How would an RBC economist criticize the Musical Chairs model?

I define monetary policy in terms of NGDP growth. So tight money occurs when NGDP (or expectations of NGDP) are falling. I also claim that tight money causes most recessions. Some commenters argue this is a tautology. That complaint is actually really stupid. Just think about Zimbabwe, where RGDP plunged as NGDP rose by zillions of a percent. But it’s also an unintentional compliment, as we’ll see.

I frequently point out that the unemployment rate is strongly correlated with the ratio of wages to NGDP. Some people argue that this is a tautology. That’s actually a somewhat more reasonable complaint, although it’s not accurate. I say reasonable, because a slightly different version of the “musical chairs model” (MCM) would be a tautology. This version:

1/employment (in hours) = W/Aggregate nominal labor income.

I replaced unemployment with 1/employment (in hours), and I replaced NGDP with total labor compensation, which is well over half of NGDP, and highly correlated with NGDP.

So what’s going on here? Is this a model or a tautology? And if it is a model, how do we falsify it?

Here it would be helpful to think about how a real business cycle (RBC) economist, AKA “new classical” economist, would criticize the MCM, if one of them actually took the time to examine my pathetic little model.

They’d clearly accept the fact that NGDP and RGDP growth are highly correlated in the US, and that unemployment is highly correlated with W/NGDP. That’s not the issue. The issue is the policy counterfactual. We observe that NGDP is often more volatile than W, especially during periods like 2008-09, where NGDP suddenly fell by 3%, or roughly 8% below trend, and wage growth only slowed very slightly. So W/NGDP rose sharply, as did unemployment.

My counterfactual is that had NGDP kept growing at 5% in 2008-09, then RGDP would have also kept growing (although it would have slowed slightly for supply-side reasons) and I claim that wages would have continued growing at about 4%. An RBCer would not agree. In their view the counterfactual result would be high inflation and high nominal wage growth, indeed wages soaring at perhaps 10%/year, or something like that. And because wages would have soared by 10%, the stable 5% NGDP growth would lead to 5% fewer hours worked, and the unemployment rate would soar from 5% to 10%. RBCers don’t believe than nominal shocks have real effects. The Great Recession was caused by real factors, in their view.

The math fits, but how plausible is that counterfactual? And keep in mind, BTW, this is the ONLY possible counterfactual to my claim that stable NGDP growth would have maintained high employment in 2008-09, (or at least that stable growth in nominal aggregate labor income would have worked, if you want to be picky.) Even if you are not a RBCer, but blame it on “reallocation”, this HAS TO BE your theory. For the RBCers to be right:

1. Wages must be highly flexible, and that flexibility is cleverly hidden by Fed policies that, de facto, keep equilibrium nominal wage growth fairly stable.

2. It must be true that with a 5% NGDP growth counterfactual, wage growth would soar much higher in a period of fast rising unemployment like 2008-09, all because, well because fast rising wages are mathematically required to produce the big drop in hours worked that the RBCers insist is the “equilibrium” outcome of some mysterious hard to identify technology shock that causes workers to want to take long vacations. Or something like that.

Can you tell that I don’t find the RBCers counterfactual to be particularly plausible?

Other possible flaws in the musical chairs model? There really aren’t any. When we get to the policy implications, you can certainly question my claim that:

NGDP = stance of monetary policy,

or that the Fed is capable of stabilizing NGDP growth at 5%, or ask whether fiscal policy is needed too. But those policy issues are entirely separate; here I’m just trying to figure out what causes business cycles.

And basically it’s fluctuations in W/NGDP. Which are mostly caused by NGDP shocks. Period, end of story. It’s a really ugly model, and kinda stupid. I wish it weren’t true. But it’s also incredibly robust, just unbelievably robust. Unlike New Keynesians who utilize the Phillips Curve, I can go to sleep at night with serene confidence that I won’t wake up to Bob Murphy or Arnold Kling, or anyone else having some sort of empirical evidence that refutes the model. At best someone might find an episode where it doesn’t fit it quite as well as usual.

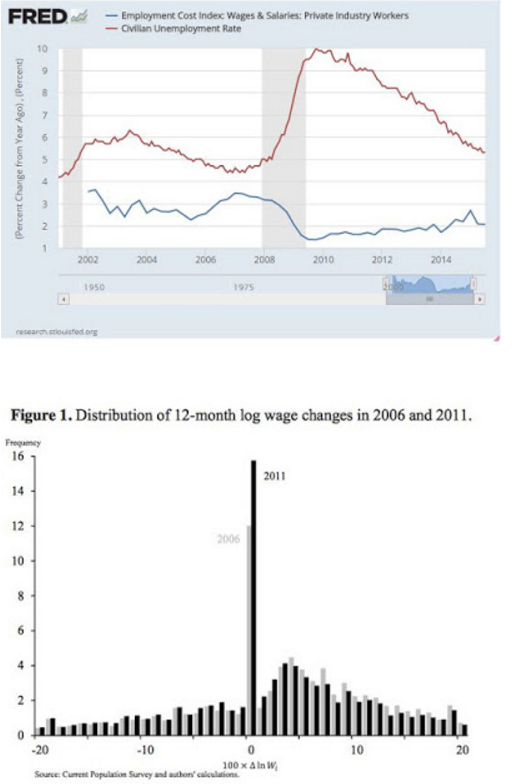

The more interesting question is whether the rest of the profession should take this seriously as a model. I’m too close to give an objective answer. Take a look at these graphs, in a blog post by “Robert“:

Now take a look at the bottom graph. See that spike at zero? The RBC model predicts no spike there at all, because there in no money illusion allowed in the RBC model. So immediately we know that the RBC model is wrong. But all models are wrong, even mine. The real question is how wrong. Maybe they are wrong in assuming no wage stickiness, but in fact there’s only a small amount of wage stickiness, and the RBC model is almost true.

Fair enough. But then they need to convince the rest of the profession on empirical grounds. And go back and read my points #1 and #2 above. Good luck convincing the rest of the profession that those counterfactuals are even remotely plausible.

If we can dismiss the RBC critique of the musical chairs model (which no one has made, AFAIK, but it’s the critique that would be made, by anyone who believed the RBC model) then what’s left for me to defend? Mostly monetary policy.

So let’s say we agree that NGDP shocks cause recessions. OK, that’s not very controversial; indeed it’s pretty much Keynes’s General Theory (I’ll do a post soon explaining why the General Theory is basically the musical chairs model.) So I can’t really claim to have invented anything here. But somehow we’ve drifted away from the General Theory, which focused on NGDP and average hourly wages and employment, to NK models that focus on interest rates and inflation and output. And that’s obscured Keynes’s musical chairs model. Instead of using NGDP shocks to explain employment fluctuations, we use interest rates and government output and technology shocks and price shocks to explain output. It all becomes very confusing, when in fact demand-side recessions are very simple—not enough NGDP to pay the workers.

Maybe if we had an NGDP futures market we could start thinking of NGDP as a policy choice for the central bank, a tool, a lever, and then the musical chairs model would be right in front of us, staring us in the face. Unavoidable.

No matter how hard you try to focus on something else like price stickiness or technology or investment shocks or whatever, W/NGDP is right there, right in front of you. It’s the sine qua non of demand side macroeconomics. If the causation doesn’t go from NGDP, to W/NGDP, to employment, then the RBCers are right. And they ain’t right.

PS. Robert relied on this paper by Mary Daly and Bart Hobijn.

Tags:

11. November 2015 at 06:58

All economic models are tautologies. This is why Communism looks so good on paper.

11. November 2015 at 07:03

Do you think “musical chairs” is the right analogy? Do people play it anymore? Does anyone under 40 know what we are talking about? These analogies are meant to be about things everyone knows about. I think we need a new one. What is the social media/internet equivalent?

Also, when I remember (long, long ago) actually playing the game, the music always seemed much faster as the chairs disappeared. Maybe it was just the excitement of it all? Hey ho.

11. November 2015 at 07:17

Scott,

I noticed that Ted Cruz said that the Fed tightened monetary conditions in Q3 2008. I was surprised and impressed, even if some of his other views on monetary policy are mistaken.

11. November 2015 at 07:48

Cecchetti and Schoenholtz want Japan to go and SIN (Support Inflation Now!) some more;

http://www.moneyandbanking.com/commentary/2015/11/9/learning-from-japan-its-hard-to-end-a-deflation

———–quote———–

Finally, the BoJ knows that – on current plans – the nation’s consumption tax will rise in April 2017 by a further 2 percentage points to 10%. So far, each prior increase of that tax has been followed by a sizable drop in real GDP. With that in mind, there seems relatively little risk to price stability over the medium term if inflation in Japan were to temporarily overshoot the central bank’s 2% target.

One response to all of this is to reiterate the advice some people have given since the deflation started in the 1990s: engineer an exchange rate depreciation. While this was surely sound advice then, Japan’s effective exchange rate already has depreciated by roughly 25% over the past two years with only a small inflation pickup.

So, as the MPC meets over the coming quarters, we suspect that it will be increasingly clear to its members that current policy is inadequate to secure the 2% inflation target over the next two years, just as it was inadequate to reach the target over the past two years. Assuming, as we do, that Governor Kuroda and his colleagues are resolved to rectify this, it is natural to expect them to expand QQE in an effort to increase nominal aggregate demand (with the result that the value of the yen could decline even more). And, if they think as we do, then only a very large further expansion will have much chance of success.

———–endquote———–

11. November 2015 at 08:06

I didn’t have much success looking at this sort of regression in levels (like unemployment regressed against W/NGDP). I found a little more success when regressing YoY differences, but the biggest improvement was switching variables. I/NGDP and C/NGDP both individually and together worked better than W/NGDP. By itself I/C worked better than any of the others individually.

But this doesn’t really tell me anything I don’t already know. If investment is growing faster than consumption, it doesn’t surprise me that unemployment will be falling.

Including more variables provides the best fit in a variety of situations. But the analysis doesn’t exactly point to any of these being the end all be all determinant of business cycles.

11. November 2015 at 08:29

This is fine as far as it goes, but is there any reason to think that preventing NGDP fluctuations is possible?

11. November 2015 at 08:32

“It all becomes very confusing, when in fact demand-side recessions are very simple—not enough NGDP to pay the workers.”

It would add: “not enough NGDP to pay the workers and debts”. My feeling is a good model would take both wage and debt nominal rigidity into account.

11. November 2015 at 08:46

Concerning the debt vs wage nominal rigidity, I don’t have a good feel for the magnitude of the effect of each. In both cases, they lead to a coordination problem (i.e. a demand-side recession). When ngdp drops, firms and people fall into default, which hits consumption and hiring pretty hard.

Is that effect smaller or larger than the effect of the wage rigidity (also, one could imagine that one might cause the other; workers have fixed debt payments, and cannot afford a pay cut without defaulting on debt, leading to some wage stickiness).

11. November 2015 at 08:48

Great stuff.

Hey Scott, one thing that bugged me about the Republican debate last night. Everyone agrees that banks were bailed out, and the big banks were the worst offenders. This is definitely what the audience wanted to hear.

Were banks bailed out? I thought TARP turned a profit. Sounds like a liquidity/confidence crisis that past, and taxpayers were made whole.

Also, what about Canada and its five big banks and no crisis?

Thoughts?

11. November 2015 at 09:12

Modern-day equivalents of musical chairs: Game of Thrones?

Professor Sumner, would it make you happy if politicians, the media, and people on the street only talked about the economy in terms of “aggregate wages”, “price levels”, “gross domestic product”, etc and never used the terms “inflation” and “interest rates”? Are those ways of thinking mutually exclusive i.e. talking about both at the same time can confuse the issue since they’re not “speaking the same language”?

And can you point to me to posts you or others have made which you feel support the claim that “the Fed is capable of stabilizing NGDP growth at 5%”? I think this is the sticking point for me, I accept W/NGDP as a fairly straightforward framework for explaining business cycles, but I’m not convinced we can actually dictate NGDP through monetary policy alone. For example, how would an NGDP futures market actually affect NGDP?

11. November 2015 at 09:20

Some holes:

The big one! The Fed is always capable of maintaining 5% NGDP growth. Sumner says yes! but this is hardly “settled science.”

Monetary policy operates without a lag. Again the bulk of the profession is not on the same side as our professor.

NGDP can be accurately forecasted. In the current state of affairs, we don’t know last quarter’s NGDP until well into the current quarter.

If only we had an NGDP futures market. We don’t.

The government should subsidize such a market. The fact that the government is subsidizing it will pollute the signal you hope to get from it.

1/employment (in hours) = W/Aggregate nominal labor income.

or

wages * employment (hours) = Labor income

What about non-hourly employment? What about variable compensation?

Is cyclicality an unmitigated bad? In a world with constantly evolving technology, new tech will replace old tech and over time entire industries will rise and be destroyed and replaced. This is creative destruction. Even with constant RGDP growth, there will be regional recessions. The business cycle cannot be entirely repealed.

Constant NGDP growth may mitigate some of the pain, but I think you need to develop this side of your argument.

11. November 2015 at 10:49

Hi Scott,

Just to be clear, what some of us think is a tautology is saying:

“Tight money leads to lower expected future NGDP growth. I don’t think that can be disputed.”

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=30702

And then saying in the present post:

“I define monetary policy in terms of NGDP growth. So tight money occurs when NGDP (or expectations of NGDP) are falling.”

If tight money *is defined by* lower expected NGDP growth, then tight money doesn’t *lead to* (i.e. cause) lower expected NGDP growth. It *is* lower expected NGDP growth.

I have no problem with the presentation of the first paragraph, its logic is impeccable. (The converse of “tight money implies recession” is “not tight money implies not recession”, and the converse of a statement is not always true … as shown by Zimbabwe.) But you do tend to go back and forth between the definition ‘tight money is falling expected NGDP’ and the causal relationship ‘tight money causes falling expected NGDP’. So e.g. falling NGDP expectations before the 2008 recession is not evidence of tight money — it is defined to be tight money.

11. November 2015 at 10:59

@Prof. Sumner

If I am not wrong, Keynes explicitly defined his “liquidity preference” effect in terms of speculators selling bonds, putting downward pressure on prices and upwared pressure on rates…

11. November 2015 at 13:45

Just a personal opinion – you are trying to use rational arguments against emotions.

Of course the data doesn’t fit RBC models. But that doesn’t stop some people from supporting them.

Why ? Because the conclusions that derive from their models appeal to their adherents on an emotional level. And the conclusions that derive from a “musical chairs” model offend them, on an emotional level.

11. November 2015 at 14:23

A quintessential RBCer gets it wrong:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2014/05/22/because-they-ignore-monetary-policy-rbc-theorists-think-its-always-due-to-a-supply-shock/

11. November 2015 at 15:32

This is a simple enough empirical question: what happened to Indonesian employment and unemployment in 1997-8? If no data is available for Indonesia, maybe we can look at Mexico or some other part of Latin America. Maybe Israel.

Also, great comment, John Hall. Very poor comment, Daniel.

“Monetary policy operates without a lag. Again the bulk of the profession is not on the same side as our professor.”

-Actually, the profession is on the same side as our professor, but that’s because our professor takes both sides of the issue: see his comments regarding Trichet in the “Nice Guys Finish in the Middle of the Pack” post.

11. November 2015 at 15:45

Excellent blogging.

Candidate Cruz says the price of gold is stable. You know, within a 50% band over any two-year period.

11. November 2015 at 17:47

Oh, lo and behold: unemployment data exist for Indonesia, and it appears that unemployment dropped during it’s depression. It was very different in Mexico 1994, though.

11. November 2015 at 17:47

*its depression

11. November 2015 at 18:19

Sumner: “Here it would be helpful to think about how a real business cycle (RBC) economist, AKA “new classical” economist, would criticize the MCM, if one of them actually took the time to examine my pathetic little model.” – pathetic, indeed. Why not invite a RBC economist as a guest post commentator instead of setting up a strawman? Because he might rip your strawman to shreds?

As for the spike at 0% wage growth, it proves very little. Since inflation is so low, near zero, it doesn’t pay to adjust wages by firing people (i.e., a wage cut) if wages are a bit too high. Thus, any ‘stickiness’ of wages occurs at low inflation, not high, due to inertia. The opposite of what Sumner imagines (that you can profit from sticky wages with high inflation).

11. November 2015 at 19:22

Dan, If I say my theory is that your comments are moronic, is that a tautology?

James, Yes, they still play that sort of game.

W. Peden, That is surprising.

11. November 2015 at 19:31

Patrick, Check out my new Econlog post.

Max, Just peg the price of NGDP futures, worst case is that it fails and I get rich.

LK, Sticky wages cause unemployment, and sticky debts cause financial crises.

Brian, It’s debatable as to whether they were bailed out, but the real problem was the smaller bank depositors, who were bailed out by FDIC.

Kyle, I’d encourage you to look at my two Mercatus papers, on NGDP targeting, and NGDP future targeting,

Doug, I’d encourage you to reread the post, It wasn’t about what causes NGDP to change.

11. November 2015 at 19:45

Jason, I don’t recall the context. Perhaps I meant that no matter how one defines tight money, it reduces NGDP growth. Thus suppose someone claims that a Fed interest rates increase today means tighter money than no increase. My claim is then that it also reduces expected NGDP growth.

Or perhaps the context was that I was claiming tight money causes falling NGDP, and the Fed can control NGDP.

11. November 2015 at 20:24

Scott,

Regarding the RBC counterfactual — I’m not sure they’d agree your counterfactual exists. They say the recession was caused by real factors and NGDP can’t keep going at 5% unless the real factors that caused the recession didn’t exist. That is to say in the counterfactual, there wouldn’t be a 10% spike in wages (or any other changes in the economy) because nothing happens in the counterfactual where NGDP keeps going.

Basically, you have to say that NGDP keeps going at 5% *and* there is a recession (which implies that inflation must have increased). But the RBC counterfactual to constant 5% NGDP growth is no recession, not other changes.

Since the RBC theory is a bit tautological — there has to be some way for it to be consistent with data 🙂

12. November 2015 at 06:21

Off-topic

The BoE came out with a paper back in September on market-based indicators of inflation expectations. Mentions a similar issue that Sumner has brought up several times: the inflation indicator the central bank is targeting is different from the one used in financial products.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/288214249/The-informational-content-of-market-based-measures-of-inflation-expectations-derived-from-government-bonds-and-inflation-swaps-in-the-United-Kingdom

12. November 2015 at 08:42

Jason Smith rips Sumner apart, and Sumner does not even recall what his own post meant, when referenced by Smith with a link to this blog. That’s lazy thinking by Sumner, but we’ve come to expect that.

12. November 2015 at 09:10

off-topic

Prof. Sumner, you probably are familiar with this work http://www.centerforfinancialstability.org/amfm/Divisia_Sep15.pdf , what do you think of that? It seems that Prof. Barnett adjusts money supply in order to account “moneyness” of some of the agregates. It looks to me that he is created an index that in fact adjusts for money demand. Maybe that is useful somehow.

12. November 2015 at 09:17

‘Patrick, Check out my new Econlog post.’

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2015/11/could_gramm_lea.html

Very well done, Scott. Especially your answer in the comments; ‘Bad banking policies create bad monetary policies, and bad monetary policies create banking turmoil.’

In a nutshell, that’s why Gramm, Leach, Bliley would have prevented the crisis in the first place.

12. November 2015 at 10:30

In the comments to Scott’s Econlog post, ‘Emerson’ mentions the report to congress mandated by Dodd-Frank that is undoubtedly the spur to the Fed, and their press release last Friday;

http://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/fsoc/studies-reports/Documents/Co%20co%20study%5B2%5D.pdf

This is interesting;

‘Insurance companies in the United States have issued instruments with characteristics similar to contingent capital. Insurance companies have used these types of instruments to facilitate raising new equity following a catastrophic event that requires them to pay large amounts in claims. One arrangement involves an option to issue surplus notes upon the occurrence of extreme event losses that exceed a predetermined threshold.4 Another involves an equity put option that enables insurers with catastrophic loss exposure to issue new preferred or convertible preferred stock following a natural catastrophe. These transactions can help insurers during periods of financial stress, in addition to absorbing losses.’

12. November 2015 at 11:19

From the same report;

————-quote————-

Some advocates of contingent capital would design the trigger mechanism so that it would be activated during severe macroeconomic conditions, or when financial system stress is very high. The goals of such trigger mechanisms may be to mitigate and shorten a systemic crisis, to stabilize financial markets, or to reduce the contraction

of credit. The focus is on the condition of the financial system or the economy as a whole, rather than on the condition of the issuer of the instrument.

Loss absorption. Because historically severe macroeconomic conditions and material stress in financial conditions have occurred infrequently, this triggering mechanism would be expected to cause conversions infrequently. For this reason, an instrument with a macroeconomic or systemic trigger would likely be priced more like debt than equity. A lower cost of contingent

capital instruments would incentivize the issuer to fund itself more with such instruments and less with debt.

If the macroeconomic or systemic trigger is calibrated correctly, loss absorption capacity for the financial system would be increased during crisis conditions. With more capital funding for large banks and other issuers of contingent capital instruments, the probability and severity of asset fire sales and the potential for damaging runs by debt holders and counterparties could be reduced. For example, a distressed institution may face a relatively reduced need to sell assets due to the earlier conversion of a contingent capital instrument.

However, contingent capital instruments requiring conversion and creating loss-absorption capacity only based on macroeconomic or systemic triggers would not necessarily increase loss absorption when the issuer incurs a large, idiosyncratic loss. This problem could be addressed by using a dual trigger that would trigger conversion upon the earlier to occur of a macroeconomic/systemic trigger and a firm-specific trigger event.

————endquote————

12. November 2015 at 13:20

Oh heck, I just couldn’t resist temptation;

http://hisstoryisbunk.blogspot.com/2015/11/the-sumner-also-rises-to-task.html

12. November 2015 at 13:51

When will CATO release the video of this event???

http://www.cato.org/events/33rd-annual-monetary-conference/schedule

12. November 2015 at 15:15

“I define monetary policy in terms of NGDP growth. So tight money occurs when NGDP (or expectations of NGDP) are falling. I also claim that tight money causes most recessions. Some commenters argue this is a tautology. That complaint is actually really stupid. Just think about Zimbabwe, where RGDP plunged as NGDP rose by zillions of a percent. But it’s also an unintentional compliment, as we’ll see.”

What I have seen from the MM camp are arguments of the form “I define monetary policy and recessions in terms of NGDP” in one sentence, and then maybe the day after I see statements like “Recessions are caused by NGDP falling.”

That is a tautology, and pointing that out is not only not stupid, but is itself pointing out a stupidity.

It is not an unintentional compliment by the way. It is an unintentional career destroyer. But I digress.

“I frequently point out that the unemployment rate is strongly correlated with the ratio of wages to NGDP. Some people argue that this is a tautology. That’s actually a somewhat more reasonable complaint, although it’s not accurate.”

It is not a tautology. It is a reversal of causation. A misunderstanding of correlation. I display of ignorance on praxeological necessity.

Wage payments logically, and temporally, precede NGDP. NGDP is spending on capital goods and consumer goods and services. But capital goods and consumer goods must first be produced if they are to be sold, and part of the production process is labor, which is paid and expensed.

Wage payments are not equivalent to revenues. Spending on consumer goods and services is not spending on labor. John Stuart Mill pointed out about 150 years ago that “Demand for commodities is not demand for labor.”

If NGDP goes up or down, then this does not cause wage payments to go up or down. Wage payments have already been paid by the time NGDP occurs. That is to say, wage payments have already gone up or down by the time NGDP goes up or down. Now of course wage payments and NGDP are in a sense concurrent, but that is only because of a monetary illusion created by looking only at aggregates. Sure, wage payments at company A are taking place at the same time revenues arerevenuesarned by company A. But the revenues company A earns today are for goods and services produced and offered that required labor already utilized. The revenues a firm gets today are not to pay the wages today. The wages yesterday were paid to help produce what is offered for sale today.

Almost all of what constitutes NGDP was financed by prior productive expenditures, particularly for labor.

If NGDP plunges, then that is caused by a prior plunge in productive spending.

So the question to answer is why would any significant decline in investment in one company, or, where it is easier to notice empirically, in one whole industry, not be accompanied by a rise in investment in another industry or industries, given that the companies have the money to invest? That decision is what causes NGDP to fall.

The cause is of course discoordination between firms, or in general between production processes, that was brought about by prior inflation.

Central banks “fighting” deflation are acting counterproductively.

One does not have to offer any alternative monetary policy by pointing out the failure of ALL monetary policy. Anyone who says otherwise is merely politicizing, not engaging in economics, nor any search for better truth or understanding of the world.

12. November 2015 at 17:19

@MF: “What I have seen from the MM camp are arguments of the form “I define monetary policy and recessions in terms of NGDP””

Liar. We can’t help what you imagine in your head. But this statement is simply not true. Please locate a specific cite with an MM claim that recessions are defined in terms of NGDP. You really don’t understand the first thing about MM macro theory, do you?

“Wage payments logically, and temporally, precede NGDP.”

False. Cash holding preferences can change radically over time, thus changing NGDP without (immediately) impacting (or being caused by) wage payments at all.

“If NGDP goes up or down, then this does not cause wage payments to go up or down.”

False. Wage payments must be financed by NGDP. It is not possible to keep wage payments unchanged (over the long-term) if there are dramatic NGDP changes.

“If NGDP plunges, then that is caused by a prior plunge in productive spending.”

NGDP is definitionally equivalent to spending. It’s not “caused” by a plunge in spending. It is a plunge in spending.

12. November 2015 at 22:31

Scott,

I’m not trolling you (right now at least), I’m asking a serious question. Have you written on how you view the value in a currency having a predictable purchasing power?

For example, suppose the Fed enacted a policy where it maintained a constant CPI, with level targeting (i.e. no random walk). This would make the PPM in the year 2030 much more predictable than under your plan. But, you would say there would be more and deeper recessions under this approach.

So in your mind is there even a tradeoff here, or is there no downside to the PPM being more unpredictable in your regime than some others?

13. November 2015 at 07:04

I think an Old Keynesian for example might trivially grant the validity of the model whilst denying its usefulness. They would view the nature of the variables and the causation between them differently. They would grant that falling NGDP with respect to a sticky price or wage level would almost certainly be accompanied by falling employment. But they wouldn’t see it as meaningful to say that your policy remedy would simply be “to stabilize the path of NGDP”; and this would be a conceptual/theoretical difference, and not just a policy one. And correct me if I’m wrong but I think that’s closer to how most mainstream economists see it as well, whatever New Keynesian textbooks they may or may not have read. To them prices and output are separate things, and stabilizing output during a recession is the whole problem. If you succeed, then you will also have saved unemployment, and then it’s not hard for them to grant that wages or prices won’t fall to offset the rise in output, so that “trivially” NGDP (which is simply what you get when you multiply prices and output) has also remained stable. And then the equation is satisfied, but to them still doesn’t mean much.

13. November 2015 at 07:41

@Saturos – you are right, Fiscal (Keynes) and Monetary (Friedman) policy are flip sides of the same coin. They depend on similar priors, such as sticky wages and money non-neutrality, as well as money illusion. All three of these things are largely false. See this excellent rebuttal of Sumner: http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/11/my-macroeconomic-framework-circa-2015.html

Further, as MF notes on different grounds, Sumner makes this logical howler, after pointing out in hyperinflation, RGDP and NGDP are uncorrelated (or negatively correlated) he then states: “[Real Biz Cycle economists] clearly accept [NOT! – RL] the fact that NGDP and RGDP growth are highly correlated in the US [In the US indeed: A RULE OF THUMB-AKIN TO FRIEDMAN’S RULE OF THUMB ABOUT 3% INCREASE IN MONEY SUPPLY IS ALL THAT IS NEEDED–RL], and that unemployment is highly correlated with W/NGDP. That’s not the issue” – but it is the issue. NGDP = RGDP + inflation, AFTER THE FACT (that is, ex post, when the end of the year is up). Before the fact, ex ante, NGDP and RGDP, like in Zimbabwe and elsewhere, are uncorrelated. High inflation (nor low inflation, nor any particular inflation) does not influence RGDP. Inflation is (if caused by supply side factors or structural factors) sometimes even uncorrelated with NGDP, see Japan for the last two decades.

When will Sumner ever learn? Never. But I hope the rest of you learn.

@Don Gheddis – you did not rebut any of MF’s points, but you did a good character attack. That’s your forte little man.

13. November 2015 at 12:21

I think monetary policy matters a lot more relative those other factors he mentions than Tyler thinks, and also that monetary policy is effective more frequently and more belatedly at reducing unemployment. That said I also find his combination of the Sumner model (“musical chairs”) with Mortensen-Pissarides to be both clever and plausible (they did get a Nobel for it), and Tyler knows more literature than almost anybody. Would be keen to hear Scott’s take.

14. November 2015 at 09:12

Scott, don’t you agree though that nominal wages are far more sticky downwards than upwards? Isn’t that a defence for the RBCer?

14. November 2015 at 16:45

Jason, You said:

“They say the recession was caused by real factors and NGDP can’t keep going at 5% unless the real factors that caused the recession didn’t exist.”

No, that’s not their view, and RBC theory (which I don’t agree with) is not in any way “tautological.”

Thanks Garrett.

Jose, I don’t know enough about that to have an intelligent opinion. But I’m skeptical that that measure of M is useful.

Thanks Patrick.

Bob, No tradeoff, because as Keynes and I showed the price level is a vague concept, not clearly defined. It’s not very useful, indeed it’s not even clear what we mean by “stable prices”, when the product mix is changing so rapidly. NGDP targeting means the value of money is stable in terms of the share of NGDP that can be purchased with a given dollar.

Saturos, You said:

“But they wouldn’t see it as meaningful to say that your policy remedy would simply be “to stabilize the path of NGDP”; and this would be a conceptual/theoretical difference, and not just a policy one.”

I disagree, that’s basically what Keynes calls for–stabilize AD. The key difference is that Keynesians don’t agree with my claim that the Fed can stabilize NGDP.

You said:

“I think that’s closer to how most mainstream economists see it as well, whatever New Keynesian textbooks they may or may not have read. To them prices and output are separate things, and stabilizing output during a recession is the whole problem.”

Not at all, the Taylor Rule (which is a NK policy rule) tries to stabilize a weighted average of prices and output. (Albeit not exactly NGDP.)

You said:

“don’t you agree though that nominal wages are far more sticky downwards than upwards? Isn’t that a defence for the RBCer?”

Yes, and no. And I wouldn’t say “far more”, I’d say “somewhat more”

24. August 2016 at 07:35

[…] a simple “musical chairs” model of unemployment. He describes that model here and here. Essentially the idea is that the total number of jobs in the economy can be approximated by […]