Money and Inflation, Pt 3 (The Quantity Theory of Money and the Great Inflation)

Here’s my Russ Roberts Podcast. Patrick sent me my AEI presentation and my Larry Kudlow interview (67 minute mark, 3/23/13).

There are two aspects of fiat money that make the supply and demand for a fiat currency differ from the commodity money model:

1. The government has almost unlimited control over the stock of currency, and can produce currency at near zero cost.

2. The demand for money becomes unit elastic, in response to changes in the value of money (1/P).

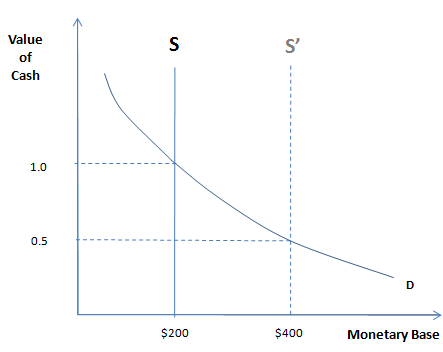

Here’s how the money supply and demand graph looks for fiat currency:

Monetary policy has switched from influencing the demand for the MOA (under the gold standard), to a policy of influencing the supply of the MOA (although money demand is also affected by Fed policies.) The Fed can shift the supply curve to the left or right via open market operations or discount loans. Thus the “supply curve” is actually a policy tool, representing the quantity of base money.

In the past I used to teach the quantity theory of money with a “helicopter drop” example, but I now see that won’t work—people get the wrong message. Traditional OMOs also confuse people. More specifically:

1. Some Keynesians believe it matters a lot whether the currency is introduced via a “helicopter drop” or OMOs. The term ‘helicopter drop’ actually refers to combined monetary/fiscal expansion. Money dropped out of helicopters is sort of like “welfare” payments, and it’s also an expansion of the money stock. So it’s like paying for a new entitlement program by printing cash and spending it. But these Keynesians are wrong. The fiscal effects are utterly trivial as compared to the monetary effect, at least during normal times. Increasing the base by 0.2% of GDP during normal times is a big deal. Increasing debt held by the public by 0.2% hardly matters at all.

2. Some Austrians worry about “Cantillon effects,” which means they think it’s important to consider who gets the money first. (Although the term also has other meanings). They assume that that lucky group will boost its spending. Yet the money is not given away, it’s sold at market prices. So the person getting the money first is not significantly better off, and hence has little incentive to buy more real goods and services.

Both errors share something in common—the notion that money injections matter because “people with more money will spend more.” But this subtly confuses wealth and money. In everyday speech we might say; “a billionaire buys a big yacht, because he has lots of money.” But we really mean he has lots of wealth. The billionaire might have very little cash. So if we are truly going to understand the pure effects of monetary injections (without fiscal or Cantillon effects), we have to consider a form of injection that doesn’t appear to make anyone “better off,” so that people would have no obvious reason to go out and buy more stuff.

I’d like to assume that money is injected according to the following formula: Suppose there are 100 million Americans that get substantial checks from the government each year (more than $200). These include tax rebates, veterans benefits, unemployment insurance, government worker salaries, Social Security, etc. A cross section of America. The Fed wants to increase the base by $20 billion this year. Have the Treasury pay each of the 100 million Federal check recipients the first $200 due to them in cash, and the rest by check. In this case people are not getting any additional money, it’s just that some of it comes in the form of cash rather than the usual checks. If the Fed had decided not to increase the base, the extra $200 would have been paid by check. That is the essence of monetary policy, with no distracting bells and whistles.

People don’t want to hold that much extra cash, so they’ll get rid of it. But how? Obviously not by burning it. Now we come to the concept that lies at the heart of money/macro—the fallacy of composition. Individuals can get rid of the cash they don’t want, but society as a whole cannot, at least not in nominal terms. How do we reconcile that seeming paradox?

Take an example where the Fed doubles the currency stock, from $200 to $400 per capita (shown in the graph.) How do we reach a new equilibrium? In the short run prices are sticky, and short term interest rates might fall. But over time prices will adjust, and the public will reach a new equilibrium where they are happy holding $400 per capita. How much do prices have to rise for supply to equal demand at the original interest rate?

If we assume that people care about purchasing power rather than nominal quantities, then prices must double, so that the purchasing power of the stock of cash returns to its original level. Say that people used to hold enough cash to make one week’s worth of purchases ($200.) Then prices must rise until one week’s worth of purchases costs $400. In other words prices rise in proportion to the rise in the currency stock. And that means the demand curve for the MOA is unit elastic. In contrast, when silver (or gold) was the MOA, the demand for those assets was not unit elastic. Currency is special. Its only value is its purchasing power—it has no industrial uses at all (unlike gold.)

The assumption of a unit elastic demand for currency leads to the Quantity Theory of Money. If you double the money supply, the value of money will fall in half, and the price level will double. Of course this assumes the demand for money does not change over time. But money demand does change. It would be more accurate to say; “a change in the money supply causes the price level to rise in proportion, compared to where it would be if the money supply had not changed.” But even that’s not quite right because (expected) changes in the value of money can cause changes in the demand for money. So all we can really say is:

One time changes in the supply of money cause a proportionate rise in the price level in the long run, as compared to where the price level would have been had the money supply not changed.

That’s because one time changes in the money supply probably don’t shift the real demand for money in the long run. This is a somewhat weaker version of the QTM, but is the most defensible version. In my view the QTM is most useful when there are large changes in the supply of money, and/or over the very long run. Especially when there are large changes in the supply of money, year after year, over a very long period of time. In other words, international data over a long period during the global Great Inflation. Robert Barro’s macro text (4th ed.) has the perfect data set for thinking about the QTM; 83 countries, over roughly 30 years, when inflation rates were very high and varied dramatically from one country to another. Here are the top 10 and the bottom 10 on the list:

Country MB growth RGDP growth Inflation Time period

Brazil 77.4% 5.6% 77.8% 1963-90

Argentina 72.8% 2.1% 76.0% 1952-90

Bolivia 49.0% 3.3% 48.0% 1950-89

Peru 49.7% 3.0% 47.6% 1960-89

Uruguay 42.4% 1.5% 43.1% 1960-89

Chile 47.3% 3.1% 42.2% 1960-90

Yugoslavia 38.7% 8.7% (FWIW) 31.7% 1961-89

Zaire 29.8% 2.4% 30.0% 1963-86

Israel 31.0% 6.7% 29.4% 1950-90

Sierra Leone 20.7% 3.1% 21.5% 1963-88

. . .

Canada 8.1% 4.2% 4.6% 1950-90

Austria 7.1% 3.9% 4.5% 1950-90

Cyprus 10.5% 5.2% 4.5% 1960-90

Netherlands 6.4% 3.7% 4.2% 1950-89

U.S. 5.7% 3.1% 4.2% 1950-90

Belgium 4.0% 3.3% 4.1% 1950-89

Malta 9.6% 6.2% 3.6% 1960-88

Singapore 10.8% 8.1% 3.6% 1963-89

Switzerland 4.6% 3.1% 3.2% 1950-90

W. Germany 7.0% 4.1% 3.0% 1953-90

Homework for today:

Answer the following 5 questions and you’ll understand the QTM:

1. Does the “eyeball test” provide more support for the QTM in the low or the high inflation countries? What does this tell us about its actual applicability to each group? How does its relative applicability to each group depend on which of the definitions of the QTM (discussed above) is used?

2. In 71 of the 83 countries the money growth rate exceeds inflation, and in 12 the inflation rate exceeds the money growth rate. Explain why the ratio is so lopsided.

3. The gap between money growth rates and inflation exceeds 10% in only one of the 83 countries (Libya–not shown.) Why does the gap rarely exceed 10%?

4. Do most of the twelve cases where inflation exceeds money growth occur in low or high inflation countries. Explain why.

5. Explain what sort of inflation data would better explain the gap: average inflation rates, the change in the inflation rate, or changes in the expected inflation rate.

I’ll answer tomorrow in the next post. The commenter with the best set of answers gets a gold star.

Tags:

25. March 2013 at 07:40

To repeat.

You understand neither Austrian macroeconomics, nor the Cantillon Effect.

This does *NOT* address Hayek’s monetary economics and macroeconomics.

Become competent in the economics *THEN* analysis it and talk about it.

A professor would never let a freshman do this backwards taking up his class time talking endlessly and critically about things he hasn’t done any work to gain minimal scientific competence to discuss.

Really. Do the work. The engage the science. Otherwise, spare us.

Scott writes,

“Some Austrians worry about “Cantillon effects,” which means they think it’s important to consider who gets the money first.”

25. March 2013 at 07:46

Scott, to talk seriously about Hayek & economists or journalists using Hayek’s scientific work, you need to engage the monetary economics of finance, banking and money substitute assets — eg endogenous money and the relation of the Federal Reserve to that.

And then connect that up to the logic of choice across time involving the valuation of heterogeneous and interconnected production goods of alternative lengths, output and kind.

*NEVER* seen you do that.

25. March 2013 at 09:01

Scott,

I have some question on

“Have the Treasury pay each of the 100 million Federal check recipients the first $200 due to them in cash, and the rest by check. In this case people are not getting any additional money, it’s just that some of it comes in the form of cash rather than the usual checks:

– If the government had previously been raising the money for the checks via a tax and they continued with the same level of tax even when the $200 per person is paid in newly minted money – will this still be inflationary? (in this case the new money will in effect be used to reduce the govt deficit or lead to a larger balance being held in a treasure acct somewhere).

– If the govt didn’t print new money but just reduced the tax by the equivalent amount and continued to send out checks won’t that be just as inflationary as in the money printing case ? (not sure this would be legally permitted – but if they did it anyway and just allowed the acct funding the checks to go into deficit).

25. March 2013 at 09:36

(1) So the QTM, as I remember it, takes into account the fact that MB increases alongside production increases are not inflationary, so the correlation should be roughly between MB expansion and (RGDP+inflation). It seems to me that that shows an extremely high correlation for both high and low inflation c countries. Still, the correlation obviously looks better for high inflation countries. If you insist on ignoring RGDP growth as per the definition above then its much better for high inflation countries – obviously.

(2)If you ignore RGDP growth it causes the correlation to break down at low inflation, as it works only when MB growth>>RGDP growth.

(3)Because RGDP growth rarely exceeds 10%.

(4)Low, RGDP growth is much more significant relatively when RGDP roughly equal magnitude to inflation.

(5) None of the above? I mean you could make an argument that there was a persistent gap between expected inflation and actual expansion of the monetary base, but that such a gap should persist in one direction for fifty odd years strains credibility. I would guess that the next biggest effect was structural: changes in capital flow and associated willingness of foreigners to hold your currency. My intuition is that a lot of Europeans held quite a lot of wealth in dollars and Swiss francs through the 1920-1950 period, and slowly sold those holdings and brought the money back as Europe recovered. US and Switzerland stand out has having more inflation than you would guess, and they are the archetypal haven currencies. Some of the others like Zaire and Sierra Leone experienced massive capital flight due to social unrest.

25. March 2013 at 12:18

What is the demand for money when seignorage is negative?

25. March 2013 at 12:29

Ssumner, I don’t understand why do you equate the Keynesian reasoning with the Austrian one, a helicopter drop is different from OMO precisely because a helicopter drop is increasing people’s wealth contrary to OMO, so this would usually boost AD. And not because of some fallacy of who receives the money first …

Now obviously keeping in mind the sumner critique this will only be true if the monetary authority is not sterilising this, which can happen for instance on the ZLB as monetary policy becomes less effective(note the term less and not not effective as it would still be effective but less).

I guess the big debate is whether the MB or the level of interest rates that determines the price level…

As for the questions:

1) on the high inflation sample, mb seems correlated with inflation, while on the low inflation sample, it seems correlated with NGDP growth. Low inflation sample makes sense, for the high inflation case to make sense, it means that velocity has been going up, which is I guess explained by a loss of confidence from the people. So when they see high inflation they expect even higher inflation etc …

2) If we assume positive RGDP growth, you would expect mb to increase more which explains the finding.

3)for the gap to be that big, either RGDP growth has to be >10% which is rare, or velocity going down by 10% which is quite difficult to happen.

4) In high inflation countries, this goes in tandem with question 1, in high inflation countries, expected inflation seems to be quite high which is driving velocity up and inflation up.

5) I would say the expected inflation.

25. March 2013 at 14:35

Love “Homework for today”! But commenters phil and Georges beat me to it, so I don’t have much to add. FWIW, my answers:

1. (a) High inflation; (b) there’s some additional factor of a couple percent, which becomes less significant as all the numbers get bigger, but more significant if NGDP is low; (c) for all three of the definitions, high inflation is a better match, because you hope that MB growth = NGDP growth, and that is closer in the high inflation countries. But velocity changes, and we don’t know the path of velocity for each country during the period.

2. If velocity is stable, MB growth = inflation + RGDP growth, so therefore MB growth > inflation. Velocity can either go up or down or be stable. In order for inflation > MB growth, velocity would have to skyrocket, which is unlikely.

3. With stable velocity (on average, over the long term), it would require RGDP growth > 10%, which is very rare.

4. (a) high inflation; (b) with big numbers, velocity only needs to rise a little bit, in order for inflation to exceed MB growth. With low inflation, it would require huge velocity growth to get above MB growth (since you need to make up for the RGDP component of NGDP as well).

5. Changes in inflation expectations. The missing data is velocity, and we need to at least get some indirect data in order to get a hint on what is happening to velocity.

25. March 2013 at 14:43

The old-school QTM is kind of a self-fulfilling prophecy, right? The idea being: if you consistently and moderately increase M, then V will remain stable over the long run (because NGDP expectations will remain stable), so NGDP will grow consistently and moderately. So market monetarism, if successful in stabilizing NGDP expectations, would collapse into QTM (?)

25. March 2013 at 16:33

Rob, Inflation depends on monetary policy, taxes play almost no role. So the helicopter drop is only a tiny bit more inflationary than an OMO.

George, If there is no sterilization the fiscal stimulus will increase the price level, but the size of the increase will be utterly trivial compared to monetary stimulus–that was my point.

Josh, Maybe, but that’s not certain.

25. March 2013 at 16:41

Biotech companies, take note! Being a lame duck enables regrowth of missing spinal tissue:

Bernanke on QE: “Because stronger growth in each economy confers beneficial spillovers to trading partners, these policies are not ‘beggar-thy-neighbor’ but rather are positive-sum, ‘enrich-thy-neighbor’ actions,” he aid.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/03/25/ben-bernanke-fed-world-economy_n_2949959.html

25. March 2013 at 17:02

1) Both the high-inflation and the low-inflation countries support QTM

MV = YP

d(MV) / MV = dM/M + dV/V

d(YP) / YP = dY/Y + dP/P

%cange in M + %change in V = %change in P + % change in Y

if v is nearly constant.

Money growth = NGDP growth.

2) Money growth + velocity change = real growth + inflation

If velocity change is less than real growth (which should be the case most of the time) then Money growth is greater than inflation.

3) example is not shown… For the differential between money growth and inflation to exceed 10% either RGDP change or velocity change must be extreme.

4)This relationship:

%cange in M + %change in V = %change in P + % change in Y

Is only linear in for moderate movements in M, V, P and Y.

When changes become sufficiently large in any one of the variables the affect on the error terms is multiplicative.

5) What gap?

Money growth is correlated with changes in prices. (iflation is a change in the price level) Changes in inflation would be a second derivative. So of the three choices given Average inflation rate is the only one that is aplicable. Had you offered the level of expected inflation, I may have to consider that.

25. March 2013 at 17:20

“But these Keynesians are wrong. The fiscal effects are utterly trivial as compared to the monetary effect, at least during normal times. Increasing the base by 0.2% of GDP during normal times is a big deal. Increasing debt held by the public by 0.2% hardly matters at all.”

I gather your criticism does not apply to endogenous money theorists, since these argue that the monetary effect takes place only on the initiative of the private banking system, i.e. broad money expands before, not after base money does.

“2. Some Austrians worry about “Cantillon effects,” which means they think it’s important to consider who gets the money first. (Although the term also has other meanings). They assume that that lucky group will boost its spending. Yet the money is not given away, it’s sold at market prices. So the person getting the money first is not significantly better off, and hence has little incentive to buy more real goods and services.”

The market price is affected by the expectation that a monetary injection will happen. In as far as the Fed’s actions are predictable (which to a certain extent they always are), these will get front-run by the market. So the Fed typically purchases assets at a premium for being predictable and the successful Fed predictors pocket some if not all of the proceeds of seigniorage.

25. March 2013 at 17:23

1. QTM works better in high inflation countries.

Stable MB growth is a better target in high inflation countries than low inflation countries.

It doesn’t matter if you are Keynesian or Austrian.

2. Money growth exceed inflation in most countries because expected nflation and velocity were both falling.

3. The power of compounding. 10% for 3 decades is over 1600%. You would need massive changes in velocity.

4. 5 of the 12 cases of inflation exceeding money growth occur in the top ten inflation cases listed. The hot potato effect is powerful stuff; it really drives up velocity.

5. The change in inflation rate. High inflation expectations increase velocity, and low inflation expectations lower velocity. The hot potato, again.

When do I get my gold bar?

25. March 2013 at 17:24

5. I meant change in inflation expectations.

And dang it, it’s a gold STAR, not a gold BAR! Oh well.

25. March 2013 at 17:40

“Both errors share something in common””the notion that money injections matter because “people with more money will spend more.” But this subtly confuses wealth and money. In everyday speech we might say; “a billionaire buys a big yacht, because he has lots of money.” But we really mean he has lots of wealth. The billionaire might have very little cash. So if we are truly going to understand the pure effects of monetary injections (without fiscal or Cantillon effects), we have to consider a form of injection that doesn’t appear to make anyone “better off,” so that people would have no obvious reason to go out and buy more stuff.”

Scott, I understand that under the Fed’s “normal” strategy, it injects solely liquidity and not capital into the market by doing monetary injections. But things are markedly different when highly unconventional circumstances and actions like the current ones are in question.

When the Fed first buys up government debt and then rips up the paper, you can not argue that the government is no better off than before the Fed’s intervention. It’s debts have been forgiven. That is capital injection, not liquidity injection.

My suspicion is that the extreme debt growth prior to the 2008 crisis has given rise to a situation where the Fed will end up doing something equivalent to ripping up debt in order to counter debt-deflationary pressure. It has to get rid of debt to counter deflation, so it will have to rip up debt paper or do something equivalent. Most likely it will keep its balance sheet in its expanded state forever. It will roll over debts on the balance sheet perpetually and return any interest on it to the government. This is equivalent to ripping up the paper. It is capital injection, not liquidity injection.

The “monetary effects” you are hoping for will never be brought about by monetary injections, because they have already occurred in anticipation of the injections, prior to these, not as a result of these.

25. March 2013 at 17:55

Steve, It’s actually six of the 12 cases in the top 10, and 8 of the 12 in the top 13 countries.

Rademaker, I mostly disagree. The government pockets the seignorage, not Fed predictors. And I don’t expect the Fed to be ripping up any paper, except worn out dollar bills.

Answers tomorrow.

25. March 2013 at 18:02

Hi Scott,

I listened to the AEI presentation and it seemed you implied that Australia follows NGPD targeting. It was only after listening to Econtalk that I understand you to mean that Australia did well in the Global Financial Crisis because luckily (i.e. China needs coal and iron ore) it had a higher NGDP, rather than because it targeted NGDP. Is this correct?

I thought you might like Glenn Stevens (RBA Governor) response after being questioned on NGDP targeting:

“I think I can claim that I did more than most people to build the current framework. I think it works very well and I would be very loath to move off it.”

As a worldwide authority on NGDP targeting does this seem a reasonable response that will affect the lives of millions of people? 🙂

Glenn Stevens later says: “in a case where we have, say, very large terms of trade swings that make nominal GDP rise 10 per cent one year and go down 10 the next year we would have to have a way of figuring out how to handle that if we were targeting nominal GDP”

I only completed second year economics so I am having trouble understanding fully what he means. Do you think very large terms of trade swings is a good reason to not use a NGDP target?

Thanks for the blog. I am always learning when I come here.

25. March 2013 at 18:07

Thanks Scott, really enjoyed this post, very informative.

25. March 2013 at 18:13

“It’s actually six of the 12 cases in the top 10”

I count five, but maybe I’m missing something.

Brazil 77.4% 5.6% 77.8% 1963-90

Argentina 72.8% 2.1% 76.0% 1952-90

Uruguay 42.4% 1.5% 43.1% 1960-89

Zaire 29.8% 2.4% 30.0% 1963-86

Sierra Leone 20.7% 3.1% 21.5% 1963-88

25. March 2013 at 18:26

“Rob, Inflation depends on monetary policy, taxes play almost no role. So the helicopter drop is only a tiny bit more inflationary than an OMO.”

My question relates to why switching a regular payment from check to cash will be inflationary at all , even if the cash is newly printed.

If base money is defined as bank reserves + paper money then the new cash will increase the money supply , but apart from the small degree to which holding cash rather than having money in the bank increases the propensity to spend then the result of your example will be a decrease in V to match the increase in M , won’t it?

So unless the govt reduces taxes as a result of this policy or spends the money it saves on something else it will not have a major effect on the price level.

Am I missing something ?

25. March 2013 at 18:30

All right, I’ll take a stab 🙂

1) High. The numbers are large and often strongly correlated, almost eerily so.

2) Productivity gains are deflationary. This ratio may also be affected by population changes over time.

3) All else being equal, they should approach each other over time, assuming inflation is being calculated correctly and velocity varies around a mean.

4) I pasted these into Excel, created a column for the difference, and sorted lowest to highest. 5 of the 6 were high inflation.

5) Expectations uber alles.

6) Isn’t a little inconsistent of you to support the gold star standard? 🙂

25. March 2013 at 20:40

“2. The demand for money becomes unit elastic, in response to changes in the value of money (1/P).”

I see prices quoted in terms of currency and demand deposits and as long as there is 1 to 1 convertibility, MOA = MOE = currency plus demand deposits.

Let’s try it this way. $800 billion in currency, $200 billion in central bank reserves, and $6.2 trillion in demand deposits. Next, demand deposits go to $13.2 trillion. The others stay the same. What is the most likely scenario for prices?

Next, nobody wants currency, so there is $0 in currency, $200 billion in central bank reserves, and $14.0 trillion in demand deposits. I can see very little change in prices even though currency is $0 because MOA = MOE still = $14.0 trillion.

The point is the M in MV = PY should be MOA = MOE = currency plus demand deposits.

25. March 2013 at 23:15

Rob, I believe this is biggest monetarist point, the hot potato effect. If someone holds cash in his hand, he wants to get rid of it like if you we’re holding a hot potato, so you will want to give it away driving inflation up.

Scott, this series of posts are very informative, thanks!

26. March 2013 at 00:17

1a. The eyeball test provides more support in the high inflation countries, at least

if we just look at the monetary base and inflation.

1b. It works very well in both groups, however it seems more applicable to the high inflation countries – there is no discussion whether the inflation in those countries were caused by high base growth.

2. Efficiency gains lower costs for a given base, and population growth increases total real money demand. This means that real gdp growth will reduce the price level holding the base constant. For low inflation countries this effect is relatively large, and even in high inflation countries there will be significant real growth over such a long period, making the distribution skewed.

3.

Because RGDP growth rarely exceeds 10%, and real money demand is usually pretty stable in the long run. Also, the Taylor approximation for growth rates break down.

4.

Inflation exceeds money growth in none of the low inflation countries shown, and in 5 of 10 of the high inflation countries. Because of RGDP growth, money demand has to decrease on top of the increase in money supply for inflation to outpace base growth. In low inflation countries this effect has to be extremely large. For high inflation countries this can happen because:

– The RGDP effect is relatively small

– Money demand becomes unstable at high inflation rates. The opportunity cost of holding money (the nominal interest rate) increases 1 to 1 with expected inflation (or NGDP, but the distinction is not important for high inflation countries). In an inflationary environment, expected inflation will be very high as well, and very unpredictable.

Money demand decreases because of the high opportunity cost of holding money, and great uncertainty about future inflation will reduce money demand if people are risk averse.

5)

Aren’t these already average inflation rates?

Increases in the expected inflation rate will reduce money demand immediately and raise prices gradually, but the effect on money demand will die out if it’s a one time increase.

For high inflation countries, there may not be much trust that it will be a one time increase though.

If this is just about compounding then, eh, I don’t know.

26. March 2013 at 03:15

Scott:

Assume a balanced budget. Government collect taxes in the form of checkable deposits. The government then spends those funds by writing checks.

Now, the government makes some of its payments with newly-printed currency.

It is still collecting the same taxes, so the government ends up holding a balance in its checkable deposit. This is the tax revenue it didn’t spend. That is, the spending that was instead funded by currency creation.

This represents lending by the government to the banks. The creation of currency, even though there was no budget deficit at all, involves lending by the goverment to the banks.

If the government is running a budget deficit and selling debt to fund some government spending (the normal situation these days,) then when the government makes expenditures with newly created currency to fund some of the expenditures, the natural assumtion is the government sells less debt–borrows less.

26. March 2013 at 05:15

Scott, you should team up with one of these free online universities (like Coursera)and do some monetary theory lectures. You know, in your free time.

26. March 2013 at 05:40

Scott,

I think you have the same problem here that you do in explaining NGDP growth through money issuance. What is the transmission mechanism?

This is actually a hot topic in Japan at the moment among both politicians and business people.

26. March 2013 at 05:58

Dan, Yes, if there were very large terms of trade swings you might want to deviate from strict NGDP targeting. But I do attribute Australia’s success mostly to keeping NGDP growing along a fairly stable trend line, not the commodity boom.

Steve, You are right! Barro’s book has a typo.

Rob, Why would your personal demand to hold cash rise just because the Fed increased the supply of cash? If not, then prices must rise until the real quantity of cash hasn’t changed.

Fed up, I prefer the base, as it is the aggregate actually controlled by the Fed. Changes in the demand for demand deposits matter only to the extent that they impact the base, or whatever the medium of account is.

BTW, what are Cyriot DDs worth? The MOA must have a price that doesn’t change.

Thanks Georges.

Bill, That sounds right.

Justin, That’s what I’m working on.

dtoh, The transmission mechanism is clearly the hot potato effect, as we are looking at the long run, and real asset prices are not affected in the long run. The short run transmission mechanism may differ, as you claim.

26. March 2013 at 06:12

“Rob, Why would your personal demand to hold cash rise just because the Fed increased the supply of cash? If not, then prices must rise until the real quantity of cash hasn’t changed.”

I think I’m trying (apparently not very well) to say something similar to Bill.

The point is that the recipients of the cash are no better off than before as a result of the changed composition of their income so will not increase their spending much. If they don’t want to increase their cash holdings they will just deposit the cash at the bank and the situation will be the same as if they just got a check.

Increased spending will rather be driven by the banks lending out some of the reserves they now have (if the govt simply leaves it in an account at the bank) or by the people who would otherwise be lending money to the govt using that money in other ways (if the govt deficit gets reduced)

26. March 2013 at 06:33

Or by the people who now pay less tax if the govt reduces tax as a result of the new money creation.

26. March 2013 at 08:29

Scott I agree these series of posts are highly informative. However, I second Rob Rawlings question.

I must be missing what he’s missing.

26. March 2013 at 09:46

I agree. If the government sends me $200 in cash or a $200 checkand then collects $200 in taxes, the kind of money I briefly had makes no difference. The bank adjusts it’s cash on hand preferences accordingly and it’s exactly as it was before.

If OTOH the Fed buys a bond it is exchanging a more liquid asset for a less liquid one, and there’s no reflux path unless the Fed decides to start selling.

Now if the Fed prints $200 and puts it in the envelope with my $200 check, that’s different. After I pay my $200 in taxes, that $200 is still somewhere in the private sector providing liquidity.

Of course, the Fed could then sell a $200 bond and sterilize the process, but why should they, given they gave the $200 to me in the first place.

That’s a helicopter drop, and it adds the most monetary services, since I didn’t have to give up some instrument with an inferior but still valuable liquidity premium to get it. And, of course, there’s a wealth effect and a debt paydown (paying off excess debt has a higher utility than acquiring additional wealth, since prevention of disutility = utility) effect in addition. We can argue about how significant they are.

26. March 2013 at 12:23

Dr. Sumner:

“Some Austrians worry about “Cantillon effects,” which means they think it’s important to consider who gets the money first. (Although the term also has other meanings). They assume that that lucky group will boost its spending. Yet the money is not given away, it’s sold at market prices. So the person getting the money first is not significantly better off, and hence has little incentive to buy more real goods and services.”

Sorry, but this is incorrect. The money “sold” is not in fact sold at “market” prices. If it were sold at market prices, then OMOs would have no additional affect on spending or prices in the economy, that an absence of said OMOs would have generated. A clear absurdity.

The error is conflating prices that prevail with a monopoly in money and inflation, and prices that prevail without a monopoly in money and inflation. The latter generates different prices and price levels than the former.

The confusion over whether money is “given away” as opposed to “sold” misses the mark entirely. That is not the right question to ask. The right question to ask is whether prices with inflation from central banks is different from prices without inflation from central banks. The answer to this should be trivial.

Now, as regarding the Cantillon Effect, since we know that inflation from central banks affect spending and prices, the next question to ask is whether or not inflation’s affect on prices are homogeneous or non-homogeneous. The first question’s answer can help here. If we know that inflation from central banks do generate spending and prices different from what would otherwise prevail without inflation or central banks, and we also take into account the fact that primary dealer banks and institutions are the SOLE go-between, the connection, between central banks and the rest of the economy, then if we know that central banks affect spending and prices throughout the economy in ways that are different than what would prevail without inflation from central banks, then it MUST be the case, it HAS to be the case, it is LOGICALLY NECESSARY, that inflation from central banks absolutely without a doubt must generate a different trajectory of spending and prices at the initial inflation injection points, than otherwise would have been the case had the central banks not inflated at all, or inflated at different points in the economy.

In other words, if inflation from central banks does not generate a different trajectory of spending and price at the initial injection points that what would otherwise prevail without inflation, then it is logically necessary that those initial injection points (primary dealers, etc) must not generate a different affect on the spending or selling prices of those they trade with in the secondary markets, and by extension, those secondary markets then cannot bring about a different trajectory of spending and prices of those they trade with in the tertiary markets, and so on down the line, throughout the entire economy. Since we know that is nonsense, since we know that the Fed can bring about different spending and price trajectories throughout the economy, and the central only deals with the primary dealers, then it is necessary that the spending and prices at the initial injection points must be different from what otherwise would have prevailed without inflation.

The primary dealers do NOT buy new dollars at “market” spending values or prices. They buy them at different spending values and prices, so that their trade partners’ spending and price setting is affected, which is necessary for the central bank to affect spending and prices throughout the economy.

In basic logical form:

If C is only dealing with P, and we know that C is bringing about different spending and prices in M, then it must be the case that P is changing spending and prices in M, courtesy of C, and that C must be changing spending and prices at P.

There is no denying this without denying that C affects M. If you deny C affects P, then you are making it impossible for P to affect M, and thus you are making it impossible for C to affect M, an absurdity.

—————

If economic logic doesn’t convince you, then just ask why are the primary dealers interested in being primary dealers? Why are so many banks and institutions desiring to be primary dealers? Why aren’t the existing primary dealers doing whatever they can to get off the primary dealer list? Clearly by virtue of the actions of the individuals in the primary dealer institutions, there is a significant advantage, a gain, to be made by being a primary dealer, or else the individuals involved would not bother.

I recall you once saying that receiving the new money first actually HARMS the initial receiver’s interests. The fact that your reasoning is taking you to a fallacious conclusion, SHOULD be an incentive, an encouragement, for you to seriously rethink your position.

26. March 2013 at 13:05

Geoff:

“Sorry, but this is incorrect. The money “sold” is not in fact sold at “market” prices. If it were sold at market prices, then OMOs would have no additional affect on spending or prices in the economy, that an absence of said OMOs would have generated. A clear absurdity.

”

Hein????

So the primary dealers are getting a discount??? Really??

And then your second statement OMOs have no impact on spending or prices, hein???

The only argument where this would be true is if people had no value whatsoever for money (a cashless society), but even proponents of such theories (such as Michael woodford) acknowledge that this is not the realistic case. Let’s say we are away from the ZLB how do you think the fed is setting the interest rate? A hint using OMO, so clearly OMOs have an impact on prices even if they are done at market prices!! You can argue whatever you want at the ZLB about the efficacy of OMOs but they are clearly done at market price still!

26. March 2013 at 13:32

“so the primary dealers are getting a discount??? Really??”

Yes, in effect, they are. They profit, among other ways, from information asymmetry. All bond dealers do, but primary broker dealers have an edge.

http://dealbreaker.com/2013/01/federal-prosecutors-dont-appreciate-former-jefferies-traders-vivid-imagination/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+dealbreaker+%28Dealbreaker%29

26. March 2013 at 13:48

Georges

“Hein???? So the primary dealers are getting a discount??? Really?? And then your second statement OMOs have no impact on spending or prices, hein???”

No. I didn’t say OMOs have no impact on spending or prices. Dr. Sumner is making that claim.

“The only argument where this would be true is if people had no value whatsoever for money (a cashless society), but even proponents of such theories (such as Michael woodford) acknowledge that this is not the realistic case. Let’s say we are away from the ZLB how do you think the fed is setting the interest rate? A hint using OMO, so clearly OMOs have an impact on prices even if they are done at market prices!! You can argue whatever you want at the ZLB about the efficacy of OMOs but they are clearly done at market price still!””

To the extent this passage assumes I believe OMOs have no affect on spending or prices (specifically the spending and prices concerning that which the primary dealers buy), it is not related to what I said. I am trying to see how it would relate even if it doesn’t make that assumption, but I am at a loss…

26. March 2013 at 14:32

Geoff, yes this passage assumes that indeed. If I read back your message you are saying that if OMOs were done not at market price then they would have no impact on prices and spending, right?

It’s this assumption that I’m contesting.

Peter N, what are you trying to say with this article? That there are bond traders committing frauds? You bet there are! But I don’t see how can this be related to how monetary policy is done, and I would hardly be convinced that OMOs are only working if there is a fraud involved!

Primary dealers are getting commissions from those transactions no doubt, but this is tiny compared to the size of those operations and is certainly not the reason why OMOs impact prices.

26. March 2013 at 14:42

Geoff, what prof sumner is saying is that OMOs are not increasing the wealth of the people (which is certainly true at least on aggregate) and so is not changing the propensity to spend of the people, but it’s increasing the monetary base which would then have inflationary impact which would make people spend more.

26. March 2013 at 14:42

Geoff, what prof sumner is saying is that OMOs are not increasing the wealth of the people (which is certainly true at least on aggregate) and so is not changing the propensity to spend of the people, but it’s increasing the monetary base which would then have inflationary impact which would make people spend more.

26. March 2013 at 14:43

Geoff, what prof sumner is saying is that OMOs are not increasing the wealth of the people (which is certainly true at least on aggregate) and so is not changing the propensity to spend of the people, but it’s increasing the monetary base which would then have inflationary impact which would make people spend more.

26. March 2013 at 14:43

Geoff, what prof sumner is saying is that OMOs are not increasing the wealth of the people (which is certainly true at least on aggregate) and so is not changing the propensity to spend of the people, but it’s increasing the monetary base which would then have inflationary impact which would make people spend more.

26. March 2013 at 14:43

Geoff, what prof sumner is saying is that OMOs are not increasing the wealth of the people (which is certainly true at least on aggregate) and so is not changing the propensity to spend of the people, but it’s increasing the monetary base which would then have inflationary impact which would make people spend more.

26. March 2013 at 14:46

Sorry for the spam, not sure what happened here it posted 5 times …

26. March 2013 at 14:59

Georges:

“Geoff, yes this passage assumes that indeed. If I read back your message you are saying that if OMOs were done not at market price then they would have no impact on prices and spending, right?”

No, you still don’t have it. I am saying that if OMOs were done not at market prices and spending (i.e., meaning at non-market market prices and spending), then they would have an impact on what would otherwise be market prices and spending.

In other words, if OMOs are done at market prices and spending, then they would not have any affect on spending and prices over time throughout the economy. The fact that OMOs do affect prices and spending throughout the economy, means that it is necessary that for the only institutions the central bank does deal with, the primary dealers, the prices and spending at this initial stage MUST be affected. If it isn’t affected, the primary dealers could not affect the spending and prices regarding the exchanges they make with others not the central bank.

“Geoff, what prof sumner is saying is that OMOs are not increasing the wealth of the people (which is certainly true at least on aggregate) and so is not changing the propensity to spend of the people, but it’s increasing the monetary base which would then have inflationary impact which would make people spend more.”

I am not saying inflation increases real wealth in the aggregate either. I am saying it increases relative spending and prices for the primary dealers, which is necessary in order for the primary dealers to then increase the spending and prices throughout the rest of the economy. This is because the spending and prices in the rest of the economy, in the aggregate, must be affected by the primary dealers if we are going to argue that central banks affect prices and spending throughout the economy. The central bank only deals with the primary dealers, so if the rest of the economy is affected, the primary dealers must be affected, and by affected I mean different from what would otherwise have prevailed without the inflation from the central bank.

It is contradictory to hold both of these positions at the same time:

1. Central bank inflation affects prices and spending throughout the economy.

2. Spending and prices at the primary dealer stage are not affected by central bank inflation.

PS You posted 5 times because you clicked submit 5 times because you thought it didn’t submit properly, due to temporary delays, glitches, etc, in the server.

26. March 2013 at 15:29

Geoff,

Yes I think I got your point and I don’t agree with it. What you are saying is that the fed is buying the bond from the primary dealer with the primary dealer benefiting from this transaction. This will change the market prices of bonds to reflect this transaction (I find that plausible but this would benefit all bond holders in the economy and not just the primary dealers).

What you are saying is that inflation will necessarily go from one person to the next and cannot kind of propagate to the whole population. I’m saying it can.

First of all the biggest beneficiaries of this are bond holders and not primary dealers (they are not necessarily bond holders), second OMOs could have impact on people’s expectation (indeed I argue that in the ZLB it’s almost the only impact it has). Third it could have an impact on the interest rates lowering them down so everyone will be impacted by this.

If OMOs are very efficient then bond prices will instantly drop and indeed bond holders will gain from this but not necessarily primary dealers, it’s not who receive the money that benefits but it’s the holders of the asset that is gaining in value who is gaining. And you also have the expectation effect which would have a more homogeneous impact.

26. March 2013 at 15:53

Georges:

“Yes I think I got your point and I don’t agree with it.”

You keep disagreeing with contradictory, mutually exclusive “points” that you thought I was making.

I think you’re just disagreeing for the sake of disagreeing. Why else would you disagree with two exhaustive claims, one after another, despite the fact that you are logically obligated to agree with at least one of them?

“What you are saying is that the fed is buying the bond from the primary dealer with the primary dealer benefiting from this transaction.”

If the primary dealer did not benefit from the transaction, then the primary dealer would not engage in the transaction. The fact that they do engage in the transaction suggests they are indeed benefiting.

Moreover, you’re somewhat missing the mark here. Put aside “who benefits” for a second and ask yourself if it is possible for the central bank to affect spending and prices throughout the economy while not affecting the spending and prices of the only institutions it deals with, the primary dealers.

“This will change the market prices of bonds to reflect this transaction (I find that plausible but this would benefit all bond holders in the economy and not just the primary dealers).”

It is not actually relevant to this issue whether or not the security types the central bank buys goes up or down as a class, which would seem to suggest that every holder of said security type gains or loses together.

For one thing, not everyone can be a speculating bond seller. There must be buyers, that is, there must be those who do not own those bonds but stand to buy those bonds at higher or lower prices. It is a mistake to believe that because prices of bonds the central bank does not specifically buy change due to OMOs, that everyone can in principle take advantage of the gains if they exist, or avoid the losses if they exist.

If everyone bought bonds hoping to sell them at, say, higher prices, then the prices would collapse to zero, since the demand for bonds would be zero as everyone is intending to sell.

But this is besides the main issue here. The issue is whether or not inflation affects the spending and prices at the primary dealer stage, compared to what it otherwise would have been without the inflation.

Dr. Sumner is arguing that the primary dealers are paying “market prices” for money and bonds. My argument is counter-point to that position. My argument is that it is wrong. I explained why I think it is wrong, and so far you have not addressed this, but rather detoured to other, tangential points that don’t directly address the issue.

“What you are saying is that inflation will necessarily go from one person to the next and cannot kind of propagate to the whole population. I’m saying it can.”

Well then you’re wrong about that too. If the central bank doesn’t send everyone checks, then inflation necessarily is a “propagating” phenomena.

“First of all the biggest beneficiaries of this are bond holders and not primary dealers (they are not necessarily bond holders)”

I am not making a case as to who are the “biggest” beneficiaries. I am solely addressing whether or not spending and prices are affected at the primary dealer stage, due to OMOs.

“second OMOs could have impact on people’s expectation (indeed I argue that in the ZLB it’s almost the only impact it has).”

Everyone cannot have the same expectations, and everyone cannot act on the same expectations.

“Third it could have an impact on the interest rates lowering them down so everyone will be impacted by this.”

If rates decline, then, ceteris paribus, there must be an abstaining from spending on things other than bonds, to make available the funds with which to buy bonds at the higher prices.

If this happens, then those who sell bonds are benefited at the expense of those who buy bonds at the higher prices.

“If OMOs are very efficient then bond prices will instantly drop and indeed bond holders will gain from this but not necessarily primary dealers, it’s not who receive the money that benefits but it’s the holders of the asset that is gaining in value who is gaining.”

Nothing in human life is instantaneous.

“And you also have the expectation effect which would have a more homogeneous impact.”

Not everyone has the same expectations, nor can they have the same expectations for exchanges to take place. In order for exchanges to take place, there has to be differences in opinions on value.

26. March 2013 at 16:11

Primary broker dealers have more price information available to them, so they can earn superior spreads. With no posted prices, the market isn’t efficient. The money involved isn’t trivial, because the volume is huge. Whether this information asymmetric rent has any macro effect, I couldn’t say.

However I think the banking sector as a whole has an extremely bad effect. Their share of the economy has reached a point not seen since 1932.

26. March 2013 at 16:20

Geoff, let me start with a few questions this way we can understand each other:

1) OMOs cause inflation?

2) if answer to 1 was yes, is it inflation caused from the primary dealers being wealthier and therefore spilling over?

My answers are 1) yes 2) no

The dealers are getting a commission on their sell and will benefit from the general NGDP growth but this is it, there is no domino effect.

As for the interest rate story, this is not a zero sum game, if ir goes down, loans are cheaper and people will therefore spend and invest more boosting AD, it’s not a pure substitution effect.

Rates are at 10%, you will not get a loan and buy this new car you had in mind, now rates are at 0.5% you will take a loan and buy it, I don’t see how can this crowd something else out? You can argue that if you take a loan someone must be borrowing you, yes the government/central bank would be.

Most people by expecting the fed will keep the rates down for 10Y will take out more loans which will increase AD and generate higher NGDP, you don’t actually even need to do anything, we have seen the market reacting to just the fed announcing some program, this is forward guidance.

You can see how the stock market reacts almost instantaneously to the Fred’s announcements. You don’t even need OMOs for that matter (although OMOs sure help a lot with the convincing bit and with flooding the market with new loans)

26. March 2013 at 18:45

Georges:

If you accept that the central bank’s inflation results in a change to aggregate spending and prices, and if you accept that the central bank makes exchanges with only the primary dealers, then you are logically obligated to hold that the central bank affects the spending and prices of primary dealers, for if it didn’t, then it could not affect aggregate spending and prices.

You cannot hold that the central bank causes aggregate inflation, without also holding that the central bank affects the prices of exchanges with the primary dealers. If you deny the latter, then you must deny the former.

As regards to your opinions on interest rates, they have no bearing on the issue.

The error you are making is that you are completely evading the necessary middle step between central bank activity, and the subsequent affect on aggregate spending and prices. There is indeed a “spill-over” effect. To deny this is to display a misunderstanding of the nature of inflation.

26. March 2013 at 19:28

Rob, You said;

“If they don’t want to increase their cash holdings they will just deposit the cash at the bank and the situation will be the same as if they just got a check.”

Sorry, that won’t work either, as the bank won’t want to hold cash that earns no interest.

Mike and Peter, See my answer to Rob. You don’t want to think about what makes people want to spend more, but rather the fact that people want to get rid of money they don’t want, but they cannot do so (collectively.) Inflation is not fundamentally about prices rising, that’s a side effect. It’s about cash losing value because the Fed has printed more cash than people want to hold.

Geoff, You are wrong, I suggest taking a look at my earlier posts on the Cantillon effect.

Georges, Don’t worry, it was worth repeating 5 times. 🙂

26. March 2013 at 19:49

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, You are wrong, I suggest taking a look at my earlier posts on the Cantillon effect.”

No, you are wrong, and I showed why you are wrong in those earlier posts.

“Georges, Don’t worry, it was worth repeating 5 times.”

Georges’ post did not address the issue raised.

26. March 2013 at 21:13

“Sorry, that won’t work either, as the bank won’t want to hold cash that earns no interest.”

Right, so the bank will send its excess cash to the Federal Reserve where it will be credited to its reserve account. Problem solved, the cash has left the system. It’s back where it started, at the Fed.

That’s what we don’t get. Why doesn’t the bank just send the excess cash back to the Fed in exchange for reserves?

26. March 2013 at 22:12

Scott,

I hate to keep on harping on this, but to achieve a more general understanding and acceptance of the theory, you need to delve more into the transmission mechanism. If you look at the objections raised by politicians, economists, and journalists it all relates back to a failure to understand the transmission mechanism.

Just to give you an example, please explain how OMP in your model does not result in all inflation and no real growth, or alternatively explain why OMP doesn’t result in no inflation and all real growth, or explain why at the ZLB OMP doesn’t just result in a decrease in V.

26. March 2013 at 22:41

The concept of a unique quantity of money for a given price level only applies if seignorage (on *both* reserves and currency) is positive. This hasn’t been the case since 2008.

Note that the Fed could make seignorage on reserves positive by lowering interest on reserves, but then seignorage on currency would turn negative.

26. March 2013 at 23:09

Geoff, my point on interest rate was a response to your post on the rates declining bit.

I don’t see how it’s contradictory to say that inflation is happening in the economy not through a spillover effect, I gave you one mechanism where this could happen (expectations).

Another mechanism, bonds are trading at 100, fed announces I want to buy bonds at 110, instantaneously all bonds and close substitutes to bonds will drop in price, this is a generalised inflation caused by not a spillover effect but a mere declaration (Bond traders will only earn commission on this and that’s it which is just a few bps).

I guess let’s agree to disagree, or as prof sumner has suggested check the cantillon effect post, but please explain one fact: how is the stock market reacting instantaneously to the Fed’s announcements (and I’m saying announcements not even actions) if inflation has to propagate through spillover effect?

27. March 2013 at 03:57

Georges:

“Geoff, my point on interest rate was a response to your post on the rates declining bit.”

I didn’t say anything about rates declining over time. My position on interest rates is that there are at least two nominal forces acting on interest rates, one that raises rates, and one that decreases rates. The nominal force that raises rates is indirectly through price inflation and the resulting inflation premiums. The nominal force that decreases rates is directly through increasing the supply of credit and the resulting “liquidity effect” negative premium.

Which one of these two forces dominates the other is an empirical question, but both are always present. The nominal force that decreases interest rates, even if price inflation is putting an increasing pressure on interest rates such that it dominates, is still making interest rates lower than they otherwise would have been had the inflation entered the economy directly in the purchase of final goods.

This is the counter-factual that relates to the spending and prices that are different with inflation than without inflation, if the initial inflation is exchanged for bonds that we traditionally model by including only one nominal force, namely the inflation premium one, that leads to such statements as “Inflation results in higher interest rates, what are you talking about?”

Your response is also not addressing my actual point about whether the spending and market prices are different from what they otherwise would have been had the inflation not taken place.

“I don’t see how it’s contradictory to say that inflation is happening in the economy not through a spillover effect, I gave you one mechanism where this could happen (expectations).”

That’s unfortunate. To restate it, it’s contradictory because the primary dealers are the sole conduit by which the central bank affects aggregate spending and prices. If the spending and prices at the primary dealer level are no different with the OMOs, then it follows that aggregate spending and prices in the economy will be no different.

Expectations cannot raise aggregate spending and prices year after year after year. Expectations without an actual corresponding “spill-over” from the inflation, would result in aggregate spending and prices to top out. This follows from the QTM, which holds that the amount of spending that exists in the economy is ultimately a function of how much money actually exists in the economy.

“Another mechanism, bonds are trading at 100, fed announces I want to buy bonds at 110, instantaneously all bonds and close substitutes to bonds will drop in price, this is a generalised inflation caused by not a spillover effect but a mere declaration (Bond traders will only earn commission on this and that’s it which is just a few bps).”

This is not a general increase in prices that is a necessary component to the argument being considered. What you are describing here is a rise in spending on bonds which comes at the expense of a decreased spending for other goods/securities. If there is no inflation of the money supply, then spending more on X means there is less to spend on everything else. General prices and general spending do not rise in this way.

Only if the central bank actually increases the supply of money, can any increased spending on bonds NOT be accompanied by a decreased spending on everything else, such that general spending and general prices rise over time.

You are placing far too much emphasis on expectations. This is problematic, on multiple levels. One, it is leading you to suppose that price adjustments are instantaneous, which is impossible, two, it is leading you to believe that something only inflation of the money supply can do, can be done by mere words, and three, it is leading you to ignore the real world “spill-over” effect that no amount of expectations and preparation can avoid.

“I guess let’s agree to disagree, or as prof sumner has suggested check the cantillon effect post”

I’ve shown how Dr. Sumner is wrong in that post. Why are you blindly repeating his recommendation, when you clearly don’t have all the facts to make such a statement?

“but please explain one fact: how is the stock market reacting instantaneously to the Fed’s announcements (and I’m saying announcements not even actions) if inflation has to propagate through spillover effect?”

The stock market is not reacting instantaneously to Fed announcements. Your assumption is wrong.

Not only does it react with a time lag, but the full effects of an inflation are not immediately priced into stocks. The rise in prices of stocks we see today are the result of past inflation as well as recent inflation, as more and more people whose incomes have finally risen during the “spill over effect” transition, are able to put forth a higher nominal demand for stocks and increase stock prices further. Prices are a function of supply and demand.

Inflation of the money supply does not all instantly translate into nominal demand for stocks. Stock prices rise as the inflation spreads throughout the economy, raising the nominal incomes of individuals (in a process better described as) “one by one”, and as those individuals save and invest that new money, then stock prices will go up further (if they went up initially).

There is no way to arbitrage this by you paying higher stock prices initially, because you can’t scientifically predict just how much of the new money from subsequently higher incomes will indeed go to stock price demand.

MM theory is fundamentally flawed in its denial of “long and variable lags.”

27. March 2013 at 03:59

Also, these positions cannot co-exist:

1. Prices instantly adjust to changes in monetary inflation.

2. Unemployment is generated by changes in monetary inflation.

27. March 2013 at 05:47

“Sorry, that won’t work either, as the bank won’t want to hold cash that earns no interest.’

So I think you are saying: I take the cash I don’t want to hold to the bank and they use it as reserves to lend out and this will increase spending and the price level

But I am still missing it:

before:

I get a check for $1000 and I spend it all by writing checks

after:

I get a check for $800 and $200 in newly printed bills. I spend it all by writing checks and spending cash or I take the cash to the bank and write checks just like before.

I don’t see any real difference between before and after as far as either I or the bank is concerned. I still think the beneficiaries of this new money are the people who are paying me my $1000 as $200 now gets newly created and they can spend $200 on something else.

27. March 2013 at 06:32

Peter, You said;

“Right, so the bank will send its excess cash to the Federal Reserve where it will be credited to its reserve account. Problem solved, the cash has left the system. It’s back where it started, at the Fed.”

That won’t work either, as the banks don’t want to hold non-interest-bearing reserves at the Fed, when they can hold interest bearing T-bills.

dtoh, I’ll do that in later posts.

Max, How can seignorage on currency be negative?

Rob, You are right that your behavior is initially no different–that was my point about the non-importance of Cantillon affects. You are not richer, and hence don’t buy more goods (initially). But total NGDP begins to rise due to the hot potato effect. Your behavior changes in one respect–you try to get rid of excess cash balances. As an individual you can do so, but collectively society cannot do so. Think in terms of the fallacy of composition, that’s the concept that underlies all of monetary economics. Everything else is just a footnote.

You are thinking in Keynesian terms, and you CANNOT understand monetary economics while thinking in Keynesian terms. It’s not about spending on real goods and services, it’s about the supply and demand for the monetary base. When the supply goes up, the base loses value, for the same reason that more apples being harvested make apples lose value. Othe things cost more in apple terms, but not because the “aggregate demand for real goods in apple terms” went up. It was because apples were worth less.

27. March 2013 at 07:15

Scott,

Surely whenever new money is created someone has to get it and spend it for it to have any effect?

In the case of OMOs the new money is spent by the fed on assets that it hold hold to implement monetary policy so the effects are more-or-less neutral in its distributional effects.

In your example the new money is spent by the govt agency that issue the checks (not by the recipients). If they don’t increase spending as a result of the new money but just hold bigger balances then I still contend that the monetary base will increase, but velocity will fall (as a result of the agencies larger balances) and the price level won’t change.

27. March 2013 at 07:17

By “If they don’t increase spending” I mean the agency that issues the checks that is the beneficiary of the new money.

27. March 2013 at 08:06

“That won’t work either, as the banks don’t want to hold non-interest-bearing reserves at the Fed, when they can hold interest bearing T-bills.”

The two forms of base money are interchangeable. It doesn’t matter which form the government sends me.

I think your hypothetical intent was:

Suppose instead of sending ma check for $1000 from the treasury, the check is for $800, and the Fed supplies the last $200 with money from it’s own balance sheet, not the treasury’s account.

Now you’ve increased the monetary base by $200. However, it doesn’t matter what form of money is sent, if it comes from the treasury’s account, because forms of base money are fungible, and banks can invest excess reserves in t-bills it they want.

Interest on reserves gives banks an alternative to T-bills. Otherwise there would be a shortage of T-bills, and money market funds would have a problem staying solvent.

I’m using this reference:

http://synthenomics.blogspot.com/2012/08/interest-on-excess-reserves-illustrated.html

which itself draws on Dave Beckworth and Cardiff Garcia

BTW this is a response to your post on Chinese housing from the same source

http://synthenomics.blogspot.com/2012/09/chinese-housing-reply.html

I pretty much agree with everything he says on the subject.

27. March 2013 at 08:15

Geoff,

your statement is quite strong:

“I’ve shown how Dr. Sumner is wrong in that post”

We must not have the same definition of proof ….

“The stock market is not reacting instantaneously to Fed announcements. Your assumption is wrong.”

hein? Are you checking the stock market prices? Read Woodford’s Jackson hole paper on this, it should be an eye opener.

Anyway, I feel there is no way we will advance on that front, clearly you do not want to accept a different interpretations of the facts besides your own, maybe I’m wrong but you have clearly not shown that at all!

27. March 2013 at 08:19

Scott,

I’ve a question which is related to Rob Rawlings’. Imagine an economy with a fixed pool of investment goods. People can only produce consumption goods. Nevertheless, people want to save more (which is impossible since there are no more investment goods), so they hoard the medium of exchange misusing its “store of value”-property and create a fall in AD.

What do you do now? Open market operations, printing money and buying some of the fixed pool of investment goods, won’t work, because for every investment good people lose, they will hoard money as a substitute. Each open market operations will raise the demand for money by reducing the supply of investment goods.

Isn’t it right to say that in this case only helicopter drops can work, not open market operations?

27. March 2013 at 08:25

Georges:

“Geoff, your statement is quite strong:”

“I’ve shown how Dr. Sumner is wrong in that post”

It was no more strong than Dr. Sumner’s statement that I am wrong.

“We must not have the same definition of proof ….”

You don’t know my definition.

“The stock market is not reacting instantaneously to Fed announcements. Your assumption is wrong.”

“hein? Are you checking the stock market prices? Read Woodford’s Jackson hole paper on this, it should be an eye opener.”

Yes, I am checking stock market prices. Yes, I have read that paper. I still hold that stock prices do not instantly adjust to inflation.

“Anyway, I feel there is no way we will advance on that front, clearly you do not want to accept a different interpretations of the facts besides your own, maybe I’m wrong but you have clearly not shown that at all!”

I have shown how you are wrong about inflation and whether or not it changes spending and prices at the primary dealer stage. I haven’t shown how you are wrong in the other areas, because I only have two hands.

27. March 2013 at 08:30

Georges:

For the stock price adjustment issue, if you accept that today’s saving and nominal demand for stocks, by you and me and everyone else who earns an income, can affect stock prices today, and if you accept that your income does not instantly rise when Bernanke inflates, but rather than time must pass before such inflation percolates throughout the economy, such that a few months or a year must elapse before you get a raise from past inflation, it follows that you must hold the position that stock prices do not instantly adjust from initial inflation, but are affected over a time period that spans however long it takes for your income to rise due to Bernanke’s inflation into the banking system.

There are so many people on this blog who are so confused about how inflation works. It’s like there is this widespread denial that inflation affects spending and prices non-homogeneously, that everyone’s incomes are raised at exactly the same rate and at the exact same time, when Bernanke increases the supply of bank reserves.

27. March 2013 at 08:45

Geoff, there have been a lot of work in inflation mechanism and very few fit your narrow criteria.

What you are talking about stock prices is not correct, if you believe in EMH you would know that what you are saying is wrong, but you don’t even need to believe in EMH, it’s enough to just believe in a very weak EMH version, or in Rational Expectations to see that what you are saying is not exact.

27. March 2013 at 08:56

“You are thinking in Keynesian terms, and you CANNOT understand monetary economics while thinking in Keynesian terms. It’s not about spending on real goods and services, it’s about the supply and demand for the monetary base”

I think this is an unfair statement. In all my comments I have been trying to make the same point – that your example lacks all the relevant information needed to see how the change you describe to the monetary base will affect the supply and demand for it – leaving the impression that just changing the composition of someone’s income between cash and check will somehow kick off a hot potato effect.

I don’t see how this can be described as “Keynesian thinking”

27. March 2013 at 09:19

Georges:

“Geoff, there have been a lot of work in inflation mechanism and very few fit your narrow criteria.”

There has been a lot of work on the mechanism that fits my criteria, and regardless of the relative size of this work, it has no bearing on the quality or truth of it. In 1900, relativistic physics research was far outweighed by Newtonian physics research. But that didn’t mean relativistic physics was less right.

You’re teetering very close to ad populum fallacy.

“What you are talking about stock prices is not correct, if you believe in EMH you would know that what you are saying is wrong, but you don’t even need to believe in EMH, it’s enough to just believe in a very weak EMH version, or in Rational Expectations to see that what you are saying is not exact.”

EMH is one theory among many that are consistent with historical data.

I don’t personally adhere to it, because it suffers from numerous internal logic problems.

Rational expectations is definitely false, because it presumes that every individual has the same knowledge set, and the same expectations set. In the real world, there are disagreements.

What you are saying is not correct if you accept a real world, economically sound theory.

27. March 2013 at 10:09

Geoff, and what would that real world economically sound theory? yours presumably? 🙂

You don’t see how you are going in circles, I’m right hence I’m right. You discard theories off hand because they don’t fit your criteria, and you say if someone does not agree with you then they have not understood the inflation mechanism.

I’m not saying that what I’m saying or what ssumner is saying is the absolute truth, but I have given you different mechanism where what I’m saying can be true, and you just discard them off hand because they don’t fit your definition of how things work!

27. March 2013 at 10:34

Georges:

“Geoff, and what would that real world economically sound theory? yours presumably?”

Anyone can learn it and accept it. It isn’t “mine.”

“You don’t see how you are going in circles, I’m right hence I’m right.”

I am not making that argument, nor implying it. Can you be more specific?

“You discard theories off hand because they don’t fit your criteria”

I discard theories when I notice internal flaws in them.

“and you say if someone does not agree with you then they have not understood the inflation mechanism.”

It’s not just about disagreement. It’s about the erroneous positive claims I see you making.

“I’m not saying that what I’m saying or what ssumner is saying is the absolute truth, but I have given you different mechanism where what I’m saying can be true, and you just discard them off hand because they don’t fit your definition of how things work!”

It’s not “off hand”. Did you actually believe that your claims are the first time I have ever heard them? I’ve seen them and studied them in detail.

Perhaps you have accepted your theories without much thought, and so you believe that they can only be discarded the same way? I know you didn’t think of them yourself. You were taught them and you accepted them on the basis of trusting what you perceive to be authorities and your superiors. I question authority, and I have no qualms with rejecting and accepting theories from authorities based on my own accumulated knowledge.

You still haven’t responded to my challenges. You haven’t even engaged them or recognized them as being challenges.