Low rates don’t cause bubbles

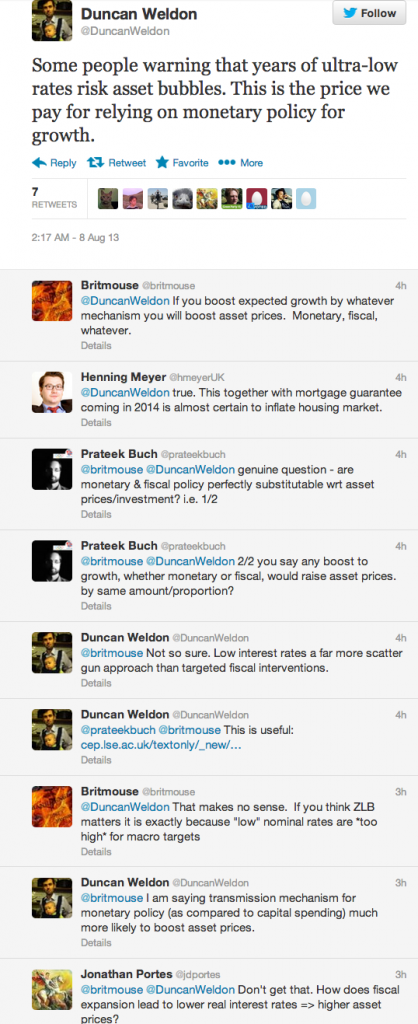

Ben Southwood sent me an interesting debate on Twitter:

Perhaps a good place to start is “never reason from a price change.” Asset prices collapsed in 2008-09, during a period of very low, and falling, interest rates.

The response might be that, holding business cycle conditions constant, low rates tend to trigger bubbles. In 2009 the recession overwhelmed the effects of low rates. OK, but asset prices should reflect fundamentals. Interest rates are one of the fundamental factors that ought to be reflected in asset prices. When rates are low, holding the expected future stream of profits constant, asset prices should be high. Bubbles are usually defined as a period when asset prices exceed their fundamental value. If asset prices accurately reflect the fact that rates are low, then that’s obviously not a bubble.

The response might be that “yes asset prices often fall when rates crash, like 2009, and yes asset prices should be higher, ceteris paribus, when rates are low, but the real problem is when interest rates are held at an artificially low level.”

It’s not clear what people mean when they talk of “artificially” low interest rates. The government doesn’t put a legal cap on rates in the private markets, in the way that the city of New York caps rents. The rates are market determined.

At this point people usually respond that governments are a big player in the markets, the Fed buys lots of bonds. OK, but how would we know if the rate is in some sense “too low?” As far as I know the most popular theories all derive from Wicksell’s notion of a natural interest rate and an actual interest rate. The natural rate was the rate that led to price stability (or 2% inflation in the modern context.) An excessively low interest rate was an interest rate that led to excessive inflation. In the US, inflation is currently running below 2%. Although it is above 2% in the UK, many bubble proponents believe the rate of NGDP growth (and by implication inflation) should be still higher, and hence that interest rates are still too high. So we don’t have artificially low rates in the Wicksellian sense in the US, and probably not in Britain.

The most recent iteration of this argument has less to do with bubbles than with the relative efficiency of a market system vs. a centrally planned economy. Thus one argument is that when interest rates are very low, perhaps for justifiable reasons related to a very weak economy, firms will take advantage of those low rates and wastefully misallocate resources. In that case it might be better to have central planners allocate capital. This is the argument that led Matt Yglesias to call Larry Summers a “socialist.” I’m not going to call anyone a “socialist” as it reminds me of when foolish young bloggers call conservatives “racists,” but I will say that some of the tweets in the twitter discussion remind me a bit of Summers’ comments.

I can’t really comment on the claim that the private sector will misallocate resources when rates are low but the public sector won’t (as often), because I don’t know the model that’s being relied upon for those claims. It just seems like a sort of free flowing assertion pulled out of the air. When the proponents of this argument come up with a model (not necessarily mathematical, a verbal model is fine) then I’ll have something to argue against. Until then I’ll favor a monetary policy that leads to stable growth in nominal spending, as the lesser of evils.

BTW, One implication of the “low rates causes undesirable bubbles” theory is that replacing easy money with massive fiscal stimulus would raise interest rates above zero. I wonder how the proponents account for the fact that large Japanese budget deficits failed to raise interest rates above zero, but did succeed in pushing the national debt up to more than 200% of GDP. And of course the Japanese government massively misallocated resources into a historically unprecedented set of infrastructure boondoggles, which dwarf anything going on in China. And despite all of that, NGDP in Japan is lower than 20 years, ago, which must be some sort of record.

Tags:

8. August 2013 at 07:38

What does it mean to ‘rely on monetary policy for growth’?

That’s like lamenting that we rely on heart rate policy for life.

Why is NGDP $16 Tril and not $16 or $16 Mil? They forget that all this green paper isn’t a naturally arising commodity.

8. August 2013 at 07:40

Aren’t long term rates at least partially a function of short term rates? And aren’t short term rates controlled by the Fed? If that is true then long rates are not completely market determined. As for inflation, are consumer prices the only prices that matter? If inflation measurements are just another way of looking at the value of the dollar, should we just ignore all the other ways of measuring the value of the dollar? From 2002 to 2008 the Dollar index went down almost 40% while the CPI was well behaved. Did we have high inflation or not? Which measure should we believe? During the same period, the CRB index moved from around 180 to 460 but the CPI was well behaved. Which measure should we believe? What about gold from $250 to $1000? Was that inflation? A bubble? What do we call it?

I don’t like the term bubble as I think people are reacting rationally to the signals the market is sending. But if the signals are distorted by monetary policy what seems rational today may look entirely foolish tomorrow. If you are only looking at one measure of the value of the dollar, you are going to miss a lot of information.

8. August 2013 at 08:26

I think it is an easier argument to make (at least to an economist or someone who understands monetary policy)that rapid changes in the money supply create financial volatility.

But, as has been argued here many times, the level of interests rates is a poor proxy for the status of monetary policy or the rate of growth in the money supply.

I have little doubt that the money created by QE is lifting financial markets. But should that concern me? Only if the Fed cuts off the crack too abruptly. But as long as Benji keeps hooking us up, lets fly.

8. August 2013 at 08:36

I think there is something to this argument, even if ‘bubbles’ is not the best way to talk about it. As you say, lower rates justify higher prices for assets. But it also means that those assets are more difficult to price because when an asset is being priced at 20-30x annual earnings instead of 10x annual earnings, the long term forecast for those earnings is a much more important factor in the valuation. Not to mention the long term forecast for interest rates. A world of low rates is thus a world of substantial financial volatility , even if the prices at all times reflect the best public (and perhaps private) information, since long term earnings forecasts are mostly highly unreliable. To me, this is a distinct disadvantage of a low rate environment because it is basically introducing a lot of extra risk into most investments. Is there something wrong with this story?

8. August 2013 at 09:05

Prof. Sumner,

You might find Noah Smith’s latest post interesting:

“Conservative economic arguments since the crisis: A review”

http://noahpinionblog.blogspot.com/2013/08/conservative-economic-arguments-since.html

8. August 2013 at 09:46

Prof. Sumner,

This one by Krugman is also interesting:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/08/08/what-janet-yellen-and-everyone-else-got-wrong

Krugman asks “Why didn’t the economy come roaring back after 2009” and answers:

“The best explanation, I think, lies in the debt overhang. For the most part, even those who correctly diagnosed a housing bubble failed to notice or at least to acknowledge the importance of the sharp rise in household debt that accompanied the bubble.”

8. August 2013 at 09:47

I wonder how the proponents account for the fact that large Japanese budget deficits failed to raise interest rates above zero, but did succeed in pushing the national debt up to more than 200% of GDP.

More evidence that fiscal expansion doesn’t drive non-gov’t economic growth?

8. August 2013 at 09:54

Wow.

This is extreme and willful bullshit.

You intentionally have cause and consequence backwards, and you willfully once again ignore the causal mechanism behind the causal argument,

This isn’t an accident.

This is a massive reveal of a lack of character and even the most primitive scholarly ethics.

I’m no longer shocked by this among academics.

I watched my professor of moral philosphy steal and then explain he wouldn’t be caught.

What you are doing here Scott is out an out in the open intellectiual crime, — a blatant and patent act of dishonesty and deception — and it’s appalling to witness.

8. August 2013 at 09:58

“The natural rate was the rate that led to price stability…”

I think it more accurate to say it is the rate that balances planned savings and planned investment.

8. August 2013 at 10:01

Scott, you MUST be familiar with George Selgin’s work on the productivity norm.

And it’s been more than 70 years since Hayek corrected and improved Wicksell — eliminating core mistakes in Wicksell eg productivity and capital and the price level, etc.

To be ignorant of these developments is utterly inexcusable, particularly for a historian of 1930s macroeconomic history and theory.

8. August 2013 at 10:06

Hayek showed that a rate of interest leading to economic coordination across time was NOT compatible with ‘price stability’.

Your incompetent is this area is staggering — and the conceit that you came come from such a place of massive incompetence in a domain of science and pronounce it all ‘bad science’ is beyond appalling and straight out unscientific / antiscientific ethics and behavior.

8. August 2013 at 10:17

Justin, I could see someone making that argument if the economy were overheating. But . . .

Joe, Short term rates are just as “market determined” as long rates. It’s just that the Fed is part of the market. BTW, The Fed cannot target even short term rates in the long run, or else the price level explodes. (Excluding the zero bound.)

I agree that the CPI is a poor measure of whether monetary policy is too expansionary, and for the same reason other indicators such as gold prices or exchange rates are even worse. I prefer NGDP.

mpowell, If substantial financial volatility is a result of low rates, and if the low rates accurately reflect credit market conditions, then substantial financial volatility is a good thing. I can’t imagine how financial volatility would be harmful; we want asset prices to constantly be responding to new information, and moving to the position the market thinks is appropriate.

Thanks Travis, I’ll take a look. And Krugman’s wrong, it was tight money that prevented a rapid recovery.

Gene, Is that your view or Wicksell’s?

Greg, And a good day to you too.

8. August 2013 at 10:25

Please for ONCE in your life address the causal mechansim powering position of only pretend to engage — and stop being so scientifically unethical.

It’s unethical, eg to never spend a moment mastering Darwinian biology, and then constantly using your authority to trash Darwinian science with incompetent arguments which are pathetic and idiotic to anyone who IS competent in Darwinian theory.

That is what you have been doing for years with Hayekian macroeconomics — attacking it like a creationist attacking a Darwinian understanding of things from the perspective of someone utterly incompete in the basic mechanics of the Darwinian theory, That is you to a ‘T’ — constantly exposing your complete ignorance of the Hayekian causal mechansim, and trash the Hayekian understanding of things CEO,a perspective of complete incompetence in casual mechansim at issue,

It’s completely unethical, and an attack in the whole spirit of science and ethic which makes science possible.

8. August 2013 at 10:27

Please for ONCE in your life address the causal mechansim powering position you only pretend to engage.

8. August 2013 at 10:32

And there’s the remarkable “bubble” that Japanese assets have been in for the twenty years of low rates. Nice post.

8. August 2013 at 10:59

Excellent blogging. The Fed does not blow bubbles. The private sector does. It is the nature of man. And Wall Street. You can blame the bartender for drunks…

8. August 2013 at 11:32

Duncan Weldon brings up an interesting paper by Phillippe Aghion claiming to show that countercyclical fiscal and monetary policy have different effects on long-run growth. I’m highly skeptical but I’ll reserve any comments until after I’ve had a chance to read it.

I was recently rehashing the research supporting the channels of the monetary transmission mechanism (MTM) and came across an interesting paper that was discussed in the following paper by Mishkin:

http://www.nber.org/papers/w5464.pdf

The Channels of Monetary Transmission: Lessons for Monetary Policy

Frederic S. Mishkin

May 1996

Page 12:

“A related mechanism involving adverse selection through which expansionary monetary policy that lowers interest rates can stimulate aggregate demand invoves the credit rationing phenomenon. As demonstrated by Stiglitz and Weiss (1981), credit rationing occurs in cases where borrowers are denied loans even when they are unwilling to pay a higher interest rate. This is because individuals and firms are with the riskiest investment projects are exactly the ones who are willing to pay the highest interest rate since, if the the high-risk investment succeeds, they will be the primary beneficiaries. Thus, higher interest rates increase the adverse selection problem and lower interest rates reduce it. When expansionary monetary policy lowers interest rates, less risk-prone borrowers are a higher fraction of those demanding loans and thus lenders are more willing to lend, raising both investment and output.”

The paper referenced is “Credit Rationing in Markets with Imperfect Information” by Joseph E. Stiglitz and Andrew Weiss (June 1981).

This gives a mechanism for why bubbles may be more common at the zero lower bound.

Credit rationing means that higher interest rates leads to riskier investment. Thus it’s not the fact that interest rates are too low which is causing bubbles, it is the fact that they are too high. As Britmouse observes in the Twitter thread, low nominal rates are “too high for macro targets”.

Or to state this as provocatively as possible, an implication of the Stiglitz and Weiss credit rationing model is that *high rates cause bubbles*.

8. August 2013 at 11:58

Greg Ransom,

You’re a fool,

Scott’s an ADMIRER of hayek

8. August 2013 at 12:38

benjamin cole –

“Excellent blogging. The Fed does not blow bubbles. The private sector does. It is the nature of man. And Wall Street.”

>> If the private sector blows bubbles, but not the Fed, then are you suggesting Fed monetary policy has no causal relationship with private sector behavior? Or just none when the private sector is blowing bubbles? I agree that there will always be individuals who will buy at highs and sell at lows, i.e. asset price swings that could form bubbles regardless if there’s a Fed, but I don’t see how the Fed can be excused of all culpability.

“You can blame the bartender for drunks…”

>> I asume you mean “can’t?” I recall you or someone else using this same analogy and I don’t think it’s entirely accurate in the context of your comment. A more accurate one is if the bartender is increasing/decreasing the amount of alcohol in each drink and the impact it has on individuals’ drinking patterns and outcomes. For example, 5 people come into a bar and order vodka and clubs. They know from past vodka/club drinking approximately how many will get them to feel a certain level of drunkenness. The bartender decides to dilute the drinks with more club soda and using less vodka and even preannounces it to everyone. Does the bartender share in any culpability if some overindulge by overcompensating for the diluted drinks?

8. August 2013 at 13:03

WOW,

Rand Paul is asked who should be Fed chairman and his answer is……Milton Friedman!

http://nymag.com/daily/intelligencer/2013/08/rand-paul-not-so-good-with-numbers.html

You have got to be kidding me.

8. August 2013 at 13:11

TravisV,

He presumably didn’t mean David Friedman, who is still alive, but a bit too much of a capitalist for someone like Rand Paul.

8. August 2013 at 14:17

If there is a prolonged period of rising incomes are not asset prices going to rise? Not merely from expectations of future incomes but such magnified by savings pushing on investment (to use Andy Harless’s expression).

If there is technological change, are not asset booms and busts more likely, from the uncertainty about the technology?

These things happened in gold standard C19th Britain, after all. Not exactly an “easy money” economy.

And do not supply restrictions magnify the price effects of increased demand? Krugman’s excellent Zoned Zone point about housing prices. And if expectations of increased income increased asset prices why would not expectations of increased value (as in store of)? As per gold or approved-for-housing land.

In a market economy with multiple interest rates and multiple assets, with assets being various levels of income-expectation, value-expectation, and expected risks, how can one measily central bank rate be more important than any of the above?

And, in a market economy with multiple interest rates and multiple assets, with assets being various levels of income-expectation, value-expectation, and expected risks, how can one interest rate be “the” rate that balances planned savings and planned investment?

(And is such a malinvestment story compatible with any level of rational expectations?)

8. August 2013 at 14:34

I should add that I think of the role of the central bank rate in monetary policy not as a mechanical policy lever but as a signalling device whose effect depends upon the policy framework in which it is embedded.

(And I remain puzzled by all that commentary which apparently thinks that expectations about inflation count but about incomes don’t or are somehow subordinate to the former. Such as talking about “debt overhangs” independent of income expectations.)

8. August 2013 at 15:06

W. Peden,

You have a lot of very interesting things to say. Do you have a blog? If so, I’d love to subscribe to it.

8. August 2013 at 15:09

TravisV,

No, but it’s on my “To Do” list for 2013.

8. August 2013 at 15:14

Wow,

Krugman continues to urinate all over Milton Friedman’s grave:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/08/08/milton-friedman-unperson

He’s practically saying “Nanny-nanny boo-boo” to Market Monetarists.

8. August 2013 at 15:20

Krugman’s post is actually echoing a lot of what Yglesias wrote back in July 2012:

http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2012/07/31/milton_friedman_and_his_legacy.html

“Friedman’s way of putting this has created two problems. One is that on the right a lot of folks view calls for central banks to adopt appropriate monetary policy as just another form of government activism. Meanwhile on the left thanks to co-branding between a monetary focused view of macroeconomic policy and Friedman’s views on other matters, many view it as a kind of sellout to argue that business cycle problems can be cured with monetary policy.

So we’re left with a world in which Friedman is an iconic figure, and yet no major political movement in any of the developed world’s major countries is calling for a Friedmanite solution to the dominant policy problem of the moment.”

8. August 2013 at 15:35

TravisV,

He’s right about one thing: people these days talk a lot about Hayek and Keynes, and not about Friedman. And that’s a big part of the problem.

8. August 2013 at 15:45

Here’s a question related to Friedman:

Could someone list out the economists who said AT THE TIME in the early 1970’s that money was too easy and said AT THE TIME in the mid-1990’s that money in Japan was too tight?

To me, Friedman’s ability to identify both of those facts so early is enormously impressive. If there’s anyone else in existence who accomplished that feat, he deserves more attention.

8. August 2013 at 16:18

and then

In the US, inflation is currently running below 2%. Although it is above 2% in the UK, many bubble proponents believe the rate of NGDP growth (and by implication inflation) should be still higher, and hence that interest rates are still too high. So we don’t have artificially low rates in the Wicksellian sense in the US, and probably not in Britain.

I can’t be the only one who noticed how the first quote contradicts the second quote.

First we’re told not to reason from a price change, but then we’re told that interest rates are not artificially low, on the basis of…what for it…reasoning from a price change (price level change, i.e. inflation).

———————-

We can know if the given rate is too low, by reasoning from individual subjective preferences constrained to the market, i.e. to private property rights. More specifically, we can infer from the fact that the Fed has to “do something” in order to change the future. Thus, given the Fed is “doing something”, we can then know that the free market process, that is, a process without initiations of coercion in the general price system, that is, a world without a monopoly banking system backed by political force, would have led to different outcomes.

After all, if the outcomes with a Fed were equal to the outcomes without a Fed, then not only would there be no reason for having a Fed, not only would it imply that everyone who thinks the Fed affects the economy are wrong, but it would mean everyone who controls the Fed are wasting their time. But given that they are constantly choosing to use the Fed system, to their benefit, it proves that the outcomes are indeed different.

So we know that the outcomes are indeed different. But how can we know if the difference is such that we can say interest rates are “artificially low”, instead of “artificially high”? Here, we need an additional knowledge. We can infer from the fact that in order for the Fed to raise the fed funds rate, it has to reduce the amount by which they increase bank reserves, and in order to for the Fed to lower the fed funds rate, it has to increase the amount by which they increase bank reserves.

These concepts “reduce the rate of increase” and “increase the rate of increase” are defined by how they compare to individual subjective preferences constrained to private property rights, i.e. what a free market process in money would have generated.

The standard metric of comparison is the collection of individual (subjective) valuations in the market, NOT measurable dollar based statistics.

It shouldn’t take many brain cells to look at the quantity of loans that have been issued by the Federal Reserve Cartel and estimate that they are almost certainly greater, much greater, nay, much much much greater, than what would have otherwise transpired in a free market in money.

With that many more loans issued, we can then know that the rates, since they have to fall in order for more to be accepted by borrowers, are lower than what otherwise would have transpired in a free market. In other words, and finally, we can say that “interest rates are artificially low.”

————————

So why would artificially low interest rates generate bubbles, booms and busts? It has to do with the temporal nature of capital investment. Individual investors allocate resources not only in cross sectional terms, such as which industry to invest in, but also in terms of how long in the future the final product is intended to be ready for consumption. It is this latter concept of the capital structure of the economy that is utterly lost on macro-economists who utilize equilibrium analyses. NGDPLT, that’s equilibrium. Price inflation targeting, that’s equilibrium.

So when the Fed System brings about artificially low interest rates, the meaning of which we all hopefully now have a better understanding, what they are doing are misleading investors into allocating capital into projects that are legitimately profitable, but cannot be completed in the physical sense because the real capital necessary to complete those projects is not available.

As the capital structure becomes more and more stressed, the central bank finds itself having to drastically increase the money supply in order to delay, not eliminate, the necessary rebalancing corrections that the market process is constantly trying to bring about (which is why the Fed has to keep inflating day after day in order to prevent immediate correction (recession)!).

In short, the Fed has to keep acting in order to change the economy because the market process keeps counteracting it whereby market actors want to change the economy another way.

It’s hard for socialist minded dictator wannabes, like monetarists, to accept the fact that recessions are a sign that individuals want to change the economy in a way different from what the central bank wants. The reason it is hard is because they intellectually align themselves with the Fed, not the market. They rationalize this with various “necessary evil” excuses, and so on, but at the end of the day, they don’t want the market corrections to occur. That makes them anti-market socialists by implication. I’m not afraid to call a socialist a socialist. I don’t consider 1984 a manual, I consider it a warning.

I would love for just one critic of the malinvestment theory on this blog to show that they understand it. I have not yet seen anyone show that they do. It’s always, ALWAYS, anti-intellectual pejoratives, hand wavings, insults, dismissals, and arrogant posturing. It’s almost as if the fear felt in actually engaging the theory is somehow evidence that there is something wrong with it. Remember what Yoda said about fear.

8. August 2013 at 16:23

Never reason from a spending change.

Interest rates were, and are, above zero.

Central banking ALSO brings about “massively misallocated resources”. It does so by deluding investors and consumers into acting as if there is more real capital than really exists.

8. August 2013 at 16:27

Never reason from a spending change.

Interest rates were, and are, above zero.

Central banking ALSO brings about “massively misallocated resources”.. It does so by deluding investors and consumers into acting as if there is more real capital than really exists.

8. August 2013 at 16:34

Low discount rates (which may not be quite the same thing as low market interest rates) do make assets hard to value (which may not be quite the same thing as causing bubbles), because they make asset values more sensitive to flows in the more distant future, which are harder to estimate. For example, if you assume a constant growth rate, as asset value is V = d/(r-g), where d is the current flow (“dividend”), g is the growth rate, and r is the discount rate. If r is only slightly higher than g, then a slight change in g will have a dramatic effect on V. So suppose r is low, and people happen to get a little too optimistic about g. It’s debatable whether this fits the definition of a bubble, but in any case it’s going to cause the price of the asset to skyrocket, and when the overoptimism fades, the asset price will collapse. (Of course the situation is symmetric. Maybe people rightly became optimistic about g, the asset price rightly skyrocketed, and then people happened, wrongly, to get just a little bit less optimistic, and the asset price collapsed. In this case there wasn’t a bubble per se, but the same volatility problem exists.)

8. August 2013 at 16:52

I you believe that low rates do not cause bubbles, then may I ask what your response is to David Beckworth’s posts?

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.kr/2010/09/what-role-did-fed-play-in-housing.html

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.kr/2010/01/bernanke-goes-for-ko-and-misses.html

8. August 2013 at 17:41

Greg, I suppose the most amusing thing about your comment is that you seem to think this post is attacking Austrians, whereas all the people I cite above appear to be either market monetarists or Keynesians.

But I suppose if your whole reason for existence revolves around protecting Hayek’s reputation, then you’d think anyone who mentions misallocation must be attacking Hayek, even if the argument is linked to Larry Summers.

Britmouse, Very good point.

Mark, I suppose the bigger problem here is that most people who complain about “low rates” think it is caused by easy money, and that tighter money would raise rates, whereas just the opposite is more likely, at least in the long run. So even if low rates caused bubbles, the correct policy response would be more monetary stimulus.

Mike, If the Fed was causing low rates with easy money, we’d have high inflation/NGDP growth. Since we don’t have high inflation/NGDP growth, it’s a moot point as to whether low rates cause bubbles. Even if they did, it wouldn’t be due to easy money.

Lorenzo, Good points.

W. Peden. Oh no! Not another blog that I have to read!

Travis, Krugman knows nothing about monetary history. It’s embarrassing to read the stuff he writes on that subject. And unlike many conservatives I think his macro stuff is often excellent. But not monetary history. The piece he wrote after Friedman died was a disgrace.

Andy, Yes, asset prices might be more volatile, but that would not be because of monetary policy in any case. At least not for any extended period of time. Suppose rates were low, but inflation was below target. The Fed could raise rates, but that would drive inflation even lower. In that case either rates would fall again, or we’d go into deflation, and rates would fall a bit later.

In any case, I see asset price volatility as being very different from asset price bubbles. Japanese stock prices have been very volatile over the past 20 years, but there has been no Japanese stock bubbles over the last 20 years. So it’s not clear that this sort of asset price volatility is a problem.

8. August 2013 at 17:44

John, I disagree with the claim that low rates contributed to the 2006 housing bubble, at least in a major way. I agree that expansionary Fed policy did contribute, but I think David overstates the importance. I’d say it was 5% easy money, and 95% bad banking regulation (combined with private sector mistakes.)

8. August 2013 at 22:31

Mike T:

I don’t if you are still reading, but I enjoyed your comments, and so here goes…

1. Before there were even central banks, there were booms and busts (in fact perhaps more so). Was the 1990s equities boom caused by the Fed? Or a very good and compelling story put together by Wall Street? I think the latter—and indeed, some equity .com plays did work out. The Internet was huge…it was just hard to pick the winners. There were mostly losers. Did the Fed make investors so hung ho?

The 2000s property boom: there were sophisticated institutional investors paying more-than-top top dollar for trophy real estate. They were deluded by…Fed policy? No, I think there was good case to be made that some properties would be valuable for a long time, and throw off good rents. And there was a glut of institutional money seeking a home. They overpaid, with open eyes and of their own free will. Actually, many of those properties are coming back, so the fundamentals were not rotten.

As for my bartender: What I mean is that the Fed is a bartender, and he serves the drinks. If people get drunk on a market, it is because they chose to imbibe too much. It is irresponsible for investors to say “Well, the Fed made me do it.”

Really? The Fed makes investors overpays for assets? And should Mommy Fed decide when investors are overpaying, and clamp down on that?

I fear if the Fed, already an independent institution that badly wants away from the dual mandate, is then also given a mandate to “prevent bubbles” that we will become Japan No. 2. That’s No. 2 in the duplicative sense and in the toilet sense.

The Fed will have its genteel wing-tips right on the throat of the US economy at all times, cutting off the monetary air supply.

9. August 2013 at 01:11

Scott, in the history of ideas it is not unusual for people to target the pretenders, the pip-squeek bandwagon jumpers, and the hangers-on rather than the mega-tonnage cargo liner rocking and drafting all of the little rafts,

So you have people launching arguments against the vague musings of ‘evolutionists’ aping Darwin’s evolutionary language as a hand-waving metaphor, but utterly lacking the Darwian causal mechansim that makes either whole thing go. In these instances Darein is never engaged, and hence the causal explanatory science of evolution is never engaged.

Tilting at the windmills of cheap, undeveloped cardboard & styrofoam makeshifts is merely pretending that one is engaging the deep channel of the principle explanatory current addressing interest rates and the coordination and misvaluation of production goods.

The pretense that you were engaging the deep current was made plain by your reference to Wicksell and the relation of the natural rate and the price level.

But rather than establishing engagement with the serious causal mechanism, this simply showed that you weren’t engaging the deep current, you were engaging an confused and flawed precursor, sort of like engaging Erasmus Darwin or Lamarck with the pretense that your are engaging the mechansim of Charles Darwin.

9. August 2013 at 01:30

Your pretense, Scott, is that by flicking away these little gnats — and the big gnat Wicksell — you’ve adressed and disposed of the explanatory program in macroeconomic science relating interest rates to coordination and discoordination through the network and structure of production processes.

Well, that pretense is a simple fraud — because you’ve pretended to address the causal mechansim when you’ve not even acknowledge the existence of the mechansim itself, which wasn’t worked out by these gnats, but was worked out by Hayek.

Again, it’s like flicking away all sorts of forgotten ‘evolutionists’ — and pretending you’ve addressed and disposed of Charles Darwin and the mechanism of the evolution of adaptive traits and species by natural selection.

9. August 2013 at 04:14

George Kerevan, economics correspondent for the Scotsman newspaper, comes out in favour of NGDP targeting-

http://www.scotsman.com/news/george-kerevan-central-bankers-and-politics-1-3037233

“I distrust Carney’s new unemployment target, which I think plays to a political agenda. I’d prefer the Bank to target nominal GDP (ie growth uncorrected for the rate of inflation). If nominal GDP growth is faster than average it indicates inflation, so you raise interest rates. If nominal GDP is slower than average it indicates recession, so you cut rates. That way you combine a sensible growth target with keeping tabs on inflation.”

It wasn’t so long ago that he was (a) calling for tighter monetary policy to reduce inflation and (b) looser fiscal policy to boost growth. I like to think that my letter at least got him thinking about why that way of thinking is mistaken. I could have never expected that he’d come around to NGDP targeting so quickly; now the challenge is to get the rest of journalistic opinion in Britain on side…

9. August 2013 at 05:19

Geoff-

“It shouldn’t take many brain cells to look at the quantity of loans that have been issued by the Federal Reserve Cartel and estimate that they are almost certainly greater, much greater, nay, much much much greater, than what would have otherwise transpired in a free market in money.”

While your conclusion seems reasonable, your most important argument – by far the most important idea in your entire post – relies on “it shouldn’t take many brain cells to…”

A few thoughts on the most important constraints on the monetary policy of GoogleDollars or whatever we would be using if the Fed didn’t exist would go a long way.

9. August 2013 at 05:51

Greg, You said;

“Tilting at the windmills of cheap, undeveloped cardboard & styrofoam makeshifts is merely pretending that one is engaging the deep channel of the principle explanatory current addressing interest rates and the coordination and misvaluation of production goods.”

I’m confused, does that mean I should ignore your comments?

Thanks for the tip W. Peden.

9. August 2013 at 06:06

I have to say that I count myself among those dismayed by this post, Scott. You fail to give those who worry about monetary policy causing bubbles credit for understanding, no less than you do, the fact that whether M-policy is excessively easy or not isn’t the absolute level of interest rates, but one concerning the relationship between that level and the “natural” rate of interest.

For this reason the fact that l.ow rates in 2008-9 didn’t promote a bubble is perfectly besides the point, because at that time interest rates, though very low, were presumably high relative to the natural rate. But no such presumption can apply to conditions in 2003-6, when on the contrary a large body of evidence suggests that actual rate were below their natural counterparts.

Market Monetarists have a right to object to those more naive Austrians who refuse to recognize the possibility of a monetary shortage, as well as to scold economists of all schools who just as naively assume that low rates cannot be associated with tight money. But they deserve to be scolded themselves when they flip the errors of those they criticize on their heads. There are, in fact, good grounds for suspecting that every major modern episode of a severe monetary shortage of the sort MMs are most anxious to have central banks combat came about in the wake of the bursting of a bubble that was itself at least to some extent the consequences of monetary policy errors in the opposite direction.

It has always struck me as bizarre that monetary economists should tend to be divided among two camps, those who worry only about excessively tight money and dismiss arguments about the dangers of easy money, and those who do just the opposite. Of course, Scott, I don’t mean that you are generally inclined to write as if belonging to the first group. But in this particular post I fear that you do come across rather as if you did.

You also write: “Andy, Yes, asset prices might be more volatile, but that would not be because of monetary policy in any case. At least not for any extended period of time. Suppose rates were low, but inflation was below target. The Fed could raise rates, but that would drive inflation even lower. In that case either rates would fall again, or we’d go into deflation, and rates would fall a bit later.” Well, there goes the whole understanding of the distinction between productivity-based changes in inflation and the kind link to changes in NGDP, and with it the whole reason for NOT wanting the Fed to stick to targeting inflation. If inflation is “below target” because of above-average productivity growth, then the “target” ought to be lowered, which means raising rates, other things equal. Doing that doesn’t cause a deflationary spiral, because it is merely sticking to the path of the natural rate of interest. Here again, you seem to argue inconsistently, favoring NGDP targeting over inflation targeting when the former would be less dis-inflationary, but not when it would be more dis-inflationary. (Note that this isn’t a “productivity norm” argument, for I make no assumption about what the long-run trend rate of NGDP growth should be.)

Finally, interest rates are relative prices. Of course to the extent that the fed can influence them, by driving a wedge between their actual and natural levels, it doesn’t merely influence the rate of change of general prices. It also influences asset prices differentially, and therefore create self-reversing asset price changes, though by how much is an empirical question depending on many factors, including the extent to which policy influences longer term as opposed to merely short term rates. But to suppose that there is no differential asset price influence of easy monetary policy is surely unwarranted.

9. August 2013 at 07:09

Memories can be short, can’t they;

http://press.princeton.edu/titles/978.html

‘”Friedman argued that the best way to make sense of saving and spending was not, as Keynes had done, to resort to loose psychological theorizing, but rather to think of individuals as making rational plans about how to spend their wealth over their lifetimes. This wasn’t necessarily an anti-Keynesian idea–in fact, the great Keynesian economist Franco Modigliani simultaneously and independently made a similar case, with even more care in thinking about rational behavior, in work with Albert Ando. But it did mark a return to classical ways of thinking–and it worked. The details are a bit technical, but Friedman’s ‘permanent income hypothesis’ and the Ando-Modigliani ‘life cycle model’ resolved several apparent paradoxes about the relationship between income and spending, and remain the foundations of how economists think about spending and saving to this day.”–Paul Krugman, New York Times’

9. August 2013 at 07:13

George Selgin

“For this reason the fact that l.ow rates in 2008-9 didn’t promote a bubble is perfectly besides the point, because at that time interest rates, though very low, were presumably high relative to the natural rate. But no such presumption can apply to conditions in 2003-6, when on the contrary a large body of evidence suggests that actual rate were below their natural counterparts.”

Maybe not:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/04/02/was-monetary-policy-easy-in-2003-2004-not-according-to-robert-hetzel/

9. August 2013 at 07:52

Marcus, Hetzel writes, “Most important, inflation of about 2% measured by the core PCE deflator remained close to the FOMC’s implicit inflation target (Hetzel 2008b, Ch. 20). The inflation numbers are impossible to reconcile with the assumption of an expansionary and ultimately inflationary monetary policy.

With all due respect, this is the sort of argument that utterly ignores the whole point about why inflation targeting isn’t reliable. The period was one (according to most estimates, including those being relied upon by the Fed) of a productivity surge. Sound policy called for a lower inflation target to reflect that surge. Hetzel, like most old-fashioned monetarists, doesn’t get this. Those who profess to understand the advantages of NGDP targeting ought to get it. In appearing to accept Hetzel’s view you merely demonstrate the very sort of inconsistent thinking about NGDP versus inflation targeting for which I take Scott to task in my original comment.

9. August 2013 at 08:12

Scott, I don’t know how you can so easily dismiss volatility in financial assets. People are pretty much always willing to pay for lower volatility so I think it should be pretty obvious that volatility is undesirable. Anyone trying to invest their savings for retirement would surely appreciate this point. And sure, it’s better that prices reflect update market prices than not, but that wouldn’t reduce medium to long term volatility and that’s really not what we’re talking about. The issue is the lower rate of natural interest. Is this a good thing or a bad thing? Well, one good thing about it is that it encourages capital investment. One bad thing is that it leads to asset price volatility. Then the follow up question is okay, does our combined monetary/financial policy have any impact on the rate of interest that is associated with price stability? I have seen a lot of economists argue that lower deficits with appropriate monetary offset lead to a lower rate of interest that results in price stability. This is one of the theories behind the economic expansion of the 90s. You can argue that this theory doesn’t make sense – that the natural rate of interest is determined exogenously and that the difference between the actual interest rate and natural rate of interest that leads to stable policy is not impacted by federal deficits (though this is a quite common implicit assumption in a wide variety argument regarding deficits), or you can argue that on balance low rates of interest are desirable because the positive impacts outweigh the negative. But I don’t see how you can argue that asset price volatility by itself is a good thing. The market quite clearly assigns a negative value to volatility if you believe in efficient markets, surely this must reflect underlying preferences/utility?

9. August 2013 at 08:32

[…] I’d say there is some truth in this, but it’s becoming less true every day, as more and more conservatives jump on the market monetarist bandwagon. (Larry Kudlow is one of the recent converts, but there are many others.) I see enormous interest in MM, growing almost every day. Just yesterday W. Peden left this comment: […]

9. August 2013 at 09:01

George, I’m afraid you misread my post in a number of ways. Nothing in my post was directed at Austrians. That target was Keynesians who worry that low rates will create bubbles, and who favor fiscal stimulus for that exact reason. It was directed at the tweets above (from people I took to be Keynesians), and some Larry Summers comments

I am quite certain that you are not in the camp of people favor fiscal stimulus, and hence nothing in the post was directed at your views of monetary economics.

I’ve also tried to be completely consistent in my views on NGDP growth. When it was much too high I said it was much too high. And when it’s been much too low I’ve said it’s been much too low. So I don’t see any inconsistency. Perhaps this misconception comes from my preference for thinking in terms of level targeting. Under level targeting the optimal rate of NGDP growth is not constant, but rather the rate that gets you back to the trend line. If the Fed is not doing NGDP targeting, then the trend line is highly subjective. That’s where I disagree (slightly) with David Beckworth. I’m inclined to think monetary policy was OK in 2003-04 despite fairly fast NGDP growth, because it was recovering to trend. In 2005-06 it was a bit too high, but that error was tiny compared to the error of 2008-09. So I don’t see any asymmetry.

As you know, I don’t believe asset price bubbles exist. I believe that markets price assets rationally given market conditions, which include nominal interest rates. When easy money is a problem you get costly distortions to the labor market, but asset markets continue to price assets rationally. The distortion to the labor market causes excessive work effort and excessive output, and that’s caused by too much NGDP, not low rates. That’s where the harm comes from, a distorted labor market. And of course it’s unsustainable, so it’s often followed by a relapse into recession, where the harm is more noticeable.

I don’t believe that rates are low because money is easy, which is the assumption of the people (like Summers) that I criticize. Because of that I don’t believe tighter money can help us get away from low rates, because I believe tighter money would (over time) push rates still lower, as in Japan and Europe.

Even if monetary policy does cause asset price volatility, as we saw in 1987 and 1994, asset price volatility is not necessarily a problem. Where it is (say in housing) it’s due to specific defects in housing regulation. Obviously you’d want monetary policy to avoid exacerbating those defects, but you don’t do that by getting rid of low rates, you do that by avoiding NGDP volatility.

You said:

“For this reason the fact that low rates in 2008-9 didn’t promote a bubble is perfectly besides the point, because at that time interest rates, though very low, were presumably high relative to the natural rate. But no such presumption can apply to conditions in 2003-6, when on the contrary a large body of evidence suggests that actual rate were below their natural counterparts.”

This is 100% consistent with what I said in the post. I mentioned that rates were low because of the weak economy, and what really matters is the level compared to the Wicksellian equilibrium rate. If they were below that rate in 2003-06 (quite possible) then money was too easy, as you say. None of my post was addressed toward the events of 2003-06, so I don’t see how you can claim I was misleading.

My only regret is talking about inflation being below 2% in the US, when I should have talked about NGDP growth averaging below 2.5% since 2008. But the implications are identical. Perhaps I should stick to my promise to never mention inflation, but in trying to speak to a broader audience I sometimes frame my arguments in terms of inflation. That’s what actual policymakers seem to care about. I suppose that creates the impression of inconsistency, but in substance I think I’m consistent.

9. August 2013 at 09:05

mpowell. Let me use an analogy. A horrible frost destroys 90% of the orange crop. Prices soar. I agree that the higher prices hurt people, but I still see them as optimal. That’s the point I was trying to make.

You could prevent high orange prices with price controls, and you might be able to prevent asset volatility with extremely bad monetary policy (although I have my doubts.) But it’s better to do optimal monetary policy (stable NGDP growth) and let price volatility accurately reflect market uncertainty at the going rate of discounting future profits.

I’m saying asset price volatility is good in exactly the same sense that I believe high orange prices after a frost are “good.”

9. August 2013 at 11:30

Scott, I think I understand your point and I agree with you with respect to your analogy, but that’s not really what I’m talking about. Andy Harless had a comment upstream making the same point I am. In a world of low discount rates, future expected returns heavily influence asset prices. This means that as an investor your expected returns on assets will be more volatile over the same time horizon. You can think of it very simply this way: if I want to purchase a company’s earnings for the next 10 years, I can buy their stock. Then I get the volatility of earnings for the next 10 years. But when I go to sell the stock I also get the volatility of any change in expectation of earnings for many future years and that will impact my returns to a greater degree with a lower discount rate. That’s definitely a downside for the investor, though maybe that’s okay given other benefits of low interest rates.

There is another question as to whether the mix of fiscal plus monetary policy can have any impact on the interest rate. Some people argue that with appropriately offsetting monetary policy, lower federal deficits leads to lower interest rates. This makes sense to me, but the example of Japan suggests otherwise (did they have too much monetary offset?). I am wondering if you have an opinion on this specific question.

9. August 2013 at 13:44

Scott, you write “OK, but asset prices should reflect fundamentals. Interest rates are one of the fundamental factors that ought to be reflected in asset prices. When rates are low, holding the expected future stream of profits constant, asset prices should be high. Bubbles are usually defined as a period when asset prices exceed their fundamental value. If asset prices accurately reflect the fact that rates are low, then that’s obviously not a bubble.”

Ah: here is where we disagree. The usual bubble-fundamentals dichotomy is the culprit, and needs to be scrapped. The question is at hand is, “Can there be _unsustainable_, that is, self-reversing, upward asset price movements as a result of excessively easy money. Whether those answering “Yes” to this question are Keynesians or Austrians isn’t the issue. Nor is th”e issue I’m concerned with whether rates have been “too low in recent years. It’s the general theoretical question that is the issue. The quote from Duncan Weldon suggests that his answer is “yes.” You answer “no.” I believe that Duncan’s answer is the better answer.

Why? Because the problem with the usual fundamentals-versus-bubbles dichotomy is precisely that it excludes the third alternative of asset price movements that are a response to departures of i from i(n). You say, an upward asset price movement in response to a lowering of i is a rational response to a fundamental change, therefore, not a bubble and (here is the non-sequitur) therefore not a problem. Butit is a problem if the decline in i is in fact a reduction of i below i(n) that occurs in consequence of excessively easy money. Why? Because in that case the asset price movement, though technically not a “bubble in the strict sense, is not sustainable: the “non-bubble” is, in other words, bound to pop! Why unsustainable? Because (and here is where Wicksell comes in) the interest rate movement upon which it is based is itself self-reversing. No policy can succeed in holding i below i(n) indefinitely. Not even accelerating inflation, if it came to that. Eventually the demand schedule for nominal loan funds shifts out as much as the supply schedule, at which point it’s “Game Over” for the asset price boom.

Now, it happens that Wicksell screwed-up in assuming that so long as P was stable i must = i(n). That’s not generally correct. In fact it’s NGDP stability that’s needed, or, alternatively, stability of w, understood to represent an index of factor rather than output prices. If productivity grows faster than usual, causing P* to decline _relative to_ w*, you can have an unsustainable asset price movement (let’s agree not to call ikt a “bubble”) despite perfectly stable P* (or dynamic equivalent).

None of this is of course meant to deny that Keynesians may be grasping the “bubble” stick simply as a means to plead for fiscal stimulus. A pox on them for that. But the theoretical question that Weldon’s quote poses is what I took, rightly or wrongly, to be the issue at hand. And that is where our disagreement lies.

9. August 2013 at 15:38

mpowell, Obviously that’s possible but I’d have to know why rates are low before I drew any conclusions about volatility. Rates are endogenous, so although I could imagine scenarios where low rates led to volatility, I could also imagine the opposite.

I doubt whether fiscal policy would have much impact on long term real rates.

George, You said;

“No policy can succeed in holding i below i(n) indefinitely. Not even accelerating inflation, if it came to that. Eventually the demand schedule for nominal loan funds shifts out as much as the supply schedule, at which point it’s “Game Over” for the asset price boom.”

Yes, I agree, but the markets also know this, and it’s factored into asset prices. Indeed it’s factored into long term real interest rates. So if the Fed reduces short term real interest rates to unsustainable levels (obviously they haven’t done so, as NGDP growth is currently quite slow) then markets would expect real rates to rise in the future, and long term real rates would reflect those expectations.

Just to be clear, when I said the higher asset prices are not a problem, I did NOT mean to suggest that the underlying monetary policy that created low rates and higher asset prices is not a problem. That may well be a problem, but only if NGDP growth is excessively fast. That was my point. The excessive NGDP growth is the problem, rates and asset prices being distorted doesn’t make the problem worse, as markets price these things efficiently, given monetary policy. They are an epiphenomenon.

In contrast, labor markets do not respond efficiently to monetary policy shocks.

I agree that Wicksell should have used NGDP, and not P and the benchmark.

9. August 2013 at 18:15

Dr. Sumner:

That section in italics is not correct. The dichotomy between nominal interest rates and natural interest rates arises in an economy introduced with central banking that brings about non-market money outcomes, not an economy introduced with central banking that targets something other than 5% NGDP growth. The dichotomy is present for reasons apart from NGDP growth. In other words, it is not correct to argue that if NGDP growth is “low”, then that somehow means short term interest rates are not unsustainable.

What is correct to argue is that while nominal interest rates are influenced by NGDP growth, the absolute difference between natural rates and nominal rates is greater than zero no matter what NGDP the Fed brings about, other than, of course, the exact historical pattern of interest rates in a free market of money, where natural rates and nominal rates are always identical. I think it is safe to say that free market rates are not identical to those prevailing in an economy with a fixed rate of NGDP growth brought about by a central bank.

Just like “stable prices” is a misleading indicator of whether or not nominal rates are equal to or close to natural rates, so is “stable NGDP” as well. A stable NGDP growth could very well be synonymous with nominal rates being persistently lower than natural rates.

But markets work within a central banking system, not a world with a finite expected lifetime of central banking. Yes, if the market expected the Fed to be abolished in the year 2020 say, then what you said would be correct. But the problem is that investors cannot predict just when the capital structure becomes stressed enough that a recession ensues. Investors chase after profits, they don’t chase after investments that they know are physically sustainable within the context of a world division of labor and sustainable world capital allocation.

Nobody knows what a sustainable real capital structure should look like going forward. As Hayek noted, only the market process itself can reveal the information needed to make but a remotely informed judgment. Unfortunately, the pricing system that prevails in a central banking economy do not convey an accurate enough set of relative profitability signals that are required to reward and punish investors into allocating real capital in something close to a sustainable configuration.

You cannot claim that because NGDP growth is “low”, that this somehow means nominal rates are close to natural rates. Natural rates are a function of the difference between the valuation of present goods over future goods. It is NOT the rate on loans. The rates on loans is but one manifestation of it. Relative profitability signals are a component as equally important as the nominal interest rate structure of loans of varying maturities.

9. August 2013 at 18:17

Scott, I don’t think it can generally be assumed that markets participants “know” when i is not = i(n). The latter is of course unobservable, and even we economists disagree about when or whether rates are at natural levels. I do agree that markets will of course reflect suspicions that i isn’t r(n) when these are widespread.

I’m afraid I must also continue to disagree with your claim that because the market prices assets “efficiently,” in the sense meaning that it prices them according to the information available to it, the distortions in question are “epiphenomena.” This claim simply overlooks the point that the information available to market participants may consist in part of interest-rate information that has been distorted by excessively easy monetary policy. Here again you seem to fall victim of the false “fundamentals-bubble” dichotomy, according to which nothing save “irrational” behavior can lead to unsustainable asset price movements. The fact that i is perfectly flexible doesn’t mean that i always = i(n). Indeed, the “stickiness” of factor prices is itself one of several factors that delay the adjustment of i to i(n). I think, in short, that the way to properly understand Wicksell is to recognize how in the short run, while w remains “sticky,” monetary shocks and the excess demand for m that they give rise to are “handled’ by i movements involving departures from i(n), and that these movements wear out as w (AS schedules, actually), eventually respond to the monetary innovations. So it’s really not correct to imagine that the sluggishness of labor markets is “instead of” asset price distortions.

9. August 2013 at 18:24

No, again you’re reasoning from an NGDP change. Never reason from an NGDP change. It’s as bad as reasoning from a price change, or an interest rate change.

Even if NGDP growth is low, it could very well be associated with a distinct enough difference between nominal rates and natural rates that an unsustainable boom is generated. For example, if an economy switches to a higher trade deficit, whereby more money and spending leave the economy than enter the economy, where domestic NGDP otherwise falls, and foreign NGDP rises, a domestic policy of fixed NGDP growth could very well be associated with a boom generating difference between nominal rates and natural rates.

Never reason from an NGDP change.

Never reason from an NGDP change.

It’s not excessive NGDP growth that is the problem, it’s excessive distortions to economic calculations that are the problem, regardless of what is happening to NGDP.

Markets cannot “efficiently price” price distortions! It would be like saying carpenters can “efficiently measure” the length of their own tape measures that have been bent and twisted, even though the only tools they have to measure their bent and twisted tape measures are their bent and twisted tape measures themselves.

Efficient pricing requires efficient protections of private property rights. Since the money supply is monopolized by the state, private property rights constraints do not apply to money itself, and so money’s use as an “efficient” pricing tool of economic activity is degraded.

9. August 2013 at 18:31

Money prices can communicate information of non-money goods produced in a free market “efficiently” only if money production itself is constrained to the free market process.

While we can all pat ourselves on the backs by appearing as kowtowing bootlickers, excuse me, as pragmatic non-ideologues, by trying to make the best of a bad situation that is central banking, that does not entitle you to pretend to be talking about a free market, nor free market efficiency.

Efficient markets refers to markets, not governmental monopolies such as central banking.

Monetarists have no right to talk about their belief in any efficiency of empirical “markets”. Empirical markets are not markets of which “efficiency” applies.

10. August 2013 at 05:36

George, If someone is going to argue that monetary policy is too expansionary or too contractionary, that will presumably be based on publicly available information. That information set is available to both the central bank and the public. So it’s factored into asset prices. (But not into sticky wages)

Now I agree that a central bank can make a mistake through no fault of its own. The world is a very messy and complex place, and they may misjudge the situation. In that case the markets may make the same error. I’d guess both the Fed and the markets overestimated the sustainable rate of RGDP growth going forward in 2006, for instance. (Which is why they shouldn’t target RGDP growth!)

Here’s where I disagree with many economists. They seem to think that they can see flaws in Fed policy that the markets can’t see. Thus they see an easy money policy in 1929 leading firms to construct the Empire State Building, and these perceptive economists understand that it will all end in a crash and the ESB will end up being a white elephant by 1932, but the businessmen who plan and build the structure don’t see that easy money in 1929 will have that effect. Perhaps I’m misrepresenting the views of others, but that’s the impression I get.

10. August 2013 at 22:26

Scott — Darwin’s science doesn’t predict the future, it explains past patterns.

Imagine if someone was always attacking Darwin because that were pretending that in order for Darwin to be of value he had to be making arguments about what direction evolution was going to take. That’s just bad science.

Well, that is the perspective you are always imposing on economics, and that s just bad science.

No one needs to be in a position to prospectively say when monetary policy is too expansionary or too contractionary for them to be in a position after the fact to explain what causal patterns occured in the past, and what causal mechanism was in play accounting for it.

Do you understand that?

Now, it is simply *not* true that anyone must be prospectively knowledgable of when the markets are pushing too many production channels too far across time, a change in valuation relations across time effected in part by changing money and conditions and by optimism and by changing evaluations of risk and potential return.

This may reveal itself after the fact — just as prospectively we may not know where natural selection may take us, after them fact we may explain how and where it has taken us.

But I question your sincerity in wishing to honestly address these realities about explanation involving essentially complex phenomena like evolution and the trade cycle.

You are hell bent on ignoring complications, and on looking for the cheapest and most superficial argument at hand against any complication in your way. And as you always will, you will find them ad just the most impossible thing the most plausible simply as a matter of expediency and convenience.

Scott writes,

“If someone is going to argue that monetary policy is too expansionary or too contractionary, that will presumably be based on publicly available information. That information set is available to both the central bank and the public. So it’s factored into asset prices.”

“Here’s where I disagree with many economists. They seem to think that they can see flaws in Fed policy that the markets can’t see. Thus they see an easy money policy in 1929 leading firms to construct the Empire State Building, and these perceptive economists understand that it will all end in a crash and the ESB will end up being a white elephant by 1932, but the businessmen who plan and build the structure don’t see that easy money in 1929 will have that effect.”

11. August 2013 at 06:41

Greg, The analogy is completely off topic. If you can’t point to publicly available information suggesting that policy is too easy, how can you claim it is too easy?

17. August 2013 at 05:14

“If you can’t point to publicly available information suggesting that policy is too easy, how can you claim it is too easy?”

You can’t point to any public information of NGDPLT growth being 5%, and yet you claim money is too tight when it is below that (or whatever other ideal number suits the day).

The way Greg claims money is too easy is the same way you claim money is too tight. He, like you, has a non-empirically derived theory of what money SHOULD be, and he measures what money happens to be empirically against that theory.

We can all agree 100% on the empirical data. We can all agree on the history of prices, spending, employment, demographics, all historical events.

But all of this historical data does not tell a story on its own. If I look at a series of charts of historical data, those charts will not form an interpretation, an understanding, for me or anyone else.

In order to tell a story, we have to include ourselves in some respect into the organization of our understanding of reality in order to make economic sense of the historical data.

You are doing this every single time you observe the history of NGDP and then tell a story using that data on your blog. You just don’t realize it because you don’t consciously include self-reflective activity which is a must in all economic thought, indeed all thought whatever.

You believe your theory is derived empirically, even though it is not derived that way at all. We could all agree on historical events, but have vastly different interpretations of why things took place the way they did. Why is that? It is because we are introducing different a priori theories into our story telling.

The only way to settle economics disputes is through debating theory A versus theory B, not theory A as against history versus theory B as against history.

Philosophers of science tried to get around this problem by insisting that the only theories from which we can know anything about reality, are theories that can be tested against history. All other theories are theories from which we can’t know anything about reality. The latter are “not scientific.” We call this positivism.

Notice the contradiction that these propositions are non-empirical ones? Positivism didn’t overcome the fact that we still need a priori theory to understand history. Positivism’s non-empirical presupposed propositions include, but are not limited to: historical laws do not change over time, and, humans are incapable of ever understanding reality through non-empirical self-reflective activity, etc.

If you observe 5% NGDPLT taking place for example, then you will think “money is pretty much just right”, whereas someone else might think “money is far too loose”, whereas someone else might think “money is far too tight.” All three people can agree that NGDP is 5%, but have different interpretations of it, due to thinking a different a priori theory to be the right one.

3. September 2013 at 05:45

[…] nevertheless supplied some reasons for my having characterized his thinking as I did. For example, when Scott writes that "asset prices should reflect fundamentals. Interest rates are one of the fundamental factors […]

7. June 2015 at 16:41

[…] of whom, he made an apposite comment about low discount rates and asset price […]