Is it 1985-86 again?

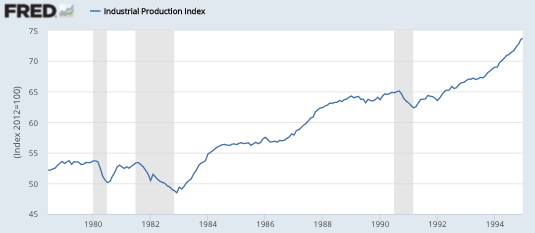

See if this sounds familiar. Halfway through a long expansion, industrial production levels off, after years of rapid growth. This is blamed on two factors, declining oil prices and a strong dollar. I could be describing the past year, or I could be describing 1985-86:

Notice how industrial production leveled off for a couple years, before resuming its rise:

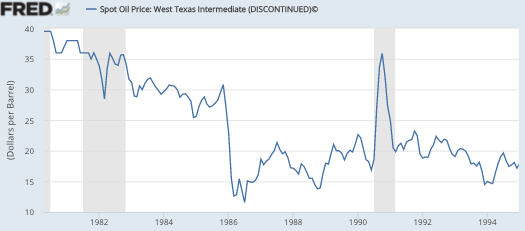

And here is the oil price, which fell gradually in the 1982-85 period and then plunged in 1985-86:

And here is the oil price, which fell gradually in the 1982-85 period and then plunged in 1985-86:

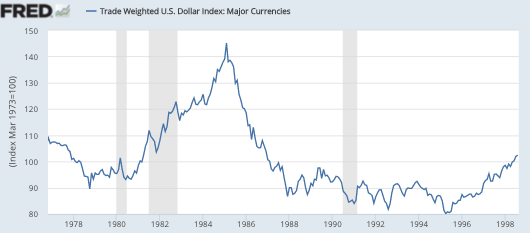

And here is the trade-weighted dollar, which soared in value, and then plunged:

My hunch is that the dollar was more important than oil. Tight money led to a slowdown in NGDP growth and a strong dollar. NGDP growth (year over year) slowed from 12.4% in 1984 Q1, to only 4.9% 1986 Q4. Eventually the Fed eased policy, and NGDP accelerated. The 1980s boom resumed. It actually eased a bit too much in the late 1980s, which set up the 1990-91 recession.

Does this mean that history will repeat? No. But it’s an interesting comparison.

PS. While writing this I forget that Caroline Baum made a similar observation in her book “Just What I Said“, where she pointed out:

This isn’t the first time that a change in oil prices has been regarded as a tax increase or tax cut and anointed with the ability to help or hinder economic growth. Time-trip back to early 1986, when oil prices plunged to $10 a barrel in April from $30 at the end of 1985. This was hailed as good news – a tax cut! – for consumers, which was guaranteed to boost US economic growth.

It didn’t turn out that way. Following the plunge in oil prices, gross domestic product growth slipped to an anemic 1.7% in the second quarter of 1986 . . .

Ah, recall the days when 1.7% RGDP growth was anemic, not above trend.

Tags:

2. February 2016 at 12:35

“It actually eased a bit too much in the late 1980s, which set up the 1990-91 recession.”

Wait. So too much easing can cause a recession? How? I’ve never seen you talk about that.

I remember you saying that too tight money can lower the wicksellian rate, but never that too _easy_ money can.

2. February 2016 at 13:55

Maurizio,

Too much easing, tends to eventually generate an opposite response (boom to bust) on the part of central bankers which can cause a recession.

http://monetaryequivalence.blogspot.com/2016/02/once-and-far-away-inflation-was-not.html

2. February 2016 at 14:46

Maurizio, Becky is right. Inflation rose in the late 1980s, and the Fed tightened to control it, which led to the recession.

2. February 2016 at 15:21

What is the origin of the “oil prices are like a tax” analogy?

It seems to be linked to an idea that the consumer is the only important dynamic in the economy and what should be good for consumer is good for everybody. It just isn’t true.

The consumer isn’t particularly dynamic.

2. February 2016 at 15:23

Scott,

Totally agree with you that the dollar is more important than oil. Yet, do we really believe the conditions are ripe for another Plaza Accord?

To be clear – it is not obvious to me that the dollar weakening post-Plaza was due to monetary policy (US rates fell but so did Bundesbank and BOJ). There was little explicit talk during the Accord about using monetary policy as the primary tool to weaken the dollar.

I am not claiming that sterilized intervention has been effective in post-Plaza interventions nor that it is credible today – merely that we may take for granted that we were lucky in it working out with Plaza, and that generating a similar halt of a dollar rally will be much more difficult today.

As of now, you might think this concern is overblown given that EURUSD and USDJPY rates have been stable for a year – but the locus of depreciation has shifted towards emerging markets – where depreciation reflects causes (e.g. loss of confidence in assets) which are deflationary. If China depreciates – and this depreciation so that it is not expansionary because it is accompanied by financial distress – this could set off a new wave of the dollar rally.

Does the Fed have the ability to loosen monetary conditions sufficiently to halt such a rally? I am skeptical – but as I imagine you would argue, at the very least it could signal that it is abandoning its desire to raise rates further.

2. February 2016 at 17:22

Preston Caldwell: love your name btw.

Today the Fed can also engage in QE while cutting IOER.

My favorite idea is quantitative easing married to FICA tax cuts. Currently it is not legal to have the Fed transfer the purchased bonds into the Social Security trust fund, but it should be.

A similar idea would be to cut the marginal income tax rates, but from the bottom rather than the top, married to aggressive QE.

Both of these tax cuts would have the additional benefit of encouraging participation in the labor force.

2. February 2016 at 17:49

Maurizo, welcome to Scott’s world, where yes, central bankers can cause recession by tightening or by loosening. Like Ragu(TM) spaghetti sauce, Scott’s NGDPLT can advertise “it’s in there”. Like the French say, a man that loves everything loves nothing.

@sssumner: please explain your views on the Plaza Accord of 1985. Did it not affect the dollar? Here is the Wikipedia link to “refresh your memory”: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plaza_Accord (” Most of this devaluation was due to the $10 billion spent by the participating central banks.”). Note: I’m not saying the Plaza Accord did anything much (money is neutral) but wish your views.

2. February 2016 at 17:59

Readers: notice Maurizo asks a specific question upstream, and neither Becky Hargrove nor Scott Sumner give an adequate answer as to how *easy* money leads to recession. Specifically, Sumner answers how tight money can lead to recession (it cannot, money is neutral, but we’re talking about the monetarist construct in his mind), and Hargrove’s post also goes to 80s style tight-money policies by the Fed to combat inflation. Once again, hand-waving by the MM crowd.

2. February 2016 at 18:25

Ray,

A recession is a short term technicality which is not to be confused with a longer term change in economic conditions. When a short cycle of relatively easy money takes the form of credit with excess demand on nominal income, the recession is the adjustment period.

2. February 2016 at 19:52

@Becky – your clarification is disingenuous. What is the time lag for your theory? If you wait long enough, any expansion will, eventually, turn into a recession. On Wall Street they say, correctly, that being early is the same thing as being wrong.

2. February 2016 at 20:01

Yep, and today’s collapse in the high yield bond sector is the same as the collapse of Continental Illinois in 1984 thanks to the awful energy loans it acquired from Penn Square Bank.

3. February 2016 at 09:27

[…] During 1985/6, declining oil prices and a rapidly rising dollar also led to Industrial Production slump. This did not turn into a recession. There is a great piece on this here. […]

3. February 2016 at 11:36

Preston, You are right that the Plaza Accord had little effect. But monetary policy does have a significant impact on exchange rates.

The Fed should not target exchange rates, they should target NGDP.

JP. Nice comparison.

3. February 2016 at 12:10

Ray,

The funny thing is how you constantly claim both that money is neutral and that it is “a little” non-neutral and then act as if these two ideas are consistent.

3. February 2016 at 21:06

@ Cliff, 3. February 2016 at 12:10 who says: “Ray, The funny thing is how you constantly claim both that money is neutral and that it is “a little” non-neutral and then act as if these two ideas are consistent.”

They are consistent: a little non-neutral is 3.2% to 13.2% change, out of 100%, on a range of economic variables (including GDP), for the numerous Fed policy shocks between 1959-2001, the subject of Bernanke et al’s 2002 FAVAR paper. This range is embarrassingly low. It’s so low, I’ve seen other papers that try and prove Bernanke et al was too conservative in their vector autoregression, and instead of negative and positive values they should take the absolute value (which is clearly data manipulation to make Fed policy shocks seem more important than they are, but I digress). In short, MM in the field are embarrassed by Bernanke’s 2002 FAVAR paper (Sumner himself has said he won’t read it). It’s as if somebody wrote a book about the numerous inconsistencies in the Bible (after all it was written by several authors in different times who could not coordinate their narratives), and Sumner, the High Priest of monetarism, has banned reading of this book.

So yes, a ‘little’ non-neutral is the same as neutral and is understood as such even by Sumner.

4. February 2016 at 13:53

@sumner

“Maurizio, Becky is right. Inflation rose in the late 1980s, and the Fed tightened to control it, which led to the recession.”

So, in your view, too easy money can cause a recession, but only when it causes inflation?

Suppose there is a positive supply shock. With constant money, prices would tend to go down. Now suppose the central bank tries to stabilize prices by printing money. It prevents prices from falling. Those prices would otherwise have fallen. This means the Fed is keeping rates *below* the wicksellian rate. But nobody realizes it, because there is no visible inflation (as the positive supply shock has offset that). In your view, this situation would not cause any problems? It cannot cause a recession?

4. February 2016 at 14:09

Maurizio, If easy money causes excessively fast NGDP growth, then you get a recession when NGDP growth later slows down.

4. February 2016 at 14:23

And if easy money does *not* cause excessively fast NGDP growth (but still the Fed rate is below the wicksellian rate)?

(As I said, that situation can arise when there is a positive supply shock.)

Thanks

4. February 2016 at 14:47

Sorry, forget my last comment, it does not make sense. I now see that NGDP targeting does *not* prevent prices from falling in the presence of a positive supply shock. And therefore Fed rates would *not* be below the wicksellian rate. NGDP is so superior to inflation targeting!