Money and Inflation, part 5: It’s (almost) all about expectations

This is the final money and inflation post. Then I’ll do one post on money and business cycles, and conclude the mini-course with a post on money and asset prices (including interest rates.) Nine posts in all.

In the previous post we saw that increases in the rate of money growth lead to higher inflation, which leads to higher velocity and lower real money demand. This means that in the long run an increase in the money supply growth rate will cause prices to rise by even more than the money supply increased. Conversely if money growth slows, inflation will slow, the opportunity cost of holding base money will fall, money demand will rise, and prices will rise by less than the increase in the money supply. That’s one way that expectations play a role in the money inflation equation.

The more interesting examples occur when there is a change in the expected future level of the monetary base, but no current change in the base. Consider the following two examples:

1. A new government is elected and is expected to print lots of money (perhaps to juice the economy.) Prices will rise in anticipation of that increase in the money supply. A good example occurred between March 1933 and February 1934, when the Wholesale Price Index rose by over 20%, despite no increase in the monetary base. The public anticipated (correctly) that the devaluation of the dollar would lead to a higher money supply in future years. That increased current base velocity, reduced real money demand, and increased prices almost immediately.

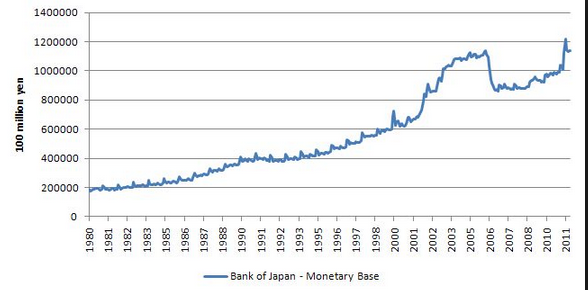

2. The opposite situation occurs when a government injects large quantities of money into the economy, but tells the public that it will be removed as soon as there is any sign of inflation. In that case the interest rate will fall to zero, and the public will willingly hold much larger real cash balances. This occurred in Japan between the early 2000s, when lots of base money was injected, and 2006, when the monetary base was reduced by 20% in order to prevent inflation from occurring.

(It’s not clear the extent to which the recent low inflation in the US reflects this factor, and how much reflects the 2008 decision to pay interest on reserves.)

So the current path of inflation is very heavily influenced by expectations. But expectations must be about something, and in this case they are about future changes in the monetary base (and future changes in the demand for base money.) If we ignore expectations, then we can say the “hot potato effect” drives the long run relationship between changes in the money supply and changes in the price level. Once we bring expectations into the picture, then it’s the expected future hot potato effect that mostly explains current inflation.

Unfortunately the role of expectations makes monetary economics much more complex, potentially introducing an “indeterminacy problem,” or what might better be called “solution multiplicity.” A number of different future paths for the money supply can be associated with any given price level. Alternatively, there are many different price levels (including infinity) that are consistent with any current money supply. Thus if the public believes money will be declared null and void next week, it may have no value today (think Confederate money toward the end of the Civil War.) So lurking in the background there must be some sort of confidence that money will have purchasing power in the future. There is much debate over what sort of implied promise is embedded in money. My best guess is that the public (correctly) believes that if and when currency is replaced by electronic money, the government will redeem the currency they pull out of circulation for some sort of alternative asset with roughly the same purchasing power.

The next step is to explain why monetary policy does not just affect prices, but also has real effects. It turns out that this is pretty easy to do, and I’ll cover that in the next post.

Tags:

1. April 2013 at 13:49

1. “A new government is elected and is expected to print lots of money (perhaps to juice the economy.) Prices will rise in anticipation of that increase in the money supply.”

Does Joe Sixpack know and understand what Bernanke did yesterday, and how his (Bernanke’s) activity will affect Joe’s income and the prices of goods he buys in the future? If not, inflation is not “almost all” about expectations, but rather “some of it is”. Most people who engage in the division of labor, who affect prices through market supply and demand, are Joe Sixpacks when it comes to how inflation will affect their incomes and the prices they pay. Just consider how clueless Ivy League PhD economists working at central banks around the world are, to get a sense of this.

2. “A good example occurred between March 1933 and February 1934, when the Wholesale Price Index rose by over 20%…That increased current base velocity, reduced real money demand, and increased prices almost immediately.”

Wasn’t the one year period of rising WPI, an example of prices not rising immediately, but over time, given innovating individual expectations of future inflation? For many people, they need to SEE higher prices before they agree that a higher price is justified. It’s not like every individual in the market knows exactly how current monetary inflation will affect future prices and incomes, such that they go out and raise prices and incomes now, such that past inflation becomes fully “priced in.” We don’t see vertical step ladder price trends. We see sloping price trends.

3. “If we ignore expectations, then we can say the “hot potato effect” drives the long run relationship between changes in the money supply and change sin the price level.”

In the long run, the hot potato effect is the ONLY driver of of the relationship between changes in the money supply and changes in the price level. Expectations of future inflation cannot make price levels rise to arbitrary levels in the present. Price levels in the present are constrained by the money supply itself in the present. There is no way that the price level could be what it is now, back in 1920 say, with the 1920 money supply. Today’s price level requires today’s much greater money supply.

Even if you told me that inflation is going to be twice what it is now, next year, I still won’t be able to spend twice as much. I need to make twice the income. It becomes even more obvious with longer term inflations, with three, four, five times the nominal income growth.

1. April 2013 at 14:01

“Even if you told me that inflation is going to be twice what it is now, next year, I still won’t be able to spend twice as much. I need to make twice the income.”

Or… have banks loosen credit standards and lend you the money. But I agree, next year is far off. Next month…

“It becomes even more obvious with longer term inflations, with three, four, five times the nominal income growth.”

At this point one is already f****d.. There’s simply too much inflation in the economy. Unlike the one-size fits all misean-rothbardian nut jobs, we don’t ALWAYS think one thing is the answer. In that situation, the central bank needs to do a VOLCKER, and fast.

By the way, in a fiat money economy, The Fed can use the interest it pays on reserves to control inflation. Printing money and then using that to pay people to hoard their cash in one place not only doesn’t cause inflation, it decreases it dramatically

1. April 2013 at 14:22

“a government injects large quantities of money into the economy, but tells the public that it will be removed as soon as there is any sign of inflation.”

But the government must have assets of some kind in order to buy back that money. If the government has no assets, the public knows there will be no buy-back, and so government-issued money will have no value.

If paper dollars are valued because of expected future buy-backs, and if buy-backs are only possible when the money-issuer has assets, then it follows that the value of paper dollars depends on the issuer’s assets.

1. April 2013 at 15:37

If the shape of the yield curve is an accurate representation of current expectations of future inflation, then a steep yield curve suggests that inflation is expected to increase. And people will spend more money today if inflation is expected to increase in 6 months.

There are many out there who suggest that low intermediate-term rates are more stimultative than low short-term rates. I know, the rates themselves are not an indication of the stance of current policy….

But if steep curve is stimulative, Operation Twist was misguided.

1. April 2013 at 16:50

Geoff, I meant that prices will rise somewhat almost immediately, You are right that the full effects take some time to play out.

Edward, Yes, IOR can affect inflation, I was assuming no IOR.

Mike, But what if they double the money supply, AND have the assets to back it up, and announce it will be permanent. I say prices double. What say you?

Doug, I also have doubts about Operation twist, but at the zero bound there is debate over whether the yield curve has the same predicative ability, as it is now constrained and doesn’t accurately reflect credit market conditions. The equilibrium nominal rate might be negative at the short end.

1. April 2013 at 17:50

The most fascinating aspect of the current situation is that the Fed’s long-term target is so credible that they can buy trillions in assets without creating much inflation.

When you stand on the brake, you can push the gas pretty hard without going much of anywhere.

2. April 2013 at 00:11

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, I meant that prices will rise somewhat almost immediately, You are right that the full effects take some time to play out.”

What would the historical price data have to look like if prices did not rise somewhat almost immediately, but rather rose over a somewhat longer length of time, say in the weeks and months lengths of time?

Also, what “full effects” are you referring to, if not prices?

2. April 2013 at 01:33

Mr Sumner,

can exchange rate be an indicator of the movement in the base for the general public (i am aware that monetary base is not only determinant of exchange rate), but bear with me here)? In Yugoslavia, as well as in Croatia today, people pay a lot of attention to exchange rate since Yugoslavia was continually devaluing by printing more dinars (i think 14 decimal places were “removed” by 1993). So people saw inflation – devaluation and had their savings in DEM and housing. Im writing this to ask how you see a change in policy from stable exchange rate to some floating regime could affect short term inflation and long term inflation expectations? As Geoff wrote in his first post “Does Joe Sixpack know and understand what Bernanke did yesterday, and how his (Bernanke’s) activity will affect Joe’s income and the prices of goods he buys in the future?” – could this be a situation where Joe actually uses an indicator to asses MP stance even though he may not know much about underlying changes?

2. April 2013 at 02:06

“Mike, But what if they double the money supply, AND have the assets to back it up, and announce it will be permanent. I say prices double. What say you?”

I’ve never been able to figure out what you mean by permanent. As far as I know any permanent money supply or interest rate target would leave the price level undefined.

The central bank’s assets don’t define the price level either, but they constrain it. The constraint is that the CB has to be solvent. If the CB isn’t solvent, the price level rises until it is. This limits the ability of the CB to lower the price level, but places no limit on the ability to raise it.

The ‘fiat’ in fiat money is that the price level is whatever the CB says it is, subject to the solvency constraint.

In the gold standard days, the CB raised the price level by increasing the price of gold. The analogous action for a CB today is to announce a price index target.

2. April 2013 at 02:51

Scott,

You said;

“The next step is to explain why monetary policy does not just affect prices, but also has real effects. It turns out that this is pretty easy to do, and I’ll cover that in the next post.”

Hopefully, you’ll provide a model/ mechanism by which one can accurately breakdown how a change in M will translate into a change in prices versus a change in real output.

2. April 2013 at 03:47

“The next step is to explain why monetary policy does not just affect prices, but also has real effects. It turns out that this is pretty easy to do, and I’ll cover that in the next post.”

I wonder if the “real effects” that are going to be discussed, will include relative, micro-level effects, and not just aggregated, macro-level effects.

2. April 2013 at 04:19

TallDave, Good point.

Geoff, Commodity prices rise almost immediately, consumer goods and service prices rise more gradually.

Petar, Yes, average people may look at exchange rates, but also other indicators like stock prices. As I argued earlier, I wouldn’t fixate too much on inflation, which is a variable that doesn’t really matter in macro–NGDP growth expectations are more important.

Max, No, the price level is not whatever the central bank says it is, it’s determined by the interaction of money supply and money demand. The Fed didn’t suddenly decide to cut the price level in 2009. But it fell anyway.

dtoh, Too late, I’ve already written the last two posts in the series. But I look forward to your suggestions.

Geoff, Yes, I’ll talk about nominal hourly wages relative to NGDP.

2. April 2013 at 04:33

“Too late, I’ve already written the last two posts in the series.”

Never too late to rewrite!!

2. April 2013 at 04:40

It seems to me there are two things that are quite important.

1) There needs to be some form of immediate triggering mechanism which in my view is primarily an imbalance between expected short term supply and demand.

2) There is a large hysteresis effect.

2. April 2013 at 04:52

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, Commodity prices rise almost immediately, consumer goods and service prices rise more gradually.”

What would the historical commodity price data have to look like if commodity prices did not rise somewhat almost immediately, but rather rose over a somewhat longer length of time, say in the weeks and months lengths of time?

2. April 2013 at 07:46

Scott:

“what if they double the money supply, AND have the assets to back it up, and announce it will be permanent. I say prices double. What say you?”

I say that an offsetting amount of some other money (checking account dollars, credit card dollars, coins, etc) will reflux to its issuer, and the dollar will hold its value.

What if we live in a world where there are no other moneys to reflux? In that case the newly-issued dollars will try to reflux to the fed, but finding all reflux channels closed, people will think as follows: (1) The fed used to have 100 oz worth of assets backing $100. (2) They now have 200 oz worth of assets backing $200, so each dollar should still be worth 1 oz., but (3) the fed refuses, now and forever, to let that unwanted $100 reflux. (4) This is tantamount to a 50% default by the fed, so the extra 100 oz worth of assets might as well be at the bottom of the ocean, so (5) the dollar will lose half its value.

2. April 2013 at 20:09

“My best guess is that the public (correctly) believes that if and when currency is replaced by electronic money, the government will redeem the currency they pull out of circulation for some sort of alternative asset with roughly the same purchasing power.”

So why aren’t demand deposits considered electronic money with roughly the same purchasing power as currency?

For example, $800 billion in currency, $200 billion in central bank reserves, and $6.2 trillion in demand deposits. Next, no one wants currency anymore. They go to say JP Morgan bank branches and deposit the currency at the bank(s) in exchange for demand deposits 1 to 1 (markup of a checking account). With a 10% central bank reserve requirement and a positive fed funds rate, it most likely becomes $0 in currency, $280 billion in central bank reserves, and $7.0 trillion in demand deposits. In both cases, MOA/MOE equals $7.0 trillion.

I’d have to check with the accounting people, but if there is no demand for currency and the central bank reserve requirement went to 0%, it could become $0 in currency, $0 in central bank reserves, and $7.0 trillion in demand deposits.

3. April 2013 at 16:39

dtoh, I’ll see what I can do.

Geoff, I don’t understand the question.

Mike, OK, That’s a clear difference. Then I need to look at the data and see which model seems to fit best.

Fed up, What happens to the other $720 billion in currency? If the Fed removes it from circulation while keeping the price level fairly stable, then we agree.

3. April 2013 at 18:33

Depends on what you mean by circulation. I’m going to assume all the vault cash (currency) becomes central bank reserves 1 to 1. Now there is $1.0 trillion in central bank reserves. Too many central bank reserves causes the fed funds rate to fall towards zero. The fed removes $720 billion of them to stabilize the fed funds rate.

Now there is $0 in currency, $280 billion in central bank reserves, and $7.0 trillion in demand deposits.

1) Central bank reserves don’t circulate in the real economy and with $0 in currency, something else is circulating.

2) Currency at the fed, currency as vault cash, and currency “under the mattress” all have a velocity of zero in the real economy.

3) The fed is not keeping the price level stable. That is mostly happening in the private sector. I’m assuming the velocity of demand deposits and currency are the same.

4) Lastly and the most interesting case, lower the central bank reserve requirement to zero. Now there is $0 in currency, $0 in central bank reserves, and $7.0 trillion in demand deposits. The $200 billion in central bank reserves were not all held for checking accounts (I believe savings accounts and CD’s have a zero central bank reserve requirement).

4. April 2013 at 08:38

I’m late to this practicum but would like to get up to speed.

Has Prof. Sumner defined the term “money”? And explained why economists find something special about “base money”?

For me, “money” is anything my creditors will accept in payment of my debts. I pay Comcast with a check written on my bank checking account. At the grocery store I swipe my credit card. I pay my real estate taxes with a “check” drawn on my Vanguard Long-Term Treasury Bond Fund. Recently, I loaned my niece the down payment on her house; I used a “check” written on a Vanguard short-term bond account.

Are those transactions examples of the use of “money”? Why is the concept of “base money” important?

4. April 2013 at 17:28

Fed up, I’m afraid I don’t follow your argument.

ellen1910, I generally define money as the monetary base. The base is important because the Fed has a monopoly on it’s production, it can be produced at zero cost, and it’s the medium of account. Thus Fed policy drives NGDP and other nominal aggregates.

4. April 2013 at 19:37

ssumner, which part?

ellen1910, ssumner says medium of account (MOA) is the monetary base (currency plus central bank reserves). I believe MOA is currency plus demand deposits along with medium of exchange (MOE). I believe ssumner would say fed policy is about the monetary base and that banks and bank-like entities don’t expand purchasing power for goods/services and/or financial assets. I believe that banks and bank-like entities do expand purchasing power for goods/services and/or financial assets. Thoughts on those?

7. April 2013 at 16:30

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, I don’t understand the question.”

OK, I’ll try to rephrase it:

You argued commodity prices rise “almost immediately.”

My question is essentially how did you conclude this? If you’re looking at historical commodity price data, how do you know you’re looking at commodity prices that rise “almost immediately” after money changes, rather than “gradually over longer periods of time” after money changes?

What would commodity price data have to look like if the theory that commodity prices rise “gradually and over longer periods of time” is true?

8. April 2013 at 01:58

[…] Money and inflation, pt 5: It’s (almost) all about […]