Don’t boycott artists

The NYT has an article discussing a London exhibition of paintings by Paul Gauguin:

Is It Time Gauguin Got Canceled?

LONDON — “Is it time to stop looking at Gauguin altogether?”

That’s the startling question visitors hear on the audio guide as they walk through the “Gauguin Portraits” exhibition at the National Gallery in London. . . .

. . . The artist “repeatedly entered into sexual relations with young girls, ‘marrying’ two of them and fathering children,” reads the wall text. “Gauguin undoubtedly exploited his position as a privileged Westerner to make the most of the sexual freedoms available to him.”

How should we judge people who lived in an earlier era? By our standards? By their standards? Indeed, should we make any judgments about their personal life?

I am a utilitarian, so I like to think about the practical value of cultural practices such as “shaming”. How does it make society better off? Does it discourage bad behavior?

When artists are long dead, it’s harder to make a utilitarian argument for boycotting their work. I suppose one could argue that shaming discourages bad behavior, and that even the prospect of future shaming (after death) could encourage artists to behave better, to insure they have a good reputation in posterity.

That seems like a bit of a stretch, especially if the behavior was not seen in the same way when the artist was alive. A French/Peruvian artist living in the 19th century might not have realized that by 2019 the NYT would regard certain types of sexual practices as being more evil when engaged in by “privileged Westerners” than when similar practices were engaged in by native born men. So I’m dubious that the prospect of a future boycott would have deterred Gauguin.

There are also significant costs associated with boycotting artists. Gauguin was an extremely productive artist, producing (in aggregate) paintings worth hundreds of millions, if not billions of dollars. There would be large costs if viewers were deprived of the pleasures associated with viewing this art. Some viewers might find that Gauguin’s personal life in some way tainted the art, which prevented them from enjoying the paintings. But that’s an argument for individuals to avoid viewing the art, not a societal boycott. Where’s the “externality” argument calling for collective action?

Ironically, when I was young, Gauguin’s personal life was considered a plus by people (men?) in the artistic community—he was viewed as a sort of “hippie”, rejecting staid bourgeois values. In the 19th century, his life was seen as scandalous for reasons entirely different from those discussed in the NYT.

There’s also the slippery slope argument against boycotts. Should D.W. Griffith’s films be boycotted because he glorified racism? Should Leni Riefenstahl be boycotted for glorifying Hitler? Should Frida Kahlo be boycotted for glorifying Stalin? Does your answer depend on whether you are on the left or the right? When it comes to politics, even highly intelligent people often hold appallingly ill-founded opinions. Should we cut people some slack because it’s apparently so difficult to think clearly about political issues?

And what about unproven allegations? Many in Hollywood are boycotting Woody Allen due to allegations that were investigated by the authorities and found to be unsubstantiated. Why not let the criminal justice system do its job?

In the end, we might end up not punishing the worst people. Many, many, many famous artists who produced art and literature of incredible beauty and sensitivity were basically cruel jerks in their personal life. But being a mean person doesn’t get you blacklisted, rather you get blacklisted for violating some sort of taboo. In the 17th century, it might have been atheism, then later it might have been homosexuality, then (in the 20th century) the advocacy of fascism and communism. Today it might be racism or sexism. But this is self-indulgence; society is boycotting people based on our current ideological obsessions, not the eternal moral truth that cruelty is the worst thing that humans do.

“The person, I can totally abhor and loathe, but the work is the work,” said Vicente Todolí, who was Tate Modern’s director when it staged a major Gauguin exhibition in 2010, and is now the artistic director of the Pirelli HangarBicocca art foundation in Milan.

“Once an artist creates something, it doesn’t belong to the artist anymore: It belongs to the world,” he said. Otherwise, he cautioned, we would stop reading the anti-Semitic author Louis-Ferdinand Céline, or shun Cervantes and Shakespeare if we found something unsavory about them.

As I utilitarian, I have a hard time justifying that claim. Shaming can deter bad behavior. But so can prisons. And what is the marginal value of shaming in a culture that already has prisons? So perhaps Vicente Todolí is right for the wrong reason. Some artists are deserving of being boycotted, but from a “rules utilitarian” perspective we’d be better off agreeing to a blanket rule analogous to the First Amendment to the US Constitution. No boycotts of artists.

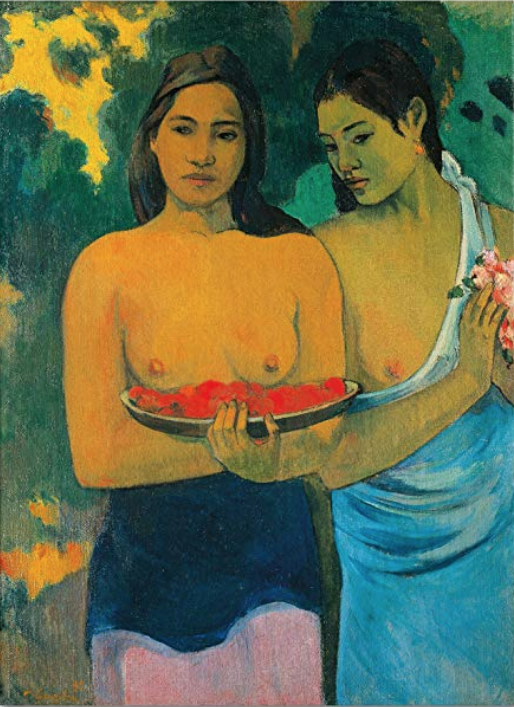

Gauguin may or may not have been evil, but his art is among the few things that make life worth living:

Tags:

21. November 2019 at 13:04

One difference between Gauguin and DW Griffith et al. is that the latters’ art has a much more prominent political message. In that way you can have a more nuanced view of appreciating the craft and historical significance of a work, while at the same time disagreeing with the political message.

Of course merely appreciating a work of art is a different set of considerations than buying a work of art. If Frida Kohlo were alive, I may not want to buy one of her works if I disagree with her message, even if I knew it would appreciate in value. But that is up to the buyers to make their determination of value.

21. November 2019 at 13:13

Controlling the Overton window — i.e. establishing the limits of what it is legitimate to say in public–is how an educated/cultural capital elite seeks to dominate society.

With the collapse of the Christian moral order from the 1960s, the moral grounding space is up for grabs.

Culture war 1.0 (dethroning the Christian moral order) is over. Now it is Culture war 2.0, who gets to dominate society via imposing a new moral order. And just like the Christians did in the C4th and C5th, taking over the bureaucracies is the path to social power. Thus, taking over the bloated administrations is how DIE (Diversity Inclusion Equity) becomes dominant in academe. (Diversity units are not the hired help, they are your moral masters.)

But boycotts, deplatformings, sackings, etc is how the new order is both signalled and imposed.

https://americanmind.org/essays/welcome-to-culture-war-2-0/

22. November 2019 at 07:59

I stopped reading at Woody Allen. The guy married his adopted daughter!

You hurt your whole argument by bringing him into the conversation.

22. November 2019 at 08:40

I love his work. Put an asterisk next to his name and then just enjoy the art. No way am I boycotting him.

22. November 2019 at 12:04

James, I don’t believe that’s accurate. (Someone correct me if I’m wrong.)

22. November 2019 at 13:44

“Soon-Yi Previn is the adopted daughter of actress Mia Farrow and musician André Previn, and the wife of filmmaker Woody Allen.

…

Previn has stated that Woody Allen was never any kind of father figure [to her], and added that she never had any dealings with him during her childhood.

…

Previn married Allen in Venice in 1997. They have adopted two children together. The family resides on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soon-Yi_Previn

So no, what James said seems to be untrue.

By the way, good post overall, Scott.

23. November 2019 at 01:15

Some boycotts may serve a utilitarian purpose but, as Scott lays out well, that doesn’t seem to apply in this case. It seems highly unlikely that artists will be deterred from behavior that they don’t even know will be disapproved of long after their deaths.

Instead, many boycotts/cancellations nowadays are simply acts of expression: people boycott Gauguin as a way of saying, “I disapprove of his sex life,” or “I disapprove of exploitation of young women.” The problem is that viewing Gauguin’s work does not *necessarily have to* convey speech about his sexual behavior. People can view his work without necessarily approving of his sexual behavior or, indeed, even having any knowledge of his sexual behavior. So, rather than unnecessarily tying two things together, it would be better to keep them separate: people that disapprove of Gauguin’s sexual behavior could just say so directly in words, “I disapprove of Gauguin’s sexual behavior,” rather than boycotting, thus allowing people to view and enjoy his work without being misunderstood as approving of such behavior.

Admittedly, in some cases, an artist becomes so closely associated with objectionable behavior that it becomes difficult to keep separate appreciation of the artist’s work from approval of the objectionable behavior. Some people *might* feel that way about Woody Allen due to the widespread publicity about his affair and/or because, as a living person, he can still profit from his work. The difference between the two cases is that, in the Woody Allen case, the association (between artist and objectionable behavior) came first which led people to avoid his work. In the Gauguin case, however, it seems like the boycott is intended at least in part to create an association that doesn’t already exist.

23. November 2019 at 10:01

Isn’t the behavior that “cancel culture” discourages openness?

24. November 2019 at 06:22

Actually Scott – being a Utilitarian means you are encouraging this kind of behaviour. Utilitarianism is a subset of moralism, which means to have a moral position that you believe is correct and then wanting this applied to others, even when they disagree with your moral behaviour. The people who want to “cancel” Gaugin are doing so because they have some moral belief that they want to apply to other people (they are not satisfied with just ignoring him themselves, they want other people to follow their lead). The better answer to this question (as to whether it is right that Gaugin should continue to be showed) is that there is no answer – it is an incoherent question. Right and wrong do not exist despite our desire that they do. Of course some things are abhorrent so a large number of people, like say murder or child abuse, but that is not the same as right and wrong unfortunately.

24. November 2019 at 19:24

I don’t think the urge to “cancel Gaugin” comes from a directly utilitarian place, so I can see how it’s hard to justify that way. I’m very much on the fence about this issue – and I love Gaugin – but I think the cancel argument carries some weight.

First, what Gaugin did was not, by the definitions we use today, just something in his “personal life”. If he had had sex with those girls in today’s world, he would be liable for *public* prosecution; would probably be put on a sex offender’s list; and would have to inform his neighbours every time he moved into a new house. That is to say, it goes beyond the purely personal.

In Roman times, people went to watch gladiators and heretics get torn apart in the arena. We now recognise that that’s gross; and somewhat unhealthy as a society. But the lions they watched were just as majestic as the ones we can watch today on safari; the gladiators may have been sportsmen just as good as today’s tennis players or boxers. That entertainment was bad because it packaged moral horror along with athletic brilliance.

Similarly with Gaugin. The cancel argument isn’t about *him*. It’s about us. It’s saying, don’t allow his artistic brilliance to blind you to the fact that he is packaging moral nastiness with beautiful colours.

Importantly, the motion of “cancelling”, even when successful, doesn’t negate the speaker/painter/artist’s right to do their art. It just says, don’t do it here, on this platform. Gaugin lived; his paintings will live on. But should big museums be advertsing (brilliant) pervs?

I’m a veggie, and I quite like this argument: If you’re not willing to slaughter it yourself, you shouldn’t eat it (acknowledging that many people are willing to slaughter, and respecting their right to eat). Are you willing to spend time in a room with Jeffery Epstein? If not, you shouldn’t consume the products of people like him, including Gaugin.

As I say, I’m not 100% convinced by this yet, but I think it’s a not-inconsiderable argument. And it is certainly not a problem of freedom. No one’s freedom is being compromised.

25. November 2019 at 07:47

The idea that we should give up on something with genuine utility based on the creator/finder/inventor seems crazy to me under certain situations. One wouldn’t ignore a scientific discovery, or talk about how we should base less technology off of it because the inventor was immoral.

I think in art it is complex because for some reason we care so much about the story of the the object rather than the object itself. Prices of art jump when you find out it was made by davinci rather than his pupil for example. It seems quite rational to factor the creator’s morals into this aspect of the experience. That you don’t get lots of galleries filled with high quality replicas (but stated as such) suggests the story part of it dominates.

30. December 2019 at 07:48

[…] Moon and Sixpence is loosely based on the scandalous life of Paul Gauguin. For the 1942 film version, which follows the novel fairly faithfully, the artist […]