Memories of the Eisenhower Administration

Paul Krugman argues that we need to look at the cyclically-adjusted budget deficit. And it doesn’t even matter if we have a humongous cyclically-adjusted deficit, as long as the national debt is not rising as a share of GDP. And even then it’ s not really a deficit problem, it’s a lack of health care financing reform problem:

So CBO is now out with its latest report on automatic stabilizers. It estimates that in fiscal 2013 these stabilizers will amount to $422 billion, accounting for just about half of a projected $845 billion deficit. So the cyclically adjusted deficit will be $423 billion.

How does this compare with the deficit consistent with fiscal sustainability? Well, there’s about $11.5 trillion in federal debt in the hands of the public. A reasonable, indeed fairly conservative guess is that nominal GDP will in future grow by 4 percent per year, half from real growth and half from inflation. This means that the sustainable deficit is 4 percent of $11.5 trillion, or $460 billion. Hey, we’re there!

. . .

Yes, late this decade deficits will start to rise again thanks to rising health costs and an aging population, yada yada. But I have yet to hear a coherent argument about why the long-term problem of paying for the benefits we want “” which will eventually have to be resolved through a combination of cost savings and revenue increases “” should constrain our fiscal policy right now, in the midst of what remains a terrible economic slump.

These are all defensible arguments (although I’d feel more comfortable if he’d been making them during the Bush administration.) But I have a nagging feeling that he might be underestimating the challenge ahead of us. Before making that argument, let me say that I agree with Krugman’s claim that the recession is currently a much more pressing problem, and that we need more demand stimulus (although obviously I’d prefer the Fed to do the job–partly for reasons that will later become clear.)

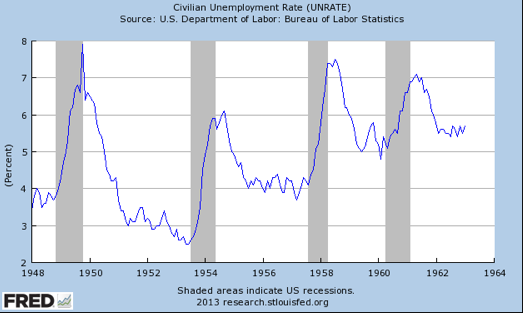

One of my nagging doubts has to do with the nature of the modern business cycle. Krugman sometimes points to the 1950s as a sort of golden age, where income was much more equal that today. But it was also different in terms of the frequency of business cycles; there were three during the Eisenhower administration alone:

I doubt there’ll be any recessions during Obama’s 8 years of office, at least if you attribute the 2007-09 recession to Bush. But in another sense Obama might preside over 8 years of continuous recession–with unemployment staying stubbornly high.

Does that affect Krugman’s argument? I’m not quite sure. We’ve never gone more than 10 years without a recession, and it’s already 5 years since the 2008 recession, with no end in sight for high unemployment. If we have another recession in 2018, and the deficit gets massively larger, how reassuring will Krugman’s “cyclical deficit” argument seem? If the debt/GDP ratio levels off in good times and rises in bad times, are we building a (debt) stairway to heaven?

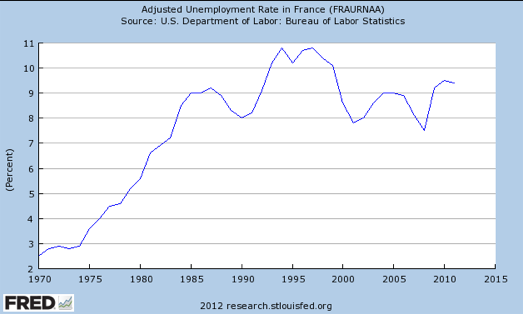

Now let’s go from one extreme to the other, from the Eisenhower administration to modern France:

As you can see France never really recovered from the two oil shock recessions. They’ve had nearly 30 years of unemployment fluctuating around the 8% to 10% range (it’s currently 10.5%) Or maybe they did recover and what actually happened is the natural rate of unemployment rose to 9%. They’ve been cycling around a new and much higher natural rate.

Why did this happen? The progressive answer (lack of AD) doesn’t really work, as other European countries with similar AD policies have far lower natural rates. “Big government” is probably too simplistic, as some other European countries with big government have much lower unemployment. Still, I’m more sympathetic to the supply-side explanations, which look at a wide range of labor market distortions.

I’m not predicting that we’ll follow in France’s footsteps, indeed I expect the unemployment rate to fall well below 7% if we return to 26 weeks maximum UI. But I do think we’ve got serious structural problems, a combination of a slightly higher natural rate of unemployment, more disability, and lower productivity growth (for reasons explained by Tyler Cowen and Robert Gordon.) I lived through an earlier period where we were continually being surprised by bad news on the supply-side, and wouldn’t be surprised if it happened again.

Overall, I don’t think we are Eisenhower America, nor do I think we are France, rather somewhere in between. If anything, I might be even more optimistic than Krugman about the persistence of low government bond yields, so I don’t see any imminent debt crisis ahead. On the other hand I also think it might be harder to keep debt at a manageable level than Krugman assumes, as his “cyclically adjusted deficit” concept was actually developed for a 1950s-type business cycle, where you eventually returned to the old trend line.

Why have the last three recoveries been so slow? Some people talk about factors like “financial problems”. But that confuses real and nominal factors. The RGDP recoveries have been slow because the NGDP recoveries have been unusually slow (compared to the 1950s, or just about any other decade.) So the real question is; why have the NGDP recoveries been so slow? It might be partly intentional—the Great Moderation and all. Fast recoveries might trigger another recession. But I think it’s also partly mistakes in monetary policy. Obviously in this case the zero bound played a role, but the deeper explanation is that real interest rates have been steadily falling since 1983, from 7% to less than zero. And this is precisely when the slow recoveries started. The Fed isn’t easing as much as it thinks it’s easing in each recovery, because they have continually underestimated how much the (Wicksellian) equilibrium real rate of interest has fallen. Thus they’ve overestimated how much monetary stimulus they’ve provided. It’s all John Taylor’s fault. (Just kidding.)

PS. My previous post on this topic was called “Staircase to Heaven.” I really am getting senile.

Tags:

11. March 2013 at 06:52

I think low points on the business cycle and the relative ease of firing workers (unlike, say, France) makes it much easier to replace labor with capital. Even with consistently higher unemployment, wages share of GDP has been consistent across Europe (except Italy). And above 50% except Italy and Spain.

Whereas the USA has fallen steadily through the postwar era.

11. March 2013 at 06:58

And even if the ‘new trendline’ is worse, unless it’s going to keep shifting down, the 1950s business cycle theory for cyclical-deficits works. Sure, it changes our perspective of the current deficits etc. but it still doesn’t change the point that cyclical deficits will come down.

Also – and this isn’t good for the worker – I don’t think worker productivity growth will be the same as it once was, but I do think capital productivity will continue to increase. This isn’t good for inequality, but I think modern networks will have a huge effect on future growth. I wouldn’t say I’m an optimist for the ‘good-ole postwar America’, but I do think what we don’t see in greater output per worker-hour, we will see in capital output.

11. March 2013 at 07:09

Interesting post. Lots of good points.

——————-

Krugman wrote:

“But I have yet to hear a coherent argument about why the long-term problem of paying for the benefits we want “” which will eventually have to be resolved through a combination of cost savings and revenue increases “” should constrain our fiscal policy right now, in the midst of what remains a terrible economic slump.”

Perhaps Krugman should seriously consider the possibility that his theory prevents any argument, however coherent and plausible, from being judged by him as coherent.

When your theory is that economic thinking turns upside down during recessions, when you believe there is nothing more important than stopping current recessions, then no amount of pleading to long term issues will convince you otherwise. It’s not that there are no coherent explanations (since they exist), it’s that they just aren’t being identified as such by those wedded to the theory that stopping current recessions via government inflation and spending is priority numero uno.

11. March 2013 at 07:11

Dear Blog Commenters,

A gold nut buddy of mine is claiming that the Fed has chosen to buy mortage backed securities in order to help out the big banks. He says that the MBS purchased by the Fed are “toxic assets” and they are overpaying for them at uncompetitive prices.

You can find a similar argument here:

http://www.opednews.com/articles/QE-Infinity-What-It-s-It-by-Ellen-Brown-121004-141.html

and elsewhere.

I’m 99% sure that his story is a massive myth. Are there any good sources of data that show that the Fed is buying MBS that are (1) relatively safe and (2) highly liquid and traded fairly frequently?

Also, why has the Fed chosen to buy MBS along with its regular purchases of U.S. treasuries?

11. March 2013 at 07:25

Someone needs to sponsor a John Taylor, Scott Sumner lunch. John is the king of rule based policy but he is hung up on the idea that the Taylor rule is the specific right rule. Indeed, the Taylor rule with its twin gaps touches on just the right issues but fails because it is a proportional control law and has a persistent error.

If only John could be convinced his rules is the wrong one.

Btw, I have a lot of respect for John, he came out strongly in 2008 that the Fed was focused wrongly on liquidity when it should have been focused on loosening policy to stave off insolvency due to collapsing output.

Somewhere between here and there his mind failed him though. I blame politics.

11. March 2013 at 07:30

TravisV:

“I’m 99% sure that his story is a massive myth.”

I am pretty sure that MBS of which the underlying homeowners are defaulting on their payments, or where the equity value of the homes plummets, are indeed toxic.

I’m pretty sure it isn’t a gold bug theory, but an economic one.

11. March 2013 at 07:32

TravisV:

“Also, why has the Fed chosen to buy MBS along with its regular purchases of U.S. treasuries?”

See “the gold bug” theory you alluded to earlier.

11. March 2013 at 08:02

Travis, I think it’s a myth. I seem to recall those MBSs are backed by the Treasury. Perhaps someone who knows can chime in.

11. March 2013 at 08:08

‘Pollyanna Krugman and the Last Crusade’, maybe.

11. March 2013 at 08:08

As Sachs warned the other day, in a decade or two debt service is going to cost more than defense+discretionary. That should scare the hell out of every sane person.

Lately I’ve been worried this scenario will unfold: the Fed will target 5% NGDP growth, we’ll get growth, interest rates will rise, the interest expense of all the short-term debt the gov’t carries will spike, and the Fed will find itself under enormous pressure to monetize federal debt at a time when they are trying to keep on lid on NGPD growth.

11. March 2013 at 08:10

Fed MBS purchases:

http://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/ambs/ambs_faq.html

11. March 2013 at 08:43

Krugman’s position all along is that it’s much easier to deal with structural problems at full employment than it is in a depressed economy. I think ( or at least hope) Scott agrees with this point. But sometimes it’s unclear, such as in posts like this one.

11. March 2013 at 09:07

” The Fed isn’t easing as much as it thinks it’s easing in each recovery, because they have continually underestimated how much the (Wicksellian) equilibrium real rate of interest has fallen. Thus they’ve overestimated how much monetary stimulus they’ve provided.”

You saved the money quote for the end. I agree on the equilibrium real rate, but would add that they’ve underestimated the monetary restriction they’ve provided during booms. Does anyone still think that 5.25% fed funds during a housing bust was the correct policy? Imagine if the Fed raised rates by 4.25% in 2 years like they did in the last cycle.

11. March 2013 at 09:33

‘Krugman’s position all along is that it’s much easier to deal with structural problems at full employment than it is in a depressed economy.’

But he’s probably wrong about that. Europe’s situation doesn’t support it, and it’s getting too obvious to ignore;

http://www.voxeu.org/article/european-labour-market-reform

‘Excessively strong employment-protection legislation insulates the insiders – well-established employed workers on permanent contracts – from labour-market pressures, while the outsiders fill a succession of temporary, unprotected jobs and bear the brunt of business-cycle shocks: employment-protection legislation needs to be reformed to remove the sharp divide between workers on different types of contracts, and to lower the cost to employers of making severances.’

The pressure of absurdly high unemployment in several countries right now ought to make it easier to reform, not harder.

11. March 2013 at 12:11

TallDave,

Thanks a lot, man!!!

11. March 2013 at 12:35

France declared war on AS in the 80s, or so I read. Mitterand had a coalition with the communist at the start! When one looks France’s non-tax Herritage index components it really is remarkable that they only have 10% unemployment and have made it this far through the Euro mess. A lot of wasted potential.

11. March 2013 at 12:40

Patrick,

High unemployment reduces the bargaining power of workers. So of course those looking to shred worker-security programs will have more success during periods of high unemployment.

But when I say “structural problems,” I mean things like skill mismatches, climate change, and the trade deficit. These things would probably be easier to address if we got growth back in the short run.

11. March 2013 at 13:28

Dr. Sumner:

“I seem to recall those MBSs are backed by the Treasury.”

Ginnie Mae’s MBS were fully backed by the Treasury, but neither Fannie Mae nor Freddie Mac’s MBS were so backed. But the latter two institutions did have a direct line of credit to the Treasury, so there was a perceived de facto treasury backing to those MBS.

However, MBS were still considered risky investments unlike treasuries, and investors priced the risk in terms of payment default, pre-payment, and equity tranch value.

Banks long in Fannie and Freddie MBS owned securities that if the borrowers defaulted, the banks would take ownership of the underlying property. But if the property value declines, the MBS value declines. I believe this is why Fed purchases of those MBS at their NON-MARKED TO MARKET estimated values, can be considered a backdoor bank bailout.

11. March 2013 at 14:33

Patrick,

What if thats what French voters want? An AD crisis shouldn’t be forced upon them by the ECB just to get them to change their minds about unemployment insurance or other labor market protections. If the right in Europe want more flexible labor markets then they should make that case to the public and try to win elections, not cram it down their throats with tight money.

11. March 2013 at 15:32

Regarding:

“As you can see France never really recovered from the two oil shock recessions. They’ve had nearly 30 years of unemployment fluctuating around the 8% to 10% range…”

I have read so many editorials that place the blame for poor economies and high unemployment on excessive government debt that I have come to believe this is true. France and Japan seem to be poster children for this position.

11. March 2013 at 16:19

I second Steve’s notion that the money quote was saved til the end.

And certainly, if you primary balance in good times and primary deficit in bad times, you’ll ratchet up debt/GDP inevitably. But on this second point, I don’t see how that observation that recessions used to be more frequent is relevant. It arguably could be … but it just reads like an incomplete thought.

Re France: I don’t see any progressives arguing that France has been in a 30 year demand short fall. That looks like a straw man. There’s nothing about “progressive” econ that precludes a movement in NAIRU over time, and I’ve seen many acknowledge the notion that supply side factors (primarily labor market frictions) are a primary culprit. Maybe not loudly … but still.

One thing I find unfathomable though is the notion that limiting UI benefits to 26 weeks would drop the UE rate “well below 7%.” It would take around 1.3 million additional people employed to get below 7% at all (let alone “well below”). There are according to the BLS 4.7 million total people unemployed for greater than 27 weeks, and many if not most of them don’t even collect UI. I don’t doubt that incentive effects exist related to UI, but this just looks like an implausibly high assumption of their potency, even if we completely discount the contractionary fiscal effects of not paying those benefits.

Regarding Krugman: I don’t think his view is that “it doesn’t even matter if we have a humongous cyclically-adjusted deficit,” but rather how the small structural deficit is a further reason why we shouldn’t be panicking about deficits in the short run and enact cuts at the expense of growth. Those aren’t quite the same thing.

11. March 2013 at 19:46

but neither Fannie Mae nor Freddie Mac’s MBS were so backed.

Then why are taxpayers paying tens of billions in Fannie and Freddie losses?

My understanding is that they swore up and down, in the charter and the chatter, that the federal government was not backing them, but no one ever believed that and when the chips were down it wasn’t true.

11. March 2013 at 20:00

[…] See full story on themoneyillusion.com […]

11. March 2013 at 22:31

Geoff is very gullible. He continues to lose credibility.

As TallDave’s links illustrate, the Fed isn’t even buying old MBS’s that the big banks have been extending and pretending. They’re buying newly-issued MBS’s.

Second, I really, really doubt that there’s any evidence whatsoever that Fannie or Freddie–much less the Federal Reserve–are currently purchasing any super-risky subprimeish MBS’s.

11. March 2013 at 22:43

And then there’s the notion that the Fed is “overpaying” for the MBS’s. No, the Fed is paying market prices. If you look here:

http://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/ambs/ambs_faq_09132012.html

the Fed says “Agency MBS transactions will take place in the secondary market through a competitive bidding process and in line with standard market practices.”

12. March 2013 at 04:11

Re cyclically-adjusted deficits: this seems remarkably similar to the policy introduced in the UK in 1997 by Gordon Brown. The results weren’t very impressive. Not only did Brown mistake an economic bubble for “real” growth (which meant he could continually raise spending – until the chickens came home to roost) but when the budget didn’t quite balance over the economic cycle he conveniently changed the dates of the cycle! The moral is: politicians will always fudge the rules and the data, if it suits their purposes.

12. March 2013 at 06:06

JSeydl, Yes, I fully agree.

Steve, I think the 5.25% interest rate during the housing boom was a reasonable policy. I don’t favor interest rate targeting, but it’s not obvious to me that the rate should have been different.

Geoff, You are wrong, the Treasury began backing those bonds a few years back.

Sanjait, The point was that we’d quickly recover, so the cyclical deficits weren’t much of a problem in the 50s. But if we never recover, like France, then how reassuring is it when someone says the deficit problem will go away when we recover?

I should have made that argument clearer.

You said;

“I don’t see any progressives arguing that France has been in a 30 year demand short fall.”

I think Yglesias might make that argument. I’ve seen other progressives make it, sometimes combined with hysteresis.

You misread my UI comment. I did not suggest the rate could not fall below 7% with extended UI. My point was that returning to 26 weeks makes a fall below 7% extremely likely. I agree that the effect is probably modest (I’ve suggested 50 to 100 basis points.

Regarding the last quote in your comment, you took it out of context. Krugman says big deficits don’t matter if the ratio of debt to GDP is stable.

Bill, Good point.

12. March 2013 at 21:33

“I think Yglesias might make that argument. I’ve seen other progressives make it, sometimes combined with hysteresis.”

I’m not old enough to know what all was said in the early 90s, but I can tell you that a 30 year demand shortfall is not in the present “the progressive answer” to why France has has had persistently high unemployment. Yglesias says some strange things, so I wouldn’t put it past him to say something like that, but he doesn’t represent progressives any more than some random conservative blogger’s statement represents all conservatives. I’m what most would call progressive, and well read, and I’ve never seen anyone make this claim you attribute to progressives.

“You misread my UI comment. I did not suggest the rate could not fall below 7% with extended UI. My point was that returning to 26 weeks makes a fall below 7% extremely likely. I agree that the effect is probably modest (I’ve suggested 50 to 100 basis points.”

I read it just fine. I don’t think that kind of drop is plausible simply by eliminating extended UI. The numbers don’t make sense even if you ignore fiscal effects. You’d need roughly half of everyone on extended UI to get jobs solely due to the loss of benefits and then not offset the jobs of everyone else. Contrary to conservative mythology, the majority of people on UI aren’t there from lack of motivation.

“Regarding the last quote in your comment, you took it out of context. Krugman says big deficits don’t matter if the ratio of debt to GDP is stable.”

Interesting you think I took you out of context somehow. That’s what I was accusing you of doing with Krugman, and it looks like you still are. He’s said specifically that debt to GDP needs to be stable *in the long run*. The fact that this isn’t re-emphasized with every single one of the many mentions of the topic doesn’t mean his view has changed, and when you leave off that key caveat, it completely changes the meaning.

13. March 2013 at 04:53

sanjait, I’d be very interested in what you think is the “progressive explanation” for France’s high unemployment. Something tells me it will be inconsistent with the rest of your post.

You said:

“I read it just fine. I don’t think that kind of drop is plausible simply by eliminating extended UI.”

You obviously did not “read it just fine,” as this misrepresents what I said. I did not say eliminating extended UI will cause a large drop in unemployment, I said if it is eliminated unemployment will end up below 7%. That’s perfectly consistent with ending UI only causing a 0.2% drop in the unemployment rate, and the rest occurring for other reasons.

You said;

“Contrary to conservative mythology, the majority of people on UI aren’t there from lack of motivation.”

I don’t accept the premise of your statement that more than half of the people on extended UI would have to be lazy for my claim to be correct.

I would also like to see your academic study of the motivation of people on extended UI. The program only began in 2009. I very much doubt any such academic studies have been published. I lived in Britain in the 1980s and my impression was that most of the long term unemployed were there due to the disincentive effects of UI. BTW, claiming that UI has a disincentive effect on work in no way implies that the unemployed are lazier than the employed, contrary to the widespread opinion of liberals.

I agree that Krugman believes the debt ratio must level off, and I certainly mentioned this in the post. Indeed the post focused on that very topic. I think my summary correctly characterized his views, although readers may differ. Unlike Krugman, I quoted the exact paragraphs that I summarized. As you know, Krugman doesn’t do this when he mischaracterizes the views of others.

14. March 2013 at 18:22

I think a truly senile person would say “stairlift to heaven”.

23. March 2013 at 09:39

TravisV:

“He continues to lose credibility.”

Wouldn’t that imply that you or someone has shown I have been losing “credibility” up until this point?

“As TallDave’s links illustrate, the Fed isn’t even buying old MBS’s that the big banks have been extending and pretending. They’re buying newly-issued MBS’s.”

The Fed has been buying MBS for many years, old and new. I was talking about the past, when things were different.

“Second, I really, really doubt that there’s any evidence whatsoever that Fannie or Freddie-much less the Federal Reserve-are currently purchasing any super-risky subprimeish MBS’s.”

The term “super risky” is open to interpretation. I didn’t use it.

Dr. Sumner:

“Geoff, You are wrong, the Treasury began backing those bonds a few years back.”

Not when the Fed originally starting buying the MBS, which was my point. It’s why I explicitly used the term “were”, to denote historical facts.