Krugman on fast recoveries from big recessions

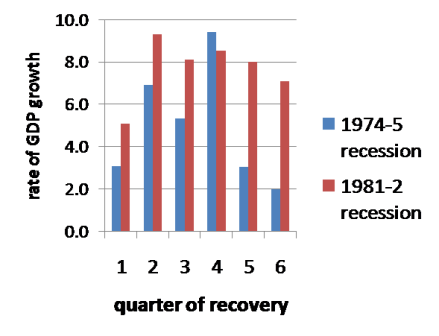

Paul Krugman has a very important post showing fast recoveries from previous big recessions. The 1983-4 recovery was particularly fast. But lest anyone think Reagan might have done any good he points out that a rapid recovery also occurred in 1976. So how did they do it?

BEA

BEAI decided to go back and look at the data on fiscal stimulus, and was quite surprised by what I found. In both earlier recessions the budget deficit rose by just over 3% of GDP; from a bit under 1% to 4% of GDP between 1973 and 1975, and then from 3% to just over 6% between 1980 and 1982. I’m no expert on Keynesian economics, but isn’t that mostly the effect of the recession? I don’t see a lot of room for discretionary stimulus. And if we look at the especially fast 1983-84 recovery, we find that the discretionary stimulus that did occur was exactly the kind that Krugman says doesn’t do much good—tax cuts for the rich (who have a lower marginal propensity to consume.)

How about the current recession? I agree with Krugman that without more stimulus we are likely to have a very slow recovery. I hope I am wrong, and I admit that forecasting is very difficult. But I also wonder how a Keynesian would explain the expected slow recovery. Yes, we haven’t done as much as Krugman would like, but this time the budget deficit is rising from roughly 2% of GDP in 2007 to 11.2% in 2009; nearly three times the increase that occurred in the other two big recessions. And this time none of the stimulus is going to tax cuts for the rich. It seems like Krugman should have expected this recovery to be much faster than the 1976 and 1983 recoveries. And yet despite the fact that dramatically higher budget deficits seem to be associated with a much slower recovery, the logical solution seems to be . . . even more massive budget deficits.

Now I am sure that a good economist could find flaws with my analysis. Other things are never equal. I suppose one argument is that continuing banking problems make recovery more difficult this time. Or the overhang of unsold houses. Of course in 1983 there was an overhang of a lot of heavy industry in the rust belt that was gone for good. And the fast 1933 recovery occurred in the midst of severe banking problems.

But let’s suppose the recovery is held back by special factors, doesn’t that still beg the question of why the previous recoveries were so fast? In his previous post Krugman had plugged in the fiscal stimulus numbers and showed that the slow recovery we are getting is exactly what one would expect from the Keynesian model. Boy, am I happy to hear that!! I was getting tired of Keynesians telling me that the real reason for the fast Reagan recovery was not supply-side economics but rather “good old Keynesian deficit spending.” But we now know from Krugman that the Keynesian model predicts that even if Reagan had done three times as much deficit spending (and by implication far more than three times the discretionary stimulus) the recovery would have been expected to be the sort of anemic 3% plus recovery we are expecting this time. Sure, you can quibble a bit with the numbers—income tax receipts are more cyclical than during earlier decades, so that explains some of the bigger deficit this time. But I don’t see how any amount of fiddling with the numbers will explain the 1983-84 recovery using a Keynesian model of stimulus. So the fast recoveries of 1976 and 1983 remain a mystery.

I think Krugman’s best argument would be that this time monetary policy is stuck in a liquidity trap. The Taylor Rule says we need negative nominal rates, and yet we have no way of getting them. I agree that monetary policy is the key. Where I disagree (as you all know by now) is that I think there are all sorts of ways of making monetary policy much more expansionary:

1. Negative rates on excess reserves.

2. Actual QE, not fake QE.

3. Most importantly an explicit NGDP target path, level targeting.

But at least Krugman sees the real problem. I think most of the profession has still not realized how much more stimulus we will need unless we want millions of workers to remain unemployed far longer than necessary. His views are certainly preferable to Chicago School economists arguing that the relatively mild nature of this recession shows that fears of a severe recession were overblown. So kudos to Krugman for raising the alarm. BTW, I once heard a talk by Robert Lucas where he argued that despite the flaws in his model, Keynes was a great man because he had the basic insight that the Great Depression was unacceptable and it was up the the government to do something about it. I agree. Perhaps DeLong will have to add Lucas’ name to the good old Chicago School.

I’m sure there are errors in my analysis and look forward to the response of my Keynesian readers.

Tags:

31. October 2009 at 17:19

Not claiming an error on your part, but Krugman has argued in the past that the last two US recessions were the bursting of private sector bubbles, while the earlier episodes you refer to were the result of deliberate disinflation by the Fed. (I emphasise “deliberate”!) Therefore there was a lot of pent up private sector demand when the Fed lowered rates to normal levels.

Eg “they’ve proved hard to end . . . precisely because housing “” which is the main thing that responds to monetary policy “” has to rise above normal levels rather than recover from an interest-imposed slump.”

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/02/10/postmodern-recessions/

This mostly comes down to the liquidity trap in the end, as you say. But I think there is a bit more to the “above normal levels” argument. (Something Austrian!? Oh, the irony . . .)

31. October 2009 at 18:21

Monetary Policy + Fiscal Policy = Result

Case A:

Fiscal Policy weak, result good

Case B:

Fiscal Policy strong, result bad

Possible Conclusions:

1) What was happening with monetary policy again?

2) Is fiscal stimulus harmful

3) Is fiscal stimulus irrelevant

4) Maybe only permanent fiscal policy matters*

* A permanent expansion of debt by the government contributes to broad money growth. (An expansion of debt that is considered unsustainable (must be paid off) operates no differently than a temporary inject of narrow money.)

31. October 2009 at 18:41

The Great Depression was caused by bad monetary policy, combined with bad bank regulation (prohibitions against interstate branch banking and prohibitions against private bank note issue). It was exacerbated by protectionism (Smoot Hawley) and the Fed’s causing banks to raise reserve requirements in 1937. Not to mention some ill-timed tax hikes. All of these were the effects of government–and yes, the Fed is a governmental institution, legal fiction to the contrary. (It was created by an act of legislation by Congress, and presumably could be abolished by America’s only native criminal class.)

Professor Lucas was nodding.

31. October 2009 at 19:05

Bush also ran a very Keynesian economy–lots of deficit spending financed by foreigners (so little crowding out), wars, and tax cuts; with poor economic results.

One possibility is that the economy has seen a deflationary structural shift. Technological advances and trade reduce prices in tradable goods. So they improve consumer welfare, but lead to a small growth in measured GDP. But since wages are sticky, and public school systems are bad; employment lags as well.

If so, we could take Greg Clark’s idea of wage subsidies seriously. Government subsidies may be the only way to get nominal compensation growth.

31. October 2009 at 19:55

Declan, After reading that piece I suppose Krugman would say it was the liquidity trap, as I don’t think he’d use an Austrian argument. No, make that I’m sure he wouldn’t use an Austrian argument. I suppose most people are interested in the current recession, but I was most surprised by the implications of Krugman’s argument for the earlier recessions. His numbers pretty much drive a nail in the coffin of the argument that the Reagan recovery of 1983 was due to Keynesian demand-side fiscal stimulus. Krugman certainly knows his Keynesian multiplier models, and if his numbers are even close to being right then the robust 1983 recovery was either supply-side economics or simply the self-correcting mechanism. Money wasn’t particularly easy in 1983 (when one accounts for the fact that interest rates were high, even in real terms, and NGDP growth was not particularly fast compared to the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Jon, A lot of questions, but what do you see as the answers for each recession?

Bill, I think Lucas would agree that Fed errors caused the Depression. The debate in 1933 was whether the government had a duty to fix the problem they caused. Lots of conservatives opposed stimulus. Keynes favored it, and Keynes was right. But he wrongly focused on fiscal stimulus, whereas monetary stimulus was far more effective.

Thorfinn, I’m not crazy about structural explanations (although they might play some role), because they have no impact on NGDP growth, only the way it gets partitioned between RGDP and prices. And right now I still think the problem is too little NGDP. If we got rapid NGDP growth we might find some supply-side problems as well, as you suggest.

I probably should have emphasized one point more in the post. I don’t think there is any mystery at all as to why this recovery will be much slower than those earlier recoveries from deep recessions. To me the answer is simple—monetary policy is far more contractionary this time around.

I suppose I am about the only person who looks at things this way; although if Milton Friedman was alive he might agree with me, as he called Japanese monetary policy highly contractionary despite massive increases in the monetary base and despite near zero interest rates. But I don’t see very many other conservatives making that argument–certainly not Anna Schwartz and Alan Meltzer.

I didn’t know Greg Clark was advocating wage subsidies. I’ve always favored that policy, and I recall that Phelps has also been a strong supporter over the years. There doesn’t seem to be much support in policy circles, perhaps it would be difficult to administer.

31. October 2009 at 22:58

Scott: I’ve never tried very hard to figure it out, but I believe that the data does not support a firm conclusion on fiscal policy at this time.

My feeling is that monetary policy was expansionary then and not now–which is in line with your sentiment. But its precisely because of this that I don’t think a monotonicity argument can judge fiscal policy at this time.

#4, I mentioned because a recent WSJ article was stuffed with quotes from businessmen saying, “I think I can expand my business because of xyz, but I see a lot of risk regarding changes to the tax laws. Given that uncertainty, expansion does not seem prudent right now.” Notably absent from their claim was a statement, “I think NGDP is going to be below trend”.

I think the posture of our government is very anti-growth right now. People expect tax-rates to go up–new tariffs, carbon taxes, income-taxes, fica increases, new employee fees. The minimum wage has been progressively pushed upwards even as a general deflation takes hold. People expect new regulatory “taxes”. People are realizing ‘cash for clunkers’ was ‘cash for capital destruction’. People are thinking “great all that stimulus” but in 2010 the government is going to have to start paying down that debt. The wheels of business are sticking: a pay czar, Senators tell GM to buy more palladium, government suddenly revises labor rules against Ford, etc, etc.

1. November 2009 at 00:30

you have convinced me to short the market again. actually, the tremors last week got me short, but now i feel better about it.

1. November 2009 at 03:43

1. There is always the very real possibility that fiscal stimulus (in the form of spending) increases recessions.

2. If the short term spending stimulus multiplier is less than 1 (which some people have been arguing), this is what we would expect. In this case government spending crowds out private spending, but uses the resources less efficiently, so we stay in recession longer than we would have without the stimulus spending.

3. If it really is a function of fear of government regulatory and taxing powers, then is/when the health care bill dies we should see a really solid uptick in growth shortly thereafter.

4. I’m going to play the devil’s advocate here and say (for the sake of playing the devil’s advocate!) what if it wasn’t normal monetary stimulus that helped but rather the protracted inflationary recession due to interaction of inflation and minimum wage. Here we go:

Monetary stimulus was probably more effective in the seventies and early eighties due to the very high minimum wage. By causing inflation, the fed destroyed the damaging effects of the minimum wage. However some forms of fixed cost are more resistant to removal by inflation minimum wage was; regulatory and tax burdens are a good example of this. Which brings me to my last point.

5. Lastly: I have to agree with Jon, also, from what I have been reading and talking to people about… it seems they are more worried of regulatory and tax policy than any other worries. (I include the new rules for medical benefits in this.)

1. November 2009 at 05:13

Scott,

As I recall, Krugman’s explanation for the expected slowness of this recovery is the difference in the unemployment rate increase over the course of this recession versus the others. And he defines the need for stimulus mostly as a function of the unemployment rate rather than the expected duration of the recession per se. I gather recession ends are not defined as a function of either unemployment changes or unemployment reversals. Also, a number of bloggers have pointed to the greater average length of unemployment in this recession.

1. November 2009 at 06:04

“Negative rates on excess reserves”

This solution when suggested always scares me. How would it work in practice? In effect isn’t it forcing banks to pump credit into the economy? Would this not lead to even more marginal (mal)investment into various sectors of the economy that may not generate return on investment.

1. November 2009 at 08:38

Count me amongst those who think that regime uncertainty is definitely a force holding back economic growth and increased hiring.

Here are a couple of illustrative anecdotes such as this and http://www.coyoteblog.com/coyote_blog/2009/10/what-a-freaking-mess.html“> this from an entrepreneur who graduated number one in his class at Harvard Business School (I don’t know what year).

That said, Scott has me convinced that a mismatch of supply and demand for money is the thousand pound gorilla here that everyone seems to be ignoring.

1. November 2009 at 08:40

Ok, I botched the html in my last post. Sorry. It looks like both links work though.

I wish we had a “post preview” option. 😉

1. November 2009 at 08:41

By the way, that first link is an illustration of how jobs that could have been saved were in fact not saved due to Obama’s blundering.

1. November 2009 at 08:48

But I don’t see how any amount of fiddling with the numbers will explain the 1983-84 recovery using a Keynesian model of stimulus.

Take a look at what interest rates were doing between 1981 and 1983. Depending on the rate you look at, you will see a drop of about 6 or 8 points, from around 15 percent to arount 8 percent. The drop in real rates can’t have been much less. Any Keynesian model should predict an upturn from a fix like that. The main problem with macro models at that time was that they weren’t designed to analyse the effects of input-price shocks. Bruno and Sachs tackled that issue in a book which attracted a lot of attention. Oil obviously played a big part in the 1974 and 1981 recessions and the subsequent recoveries.

1. November 2009 at 13:55

Jon, I agree that we can’t make any estimates right now, and I would add that we can’t ever make any estimates, as the multiplier is a figment of the imagination of economists. It all depends on monetary policy. And ther eis no such thing as an other things equal monetary policy, as economists have never come up with a definition for the stance of monetary policy?

Again, what I found interesting in the Krugman posts is the implication that fiscal stimulus played almost no role in the fast Reagan recovery, even if you buy the Keynesian model(which I obviously don’t.)

rob, I’m not sure how fast the recovery will be, the post was more a comment on Krugman’s views–so don’t sell stocks on the basis of my views. I think Krugman and I agree that if the economy grows at the 3% many are expecting, then that sort of grwoth is inadequate given the depth of the recession. Three percent is just the normal trend growth; although with all the anti-supply-side things happening (and not just Obama, much of this started under Bush) perhaps the trend is 2% or 2.5%.

Doc Merlin,

Those are good points. The 40% minimum wage increase was really poorly timed. Youth unemployment has been especially bad this time around, even compared to 1982.

JKH, Perhaps that is his argument, but if so it is an completely bogus one. The relationship between unemployment and growth is only slightly different from earlier recessions. Certainly nowhere near big enough to explain such a wide dispersion in growth rates. Didn’t Krugman himself in an earlier post criticize those who argue that Okun’s law no longer holds?

In any case the slightly more rapid increase in unemployment would actually make a fast recovery easier not harder. If unemployment doesn’t rise much in a recession, then it is tougher to recover because you have productivity problems, not just AD problems.

And finally, that wouldn’t explain why the recovery in 1983 was so fast without Keynesian stimulus.

V, No it doesn’t at all force banks to pump credit into the economy. They would probably just buy T-bills. It would force banks to pump cash into the economy, which is what we want. Monetary policy isn’t about banks, it’s about cash.

happyjuggler0, Thanks, I’ll take a look.

Kevin, I agree that money played a part in the 1983 recovery (at least relative to this time), although I don’t think it was anywhere near as expansionary as you suggest. Inflation expectations almost certainly plummeted in that period. So real interest rates didn’t fall all that much. In 1981 we had double-digit inflation, by 1983 it was about 4%. We don’t have any market indicators of expected inflation, but I would note that in 1981 we had been having extremely high inflation for 3 years, and fairly high inflation since 1973. So I think it is a good bet that inflation expectations were high. The year 1982 is when actual inflation fell sharply. I’d guess inflation expectations fell somewhat that year, and even more in 1983.

I doubt whether falling oil prices were very decisive in the recovery. After mid-2008 oil prices fell in half, and output plunged. Yes, other things weren’t equal. But I just don’t see evidence that low oil prices are a huge plus for the economy. Perhaps they helped a bit.

I’d guesstimate something on the order of 30% monetary policy, 30% supply-side tax cuts and removal of price controls, etc, 30% self-correcting mechanism once wages adjust to lower inflation, and 10% lower oil prices.

1. November 2009 at 14:04

happyjugglerO, Thanks for those links. I disagree with some conservatives who seem to like our health care system. It is a mess. But somehow Congress has found a way to put together a bill that will make our system even more of a adminstrative mess, even more costly, and still leave 20 million uninsured. Way to go.

The Dems seem to like doctors, lawyers, teachers, and other public employees. But they don’t seem to give a damn about the rest of the country. You could argue this is the Republican’s fault. Eight years of Republican misrule opened the door to this. Just as Hoover made FDR, Bush made Obama.

1. November 2009 at 17:44

Scott

…and Nixon, Ford and Carter made Ronald Reagan (and Paul Volker). Why, oh why, after fluctuating (sometimes with great amplitude) around 850 points in the 17 years between mid 65 (the start of the “Great Inflation” period)and mid 82, the DOW took off and in the next 17 years went from 850 points to more than 12000 in mid 1999? That was the heyday of the “Great Moderation”.

Krugman also says that people have forgotten the marvelous growth of the Clinton years, but I remember well that in 1994 he published “Te Age of Diminished Expectations” and for most of that period was writing in Slate and HBR that growth was too fast (“potential” was just 2%-2.25%, according to him “the speed limit of the economy) and that inflation was “hidden behind the bush” because unemployment could not come below 6%!

1. November 2009 at 20:14

Bill Stepp:

“It [Great Depression] was exacerbated by protectionism (Smoot Hawley)”

Krugman had an interesting argument on tariffs – notably, that they are a legitimate second-best option in a world where central banks cannot devalue the currency (e.g. link to gold, or other causes). I think this is relevant to the dollar/yuan discussion.

JKH writes that many bloggers point to the increase in unemployment duration this time around. They have pointed to this as a sign that the economy needs a big structural recovery. I would agree to some degree, and also note that since the 80s recoveries have been weak:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/TCU

Ssumner has pointed out, however, that the structural economic dislocations in 80s were if anything _more_ severe than those today… So there must be something else at work.

With regard to previous recessions – it’s rather critical to note the debt/GDP ratios this time around. Specifically, the current ratio and the deleveraging trend.

It is no accident, I think, that the debt/GDP ratios in the current crisis approximate those of the Great Depression. Perhaps there is simply some threshhold where debt is soooo high that private business (rationally) anticipates that credit-fueled growth can no-longer be sustained, and this tips the economy into a self-sustaining credit contraction cycle?

The government, it seems, wishes to encourage deleveraging to some degree to avoid future systemic crises (e.g. increase capital ratios, particularly for systemically important banks). Excellent. What I do not think they have fully thought through is how they are going to support price levels when this happens.

The one area where I am sympathetic to the Keynesian argument (and by this I mean the argument that government _consumption_ is essential to kick-starting the economy, which I differentiate from government investment), is the fact that fiscal deficits (that are financed by non-tax revenues) are the primary way to inject money into the economy other than through bank credit. Now, that doesn’t mean we necessarily have to increase fiscal spending right now (our deficits are plenty big – we can simply cover more of those through some permanent money creation). But it does mean that if we want to escape the debt-hole without reflating a credit bubble (that everyone seems to think is unstable), this means fiscal deficits can be helpful to support monetary policy.

But that’s not really what Krugman is arguing… (I think…)

1. November 2009 at 23:17

During the ’82 recession I was at Stern/NYU taking economics courses from profs who worked at the NY Fed across the street. They were real Friedmanite monetarists. In fact, the whole body politic was infected with monetarism then. When I was having breakfast at the corner diner the radio would announce the week’s money supply figures along with the sports, weather and business reports.

For what that’s all worth. I just mention it in the spirit of noting how things change. All that, of course, was a huge reaction against the Keynesianism that had screwed things up just a few years earlier and created the mess then, while monetarism had been ignored.

Anyhow, the big obvious difference between the Reagan recession and today’s was that one resulted from inflation going way, way up during the Carter years, then the Fed pushing interest rates way up towards 20% to stop it, then as the economy fell the Fed dropping rates from so high to down low.

It was an inflation-correction recession engineered by the Fed to break the cycle of inflationary expectations that had gotten built into everything. (Again, how things change.) My profs from the Fed went on about that endlessly.

The causation and mechanism of this recession seem entirely different.

From back then I have no memory at all of “stimulus” being mentioned by anybody, anyhwere. Lots of people wanted interest rates lowered — farmers marched on Washington and drove their tractors around the Fed and Capitol and all about that. People on McNeil-Lehrer (remember McNeil?) argued about interest rates all the time. Nobody mentioned stimulus.

As you’ve noted, stimulus was illogical in concept — if the politicians had stimulated the economy, the Fed would have had to raise rates that much higher to get inflation down to where it wanted.

My profs hand-waved away the concept of stimulus as an obsolete Keynesian idea — saying that in practice, because stimulus came out of a political process, it would always arrive very late and be highly distorted towards pork and partisan causes.

All disputes about a liquidity trap mandating a stimulus aside, I don’t see anything proved wrong today about those two observations.

2. November 2009 at 01:22

There are many economists who seem to assume that the indestructible dollar will never be assailed or supplanted by another world currency. There are also many who confidently argue economic stimulus remedies from purely inside America’s borders. What many here fail to see is what is actually happening to the foreign US dollar right now. What must be conceded by any economists, particularly Monetarists, is that if the dollar falls, therewith goes also the economy.

What has been ignored by most economists is that foreign creditor economies outside America’s borders, upon whom America is so deeply dependent and indebted, barely gets a mention as a real problem. It is widely assumed here that these creditors are all in the symbiotic Dollar Trap with America. Therefore no creditor nation will want to destroy the dollar — this would indeed be suicide. The impression also mistakenly given is that the American govt is in control of the dollar. Right now, I would question this as perhaps an unsubstantiated view.

My own belief, in a nutshell, is that China now has control over the dollar via the gold markets. In an all-in-one strategy China has found a way to discreetly buy up all her own gold(China is now the largest producer of gold in the world), slowly but surely buy gold on the markets with her excess dollars whenever the US govt floods the gold market to maintain dollar strength(China buys gold safely in these dips), simultaneously moving her Yuan confidently towards a partial gold standard as well as constantly weakening the US gold holdings, all the while steadily dumping her dollars slowly and surely within this process.

That’s what’s happening now. If we assume that the Chinese also now have control over the dollar in this way, the US govt can do absolutely nothing to stop China in this play. Add to this that China has just issued her own Yuan Bonds as well as allowed all of her populace to buy as much physical gold and silver as they like — all 1.3 billion of them — and perhaps you can see the growing danger here.

What eventual effect will this have on the dollar? What must happen?

All the evidence for this is better explained and evidenced in the following articles that I’ve written:

http://slowsmile.hypocrisy.com/2009/09/12/the-beijing-defence-against-americas-economic-rollercoaster/

http://slowsmile.hypocrisy.com/2009/10/07/slow-death-of-the-petro-dollar-is-confirmed/

The other thing to consider here is, if China really does control the dollar now as I’ve suggested, who then is really in charge of the US markets and economy ?

Because of this gold situation, the Chinese will set their own preferred floor on gold price — their own preferred dollar value if you like; they will continue to dump dollars slowly and accrue gold. That is, until China’s dependency on the dollar — perhaps a few years down the line — is not longer a problem.

Then what will happen ?

As I’ve said, if anyone now assumes that all creditor nations within the Dollar Trap would prefer all their Treasury savings and dollar value to be “inflated away” by FED policies as legitemate policy, I honestly believe now that this is a very stupid and flawed assumption, since with China now in charge of the dollar value via gold this is very unlikely to happen now. China and probably other creditor nations will, naturally, start to defend their savings with gold, which is perhaps the dollars oldest and most effective enemy.

2. November 2009 at 01:55

The year 1982 is when actual inflation fell sharply. I’d guess inflation expectations fell somewhat that year, and even more in 1983.

That kind of argument only serves to shift the graph of ex-ante real interest rates a bit to the left or right. You’re stuck with the fact that the graph has a huge peak (or two) in it. And really, how do you square this idea, of inflation expectations lagging behind reality, with your other views?

2. November 2009 at 05:01

Thanks. So if I understand correctly banks instead of holding reserves will buy and hold T-bills and thus release the cash into the system. Would the negative interest rate then need to be adjusted to maintain inflationary expectations in a tight band.

2. November 2009 at 07:54

marcus, Thanks for the tips on Krugman’s earlier writings. It shows the folly of targeting real variables, like real GDP or unemployment.

statsguy, It is true that Keynesian theory implies protectionism may be a second best policy, but the theory is wrong. The Smoot-Hawley tariff severely damaged the US economy just at the moment (spring of 1930) when there were a few green shoots. Krugman’s mistake (and Keynes’ as well) was to think about tariffs as a trade policy, something that increased the trade surplus. But their impact on AS/AD is much more powerful. Under a gold standard they reduce world AD, and hence are deflationary. Commodities prices crashed on news that Smoot-Hawley was moving forward in 1930. And they also hurt the supply-side of the economy. Indeed under a gold standard these effects are related, as adverse supply shocks reduce the equilibrium interest rate, and Larry Summers (of all people) showed that lower interest rates encourage gold hoarding, and thus were deflationary under a gold standard.

Regarding the link between monetary and fiscal policy, I wish it were true. But despite the fact that the national debt is expected to rise from 40% to 75% of GDP, inflation expectations remain really low. So I still think the focus should be on monetary policy through unconventional means like explicit nominal targets and discouraging ERs, not fiscal stimulus.

Jim Glass, You said;

“It was an inflation-correction recession engineered by the Fed to break the cycle of inflationary expectations that had gotten built into everything. (Again, how things change.) My profs from the Fed went on about that endlessly.

The causation and mechanism of this recession seem entirely different.”

I see why you say this, but the more recent recessions haven’t been quite as different as you might think. The 1991 recession and the 2001 recession both reduced the trend rate of inflation (from 4% to 3% to 2%.) So far this one has been the same, inflation has fallen again. So although I agree that the intent was not to reduce inflation, as in 1982, the effect was the same. All these recessions have been negative nominal shocks. All have been triggered by tight money, whether interest rates were 20% or 2%.

But despite this quibble, I agree with almost everything in your comment.

Bill, I don’t see much evidence that the Chinese are following this policy. Have they dramatically reduced their holdings of dollar assets? I was under the impression that they were increasing their holdings of dollar assets.

And I am not concerned about a decision by the Chinese to hold less dollars. That would be up to them, it would not have much effect on the US economy.

Kevin, I was arguing that it isn’t clear that there was any sharp fall in real interest rates. So I think that is relavent to your argument, as you claimed real interest rates fell sharply.

Even the Fed itself didn’t forecast or intend inflation to fall nearly as fast as it did. Unexpected movements in actual inflation are perfectly consistent with Ratex. Now we know that 1982 was a turning point in world history, the end of the Great Inflation. But I recall that in 1981 inflation had been trending upward my entirely life, almost no one could imagine a much lower inflation environment, especially as deficits were getting much bigger. In retropsect the low inflation looks obvious, but at the time it was thought to be a temporary downward blip due to the severe recession. Nominal interest rates stayed much higher than inflation for a number of years, until people gradually realized that the Fed had a new and more effective policy regime. But during the long upswing in inflation there were many promises by policymakers to do something about it, but they were all empty promises. So some degree of skepticism was warranted.

V, Yes, or even better some of the ERs would need to be withdrawn through open market sales to prevent an outbreak of high inflation.

2. November 2009 at 07:57

Sumner 4 Fed Prez

2. November 2009 at 09:04

Scott,

Here’s the recent example of Krugman’s emphasis on employment rather than on GDP growth per se as an indicator of both the nature of the recovery and the need for more stimulus:

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/02/opinion/02krugman.html?_r=1

2. November 2009 at 09:30

@ JKH

Thats fairly standard for Keynesians. They see high unemployment as a sign of inefficiency in the market that needs to be fixed though government spending. I think part of the reliance on unemployment statistics stems from difficulty extracting actually useful macroeconometric data.

2. November 2009 at 10:20

Hey Scott, do you have any thoughts on Roubini’s latest FT column, http://www.rgemonitor.com/roubini-monitor/257912/mother_of_all_carry_trades_faces_an_inevitable_bust ??

2. November 2009 at 11:01

Thanks Mark, but I wouldn’t be a good president. How about FOMC member? Then my views would at least be heard by the others.

JKH, I agree we need more stimulus, but in contrast to Krugman I think monetary stimulus is far more effective. It is interesting that he claims the slow recovery is a sign of success. Unemployment is now much higher than Obama predicted it would be if we failed to enact his program. So how is 10% unemployment a success?

Both GDP and unemployment tell the same story. NGDP is 8% below trend, and unemployment is double the natural rate. Either way we need much more stimulus, as Krugman suggests. I agree that 3-4% real growth rates will leave unemployment unacceptably high for years to come. But we shouldn’t be targeting U, as we don’t know the natural rate. There is no natural rate of NGDP, which makes it a good target.

Doc, I’d say the Keynesians are half right. High unemployment does indicate there is a problem, but it isn’t a good target for demand management (fiscal or monetary.)

Robert, I’m not a fan of Roubini’s stock forecasts, nor his macro analysis. On the other hand he provided the best forecast of the economic crisis of anyone I know of.

This spring he said don’t buy stocks; if I had followed his advice I’d be 40% poorer now. His macro analysis seems to confuse ex ante with ex post. Interest rates are not negative 10% or 20%. The correct way to measure them is by looking at the forward markets for currencies, not the ex post change in the exchange rate.

It is certainly possible that he is right that equities are not a good buy at this level. I don’t forecast stock prices, but they are almost as likely to go down as up. I was surprised when he said conventional wisdon expects a V recovery. Most forecasts I see are showing rising unemployment into 2010. In a V recovery such as 1983, the unemployment rate starts falling almost immediately. I agree with him that that is unlikely this time, but I don’t agree that a V recovery is conventional wisdom.

2. November 2009 at 11:09

Scott,

Off topic, but I wanted to draw your attention to a speech that Lawrence White recently delivered. In it, he stated:

—–quotes—–

Milton Friedman long called for a “quantity rule” reform that would replace the central bank’s discretion in monetary policy with a non-discretionary algorithm … Another quantitative type of rule, Hayek’s proposal of 1931, would direct the central bank to target nominal national income (GDP).

—–quote—–

White doesn’t elaborate, and its source is not clear, but Hayek’s rule seems very similar to what you propose. Do you know anything about this? Here is the link:

http://www.efnasia.org/attachments/White%20EFNkeynote%20Cambodia%2009.pdf

2. November 2009 at 12:36

Wouldn’t targeting 5% NDGP growth have stifled the 1983-84 recovery?

2. November 2009 at 13:17

Scott, you said:

“Interest rates are not negative 10% or 20%. The correct way to measure them is by looking at the forward markets for currencies, not the ex post change in the exchange rate.”

Roubini does not confuse ex post and ex ante, and it is important to understand that he isn’t talking about equilibrium situation. Roubini says that asset markets have received a stimulus comparable to -10-20% short term interest rates. Marginal traders who set prices in the market at this moment do not look to the currency forward markets for interest rate information, they look at the asset class correlations. His column is a big warning that ex post will not look like ex ante, and is directed at such marginal traders.

2. November 2009 at 13:46

Roubini column is basically corrrect. The real puzzle is the size of the coming stock market correction – will it be 5 percent or 50 percent. Problem is Roubini gives no model that could quantify the effects.

2. November 2009 at 13:49

123, re Roubini, doesnt it seem more likely the causation runs in the other direction? that the dollar has depreciated because speculators have been more willing to invest in riskier, international assets, not that they invested in those assets because they expected the dollar to depreciate? it seems very silly to describe the capital gain on a currency position as comprobable to an annualized interest rate, leaving the impression the traders dont understand that exchange rates tend to be volatile.

2. November 2009 at 14:01

Rob,

models that traders use don’t understand that.

2. November 2009 at 14:31

ssumner:

“I wish it were true. But despite the fact that the national debt is expected to rise from 40% to 75% of GDP, inflation expectations remain really low.”

Precisely because the Fed is sterilizing this deficit… If the Fed merely announced that it was going to fund it with permanent dollar creation, we’d see inflation almost instantaneously.

Instead, we get the Fed announcing that it’s buying up mortgage bonds and agency debt (to free up bank balance sheets – a huge hidden subsidy), BUT the Fed has every intention to buy it back up just as soon as it can.

2. November 2009 at 14:44

… sell it just as soon as it can.

2. November 2009 at 19:39

What is not conceded by Krugman is that the current US National Debt is a problem. Of course, this is all that Krugman ever quotes, so adamantly maintaining that this debt is, in effect, quite small. But if you throw in deficits, foreign debt and fiscal debt liabilities, the total US debt becomes $120 trillion and this can hardly be regarded as trivial — a debt is a debt after all. Notable also, I’ve just read that the US govt is paying back the National Debt at a rate of 1.2% of GDP(2009). When comapared against the US Total Debt, I therefore regard this payback amount as a joke.

And since the whole world now realizes that the FED is trying to inflate away American Debt, is it not reasonable to assume now that creditor nations have all clocked this play, and are now carefully working towards policies that rebuff these damaging US monetary policies in order to preserve their own savings within their own economies? I believe that to assume otherwise is short-sighted and very dangerous indeed.

In one of my links in my last comment, it is apparent that China, Japan, Russia, France and the Gulf States are now overtly dumping the petro-dollar for the euro. Iran has recently taken the same action. Therefore we can safely assume that, since these countries wont be paying for oil with dollars then they will not need to accrue so many trade dollars. Therefore, by extension, all these countries will not be buying such large quantities of US Treasuries. So the global rate of purchase of US Treasuries is bound to decline. Your reaction to these events as fairly trivial is strange.

The whole basis of the debt/US Treasury cycle for funding US debt depends wholly on foreign creditors purchasing US Treasuries. But it is really a little more than this. This whole cycle urgently requires that the rate of Treasury purchase must ever increase with the growing US debt — and as I’ve explained — this is clearly not happening. I regard this as a BIG economic problem for the US govt, since confidence has clearly been lost in the dollar by many creditor nations and, like it or not, they are now adopting policies which are not beneficial to the greenback which partly manifest as accruing less US Treasuries in defence of their own currencies and economies.

Even if you do not believe that China is now controlling the gold price, the dumping of the petro-dollar is certainly a large enough problem to cause the American economy to continue in its downward, volatile and unsettled trend for some years to come.

Like it or not, not all creditor nations adopt heavily debt-ridden Keynesian policies because there is simply no need if you have savings or a surplus. For Krugman, the ideal situation would be for every nation on Earth to adopt Keynesian deficits and debt for a balanced global economy. Very unrealistic.

Krugman’s stance on all this is that the creditor nations are the bad guys here, how dare they have savings, how inconsiderate that these nations should have adopted mercantilist strategies to the detriment of Western debt-ridden economics. I am slightly amused by Krugman’s inconsistent take on these points, since he has either completey forgotten or is conveniently ignoring the fact that America, just after the the World War 2, became the biggest mercantilist beast on the planet.

2. November 2009 at 22:35

Jencks:

“How dare they have savings…”

Quite the contrary, it’s not their savings… it’s their refusal to accept a devaluing dollar. In other words, the desire to continue to accumulate _international_ savings, which represents an obligation to repay with goods and services in the future, even though the trade surplus diminishes the ability of the partner country to repay in the future. It is the belief that, somehow, they could accumulate net obligations (foreign currency reserves, etc.) by supplying exports without diminishing the value of those obligations.

In a sense, however, you are correct that mercantilism and Keynesianism are united in one concern – that is, the concern over the lack of demand in modern economies. The 19th century mercantilist movement was obsessed at least as much with building export markets as obtaining sources of supplies for raw materials.

2. November 2009 at 22:40

ssumner:

Krugman’s second best case is a bit more sophisticated than this.

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/10/26/fixed-rates-and-protectionism-2009-edition/?apage=2

The basic notion is that, in a fixed-rate regime based on gold (or, in a dollarized economy), tariffs are a second-best option to depreciation (which may be difficult due to the monetary regime). Current dollarized economies, for example, can’t devalue – they are prisoners of the Fed.

I can’t find the Irwin/Eichengreen paper, however, so I don’t fully understand the Great Depression case – the Ecuador case is pretty easy to understand.

2. November 2009 at 23:58

StatsGuy…With China’s switch to gold accrual out of the dollar and Treasuries(slowly and carefully) my view is that, for now, with China in control of dollar value, they will keep the dollar value at a stable level convenient to China’s needs. And although it has been reported that the FED will discontinue QE sometime next year, I believe this is now probably impossible — because the rate of purchase of US Treasuries is currently slowly dropping. As I’ve said, the rate of increase of global Treasury purchase MUST always increase to keep apace with growing US Debt, therefore the US govt and the FED will probably manufacture convenient though inaccurate reasons why they must continue and extend purchasing of their own Treasuries to monetize their debt for a long time to come. For reasons that you must already know, this is a very dangerous longterm monetary policy but the FED will have no other choice.

In your agreeable lack of demand statement, I would further add that it is always inevitable that the manufacturing sectors within modern economies inevitably die due to factors such as expensive union demands, higher salaries and wages, complex business taxes, income tax, higher lifestyle expectations etc., and that these modern economies inevitably become globally uncompetitive within large volume manufacturing, eventually their private economies to morph and bloom into massive financial services vehicles as their only means to economically survive, backed by Keynesian deficit economics as their only possible convenient and abiding economic tenet.

In your comment concerning China’s manipulation of her currency — which I certainly appreciate and do not deny, my view from all the evidence at hand is that the US govt, for decades now, has been manipulating the price of both gold and oil for the dollar’s benefit with impunity, and when such a precedent has been set, I am not at all surprised that China has now learned to play the same game. After all, China has only learned all this from The Master.

3. November 2009 at 06:27

Lee Kelly, Yes, George Selgin wrote a paper on the history of these sorts of NGDP rules. Hayek wasn’t the only one, many interwar economists favored such rules.

tom S. The simple answer is yes. But there are two issues that need to be considered. First, the trend rate of inflation was much higher in those days. So going to 5% NGDP growth would have been an extremely contractionary policy. In contrast, during recent years 5% has been the norm, and thus the economy can easily adapt to 5% growth. The second point is that I favor level targeting. Thus I favor targeting a trajectory or trend line for NGDP, not a growth rate. Because we are currently far below the trend line, I’d like to see faster than 5% growth. The problem is that the Fed has never spelled out a target for either NGDP or inflation, so it’s hard to say what they should shoot for. If we had 8% NGDP growth today, it would probably be about 2% inflation and 6% real growth. That would be fine until we got close to the trend line, at which time we should downshift to 5%, or even a bit lower.

123, So you are saying that if the dollar falls 20% that causes people to expect it to fall another 20%? That would be incredibly stupid of traders, as there is nothing in the 230 year history of the US that points to that conclusion. Indeed most studies suggest the opposite is more likely, the farther the dollar diverges from 0.80 euros, the more likely it is to bounce back toward that long run rate.

123#2, If someone had ignored Roubini last spring, bought stocks, made a 50% profit and then sold them, wouldn’t they be much better off than if they had listened to Roubini? So why should anyone take stock tips from Roubini? Sure, if he keeps predicting stock crashes eventually one will occur, but how useful is that?

rob and 123, I have a very simple explanation for the dollar’s decline. The US economy is now expected to do worse than foreign economies over the next few years. If you look at the history of the dollar, it is very strongly correlated to the strength of the US real economy relative to foreign economies.

Statsguy, I certainly agree about the desirability of an easier monetary policy, but I am having trouble following your argument here. I had thought you were arguing that fiscal stimulus was a way of forcing the Fed to ease. Now you say they may not ease despite fiscal stimulus. But if policy is independent from fiscal stimulus, why couldn’t the Fed ease even if there was no fiscal stimulus?

Bill, You said;

“And since the whole world now realizes that the FED is trying to inflate away American Debt, is it not reasonable to assume now that creditor nations have all clocked this play, and are now carefully working towards policies that rebuff these damaging US monetary policies in order to preserve their own savings within their own economies? I believe that to assume otherwise is short-sighted and very dangerous indeed.”

The bond market is a part of the whole wrold, and the bond market certainly doesn’t fear inflation. Look at the yield on indexed bonds. Also, look at the CPI futures market. If foreigners really were concerned about inflation they could easily hedge in the futures market, or buy indexed bonds.

Krugman does have many good arguments about why the massive increase in the national debt is a tiny problem. And when Bush was elected he had many good arguments as to why the tiny increase in the national debt under Bush was a massive problem. He has lots of good arguments. He’s a skilled debater.

You said;

“So the global rate of purchase of US Treasuries is bound to decline. Your reaction to these events as fairly trivial is strange.”

It may seem strange, but that’s probably because your first comment said it was happening, and you newer comment is a prediction it would happen. I don’t agree with the prediction, and think foreigners will continue snapping up T-bonds. In fact, now that the dollar is low, isn’t is a good time to buy?

I do agree with your criticism of Krugman’s increasingly mercantilist views. But I don’t see why it would hurt the US economy if foreigners sold our bonds. Indeed it might cause AD to rise.

Statsguy, If your reply to Jencks is right, isn’t it the Chinese who get hurt, not us? They send us lots of stuff, and never get repaid. That’s a great deal for us.

Statsguy, That article is a perfect example of what happens when Krugman starts looking at everything through Keynesian eyes. I may seem silly at times, but I don’t view everything as nominal, and nothing as real. Ecuador elects a Chavez-type government, and starts all these crazy policies, and we are surprised that their economy is in trouble? And Krugman’s explanation is they can’t compete with China, although their currency has either depreciated against China, or at times held level, over the past 5 years. And doesn’t Ecuador export coffee, oil, metals, bananas, cut flowers, etc? How is that competing with China?

3. November 2009 at 07:40

ssummer…I fully agree that the the world bond market is important, but if there is a simultaneous switch from the purchase of dollar bonds to euro bonds, as must happen with the dropping of the petro-dollar by certain countries, what will be the trickle down effect, through this de-acceleration of US Treasury purchase, on the ability of the US govt to fund its growing debt? If these countries drop the petro-dollar and use instead the euro, won’t this mean that these countries will have less dollars with which to buy US Treasuries and more euros to buy the oil?

Since the petro-dollar is being dumped so overtly by major economies now with perhaps more countries to follow, the FED will be forced to purchase their own Treasuries and continue to monetize their debt indefinitely. Is this an acceptable or possible indefinite solution? I really think not. Anyway, all major US Bond purchases have already switched to either TIPS or 2-3 year US bonds for now. Long term US bonds are shunned at the moment. All are moving against America’s ability to inflate away her debt, so US Bonds are providing very little remedy and cover for America’s growing debt now as far as I can see.

You also seem to disagree on my prediction that foreign US Treasury purchases will slowly go into decline. As I’ve already explained with the evidence, the overt dumping of the petro-dollar by major creditors must eventually have a debilitating effect on both the dollar and the US economy. There will also be at least 6 months before these effects will be felt economically in the US(this news has only recently been announced).

3. November 2009 at 08:39

ssumner:

“Statsguy, If your reply to Jencks is right, isn’t it the Chinese who get hurt, not us? They send us lots of stuff, and never get repaid. That’s a great deal for us.”

That is the neoclassical response to trade subsidies, and this situation is somewhat similar. So in a sense, yes – the Chinese are getting burned worse. Reportedly, they’ve expressed this to Secr Clinton, and are upset about the devaluaing dollar.

Let’s leave aside strategic trade and endogenous growth theories (which – although the general public does not use those terms – are the underlying ideas behind the notion of “hollowing out”). As you know, I’m sympathetic to those sets of ideas, but I know you are not and there’s a second set of arguments that are valid even for neoclassical trade theorists:

When you say “us” and “them”, there are two errors of aggregation here: one of time, and the other of people. Again, neoclassicists are somewhat dismissive of the issue of trade differentially affecting people (although some advocate adjustment assistance). So let me focus on the issue of time:

You say the US should be grateful, BUT the individuals who benefited from those cheap imports (while running deficits) are not the same individuals who are paying it back. We are fond of saying the US (as a country, which is a useful conceit) has a low savings rate (or a high discount rate, or a short time horizon, or whatever). Even then, it’s easy for a neoclassicist to make the argument that subsidizing savings is a good thing.

But this does not answer the inter-temporal (or intergenerational) question. The real question is: were those borrowed funds used for investment, or for consumption.

Unfortunately, consumption by debt (which is unsustainable), has left _everyone worse_ off in the _present_. China has a legacy of dependence on exporting to a US market that cannot continue paying (a structural dependence that it has struggled hard to shift over the last year). Moreoover, it has accumulated obligations that have already substantially devalued. Certainly, a neo-classicist would argue that a much larger portion of that surplus should have been spent domestically (which is why Scott’s argument that China’s low currency has helped exports which have been critical for development of China’s private sector strikes me as Mercantilist).

The US has a debt hole that future generations must plug. But they got a lot for it, right? They got a good deal, like a family that mortgages their debt to fund an exotic vacation? Even if on accepts that, there is still the issue of WHO got a lot for it? And when the individuals who benefited are different than the individuals who received, isn’t that a heavily distorted incentive? And over time, that distorted incentive leaves future generations with a huge debt – and, unfortunately (if we believe the hollowing out/dollarization-creates-structurally-overvalued-dollar logic), without the means to repay that debt. And all of this is reflected in the current depreciation of the dollar…

But contrary to what the gold fanatics say, that is NOT an argument against depreciating the dollar – in fact, that’s the only way to fix the situation.

3. November 2009 at 10:35

Scott,

many readers would be interested in your reaction to the latest piece by Edmund Phelps, as Krugman could not get past the first paragraph:

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/f71cfc6a-c7e6-11de-8ba8-00144feab49a.html

3. November 2009 at 14:33

Scott,

you said:

“So you are saying that if the dollar falls 20% that causes people to expect it to fall another 20%? That would be incredibly stupid of traders, as there is nothing in the 230 year history of the US that points to that conclusion. Indeed most studies suggest the opposite is more likely, the farther the dollar diverges from 0.80 euros, the more likely it is to bounce back toward that long run rate.”

Yes, Roubini is saying that stupid/trend-following traders are setting asset prices.

You said:

“If someone had ignored Roubini last spring, bought stocks, made a 50% profit and then sold them, wouldn’t they be much better off than if they had listened to Roubini? So why should anyone take stock tips from Roubini? Sure, if he keeps predicting stock crashes eventually one will occur, but how useful is that?”

The worst moment to listen to Roubini is when he is the most popular guest of CNBC (as it was in March), as precisely then Roubini’s views were completeley digested by markets. I’m not sure about his stockmarket forecasts, but his analysis of the economy is very useful.

“rob and 123, I have a very simple explanation for the dollar’s decline. The US economy is now expected to do worse than foreign economies over the next few years. If you look at the history of the dollar, it is very strongly correlated to the strength of the US real economy relative to foreign economies.”

I agree that this is one of the factors causing dollar’s decline.

3. November 2009 at 15:00

123, if Roubini even believed in his own abilities to predict the market, he would set up a hedge fund instead of a market consulting firm. the advantage of being a consultant as opposed to a trader is that it is a lot easier to hide your mistakes. Roubini has the language, demeaner and business model of a conman. how does he know what models traders plan on using? that isnt analysis, its omniscience.

3. November 2009 at 19:56

RE Roubini:

For whatever reason in our society it isn’t considered socially acceptable to come out and publicly say “I’m pretty sure so-and-so is a conman”, even if you are pretty sure it is true. And it is a shame because the market for conmen vs. honest-men would probably be more efficient if people felt more at liberty to suggest so, i.e., short the reputation of others. As is it is, we only punish conmen after they are proved to be so. But I am happy to predict that Roubini is a conman, based upon his language and his actions. (Of course, this is just my opinion.) The fact he has just announced he is massively increasing the size of his consulting firm signals to me all the more that he is a charlatan. If he were sitting across from me at the poker table I would go all in against his bluff.

In his recent “Mother of All Carry Trade Bubbles” piece, his language has all the traces of intellectual dishonesty. What sort of rhetorical device is he using when he says the dollar must eventually reverse and cause panic covering: “because the dollar cannot go to zero”? Is he speaking figuratively? Of course, the dollar could go to zero, theoretically. And of course there is no reason it couldn’t decline against other currencies at an annual rate of 20% from now to the end of time. So why does he say it must eventually reverse because it cannot go to zero — except as a rhetorical device? Has he simply run out of analytical arguments? (I don’t believe the dollar will go to zero or continue to slide from now until eternity, but why must he frame his opinion with empty, emotionally hot language?)

I’m sure there are plenty of people who ran across Madoff whose gut reaction was that he was a likely conman but didn’t feel at liberty to voice what their instincts told them. I’m not suggesting Roubini is a Madoff — just that he is the run-of-the-mill take my super-expensive financial advice conman sort. I’m for calling a spade a spade and I’m as sure that Roubini is a spade as he is that “The Mother of All Trade Bubbles Faces an Inevitable Bust”. That said, I’m short equities again, but it has nothing to do with Roubini’s lurid prognostications.

4. November 2009 at 06:38

Bill, I’m not sure what petro dollars are, or why oil has anything to do with monetary policy.

If foreigners stop buying T-bonds, I don’t see the Fed buying them. Rather the US public will.

Statsguy; You said;

“When you say “us” and “them”, there are two errors of aggregation here: one of time, and the other of people. Again, neoclassicists are somewhat dismissive of the issue of trade differentially affecting people (although some advocate adjustment assistance). So let me focus on the issue of time:

You say the US should be grateful, BUT the individuals who benefited from those cheap imports (while running deficits) are not the same individuals who are paying it back. We are fond of saying the US (as a country, which is a useful conceit) has a low savings rate (or a high discount rate, or a short time horizon, or whatever). Even then, it’s easy for a neoclassicist to make the argument that subsidizing savings is a good thing.”

When people talk about those who lose their jobs from trade, I do have trouble taking their argument seriously. And the reason is simple. Exactly the same side effects occur with technological change. Mechanization replaces workers, indeed far more workers than trade. But I never hear people argue against mechanization, or for a “mechanization adjustment assistance” program. So I have to agree with Krugman (the old Krugman) that most arguments against trade on not based on the valid issues you raise, but rather have some other motive. No one would ever accuse me of being uncaring about those who lost jobs because Edison invented the light bulb, because EVERYONE is uncaring about those who lost their jobs because Edison invented the light bulb.

And yes it easy to make the argument that we should save more, because government policy currently massively discourages savings in all sorts of ways, and those policies hurt our economy in all sorts of ways. So we should either stop discouraging savings, or do some savings mandates as an offset. In my view savings mandates are less bad than high distortionary taxes on labor and capital.

I agree with the entire last portion of your piece, our pro-consumption and anti-savings policies will hurt the next generation. And I agree that a strong dollar is not needed now. I would just add that China plays almost no role in that process. If we hadn’t bought from China we would have bought the stuff from some other low wage Asian country. We need to get our own house in order, and stop worrying about others.

123, I disagree with Phelps. I think the real problem is nominal–too little nominal spending, or AD. I had trouble following his argument, it seemed to be some sort of real argument. I think Phelps has a lot of great ideas for reforming the economy, and he seems to bring them into his essay, but reforming the economy is a completely different issue from solving the shortfall in AD.

123#2, Obviously I disagree with Roubini that markets are predictably stupid about the dollar. I agree with the rest of what you say.

rob, Didn’t someone in Seinfeld say “it’s not a lie if you believe it”? In any case, I think most people who are highly successful in predictions, come to the conclusion that they are smarter than the rest of us. It is human nature to be arrogant in that way. I have probably gradually become more arrogant as this blog has done better. So I don’t think he is a conman, I think he has too high an opinion of his forecasting skll, because he did have an incredibly important forecast that turned out to be totally on the money, when the rest of the profession was asleep. But I agree with you that his recent predictions have been less impressive.

BTW, My EMH opponents tell me people like Soros, Buffett, and Roubini are smarter than the market. Yesterday Buffett made a $34 billion dollar bet on a strong recovery, whereas Roubini sees weakness. One of them has to be wrong, don’t they.

4. November 2009 at 13:30

am i just new to this or what? is seems the new fad is to run and scream that more bubbles are coming. every day there is a new headline. i thought speculative bubbles were supposed to be accompanied by irrational optimism. it seems now instead of bubble mania we have bubble hysteria.

4. November 2009 at 13:40

Scott,

Phelps seems to say that expectations have already adjusted to new expected path of nominal variables, so new stimulus is not likely to be helpful, and only structural adjustment story remains. What is your estimate of time after which you would agree to fix policy to the current expected NGDP path, instead of returning to the old one?

Roubini does not contradict Buffett that much, because Buffett is a very long term investor in a specific undervalued(???) company, and Roubini comments on the near term risks to the economy and asset prices.

5. November 2009 at 06:40

rob, Don’t worry, it is just a “bubble” in bubble theories. The fundamentals say that bubble theory creation will eventually fall back to its long run trend.

123, NGDP is now 8% or 9% below the trend line from mid-2008. How many people do you know who have had nominal wage cuts that put them 8% below their trend line for wages? I got a zero percent raise this year instead of my normal 4%, so that means I am still 4% overpaid relative to the fall in NGDP. For everyone like me, (and there are plenty) there will be others who have lost 100% of their income. To maintain equilibrium in the labor markets everyone would have had to get an 8% nominal pay cut. But wouldn’t it be easier to have the Fed expand NGDP a bit?

I disagree on Buffett. The experts who looked at the deal said it only made sense if the economy had a strong recovery. The premium was pretty rich. Yes, someday America will recover, but time is money.

But then I suppose we should never bet against Buffett, as his track record on stocks is better than Roubini’s

8. November 2009 at 05:29

8% nominal pay cut is only consistent with total inflexibility of labour and other markets, and Phelps thinks this is not the case. Ideas of Phelps are very interesting because we don’t believe that recent interviews with Schwartz have much to do with the ideas of Friedman, and Phelps is just a version of Friedman plus realistic microfoundations minus accessibility.

Your experts disagree with Buffet, who always says he never tries to predict short term market action, and only long term future is important for him. Roubini has never said anything about the long term business potential of railroads, and mega deal of Buffett has nothing to do with the performance of the economy during the next year.

8. November 2009 at 08:40

123, I think Roubini is bearish about GDP for much more than a year, if not he should be telling people to buy stocks.

I don’t follow your 8% inflexibility argument. An 8% pay cut is consistent with total flexibility of labor markets, which we don’t have. I agree with Phelps that there is some flexibility, my pay fell 4% below trend this year as we had a pay freeze, that is certainly a sign of some flexibility, but not enough.

I like a lot of Phelp’s work on labor markets, I just didn’t care for his recent opinion piece

12. November 2009 at 13:59

You don’t have to be bearish about GDP for much more than a year to avoid stocks, as Shiller P/E is at the level of 1987 top.

You said:

“I like a lot of Phelp’s work on labor markets, I just didn’t care for his recent opinion piece”

This is strange because Phelp’s opinion piece is a direct result of his work on labour markets. He thinks that NAIRU is not constant and is subject to structural shocks. He thinks that labour markets adjust to AD shocks quickly (I guess he thinks one year or perhaps two years are enough).

13. November 2009 at 14:07

123, I don’t think Shiller’s P/E ratio is a good basis for investment decisions. Obviously during (temporary) recessions the ratio will be higher as profits are down. Of course if we never recover from the recession then Shiller will have been right.

I like Phelp’s work on reducing the natural rate of unemployment. He also favors wage subsidies which could help in a recession. But we don’t have wage subsidies, we have wage taxes. So we need to boost AD, since their are no supply-side policies in the pipeline. Labor markets often adjust within a couple years, but this shock was much bigger than usual and hence I expect a slower recovery. I think there are also some AS problems, BTW, so I don’t mean to suggest this recession is 100% AD. But one other thing, unlike most other recessions, the AD shock has badly hurt the AS side of the economy (especially banking). So that also makes the recovery slower, but makes the argument for more AD even stronger.

13. November 2009 at 14:17

Shiller’s P/E is ratio of price to PPI adjusted 10 year average earnings, so his model assumes that recession will not be permanent. Recessions have very limited impact on Shiller’s P/E ratio, so I don’t agree with your conclusions.

I’ll think about your reply on Phelps and if I think of something clever I’ll give an answer to a question “What would Phelps say”. I remember I did it here with Friedman and Kling.

15. November 2009 at 09:00

123, I am confused. Stocks prices are now relatively low. If he uses the average earnings over 10 years in his ratio, how is the market overvalued? He must think the market has been pretty consistently overvalued since 1996.

17. November 2009 at 11:23

I guess that Roubini agrees with Greenspan’s irrational exuberance 1996 thesis, his view is validated by the poor relative stock returns since then.

It is interesting that Roubini argues that fast GDP growth next year is dangerous for stocks, as higher nominal long/medium term interest rates would be dangerous for leveraged investments in stocks.

By the way you are gaining cult status in investment community too. I noticed that british millionaire eccentric hedge fund manager Hugh Hendry has mentioned your blog (Vermeer post) at the beginning of his latest Eclectica hedge fund client report. His clients have heard too much inflation risk propaganda, and he thinks that current market consensus underestimates risks of deflationary pressures, so presumably he thinks that his clients will be less nervous if they start reading your blog. His client report is also interesting because of his discussion about China, but his views are close to Pettis than you. Report is here:

http://www.investorsinsight.com/blogs/john_mauldins_outside_the_box/archive/2009/11/16/eclectica-november-fund-commentary.aspx

17. November 2009 at 12:41

You said:

“I like Phelp’s work on reducing the natural rate of unemployment. He also favors wage subsidies which could help in a recession. But we don’t have wage subsidies, we have wage taxes. So we need to boost AD, since their are no supply-side policies in the pipeline. Labor markets often adjust within a couple years, but this shock was much bigger than usual and hence I expect a slower recovery. I think there are also some AS problems, BTW, so I don’t mean to suggest this recession is 100% AD. But one other thing, unlike most other recessions, the AD shock has badly hurt the AS side of the economy (especially banking). So that also makes the recovery slower, but makes the argument for more AD even stronger.”

Phelps emphasises asset price channel of stimulus effect. The question is why more stimulus might decrease real prices of assets. Perhaps additional stimulus can increase risk premia and real interest rates if authorities have not enough credibility due to time inconsistency problem. Phelps might also think that weaker dollar will be associated with lower real asset prices.

18. November 2009 at 19:04

123, Thanks, You’d be amazed at the number of people who have told me about the Vermeer link. I had no idea his newsletter was so popular. I should say that I basically agree with Pettis about what’s happening right now in China. I think there are lots of distortions. I focus on the “glass half full” more than he does. And I am more optimistic that reforms will gradually make things better. But Pettis is right that China has lots of problems. My point is that China can grow at 10% despite lots of problems. Mexico can’t do that.

Question: I heard a stock guy say the S&P500 P/E is currently 19, but 15 against estimated 2010 earnings and 12 against 2011 earnings. What do you (or Shiller) think of that sort of justification for high stock prices?

123#2, I suppose if the stimulus is too wild and unpredictable is could increase risk premia. But a clear and predictable target for NGDP would help. BTW, it would boost asset prices and therefore also boost the value of institutions (like banks) which have been badly hurt by falling asset prices.

FDR’s 1933 devaluation injected huge uncertainty into the economy. But it was reflationary, so asset prices soared almost immediately.

20. November 2009 at 14:30

Scott, you said:

“You’d be amazed at the number of people who have told me about the Vermeer link.”

It was a happy coincidence, as Hugh Hendry’s client report (he should have about one hundred clients) was picked up by John Mauldin’s free weekly investment e-mail with an audience of one million readers.

S&P P/E on 2011 estimated operating earnings should be used with caution, as:

1. Shiller’s P/E10 uses net earnings, not operating earnings that exclude exceptional items

2. 2011 estimate assumes earnings close to the top of long term earnings growth range, so high multiples on 2011 estimate are not justified

3. 2011 estimate includes profits of financial institutions that are based on relaxed accounting rules

4. 2011 estimate is based on V shaped recovery that is much faster than two previous recessions – this is one of largest risks for current stockmarket level

5. Expectations of low macro volatility from Great Moderation era are no longer with us, so high multiples on 2011 earnings are not a certainty

6. 2011 earnings are two years away

In a nutshell, at 1987 top market multiple on expected 1989 operating earnings was close to 12.

You said:

” I suppose if the stimulus is too wild and unpredictable is could increase risk premia. But a clear and predictable target for NGDP would help. BTW, it would boost asset prices and therefore also boost the value of institutions (like banks) which have been badly hurt by falling asset prices.

FDR’s 1933 devaluation injected huge uncertainty into the economy. But it was reflationary, so asset prices soared almost immediately.”

Devaluations during deflations have no big time consistency problems, that is not the case with other stimuli.

Half of the country thinks Obama is wild and unpredictable.

During last two weeks news about new stimulus in Japan has resulted in a sharp Nikkei drop.

Popularity of decoupling thesis means that stimulus leaks abroad, and there is some risk that NGDP target would increase commodity prices relative to price of domestic stocks. Current capital flows support this, as funds flow from domestic stock mutual funds to international funds.

21. November 2009 at 13:46

You said:

“I suppose if the stimulus is too wild and unpredictable is could increase risk premia. But a clear and predictable target for NGDP would help.”

Switch to NGDP 5% level targeting would be useful if the target path starts at 2009 Q3 NGDP. There would be absolutely no time consistency problems as many economists forecast that NGDP growth will follow this path anyway.

It would be desirable to have a higher base of target path, but starting level that is too high might reduce stock prices of companies with American operations because of the loss of credibility.

26. November 2009 at 06:51

123, I agree the new Japanese government is reckless, they are relying on fiscal stimulus, which is madness for Japan.

You said;

“In a nutshell, at 1987 top market multiple on expected 1989 operating earnings was close to 12.”

I don’t follow this at all. 1989 was a very strong boom year. I would expect earnings to have been close to optimistic forecasts. Was I wrong?

123#2, Ideally I prefer a bit of “catchup” first, but I’d gladly take your suggestion as a huge improvement over current policy, because at least it would reduce the chance of future fiascos.

30. November 2009 at 14:05

I agree about Japan. But Phelps might fear that any kind of additional stimulus in America would decrease real asset prices. Mutual fund flows support this as since Marche there were outflows from domestic equity funds and there were strong inflows to international stockmarket mutual funds.

In 1987 before the crash markets were expecting strong earnings growth for the next two years, as there was huge rally. In 1989 actual earnings were so strong that they probably exceeded the most optimistic forecasts of 1987.

Not only would it reduce the chance of future fiascos, but it would also help with the current fiasco by reducing macro uncertainty for the next two years.

1. December 2009 at 08:58