Magnetic Hill, and the mystery of the jobless recoveries

Back in the 1970s I was driving near Moncton, New Brunswick when I came across Magnetic Hill. Cars in neutral seem to roll uphill, perhaps due to an optical illusion. I’m going to argue that this strange hill may provide an explanation for the mystery of the last three recoveries, which have been widely labeled “jobless recoveries.”

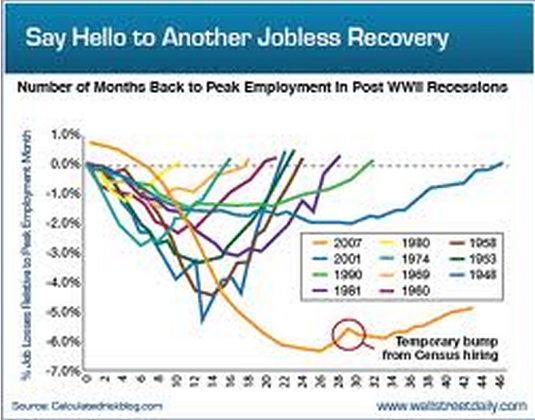

The last three recoveries have been shaped like frying pans, not the V-shape that previously occurred. Most of the explanations I see posit deep structural changes in the economy, and in particular the nature of labor markets. But those theories actually fail on two different levels. First, structural change is very gradual, and we suddenly went from V-shaped to pan-shaped recoveries. More importantly, the real question is not why have robust recoveries in NGDP not led to rapid job growth, but rather why have we not had the usual rapid recoveries in NGDP.

In other words, monetary policy has been relatively tight during the past three recoveries, and hence NGDP growth has been slow. Thus it’s no surprise that we’ve have very slow recoveries in the labor market.

But why have the recent recoveries in NGDP been so slow? Hasn’t monetary policy improved during the “Great Moderation?” Isn’t the business cycle more stable? (At least before 2008?) Yes, monetary policy has improved, but it is still slightly flawed, and that flaw led to an asymmetric bias. Policy was very good at preventing overheating–and hence the recoveries tended to be longer after the 1982 recession, but policy was not so good at promoting a brisk recovery.

So how does Magnetic Hill explain this mystery? Suppose Magnetic Hill is caused by an optical illusion, which makes it seem like you are going uphill, when you are actually going downhill. You’d then put too much pressure on the accelerator in one direction, and too little in the other. Now suppose that since 1983 some sort of mysterious force caused monetary policy to be less expansionary that the Fed anticipated. In that case they’d usually have a more contractionary policy than they wanted, which would extend booms (by preventing overheating) but also slow recoveries from recession. That could explain why money was too tight during the last three recoveries, producing sub-optimal NGDP growth and suboptimal jobs growth.

Nice theory, but do I have any evidence for this mysterious “magnetic force” throwing off monetary policy since 1983. Yes I do!! Recall that NK policy works through adjusting the market interest rate relative to the unobserved Wicksellian equilibrium rate. In practice, all we can do is look backward and estimate the Wicksellian rate by observing actual market rates in relation to the growth rate of prices and output. So in practice economists tend to assume the Wicksellian equilibrium real interest rate is fairly stable, at least averaged over the cycle.

So my theory of a mysterious force causing three consecutive jobless recoveries requires the economics profession to consistently overestimate the Wicksellian equilibrium real interest rates over a period of 30 years. How likely is that?

Perhaps more likely than you’d think. Suppose economists assumed the rate showed no long run secular trend, but in fact a major downward secular trend began in 1983. In that case the Fed would almost always be overestimating the expansionary stance of its policy, producing a bias toward ever lower rates of inflation and NGDP growth. This wouldn’t be much of a problem during booms, after all the Fed was usually too expansionary during booms in earlier decades. But in recessions it would lead to slow recoveries, even if they seemed to be adopting highly expansionary policies.

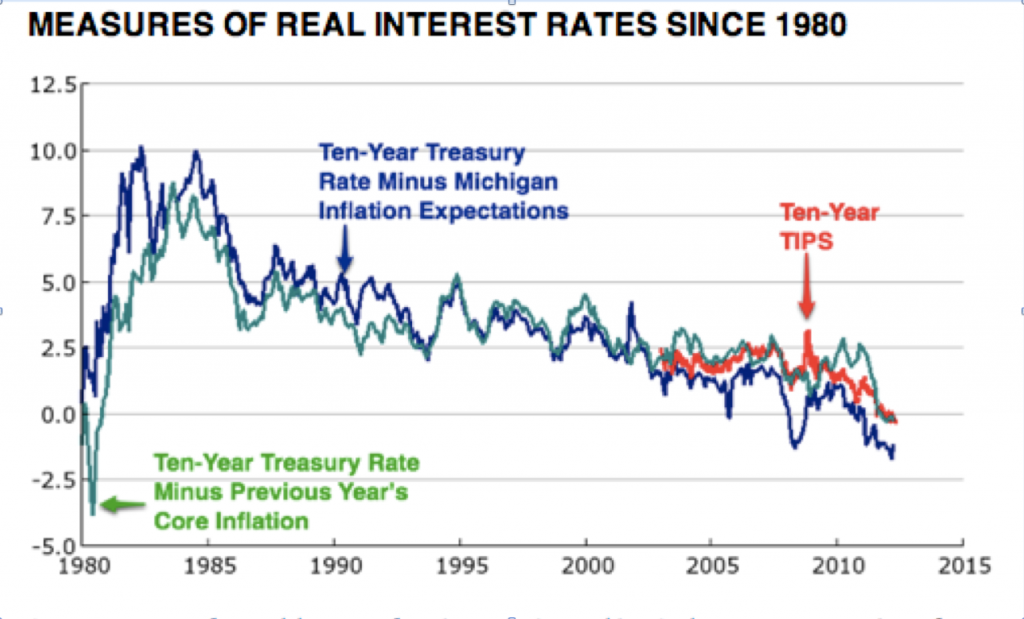

Is there any evidence for a long downward secular trend in real interest rates since 1983? Yes, there is, indeed this is probably the most notable stylized fact of recent American macro history:

Real interest rates on 10-year T-bonds have fallen from 7% to less than zero percent over the past 30 years. Yes, those are market rates, not Wicksellian equilibrium rates. But since both inflation and NGDP growth have fallen sharply over that 30 year period, the decline in the Wicksellian equilibrium rate must have been even greater!!

It’s only in retrospect that the full importance of this earth-shaking trend has begun to sink in. The Fed has now realized that low rates aren’t enough, and have moved toward more aggressive stimulus. Ditto for the Japanese. Stock investors now realize that low rates are not simply a cyclical pattern, but at least partially reflect a deep secular trend. That means equity prices needed to be adjusted upward, and the process is well underway. In fairness to my progressive friends, infrastructure projects that were not cost effective in 1983, suddenly are cost-effective in 2013, even if not used to stimulate the economy.

Low interest rates are the new normal, we all better learn to get used to it.

PS. Bill Woolsey sent me a paper by an MIT economist named Ivan Werning, which starts out as follows:

The 2007-8 crisis in the U.S. led to a steep recession, followed by aggressive policy responses. Monetary policy went full tilt, cutting interest rates rapidly to zero, where they have remained since the end of 2008. With conventional monetary policy seemingly exhausted, ï¬scal stimulus worth $787 billion was enacted by early 2009 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

I don’t doubt that this is an excellent paper, but the intro annoyed me for several reasons. Werning is expressing the conventional wisdom about interest rates in late 2008, but in fact the Fed was shamefully slow to ease policy. A Svenssonian “target the forecast” approach would have forced the Fed to cut rates fast enough so that expected NGDP growth was always on target. And yet rates didn’t hit zero until mid-December 2008, by which time it was obvious to everyone that we were in a severe recession. The Fed did not even cut rates by a measely 1/4% in the meeting of mid-September 2008, 2 days after Lehman failed. They weren’t targeting the forecast.

And in 2008 we were teaching our students that monetary policy is “highly effective” at the zero bound (in the number one money textbook, by Mishkin), so I can’t imagine why zero interest rates would imply a need for fiscal stimulus.

PPS. Paul Krugman zeros in on a similar argument, from a slightly different direction. All I’d add is that while a 4% inflation target would be better than a 2% inflation target, a 5% NGDP growth level target would be far better than either inflation target.

Tags:

29. May 2013 at 09:36

Professor Sumner,

Any explanation for the fall in the equilibrium real rate? Lower levels of discounting? Less productive capital? More uncertainty about the future/precautionary saving?

29. May 2013 at 09:46

Was going to suggest you also look up the Santa Cruz Mystery Spot, but found that the list of mysterious hills around the world is much more extensive:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_gravity_hills

29. May 2013 at 09:51

Speaking as a Canadian Maritimer, I appreciate the hat tip to Moncton and Magnetic Hill – the underwhelming wonder of the world.

29. May 2013 at 09:53

J

My bet is on the global savings glut – a term coined by Bernanke.

29. May 2013 at 10:08

I believe you are downplaying the importance of fiscal policy. Congress in each case significantly lowered the cost of capital by adjucting depreciation rates. This combined with labor becomming relatively more expensive in relationship to capital has convinced Operations managers to restructure their operations even in a recession.

This behavior is a real change in corporate behavior.

29. May 2013 at 10:15

Great post. The second graph is one we don’t see often enough.

29. May 2013 at 10:32

Prof. Sumner,

Neil Irwin just responded to you:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/05/29/the-feds-been-keeping-the-economy-afloat-thats-the-problem

“Jared Bernstein, Scott Sumner and Ezra say I should have mentioned an important reason: the apparent success of the Federal Reserve’s policies, introduced last September, of pumping more money into the economy and pledging to keep rates low even after the economy improves.

They’re right! But that may not be a good thing.

……

The bad news, though, is that these channels through which monetary policy affects the economy tend to offer the most direct benefits to those who already have high incomes and high levels of wealth.”

29. May 2013 at 10:39

“Most of the explanations I see posit deep structural changes in the economy, and in particular the nature of labor markets. But those theories actually fail on two different levels. First, structural change is very gradual, and we suddenly went from V-shaped to pan-shaped recoveries.”

1\. Problems with the stucture of the economy do not always manifest in the same “shape” to employment changes over time. Sometimes the structural problems manifest in sharp and steep unemployment, sometimes more shallow. It depends on the extent and pervasiveness of malinvestment.

Never reason from an unemployment change.

“More importantly, the real question is not why have robust recoveries in NGDP not led to rapid job growth, but rather why have we not had the usual rapid recoveries in NGDP.”

2\. Because we don’t have city level NGDP targeting.

More seriously, NGDP is not the engine of economic recovery. In a free market, it is a consequence of economic recovery. In a monopolized money market where an artificial target is imposed, it is a hampering of economic recovery.

29. May 2013 at 11:07

Scott,

I agree with you that slow NGDP growth is a likely cause of our slow recovery.

I know this is kind of off topic, but paul Krugman just put out a new blog post http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/05/28/taxing-the-rich/

where he mentions he is doing a debate with Arthur Laffer on what the top marginal rate should be.

He references the economic policy institute, which is obviously a biased source, but he also mentions the work of Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, who assert that the revenue maximizing top tax rate is 70-83%!

Obviously ridiculous, but I’m curious as to how? What’s the flaw in their studies?

Maybe you can do a post on it sometime

29. May 2013 at 11:16

J, Several theories, all may play a role:

1. Less capital investment in the service/information economy than the old manufacturing economy.

2. Slower population growth in much of the world. Note that interest rates are relatively high in Australia, which as relative fast pop. growth, and vice versa for Japan.

3. Growing importance of high saving Asian nations.

4. Tyler Cowen’s Great Stagnation thesis.

Of course the current very low rate is partly cyclical, but not the 30 year trend.

mobile, Interesting.

Sam, Very few American have even heard of Moncton. Of course Americans are notoriously ill-informed about Canada.

Mike, How does that connect with NGDP growth?

TravisV, Needless to say I don’t agree. But even if it did, it also offers benefits to the unemployed.

29. May 2013 at 11:21

Edward, That Krugman claim is very misleading, which of course is typical. They argue that the top rate is around 70% to 83% in a system with no loopholes. So those numbers have no relevance to the US economy. The optimal top rate for the US is far lower in their study–I believe around 50%.

I happen to believe the optimal top income tax rate is zero, and the optimal top consumption tax rate is around 50% to 70%, although that’s just a wild guess.

If you use my search box you will find a number of posts on Saez, including one entitled “Journal of Economic Propaganda.”

29. May 2013 at 11:37

Scott,

thanks

29. May 2013 at 12:12

“The optimal top rate for the US is far lower in their study-I believe around 50%.”

The Netherlands currently has a top rate of 52 percent on “ordinary” income (rates on (deemed) investment income are lower).

A government study by the Central Planning Bureau was released today that concluded the optimal revenue-raising rate is 49 percent. Is that a coincidence, or do they read The Money Illusion?

http://www.cpb.nl/persbericht/3213502/geen-extra-belastinginkomsten-door-hoger-toptarief

Press release is in Dutch.

29. May 2013 at 12:23

Back in 1990 they started having conferences on the “Conduct of monetary policy in a low interest rate environment”.

Instead of learning something from all the discussion over these years, they “doubled down” with the ‘old methods’.

The result is “Chilling”:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2013/04/15/chilling/

29. May 2013 at 12:33

Wait, do libertarians know that the Netherlands have a Central Planning Institute? And I hear Cato praising the Dutch all the time…

29. May 2013 at 12:34

One thing that strikes me as inconsistent is the view that NGDP-LT is a bad thing in large part because NGDP is subject to revision. But the NK´s are quite content with depending on unobservables. Things like the Wicksellian equilibrium rate and output gap!

29. May 2013 at 13:29

Edward: “revenue maximizing top tax rate”

You’ve already mostly lost, if you accept the framing that the “optimal” tax rate is that which maximizes (short-term) government revenue.

Instead, for example, we might want to maximize long-term economic growth (which probably maximizes long-term government revenue). There is no reason, in principle, why the tax rate that maximizes growth, should be identical to the tax rate that maximizes immediate revenue.

Don’t give in to unexamined question framing. What are society’s goals, in setting a tax rate?

29. May 2013 at 18:01

Marcus Nunes,

You wrote a phenomenal post on this very subject a couple years back:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2011/02/22/bernanke%C2%B4s-gsg-hypothesis-a-cop-out

29. May 2013 at 23:07

Saturos,

You do not need a Central Planning Bureau (Centraal Planbureau) when you’ve got a Congressional Research Service, a Joint Committee on Taxation, the CBO, the OMB, The Council of Economic Advisors, the National Economic Council, Treasury Dept economic staff, etc., etc.

The pragmatic Dutch seem to get along just fine with much less.

30. May 2013 at 03:54

Scott: yep. I’ve been on the CD Howe’s Monetary Policy Council for a few years (the Canadian shadow monetary policy committee). Originally we used to think that 5% was the normal average nominal interest rate to keep inflation at 2% target. Then I had to argue that “4% was the new 5%”. Then I had to argue that “3% was the new 4%”. Even a couple of years back, I had to argue that just because the economy would soon return to normal didn’t mean that the overnight rate should return to the “normal” 5%. http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2011/07/taylor-rules-and-the-bank-of-canadas-monetary-policy-report.html

It’s when people use Taylor Rules, and assume that the “constant” term really is constant over time, that we get this problem.

30. May 2013 at 05:29

Thanks Vivian.

Marcus, Yes, and they still seem attached to interest rate targeting.

Nick, Exactly.

30. May 2013 at 13:20

Dr. Summer,

It should be noted that jobs and employees are the enemy of every company in the world. Companies only hire workers when they have no other choice, when they absolutely have to have more employees to maintain their level of profits. As a recession ends, suppliers of goods and services begin to hire workers because they experience increased demand, they need workers to produce the goods and service customers are able to pay for. Failing to hire these workers would mean lost profits. For a while simply hiring more workers is enough to keep up but at some point, capital will have to be expended for the purchase of durable goods and more workers will be needed.

What has been happening increasingly since 1983 is that companies can supply enough goods and services to meet increasing demand without hiring new workers. This is largely because of the export of capital, mostly manufacturing. Instead of hiring workers to produce more goods, those goods can now be produced overseas, either by actually moving facilities overseas or simply contracting out the work to other firms that operate overseas.

The Bank of England [1] recently release a report which touched on this topic. “Today’s [International Monetary and Financial System] has permitted large imbalances to build between countries, particularly over the past fifteen years or so. After having averaged just under 1% of world GDP between 1980 and 1997, net capital flows (measured as either the sum of all countries’ current account deficits or the sum of all countries’ current account surpluses) roughly tripled to a peak of almost 3% of world GDP in 2006-07 (Chart 4). Although imbalances reversed sharply in 2009, they remain high by historical standards and are forecast by the IMF to continue at around 2% of world GDP over the next five years at least. These growing flow imbalances have also been accompanied by growing stock imbalances. Between 1998 and 2008, the US net external liability position quadrupled in size, rising to $3.3 trillion (or 23% of GDP). Over the same period, the net external asset positions of Japan and Germany rose by $1.3 trillion and $0.9 trillion respectively. Chinese data are only available from 2004, but show that net external assets increased by $1.2 trillion, to $1.5 trillion (33% of GDP) in 2008, mirroring the increase in the US net external liability position over this period.”

In other words, capital is fleeing the traditional centers of capitalism, western Europe, the US, and Japan and moving to countries with very low labor costs. When the US economy recovers from a recession now, jobs are indeed created, overseas.

A different way to look at the same phenomenon is to look at monetary velocity. Monetary velocity has been declining. For example MZM velocity peaked around 1983 just shy of 8.5 and now is about 1.4 [2]. M1 had likewise peaked in 1983 at around 7.4 and then went into decline for a number of years, grew again until 2008, but is now at a point less than the 1983 peak (6.5 or so)[3]. M2 followed the same pattern as M1, a peak in 1983 followed by period of decline, a peak in 2008 but now at an all time low of 1.5 [4].

Why is the velocity of money in decline in the United States? There is less economic activity, people are using money less frequently. One reason for this is that there is less capital investment in the United States. When capital is invested, it creates jobs and economic expansion, and money moves accordingly. When capital is not invested, the velocity of money declines.

Jobless recoveries are a result of capital being invested overseas so that increases in production to meet increasing demand does not require additional employees located in the United States.

[1] http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/fsr/fs_paper13.pdf

[2] http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/MZMV

[3] research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M1V

[4] research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/M2V

30. May 2013 at 16:01

David, There is no point in coming over here and dumping a dissertation into the comment section, if:

1. You pay no attention to what I say.

2. You don’t address any of my arguments.

My response is that you are wrong for precisely the reasons I explain in my post.

30. May 2013 at 19:27

David De Los Angeles:

It should be noted that jobs and employers are the enemy of every worker in the world. Workers only hire employers when they have no other choice, when they absolutely have to have more employment to maintain their level of income. As a recession ends, suppliers of labor and services begin to hire employers because they experience increased demand, they need employers to produce the goods and service customers are able to pay for. Failing to hire these employers would mean lost incomes. For a while simply hiring more employers is enough to keep up but at some point, capital will have to be expended for the purchase of durable goods and more employers will be needed.

What has been happening increasingly since 1983 is that workers can supply enough labor and services to meet increasing demand without hiring new employers. This is largely because of the export of capital, mostly manufacturing. Instead of hiring employers to produce more goods, those goods can now be produced overseas, either by actually moving facilities overseas or simply contracting out the labor services to other firms that operate overseas.

31. May 2013 at 05:36

Hi, I’m an economist (not a real one – I work for the FCC destroying the economy rather than studying it), but I am a former student of Tyler’s so I may have learned something. Anyway, I found this post interesting because it plays into something I’ve been thinking for a while. Do you think perhaps that monetary authorities are in some ways limited because the monomaniacal focus on inflation over the past, say 40 years? (A focus that was certainly appropriate 40 years ago.) So, expectations have been created, and the popular aversion to what we would call “easy money” under any circumstances (conservatives freak any time monetary authorities loosen up a bit), and monetary authorities are restrained, both internally and externally from doing anything that would, they think, lead back to the unrestrained inflation of decades ago.

So, I guess I’m arguing for a huge cultural shift that restrains both monetary authorities and the influence of market monetarists and has led to the graphs in this article because the “taking away of the punch bowl” phenomenon is killing recoveries before they really begin.

I’d be curious to see what you think about this. I’m a complete amateur in this area, but an interested one.

31. May 2013 at 07:54

Andrew, Perhaps (although I’d say 32 years, not 40 years). But I still think they would have preferred faster recoveries.

23. June 2013 at 00:00

[…] Source […]

27. July 2013 at 12:20

[…] my “magnetic hill” post I suggested an ad hoc theory of the last three busienss cycles. Long term real rates […]