Does the New Keynesian model explain Japan? Does it explain Britain?

I’d say the answers are no and no. Here’s Tyler Cowen:

When it comes to Japan and the Japanese lower bound, the empirical evidence seems to show that “standard theory” predicts quite well and the stranger zero bound theories do not predict well. Here is Braun and Korber:

“We show that a prototypical New Keynesian model fit to Japanese data exhibits orthodox dynamics during Japan’s episode with zero interest rates. We then demonstrate that this specification is more consistent with outcomes in Japan than alternative specifications that have unorthodox properties….”

Those same zero bound Keynesian models predict that economies should have quite volatile responses to real shocks, yet they do not:

“We also considered specifications of the model that have larger government purchase multipliers and some which also exhibit unorthodox predictions for the response of output to labor tax and technology shocks. We found that these specifications are difficult to square with the fact that the period of zero interest rates in Japan between 1999 and 2006 was a period of low economic volatility.”

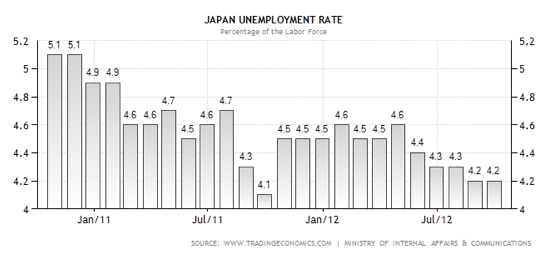

That made me think of 2011, when Japan experienced the largest natural disaster to hit a developed country in my lifetime. A disaster that shut down the entire nuclear power industry for years (an industry that had supplied one fourth of Japan’s electrical power.) A disaster that killed 20,000 people. A disaster that occurred when interest rates were stuck at the zero bound. This graph shows the impact of the March 2011 tsunami on Japanese unemployment:

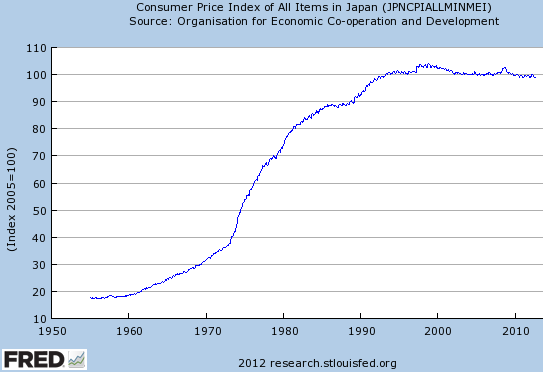

See the effect? Neither do I. The basic problem is that the zero rate models assume that Japanese monetary policy is passive. But it’s not, indeed the Bank of Japan has stabilized the Japanese price level more effectively that any other country in human history. And yes all you Austrian readers, I’m including the gold standard era. Japan’s price level was 100.0 in March 1993, and it’s 99.0 right now, almost 20 years later. The only changes during that period was a jump of a couple percent in the late 1990s when the national sales tax was added, and a tiny rise and fall in 2008 when world oil prices spiked. That’s it.

Because the BOJ is successfully targeting the price level at 100, by raising rates and reducing the monetary base when inflation threatens, and cutting rates back to zero and doing QE when deflation threatens, the NK zero bound models have no applicability to Japan. That’s why real shocks don’t push Japan into a deep recession.

So how about Britain? I’m afraid they don’t work there either. Unlike Japan, The BOE has not been able to hit Britain’s 2% inflation target. Indeed inflation has been accelerating in recent years:

This is why the BOE refrained from taking any steps (such as QE) to stimulate the economy during their last meeting. Does a central bank that refuses to ease because inflation has averaged 3.3% over 5 years face a “liquidity trap?” Keynes would roll on the floor laughing if he were alive today and heard some of the NK explanations for Britain’s current predicament.

BTW, I believe the BOE should be told to ignore inflation and target NGDP, which is why I favor additional monetary stimulus in Britain (and Japan.) But why should anyone expect them to do this when the British government has given them a target that calls for tightening?

If the Cameron government wants more demand, all they have to do is ask for it.

PS. I don’t recall any NK bloggers mocking Merkel’s call for (fiscal) demand stimulus in Germany a few weeks back, but perhaps I missed something that people can point me to. Recall that Germany has been opposed to monetary stimulus from the ECB.

PPS. Sweden is pursuing exactly the same tight money policies as Britain, indeed even tighter. And yet unlike Britain they are not at the zero bound. New Keynesians need to open their eyes and recognize that the zero bound isn’t the fundamental problem; ultra-conservative central banks are the problem.

Tags:

12. November 2012 at 07:39

I know Scott is going to have a laugh at this old one, but it seems to me that the problem here is that more aggregate demand doesn’t solve problems of resource allocation. When you look at the troubled economies of the world you see businesses, especially large banks, representing a large portion of GDP that governments prevent from failure or restructuring. You also see useless real estate projects all over the world in places like Spain, Ireland, or China. You can’t explain much about an economy simply through price indexes. If inflation and NGDP growth drive employment, how come Japan’s unemployment rate is low and Britain’s is higher?

12. November 2012 at 07:46

John, Scott always freely admits that Britain’s problems are predominantly supply-side – but they have big NGDP problems too. As does Japan:

Scott, wouldn’t the Tsunami call for monetary tightening to preserve the price level, deepening the recession?

Also did you see my comment at the bottom of that page? I presented a Sumnerian take on Tyler’s evaluation…

12. November 2012 at 09:24

ssumner:

The basic problem is that the zero rate models assume that Japanese monetary policy is passive. But it’s not, indeed the Bank of Japan has stabilized the Japanese price level more effectively that any other country in human history. And yes all you Austrian readers, I’m including the gold standard era. Japan’s price level was 100.0 in March 1993, and it’s 99.0 right now, almost 20 years later. The only changes during that period was a jump of a couple percent in the late 1990s when the national sales tax was added, and a tiny rise and fall in 2008 when world oil prices spiked.

It’s interesting Sumner defends price levels as coherent concepts when used to promote a positive image of central banking, but then on other days he says price levels are meaningless when used to promote a positive image of NGDP targeting. How can one hold that price levels are meaningless and impossible to measure in one breath, but then say look how awesome the central bank of Japan did, it held the price level constant for 20 years, in another?!

——————————

Gold standard advocates do NOT advocate for the gold standard on the basis of “stable prices.” If prices are less stable in gold, then that’s not a knock against gold. It’s a virtue. It’s a feature, not a bug. Prices should reflect not only relative valuations of goods, but also of the monetary commodity. Resources are scarce, and people’s preferences change.

The ideal of price stability is actually an ideological artifact that dates back to pre-economics-as-a-science times, when theologians and statesmen believed the value of money doesn’t change. “Value” was assumed to be an objective quantity inherent in objects, and money was the measure, the fixed yardstick, of the values of goods and their changes.

The familiar standard of fixed measurement as used in the natural sciences, was haphazardly and unjustifiably imputed into economic science during the Progressive and Post-Fed Act era. Who was the champion of this? Irving Fisher. Fisher revealed his reasoning for why he wanted price stability “management” in his autobiography:

“I became increasingly aware of the imperative need of a stable yardstick of value. I had come into economics from mathematical physics, in which fixed units of measure contribute the essential starting point.” – Stabilised Money, pg 375.

Lunacy. This is the sort of arm chair nonsense that cost Fisher his entire life’s savings when he claimed the Dow reached a “permanent plateau”, right before collapsing.

Economics has been plagued by this unwarranted transfer of methodological approach from the natural sciences ever since. It never occurred to Fisher that maybe there are fundamental differences in the nature of science of physics and of human action. And incredibly, many of today’s economists are carrying that stinky torch like it’s some virtuous idea.

Austrians who advocate for a free market in money, or defend the gold standard from the attacks of the usual suspect, actually do not want to abolish nor minimize price fluctuations. They desire whatever fluctuations would prevail in a free market that would necessarily be a function of marginal utility, i.e. relative preferences, of goods and of money, constrained to private property rights, economic freedom, and profit and loss.

Having said all that, Japan’s 100.0 price level in 1993 and 99.0 twenty years later is nothing compared to the price stability achieved by gold.

There is a rather well known fact that circulates in gold-bug circles: a luxury toga and pair of sandals in ancient Greece cost around one ounce of gold. Today, it a luxury suit and pair of loafers costs around one ounce of gold. That’s 2000 years plus of price stability…for men’s fashion.

But what about more encompassing data? Unfortunately, fiat money has the advantage of having more credible historical data available as compared to pure gold standard economies. So there is definite selection bias. Sumner’s claim is not actually that Japan has had the most stable prices in any country in human history, but rather, that Japan has had a substantial period of price stability out of the sample of countries of which he has credible data.

That is not sufficient for the claim that Japanese prices are the most stable in human history. Not unless you have exhaustive data that stretches back thousands of years.

But even in the sample of available data, Japan 1993-2012 is soundly “beaten” by (often pseudo-standard) gold:

http://i.imgur.com/fN3Q1.png

Look how relatively stable the deflator was from 1790 to 1913, as compared to post 1913.

Now, in the interests of accuracy, I have also lopped off and omitted the post-1913 data, to show the fluctuations pre-1913 in greater detail:

http://i.imgur.com/RQi9w.png

While this seems to be volatile, please note that the two large spikes are periods in which the government moved away from gold, and printed greenbacks and other fiat notes to pay for the wars of 1812 and the Civil War of the 1860s. If you take away those large spikes, and you look at the deflator of the 1830s, then we see that throughout the next 70 years, until 1900, the deflator is unchanged. Imagine no inflation of fiat notes during the 19th century. While it isn’t exactly stable as in zero inflation, it’s 70 years of roughly stable prices.

It is actually quite “unnatural” for there to be ZERO inflation for 20 years. It takes state power to impose something like that. Saying that this is a gotcha against gold is misguided.

Then there is the fact that there is an almost total absence of businessmen and investors voluntarily adopting any sort of tabular standard (in which repayments of debt are corrected in accordance with an agreed-upon index), which suggests a complete lack of merit in compulsory price stabilization schemes anyway, on par with the lack of merit in NGDP futures that are also not being traded now, for obvious reasons (they’re worthless).

12. November 2012 at 11:08

John. The point is not to have “more AD,” it’s to have stable AD growth.

Monetary policy doesn’t affect the natural rate of unemployment, which is much lower in Japan than in Britain.

12. November 2012 at 12:12

You are spot on with Merkel. And might I add that last time I checked ECB refused to cut interest rates from their current 0.75% because “inflation expectations are solidly anchored” or whatever lame excuse they use nowadays? Are we stuck at dreaded “0.75” lower bound here in Europe that leaders call for fiscal stimulus packages?

12. November 2012 at 12:48

Scott: Any thoughts on the Cowen-Krugman discussion of Bond vigilantes?

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2012/11/the-bond-vigilantes-with-a-floating-exchange-rate.html

Very curious what you think.

12. November 2012 at 13:21

Here is another perspective:

“Standard sticky-price models predict that temporary, negative supply shocks are expansionary at the zero lower bound (ZLB) because such shocks lower expected real interest rates and thus stimulate consumption. This paper tests that prediction with an earthquake and oil supply shocks, demonstrating that these shocks are contractionary at the ZLB despite also lowering expected real interest rates. Positive one-year inflation risk premia at the ZLB further indicate that investors want to insure against unanticipated inflation, which is inconsistent with the standard Euler equation framework and suggests that contractionary, negative supply shocks are quantitatively important over this horizon. These facts are rationalized in a model with financial frictions, where negative supply shocks reduce asset prices and net worth — this tightens balance sheet constraints at banks, so that borrowing spreads rise and consumption contracts.”

https://sites.google.com/site/johannesfwieland/

12. November 2012 at 13:37

There’s a simple answer: No.

12. November 2012 at 14:30

Scott, I’m interested in your views on Britain because Australia is heading in a similar direction. Are you saying that if the supply-side is problematic (and taking that as a given), steady NGDP growth should be prioritised over steady growth in prices, even if this leads to higher average inflation?

12. November 2012 at 15:13

And who said positive real growth requires positive inflation?

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=cKK

12. November 2012 at 17:30

First, I’ve read you blog for a while and I’d like to say it’s done a lot to increase my knowledge of economics in a format that educating but still accessible.

My post is only tangentially related to this and more on the topic of inflation targeting in general. I think you have a better understanding than most economists of political realities and the need to choose not necessarily the best policy but the best one with the highest chance of enactment.

Along those lines what would you say to an inflation target that was not set each year but instead determined by exogenous factors, such as say population growth plus productivity growth? This could then be added to a RGDP growth target of 3%, giving us a target of with the advantages of NGDP growth in that it is stable, reliable and economically beneficial, but also determined by pertinent macroeconomic factors, which would give it legitimacy with regular people and makes it more easily defensible against the economically illiterate.

12. November 2012 at 17:45

Rajat, when was the last time Australia had a recession again? Over 20 years ago, right? I’m looking forward to seeing if they can keep the streak alive. Do they have significant supply-side issues? Dutch Disease?

12. November 2012 at 18:33

Rajat,

Australia is the exact inverse of the UK. Here’s yoy CPI and real GDP:

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=96444&category_id=0

If there is an AS shock it’s a positive one.

12. November 2012 at 19:37

Sticky wages tale of the day.

The world is at risk of being forevermore deprived of Twinkies, because Hostess workers won’t take an 8% pay cut to get the company out of bankruptcy.

Oh, think of the children. To never know of Twinkies…

12. November 2012 at 22:04

Mark, nah, that’s just output growth recovering to its natural rate as global demand for our exports stops collapsing. Trend RGDP growth used to be 3.5%. As you can see however, money is too tight – an NGDP growth target would allow CPI/PCE growth to return to 2.5%, so that NGDP growth could return to 7%. A level target would call for even more easing. No wonder unemployment is rising…

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2012-11-08/employment-figures-october/4360574

12. November 2012 at 22:06

Jim Glass, yes, how will we survive when the zombies attack?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h81VGWQip4k

12. November 2012 at 22:13

In fact FRED shows that despite postive CPI growth the price level as a whole is deflating, as NGDP growth dips below RGDP growth: http://research.stlouisfed.org/fredgraph.png?g=cLv

13. November 2012 at 04:57

OK Scott, we really need a post on Krugman:

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2012/11/the-bond-vigilantes-with-a-floating-exchange-rate.html

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2012/11/paul-krugman-does-believe-that-an-attack-of-the-bond-vigilantes-would-be-expansionary.html

And here is Nick Rowe: http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/11/waiting-for-the-bond-vigilantes.html#more

13. November 2012 at 06:08

Rajat, Yes, because inflation doesn’t matter, NGDP growth matters.

Ryan, I’ve argued that’s a good second best as long as it’s:

1. Level targeting

2. Based on long run estimates of RGDP trend growth, which are revised only once a decade or so.

13. November 2012 at 06:10

Saturos, Is that falling resource prices? How are Australian hourly wages doing?

13. November 2012 at 06:41

Saturos,

A rising RGDP rate of growth despite a falling NGDP rate of growth? Again, that has none of the defining features of a negative AS shock, does it?

Also, I can see no trend in unemployment. The rate has been oscillating in a narrow range from 4.9% to 5.4% for over two years now. What they call an increase in unemployment in Australia would be called a statistical anomaly almost anywhere else.

13. November 2012 at 09:08

Well I think that there is always a coherent theory for what has happened in Japan. I find it quite interesting to be honest, together with the decreasing benchmark price in the RE market. I think that Japan itself contains many variables unknown to outsiders and their monetary policy is governed by stability principle more than being expansionary. I think the social relations in Japan can explain to us more than any other economic theory or paradigm.

I´m still with Huntington on the premise that Japan is not a part of the Western world but rather isolated culture. It is different to the current austerity/spending fight in Europe (How to Fight Global Economic Crisis) or the obvious ambiguity of the democratic conservative president Obama in the United States.

13. November 2012 at 09:31

Unsettled Worker:

“I think that Japan itself contains many variables unknown to outsiders and their monetary policy is governed by stability principle more than being expansionary. I think the social relations in Japan can explain to us more than any other economic theory or paradigm.”

Social relations in Japan suddenly shifted in the early 1990s? Because that’s when things went from highly inflationary to zero inflation.

I would think Japanese social relations are subsidiary to economic paradigms if we’re going to explain what happened. I mean, if a “stability principle” is the explanation for post-1990, why wasn’t the same price stability prevalent pre-1990?

13. November 2012 at 11:30

Yes, Scott and Mark, falling resource prices has led to a falling terms of trade, which has caused RGDP to exceed NGDP recently. NGDP is down below 4% when it was 6-7% for most of the last 20 years. True, unemployment has only risen to 5.4% so far, but thanks to a falling participation rate. Non-tradeables CPI inflation remains 4-5%, which seems to be preventing the RBA from cutting interest rates.

13. November 2012 at 11:44

Hourly earnings in Australia are fairly stable at 3.7% year on year, only down a little from previous years (new September qtr data out today). But full-time ‘ordinary time’ earnings (excluding overtime) is down to 3.4% year on year. Again this is well down on recent years (about 5%).

13. November 2012 at 17:46

Rajat, Thanks for that info. That data doesn’t seem too worrisome yet, but obviously if things slipped further it would be a concern.

14. November 2012 at 16:48

[…] 1999 paper on the “self-induced paralysis” of Japanese monetary policy. Amongst many obvious parallels, here’s one I enjoyed. Bernanke’s paper is based in large part around debunking this […]