Evaluating German NGDP growth

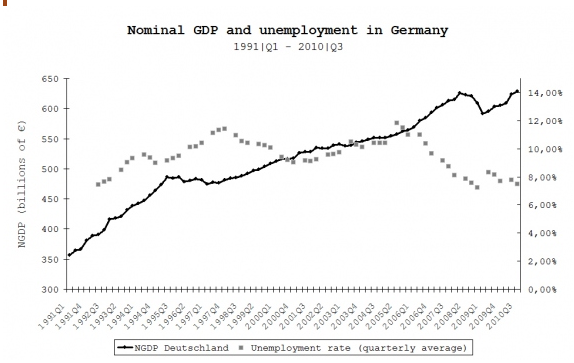

Kantoos has a German language blog that shares my quasi-monetarist perspective. He recently sent me an english version of a post that has this graph showing German NGDP and unemployment:

You’ll notice that German NGDP growth is less stable than US growth, even before the recent recession. Here are a few observations, with the caveat that I am not an expert on Germany.

Smaller economies tend to have more unstable real and nominal growth. Although Germany is big in absolute terms, it is small relative to the US. For instance, Germany had 8% real growth in the second quarter, and the slightly smaller UK economy just reported negative 0.5% growth in the 4th quarter. US RGDP growth doesn’t tend to show such big swings.

Because Germany is part of the eurozone, nominal and real GDP movements are more independent than in the US. Thus suppose the ECB targets 2% inflation. In that case fast growing eurozone members will have higher NGDP growth than slower growing members, even without higher inflation. In fact, inflation is usually higher in faster-growing economies.

After the reunification boom, Germany had a difficult period from 1994 to 2006. Notice that nominal growth was slow and unemployment was in the 10% to 12% range. It is reported that during this period Germany went through a painful process of adjusting nominal wages downward, to reflect the slow NGDP growth (and inflation, which was lower than elsewhere in the EU.) Ironically, during this period ECB policy was arguably too tight for Germany, and too easy for fast-growing Spain and Ireland.

Here’s what I found most interesting. It seems to me that this graph might help explain Germany’s relatively good performance during this recession. Notice that NGDP growth picked up sharply in 2006, and then NGDP fell sharply in late 2008. Current levels of German NGDP look very similar to what would have occurred if you extended the fairly straight trend line from 1997-2006. My hypothesis is that the wage restraint practiced by German unions during the difficult years of high unemployment may have carried over into the 2006-08 boom. If so, wages may be closer to equilibrium than in the US, where current NGDP is far below the trend line of the past few decades.

This is a very tentative hypothesis. It is dangerous to look for trend lines, as the eye tends to spot patterns that aren’t really stable. In addition, I am relying on news reports about German wages, not hard data. I would add that the low unemployment rate overstates Germany’s success. Output has fallen sharply in Germany, and many workers had to accept shorter hours. Still most observers think that Germany has recently done better than other major developed economies, and the temporary nature of the 2006-08 NGDP bulge may partly explain why.

Germany could probably benefit from a bit faster NGDP growth, but from a “level targeting” perspective they may be closer to long run equilibrium than most other developed countries.

PS. Interested readers should also read the Kantoos post, as he covers other topics that I am not qualified to discuss.

Tags: Germany

26. January 2011 at 11:19

This graph seems rather strange. According to the IMF Germany has a nominal GDP of about €2.5trillion, not approximately €600billion as indicated here.

Also the graph depicts almost linear growth in NGDP for 20 years, whilst this is possible NGDP growth is of course usually exponential.

26. January 2011 at 11:27

Scott,

I am going to put aside your argument against looking at trend lines for a little bit, but it still be valid. post-unification I do not really see very much instability here, I see the unification boom, then the slight correction from it, and then from 1997 onward I see one, basically straight line going all the way to the present. The only real deviation from trend was the housing bubble. There is a slight upward shiting of the curve near the end, which I do not know enough about Germany’s economy to be able to explain. However, as a whole, this looks like something that were I writing a text book of Austrian theory I would include. There is a long period of normal growth, interrupted by an unsustainable boom and then corrected for by the inevitable bust.

26. January 2011 at 13:47

@Robbie: I think these are non-annualized, quarterly NGDP figures.

In addition to wages, I’ve read that German real-estate prices and household-debt levels were the most stable in the Eurozone during the “boomlet” from 2005-2008.

It looks like it might just be possible that an economy with wages and certain prices that are also sticky-upwards in a boom is more robust than one in which they rise quickly in the bubble but are sticky-downwards in the pop. Counter-cyclical policy should work in both directions. Seems to me like good NGDP level targeting would do this pretty much automatically.

But politically, in the US, you’d get folks immediately shouting bloody murder if wages don’t keep pace with growth during a boom. What the political economy of the sustainability of a regime like that? It works in Germany, but here? I wonder.

26. January 2011 at 16:24

“an economy with wages and certain prices that are also sticky-upwards in a boom is more robust”

Sticky upward wages and prices, once the economy has gone above potential output, increase the tendency for an economy to overshoot potential output to an unsustainable level if NGDP grows faster than potential output plus the rate of inflation at which potential output is reached. And that is what happens in actual market economies. I do not see how that makes an economy more robust since it will boom the boom.

If they became flexible upwards at potential output, this would keep output from reaching an unsustainable level above potential output, since the excessive NGDP growth would go into price and wage increases instead. Unfortunately, since they will be sticky downwards, once they have gone up the economy is stuck with them in the short run, which can be painfully long.

26. January 2011 at 16:39

[…] should have done this graph before, because now the implications are clearer. As Scott Sumner suggests in a post, this shows that NGDP level targeting is working and that the ECB policy was exactly right for […]

26. January 2011 at 17:25

I think its useful to look at Kantoos’ entire post as well as the one that precedes it when judging the trend of German NGDP. So let me rewind completely and show you why I reach somewhat different conclusions than either Scott or Kantoos (my opinion is somewhat between the two).

Go back to this post and look at Kantoos’ graph of Eurozone NGDP:

http://kantoos.wordpress.com/2011/01/17/extrem-kontraktive-geldpolitik-ist-symmetrisch/

Notice how easy it is to place the trendline and what it reveals about the deviation in trend starting in late 2008. Notice also the very slight deviation below trend around 2005.

Now go and look at what Kantoos does with trendlines in the above graph in his post (I won’t post a link because Scott’s already done it). He places three trendlines, one for the “reunification” trend (7.1%), one for the “adjustment” trend (2.1%) and one for the 2006-2008 trend (about 4%). He implicitly draws the conclusion that Germany is well below trend based on the last rather steep trendline.

Scott reaches a rather different conclusion choosing to view the 2006-2008 trend as an aberration. Thus he decides that Germany currently may not be too far from long run equilibrium.

I think it’s useful to remind oneself that Germany is part of a currency union, and effectively has been so since 1998. When I saw the graph of Eurozone NGDP and the graph of German NGDP I instantly wondered what the graphs of the NGDPs of other Eurozone members looked like.

Well, as you might imagine, and as Scott suggested, the smaller members generally show relatively large deviations from trend. But what was interesting is that the graphs of the NGDP of France, Italy and Spain, which collectively account for nearly 50% of Eurozone NGDP, are each about as smooth as a baby’s bottom through early 2008. Their NGDPs behave exactly as you would expect, given relatively large nations and a minimally competent central bank.

So putting all this together, it’s quite clear that Germany is the outlier in that it is a relatively large nation showing large deviations from Eurozone trend. Which brings me back to the graph of Eurozone NGDP. Remember that slight deviation below trend at around 2005? Well that can be accounted for almost entirely by Germany’s relatively slow NGDP growth around that time.

So where would I place the German NGDP trendline? I wouldn’t break it at 2005:4Q/2006:Q1 like Kantoos. And I wouldn’t place it below that apparent “bubble” like Scott. I would place it in such a way that it most closely matches the facts of the overall Eurozone NGDP graph. In other words it would place it tangent to the peak of German NGDP in early 2008.

Are there other facts to make me think this is appropriate? Well, let me list a few:

1) Real wages in Germany are lower now than they were 20 years ago at the time of reunification.

2) RGDP growth over 1998-2007 averaged 1.6%, lower than any other Eurozone country save Italy.

3) German unemployment was double digit from April 2004 through May 2006, peaking at 10.8% in March 2005.

4) Most importantly, since the recession began the average number of hours per worker in Germany has fallen about 4% and GDP per hour worked (productivity) has fallen about 3%. This is largely attributable to worksharing and this is the main reason why unemployment has remained more or less constant since early 2008. This looks even worse if you consider that it is more reasonable to expect productivity to increase over a three year period.

In short, my evaluation of German NGDP growth is that it is about as bad as the rest of the Eurozone core (8-9% below trend), which means it is about the same as the US. It only looks good if you compare it to the Eurozone periphery. Time to sack Trichet and get the ECB to bring the whole Eurozone back to its long run NGDP trend.

P.S. I now see that Kantoos has come over to agreeing with Scott which now puts me all on my own.

26. January 2011 at 19:28

Robbie, Those are quarterly numbers.

aaron, You are confusing NGDP and real GDP. There is no such thing as an unsustainable boom in NGDP. It can rise at a billion percent.

Indy, Good point about Germany having no housing bubble. I’d guess that the boom was driven by strong growth in developing countries, which buy lots of German capital goods. That also partly explains their strong recovery.

Full Employment Hawk, Maybe, but I think Indy is considering a case where the boom is temporary. If so, it might be better to never have wages raised, then to have them raised but unable to fall. I don’t have strong views on that, as I’m not sure this asymmetry in wage flexibility exists.

Mark, I think Germany is probably a bit below trend, but not that far. I’m puzzled by the figures you cite, which suggest German RGDP has fallen 7% from peak. I thought the German recovery had been fairly strong, and Kantoos shows German hours bouncing back. Are your figures up to date?

Otherwise I think you make a pretty strong case.

26. January 2011 at 20:13

Indy @ Scott: German house prices move at about the rate of inflation, with a bit of a drop in the national index after unification when the poorer quality East German stock was added in. Since the Federal German Constitution includes a “right to build” supply responds to demand smoothly, so they lack quantity controls creating price effects. Also, German population growth is non-existent, so they only have any household shrinkage to push demand for housing.

Not that population growth has much explanatory value, as we can see if we add in Ireland, UK and Spain all of which have housing price boom and busts, and Texas, which has booming population growth and no boom-and-bust in house prices. But I am a bit of a bore, insisting that quantity controls have price effects even in housing markets.

26. January 2011 at 22:35

Scott,

It turns out you’re partially right about item 4). It was based on a six month old OECD article. Germany’s Federal Statistical Office does not make it easy to find seasonally adjusted labor statistics (they must exist because Kantoos’ data appears seasonally adjusted) so I compared like quarter on like quarter. Hours per worker in 2010 Q3 was only 0.4% below 2008 Q3. (In contrast it was off 4.7% yoy on 2009 Q2.) Since total employment was up 0.5% in 2010 Q3 over 2008 Q3 this of course means total hours are up 0.1% over two years ago.

Seasonally adjusted RGDP is easily found at Eurostat and in the third quarter it was still 1.8% below its previous peak in 2008 Q1. Putting the two facts together implies that GDP per hour worked is still about 2% lower than it was 2.5 years ago. And conservatively assuming a trend RGDP growth rate of only 1.6% annually, that means that RGDP is *only* about 6% below trend in Germany. So they are doing a little better than I thought.

27. January 2011 at 08:28

Scott,

Thanks to Kantoos I have the seasonally adjusted data. My difficulty stemmed from the fact it is only available in German. (Glücklicherweise meines Wissens in der Ökonomie ist viel besser als meine Fähigkeit, Deutsch zu verstehen.)

In 2010 Q3 employment was up 0.9% over 2008 Q1, Hours per worker were down 0.8%, and total hours were up 0.1%. Thus GDP per hour is down 1.9%.

27. January 2011 at 09:44

New posts on this topic have popped up everywhere. I won’t link because there are just too many of them:

1)Ryan Avent in “How to devalue without devaluing” suggests that the ECB loosen monetary policy such that there is a real appreciation in Germany and real depreciation in the Eurozone periphery.

2)David Beckworth responds in “The ECB is Getting Something Right” by noting that the one thing Germans hate more than Eurozone bailouts is Eurozone inflation.

3)Kantoos has a follow up called “What about real GDP in Germany?” that (IMO) helps illustrate the productivity gap I noted above.

Fascinating if you are a Europhile.

27. January 2011 at 09:54

And I missed the most recent one by Ryan Avent:

“The only thing worse than a suboptimal currency area is a suboptimal central bank to go with it.”

http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2011/01/monetary_policy_1

27. January 2011 at 20:02

Lorenzo, You are still right about quality controls.

Mark, Thanks for that info, it sounds plausible. Yes, I’m surprised how many people have linked to the Kantoos blog. It’s good to see people in Germnay paying attention to the NGDP issue.

28. January 2011 at 22:14

The German unemployment numbers should be comparable to Holland, Denmark and Austria (similar demographics, countries are highly integrated similar taxation levels. But they are quite a bit higher Especially the comparison with Holland is valid that has similar crisis policies aimed at worker retention) and on top of that Holland had a pre-crisis residential construction boom, unlike Germany. I guess that there are structural factors at work not related to policy (Germany has no minimum wage, Holland does). Main culprit: look to the East: complete cities that have been refurbished but where the productive workers have left, like in Rostock, that went from pre-Wende 350.000 to 250.000, whilst losing about half its 25-45 year olds..One of the few places in Western Europe where waitresses and shop assistants tend to be in their late fifties (and very competent). No one will bring work to these people and if they were prepared to move they would have done so long ago..

29. January 2011 at 10:09

Rein, Interesting. That’s something I have also noticed. Germany is often viewed as a great economic success, but is somewhat poorer than neighboring countries like Switzerland, Austria, Holland and Denmark. I think Belgium and France are about equal.

29. January 2011 at 21:36

Scott,

You can spend a lot of time on this! Austria, Holland, Denmark and Belgium are all economies of between 10 and 5% of Germany, in terms of GDP. Germany’s share in EU GDP has declined since 2000 (Eurostat), its small neighbours (and Also Poland and the Czech Republic) have not. The latter two have grown their share. and the former have maintained it. My simple hypothesis is that many sates (for instance NRW is about the same size as Holland and has a very similar profile ) of Germany have done as well or better that the neighbours to the west and all have done worse than Poland.

Simple: integration effects: the first wave was intro-German integration temporarily slowing down cross border (except to the East when the necessary roads etc were built, state firms were privatized etc and once that had happened, these started to grow faster). During the second wave, intro German integration ran out of steam and the process of cross border integration in the West resumed based on location (logistics, clustering), etc. Not only driven by German “pull” locations like the great car production centres) of course. For instance just across the border is the Dutch technology cluster that includes the ASML (the world’s largest maker of chip manufacturing equipment). But Germany as a large country has large tracts where private sector investment is simply disadvantaged as a result of national policy and the labor that sill remains would need to be subsidized or neutralized by benefits. Germany has chosen the latter and is struggling with the result, because, like in Holland, Denmark etc, there are severe shortages of skilled workers in the regions that look more like the small neighbours.

Incidentally, when I browsed through Eurostat, it struck me that the fastest growing non ex-CMEU EU members (by share of total EU output) since 2000 were Greece, Ireland and Spain. Portugal, often considered the next domino was comparable to the German neighbours..

29. January 2011 at 22:10

Rien Huizer,

Poland is the only nation in the EU that did not have a recession and the lesson is simple. Poland was able to follow an independent monetary policy, and it did.

I have absolutely no quarrel with the concept of the Euro. My problem is with how the Euro is currently being managed. Trichet and his successor Weber are an absolute disaster. I could never in good conscience advise my countrymen to adopt the Euro under these circumstances.

30. January 2011 at 06:15

Mark Sadowski,

Fair enough, I did not suggest that the EUR was involved! Although you are right that it may be unwise to join this type of monetary integration just yet. I do not believe Portugal and Greece should have joined, and Ireland should only have done so if the UK had too. And as far as EUR monetary policy is concerned, I believe it does a good job for the highly developed members. The trouble with the EUR for the peripheral countries is that they signed up for a stability pact that would amount to suicide, because there would be a point where rolling over excessive debt caused by accumulated deficits would become problematic and under those circumstances their gvt would have to apply austerity (essentially taking the economy back towards pre-euro trends, writing off ill advised investments and paying off something similar to a national gambling debt. I am exaggerating but I an sure that quite a few German economists would explain this with a “I told you so, ja?” smile..

So, probably Poland would not be truly welcome unless it would have been already well integrated and assimilated -into Germany that is..

30. January 2011 at 07:30

Rien, I have older posts arguing that in the modern world it’s an advantage being small (better governance, less problem with rent seeking.) Of course this doesn’t explain the success of the US, but perhaps it does explain our recent problems.

Thanks for the info on Germany, you obviously know much more about it than I do.

31. January 2011 at 22:24

Rein Huizer,

I always thought it was a mistake for any of the fastest growing countries of Europe to joing the Euro too early. That would include the Baltic States, Ireland, Poland etc. When things stabilize things might be different. The biggest problem is Germany’s antigrowth policy. I guess we are in agreement, except that I view integration and assimilation as being applying to the EU, not Germany.

31. January 2011 at 22:28

Rien,

Pardon me for my finger dislexia.

1. February 2011 at 12:29

John Quiggin has a nice post on current ECB monetary policy and Germany aptly titled “One Size Fits Nobody”:

“Particularly in GDP terms, Germany’s recovery has not been that strong, and an expansion based on exports could easily be derailed by the kind of currency appreciation that would follow an interest rate rise, or even a really credible commitment to hold inflation down. And given the difficulties of handing out explicit haircuts, a modest amount of inflation seems likely to be a low-risk way of easing debt burdens without endangering the (largely German and French, and also UK) banks that hold a lot of the debt.”

http://crookedtimber.org/2011/01/22/one-size-fits-nobody/

1. February 2011 at 16:57

Mark, Thanks for the Quiggen post. I did something like that a year ago.

8. February 2011 at 04:37

[…] NGDP growing steadily from about 2005 to present. The late 2000′s saw above trend growth, Sumner has commented on this, and suggested that this might explain the surprisingly strong RGDP numbers even though nominal GDP […]

13. February 2011 at 19:03

[…] 13, 2011 by admin David Beckworth points to Scott Sumner, who points to Kantoos on the effectiveness of nominal income targeting in Germany. Kantoos‘ […]

8. June 2011 at 21:07

“In fact, inflation is usually higher in faster-growing economies.” – No, inflation is higher in economies experiencing a growing money stock.

14. June 2011 at 10:21

Michael, I meant to compare countries within a single currency–the Balassa/samuelson effect.

6. January 2013 at 13:11

[…] Beckworth points to Scott Sumner, who points to Kantoos on the effectiveness of nominal income targeting in Germany. Kantoos‘ […]

28. March 2013 at 14:21

[…] Beckworth points to Scott Sumner, who points to Kantoos on the effectiveness of nominal income targeting in Germany. Kantoos’ […]