Fracking drives manufacturing

[Before starting, let me recommend a new Sebastian Edwards paper discussing the effectiveness of MMT-style policies in Latin America. I have a new post at Econlog.]

Last year, I did a post over at Econlog speculating that cycles in the price of oil led to cycles in fracking activity, which led to cycles in manufacturing employment growth.

Seven months later, the fracking/manufacturing part of the hypothesis is looking increasingly plausible. For various reasons, fracking activity has slowed in recent months. In this case, however, the slowdown is not due to weak oil prices, and experts predict a pickup later in the year:

Schlumberger CEO Paul Kibsgaard told analysts and investors last week that his company is seeing a slowing-down of activity in the U.S. shale plays over the first four months of 2019. “North America land activity is set for lower investments with a likely downward adjustment to the current production growth outlook,” Kibsgaard said, “the higher cost of capital, lower borrowing capacity and investors looking for increased returns suggest that future E&P investments will likely be at levels dictated by free cash flow. We, therefore, see land E&P investment in North America down 10% in 2019. ”

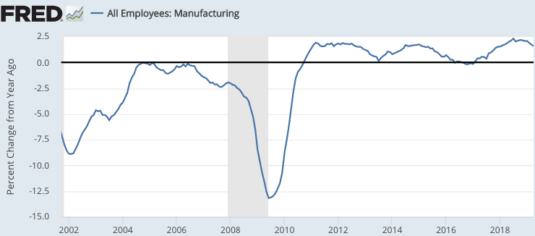

Overall, employment growth in 2019 continues to be strong, running at 205,000/month, only slightly below 2018 boom levels. But manufacturing job growth is slowing more rapidly, with growth especially anemic over the past three months. Year-over-year data shows the rate of manufacturing job growth slowing from a peak of 2.3% in July 2018 to 1.6%, and I expect a further decline.

Notice that there was also a manufacturing jobs boom during the 2014 fracking boom.

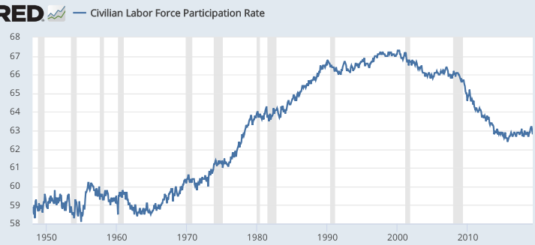

Labor force participation in April was 62.8%, exactly the same as 5 years ago. But that’s actually good news, as the retirement of boomers was expected to lead to further declines. On the other hand, I doubt we’ll get back to the levels of the late 1990s; there are too many demographic headwinds:

The 3.6% unemployment rate is consistent with what we are seeing in other similar developed economies. Relatively “neoliberal” economies are seeing unemployment fall to rates not seen since the 1960s. What makes the US stand out is that productivity numbers have also been pretty good (unlike places like the UK.)

Job growth in the US is also helped by a recent surge in immigration. Overall, a very good jobs report. It shows that manufacturing is not the key to strong employment gains, but fracking is the key to strong manufacturing jobs gains.

PS. Speaking of the UK, I predict their next election will feature Trump vs. Sanders, err, I mean Boris Johnson vs. Jeremy Corbyn. If the Liberal Democrats can’t do well against those two clowns, it’s time to close up shop. If the Brits had any sense, they’d make Rory Stewart their PM. But only after Brexit is resolved—that’s one of those problems that would destroy any leader.

Tags:

3. May 2019 at 11:02

[…] At MoneyIllusion I have a follow-up on last year’s post discussing the link between fracking and manufacturing […]

3. May 2019 at 11:26

Scott,

One observation.

I’m involved with a manufacturing company. Investment is pretty closely correlated to free cash flow. (We loved the tax cut.) A lot of investment replaces older machinery with new machinery that produces more and requires less people. I suspect this is pretty similar at other companies. It takes fairly big increases in output to generate increased employment in manufacturing.

3. May 2019 at 12:13

Scott, I think you’re right about the oil-manufacturing link. The Penn Wharton Budget Model had a post earlier this year which agreed and had some nice charts illustrating the point:

http://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2018/12/14/the-price-of-oil-is-now-a-key-driver-of-business-investment

3. May 2019 at 13:30

dtoh, You said:

“It takes fairly big increases in output to generate increased employment in manufacturing.”

This is where the business perspective may be misleading. Business decisions are “lumpy” while aggregate data is smooth. Thus 9/10 of businesses may not increase capital and employment with rising output, but 1/10 might do so a great deal (say an entirely new plant.) At the aggregate level that get smoothed out, and the link between employment and output is pretty tight, once one adjusts for the fact that productivity gains mean output will tend to rise faster than employment.

On the other hand, during a cyclical recovery your point has more validity, as more than 9/10 firms will be operating with slack. The key issue is what happens to the average amount of excess capacity in industry as output increases. For long term growth, there is no change, on average. For a cyclical recovery the slack does diminish. But even there employment tracks output fairly well.

I used to argue with my dean on this point. He said one more student at Bentley did not increase our costs, because lots of classes had empty seats. He was wrong about costs. Adding new classes is a “lumpy” decision.

Stoneybatter, Thanks. I hope they call it “the Sumner hypothesis”. 🙂

3. May 2019 at 14:18

Scott,

I’m not sure it’s as lumpy as you think. I know that’s the classic model, but output and capacity have a lot less to do with capex than they used to. It obviously depends on how capital intensive the manufacturer is, but most decent sized manufacturing firms in the US have huge long lists of potential investments where the IRR will exceed the cost of capital. Some of the investment is driven by energy or raw material savings, but a lot of it is driven by getting the same output with fewer workers. The pace of investment is driven much more by cash flow than by demand, and the annual variation in capex for any given firm is not that great. I think a lot of firms would double or triple their capex if they had the cash even if they had no expectation of higher demand.

I’m sure employment tracks output, but my point is that because of the productivity gains that can be had, it takes a big jump in output to generate a small jump in employment. The goal of capex in manufacturing is very often too reduce the labor force.

3. May 2019 at 15:22

If these gains in productivity are sustainable, it provides some evidence that I’ve been correct in suspecting much of the slowdown was demand-related. While the tax cuts and perhaps some deregulation have provided some oomph to RGDP, there’s also been some offset due to the trade skirmishes.

I feel okay today seeing many economists on Twitter making fun of themselves for saying we’d reached NAIRU roughly two years ago

But, am I right for the right reasons, if I am? I think the answer is at least partly yes. My peusdo-multiple equilibrium perspective is still not supported strongly, notwithstanding a few recent data points. Need much more data.

3. May 2019 at 15:23

“What’s more, unit-labor costs declined 0.9% in the first quarter. Over the past year unit-labor costs — how much it costs to make each product — have risen a scant 0.1% to mark the smallest increase since 2013.”

Tight labor markets! Tight labor markets! Will Robinson, Danger Danger!

Gadzooks! I wonder how many trillions of dollars of lost output can be racked up to those macroeconomists who cowered before the Inflation Boogeyman.

As we speak, labor costs are a drag on the Fed’s putative 2% inflation target. And labor force participation rates are rising again.

3. May 2019 at 17:17

Interesting how anti-capitalism is in vogue, but we are currently seeing more gains go from capital and top of labor distribution to rest of labor distribution.

Both sides make fun of the “neoliberal” view, but truly we just need to:

1. Have a robust monetary policy against NGDP declines.

2. Fix real issues in health care and finance.

Unfortunately, there is still work needed on both of these. I *still* have little confidence in the Fed handling another zero lower bound.

3. May 2019 at 17:57

Matthew Waters:

Agreed, but a really big one is property zoning.

As Mercatus scholar Kevin Erdmann points out, in many cities the ceiling on new housing construction results in household income gains essentially being sucked into the pockets of property owners. No real household income gains.

This is most evident on Hong Kong, but applies all along the US West Coast too.

There is probably no fix for this. The propertied-financial class is powerful, as are the NIMBYs. The libertarians are in a full-throated roar against rent control…but, you know, property zoning probably needs reform, of an undefined nature at an undefined future date.

AOC in the White House someday? She will win the West Coast….

3. May 2019 at 21:36

[…] At MoneyIllusion I have a follow-up on last year’s post discussing the link between fracking and manufacturing […]

4. May 2019 at 04:01

Scott wrote: ” What makes the US stand out is that productivity numbers have also been pretty good (unlike places like the UK.)”

But one should consider this:

“The OECD report says that if the UK measured productivity in a comparable way to the US, the gap between the two countries would reduce from 24% to 16%. In comparison with France, the gap fell from 19% to 11% and in relation to Germany from 22% to 14%”

4. May 2019 at 04:04

Scott wrote: “What makes the US stand out is that productivity numbers have also been pretty good (unlike places like the UK.)”

But one should consider this:

“The OECD report says that if the UK measured productivity in a comparable way to the US, the gap between the two countries would reduce from 24% to 16%. In comparison with France, the gap fell from 19% to 11% and in relation to Germany from 22% to 14%.”

4. May 2019 at 07:21

@benjamin

Curious… how big a problem do you think property zoning is. Erdmann suggests that in the US the average percent of income going to housing has not risen.

Does it have an impact on aggregate output or does it just impact wealth/income distribution?

4. May 2019 at 17:09

Dtoh

well, think Hong Kong. People now pay a fortune to live in 120-square-foot nanoflat. On paper the average Hong Kong resident makes plenty of money. In real life they live in more-cramped quarters than they did two generations ago.

As Kevin Erdmann can tell you, the way the US government measures housing costs and inflation, and the fraction of household income that is consumed by housing costs is fraught with difficulty.

And to be sure, the high housing costs along the coasts are somewhat offset by low housing costs in the interior. A young couple starting out in life in Missouri might actually do better than a couple generations ago.

But ask Kevin Erdmann on his blog. I am sure he will respond, and politely, to your inquiries.

4. May 2019 at 17:20

MMT is okay and useful. More clear about resource allocation for social choices. They are not saying only expansive monetary policy.

4. May 2019 at 22:00

“What makes the US stand out is that productivity numbers have also been pretty good (unlike places like the UK.)”

No. It’s not that America’s are good; it’s that the rest of the First world’s is awful.

5. May 2019 at 05:49

Benjamin

So the reason I ask the question (and I don’t know the answer) is because I think the situation you describe (while increasing inequality) also transfers money to wealthier individuals who have a higher marginal propensity to invest which in theory should result in higher growth.

Also, another issue is whether land is used efficiently. This is somewhat orthogonal to the ownership question and relates more to regulation, zoning, and tenant rights.

5. May 2019 at 08:02

dtoh, Certainly when manufacturing output rise X%, then employment rises by considerably less than X%. But that’s perfectly consistent with what I wrote in the post.

5. May 2019 at 08:34

Scott,

Yes, I understand. That’s what I was trying to say also albeit poorly.

5. May 2019 at 16:13

Scott, this post agrees with your basic thesis, but puts it in a political divides/culture war context.

https://chicagoboyz.net/archives/59712.html

5. May 2019 at 19:17

Dtoh– Actually, some posit the situation Erdmann describes only results and more and more capital being soaked up by real estate. The picture of London and Great Britain. Adair Turner has written intelligently about this.

I would say that I agree with Turner, but then I remember that in macroeconomics no one is ever wrong or right.

5. May 2019 at 21:19

Fracking actually is a good example of why the UK is not as productive as the US. Essentially the UK is a more centralized Government, so policies get set nationally for the most restrictive areas. in the US the states have a lot more freedom to set policies locally, so Texas can do fracking. Imagine if US national policies for oil and gas extraction were set by the people in NY city.

6. May 2019 at 04:52

If Boris Johnson is the UK version of Trump, that doesn’t reflect well on the USA. Johnson is actually a fairly erudite fellow. I saw a debate on YouTube between Johnson and Mary Beard on Greece vs. Rome as a model for our time. Boris acquitted himself pretty well. I’d bet Trump couldn’t even sit in a chair and watch that debate for 5 minutes, let alone participate.

Not sure how that translates to politics, but the British “boor” seems a few cuts above his American counterpart.

6. May 2019 at 10:26

ChrisA, Good example. Indeed the failure of Europe to cash in on fracking speaks volumes as to the difference between the two economic systems.

Brian, Exactly right. He’s Trumpian by British standards, but positively Churchillian by modern US standards.

I might even vote for him over Corbyn, whereas I’d never vote for Trump over Sanders.

7. May 2019 at 03:22

From the Bank of International Settlements:

Jens Weidmann: Monetary and economic policy challenges

Speech by Dr Jens Weidmann, President of the Deutsche Bundesbank and Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Bank for International Settlements, before the Industrie-Club Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, 2 May 2019.

Central bank speech | 07 May 2019

by Jens Weidmann

….First, US firms have successfully raised their mark-ups over their marginal costs sharply: according to a widely discussed study, from an average of 21% in 1980 to 61% in 2016.4 Increasing market concentration has been identified as a key factor in this expansion of margins. The OECD estimates that a 1% increase in the largest firms’ market share will raise the price mark-up by 1.1% to 1.7%.5

Second, the labour income share, i.e. workers’ share in national income, has dropped in the United States. Around one-third of the total decline in the services sector can be attributed to the increase in market concentration.6

Third, productivity gains have suffered: if price mark-ups attributable to market power are eliminated, according to one calculation this could increase what is known as total factor productivity in the United States by up to 20%.7

—30—

Got that?

https://www.bis.org/review/r190507a.htm

14. May 2019 at 06:56

Hi Scott

Can you provide a link to last year’s EconLog that references the fracking cycle post.

Thanks

14. May 2019 at 10:01

Frank, Sorry about that, it’s there now.