 at 01:12

*considered Keynesian(Krugman).

That asterisk should replace the end of the first sentence in my previous comment on this page.

11. August 2013 at 06:17

Mike, You asked:

“So at best how do you decide how to choose between them?”

Normally you’d take the more recent quotation.

Suvy, I disagree. I think Hick’s IS-LM does accurately summarize the key points in the GT. Many other modern Keynesians agree. I’m sure Krugman would agree.

11. August 2013 at 09:54

Prof. Sumner,

Keynes clearly felt the opposite. He specifically says so and details why in the paper above. Most of those Keynesians haven’t even read Keynes(ex. like them blaming inflation on labor unions).

11. August 2013 at 10:54

[…] 3: More links. Money Illusion, Money illusion, Nick Rowe, Tyler Cowen, Romer and Romer, Krugman, […]

11. August 2013 at 14:12

[…] of Chicago quantity theorists lacked any foundation. Although some people, including my friend Scott Sumner, seem resistant to acknowledge these points, I don’t think that they are really very […]

11. August 2013 at 15:53

Friedman devoted only 11 pages to the people and politics of the origin of the Fed in his book “A Monetary History.”

Too bad, because this helped fuel the general misconception that the Fed was designed for altruistic, technocratic reasons.

11. August 2013 at 18:00

[…] Sumner won’t let go. Scott had another post today trying to show that the Cambridge Theory of the demand for money was already in place before Keynes […]

12. August 2013 at 01:55

Although this isn’t directly related to the topic…Professor Sumner, have you read Sir John R. Hicks’s “explanation” piece for IS/LM that was published in the Journal of Post Keynesian Economics?

http://www.jstor.org/stable/4537583

I read through it once, and I felt that although Sir John R. Hicks was right to acknowledge the limitations of his IS/LM model, I couldn’t help but get the feeling that he wrote that piece in a frame of mind that was overly-self-critical. I also couldn’t help but get the impression that he was depressed.

12. August 2013 at 10:28

Suvy, Keynes was on both sides of virtually every issue during his life. So you can find a Keynes quote to prove anything. I have quotes that he supports the gold standard. In any case, of course he’d reject IS-LM, it makes the book seem like a trivial improvement. And if it turns out IS-LM is wrong, as the model in the Treatise was, then it blows him right out of the water.

Blue, No, I haven’t read it.

12. August 2013 at 14:02

“I have quotes that he supports the gold standard.”

But this would not be a fair interpretation of Keynes’ work taken as a whole, and neither is IS/LM. IS/LM was actually developed independently by Hicks, as well as people like Dennis Roberts, at the time Keynes was writing the general theory. It is also fundamentally incompatible with the general theory, primarily due to the fact that it excludes a role for irreducible uncertainty.

“And if it turns out IS-LM is wrong, as the model in the Treatise was, then it blows him right out of the water.”

Funny, as John Hicks admitted IS/LM was wrong in 1980 in “IS/LM: An Explanation”, and he didn’t seem to think this ‘blew Keynes out of the water’ at all.

13. August 2013 at 05:14

Unlearningecon, I strongly disagree, IS-LM gets at the essence of the GT. And your point about 1980 is a complete non sequitor. I doubt Hicks said IS-LM is “wrong” That would be a bizarre statement.

If he didn’t think it was useful, it’s probably because he thought it didn’t fully capture Keynes’s insights.

13. August 2013 at 11:08

Scott, you could just read the paper and you’d see. Here is Hick’s argument in a nutshell:

IS/LM relies on a given set of expectations to determine decisions about investment and money holding, so the time period must be short, else expectations will be continually changing and so will both curves, rendering the static nature of the model unsound. However, if the model is the short term, this creates another problem: there is little room for irreducible uncertainty, which was the necessary condition for liquidity preference to exist. Hence, there is no liquidity preference and no LM curve, and no time period which renders IS/LM valid.

There are many alternative interpretations of Keynes out there, expounded by people like Geoff Tily, Paul Davidson and Michael Emmet Brady, as well as Keynes’ biographer Robert Skidelsky. None of them rely on IS/LM, and many give good reason to believe Keynes didn’t either. You can disagree with IS/LM, or with Keynes, or even that this is a worthwhile debate, but it’s simply not true that IS/LM gets at the essence of Keynes’ theory.

13. August 2013 at 18:52

[…] it was hijacked by Paul Krugman, Scott Sumner and I were having a friendly little argument about whether Milton Friedman repackaged the Keynesian […]

14. August 2013 at 06:57

Unlearningecon, I’m well aware of the fact lots of economists don’t think the IS-LM model captures the GT. But the smartest macroeconomists out there think it does. That paragraph of Hicks makes no sense to me, he wrote much better when he was young. Models always abstract from reality. I don’t see where failing to capture “uncertainty” in any way changes the fact that IS-LM does capture the basic model of the GT.

If I was convinced otherwise, that the GT was not basically IS-LM, then I’d throw the GT in the trash as it would be so poor at explaining Keynes’s ideas that it would be worthless. If not IS-LM, then gibberish.

14. August 2013 at 09:53

Scott, with regard to IS/LM, you’re essentially relying on an argument from authority while ignoring the biggest authority of all, John Hicks, the creator of IS/LM. He didn’t think it came close to capturing the essence of Keynes, and there is a reason why.

And it’s clear that you haven’t read the paper that UL has referenced twice now, as that paragraph “of Hicks” was just a summary by UL (and a good one at that), it’s not actually in the paper. I think you would be better off if you read the paper, to get a better perspective on why Hicks and Post Keynesians don’t think IS/LM “captures the essence of Keynes” at all.

I would also advise checking out the people UL referenced above, as they (and other economists) could somehow make sense of the GT without relying on IS/LM. In other words, they saw a lot more in the GT than some basic IS/LM framework and it amounted to a bit more than “gibberish”.

14. August 2013 at 10:30

Rousseau, I have read some of the Post Keynesians and disagree with almost everything they have to say on monetary policy. Life’s short and I don’t even have time to read all the material I’d like to read. I don’t plan to spend more time reading post-Keynesians. If I had more time (I don’t) I’d read more of the pre-war macroeconomists.

Economists could get far more out of rereading the Tract and the Treatise than the GT, which is an inferior book.

14. August 2013 at 10:50

Scott, fair enough. Obviously from a monetarist perspective, one we feel more inclined to like the Tract and the Treatise than the GT. And even though you may disagree with Post Keynesians on monetary policy, I still think you might find some great value in their interpretations on Keynes, as they are very insightful. For instance, I think Keynes’ emphasis on uncertainty you might find interesting.

Anyway, taking your time into consideration, rather than look over the vast amount of literature on Keynes, you could check out this blog, search around a bit, and read a few short posts to get a better sense of what I am talking about. Just a friendly suggestion.

http://socialdemocracy21stcentury.blogspot.com/search?q=John+Maynard+Keynes

14. August 2013 at 17:39

Rousseau, Thanks for the link. FWIW when Keynes used the term “confidence” it’s pretty clear to me that he meant something close to what we would today call “expected NGDP growth.” A sharp decline in expected NGDP growth, such as late 2008, would be seen by Keynes as a fall in confidence.

15. August 2013 at 07:35

“Unlearningecon, I’m well aware of the fact lots of economists don’t think the IS-LM model captures the GT. But the smartest macroeconomists out there think it does.”

Smart people believe a lot of things: religion, the earth was flat, etc. Doesn’t make ’em so.

“That paragraph of Hicks makes no sense to me, he wrote much better when he was young.”

Lol, that was me attempting to condense his paper into a paragraph, and apparently failing. But the key point is about changing expectations: IS/LM takes expectations as a given and this creates problems for the model.

“Models always abstract from reality.”

That’s not a response to Hick’s argument; Hicks argues against IS/LM on the grounds that it is internally inconsistent.

“I don’t see where failing to capture “uncertainty” in any way changes the fact that IS-LM does capture the basic model of the GT.”

Because uncertainty is Keynes’ condition for liquidity preference to exist.

As Rousseau said, there are many, many ways to make Keynes make sense without accusing him of ‘gibberish’, which is a big claim to make for one of the “smartest macroeconomists” of all time. Maybe you’re not interested in this, which is fine, but don’t try to discredit Keynes this way when you won’t even read a paper on the matter.

15. August 2013 at 11:20

Unlearning econ, You are misrepresenting what I said. I never accused Keynes of writing gibberish. I understand what he was trying to say in the GT.

The fact that liquidity preference exists due to uncertainty (of course there are other factors too) does not mean it must be in a particular model. There are shifts in LM and movements along LM.

And I’m not too lazy to read post-Keynesian stuff, I’ve read lots of it and given up. There is a difference.

24. August 2013 at 04:01

Although this is belated, I don’t think that Dr. Michael Emmett Brady (you keep misspelling his middle name, Unlearningecon!) considers himself a part of the Post Keynesian economics movement…