Does the Fed affect markets? And is the sky blue?

Casey Mulligan starts off a new column as follows:

New research confirms that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy has little effect on a number of financial markets, let alone the wider economy.

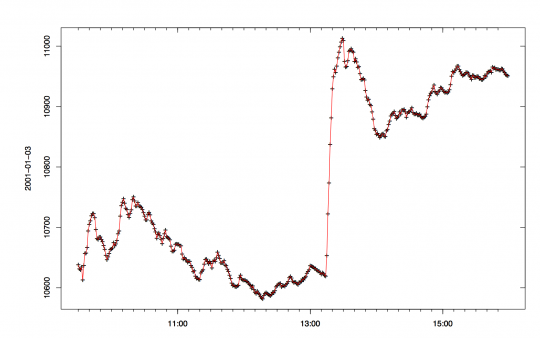

Let’s start with the fact that everyone who works in the financial markets thinks this is nonsense. Of course they also think the EMH is nonsense, and it’s true . . . er . . . truish. But this time they are right. Here’s the market response to the Fed’s unexpectedly large rate cut of January 3, 2001:

I presume this graph shows a futures market in Chicago, central time. Does anyone want to take a wild guess as to what time of day (in Chicago) the Fed makes it’s interest rate announcement? BTW, the more comprehensive S&P rose even more that day, by 5%.

And then there’s September 2007, when another larger than expected Fed rate cut was associated with an immediate rise of several hundred points. And December 2007 when a smaller than expected rate cut was associated with an immediate fall of several hundred points. Funny how the stock market often randomly goes completely nuts at 2:15 EST. Even more amazingly, in the latter two cases the market thought that either a 25 or 50 basis point cut was likely, and using fed funds futures we pretty much know that roughly 5% of US (and world!) stock market wealth hinged on whether the Fed cut rates by 1/4% or 1/2%. That’s a couple of trillion dollars folks. I don’t think many people would regard that as “little effect.”

A question for younger academics who know more about this than I do. What sort of studies show “little effect” on financial markets? The announcement effects are obvious. Are these academics relying on VAR models using quarterly data? As my daughter would say, “I’m confuzzled.”

And that’s ignoring the fact that many monetary shocks don’t even show up in the fed funds market, an issue Mulligan overlooks in the rest of his column.

Yes, Mulligan is a UC economics professor. And yes, Milton Friedman is spinning faster and faster in his grave.

PS. The graph is from a Stefan Klossner paper linked to above. Please tell me if I misspelled his name, I’m not good with German letters.

Tags:

26. July 2012 at 06:30

Brad DeLong got it right: THE NEW YORK TIMES PUBLISHES CASEY MULLIGAN AS A JOKE, DOESN’T IT?

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2012/07/the-new-york-times-publishes-casey-mulligan-as-a-joke-doesnt-it.html

26. July 2012 at 06:32

“Yes, Mulligan is a UC economics professor. And yes, Milton Friedman is spinning faster and faster in his grave.”

http://www.smbc-comics.com/?id=2429

Sometimes I think that this is the most sensible explanation for the things coming out of Chicago and from the old monetarists.

26. July 2012 at 06:46

Scott, want to weigh in on this: http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2012/07/my-favorite-things-china.html ?

And I doubt you feel like Greg Ip does here: http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2012/07/how-euro-was-saved

26. July 2012 at 06:50

http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2003/20031002/default.htm

26. July 2012 at 07:26

Joining the linkfest, here is Ed Dolan: http://www.economonitor.com/dolanecon/2012/07/26/some-charts-that-explain-doubts-about-quantitative-easing-and-what-they-mean-for-the-fomc/

Considering that Paul Krugman of all people was yelling about how targeting expectations is key to nullifying the liquidity trap all the way back in the early 1990s, it’s ridiculous that commentary like this is so rare. We’ve known all along that expectations are key, and yet the Fed has routinely been allowed to get away with closed-ended QE policies and ignoring inflation expectations.

26. July 2012 at 07:29

Mulligan: silliness cubed.

26. July 2012 at 07:41

Mulligan doesn’t even understand what the Fed Funds Rate is. He seems to be confusing it with the Discount rate.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t the worst piece of analysis by a professional economist I read in the newspaper yesterday. This was;

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/opinion/2018772226_guest26kevincahill.html

————–quote————–

MY brother, Brian, has been a Mariners fan since 1983, when he was just 13 years old. Brian called me on Monday night with the news. “Can you believe they traded Ichiro after 11 years with the Mariners?”

….All I can offer my brother and other die-hard Mariners fans is some insight as an economist.

It’s worth asking: How did we get to this point? Our short-term-relationship mentality extends beyond sports to the employer-employee relationship in general.

At least part of the answer lies in the 30-year decline of traditional pensions, also known as defined-benefit plans, toward 401(k) plans, also known as defined-contribution plans.

————–endquote————-

Even with an annual paycheck of $18 million you can’t be expected to provide for your own retirement.

26. July 2012 at 08:34

From the abstract of the “new research” that he cites:

This is consistent with a passive Fed that follows the

market, but it is also consistent with a Fed that controls rates and a market that adjust rates to reflect

predictable Fed actions.

I know that EMH is only right-ish, but isn’t the latter possibility way more likely than the former? Everybody is getting the same unemployment reports, corporate earnings, etc., and unless the Fed acts literally insane the market should be able to figure out whether the Fed believes the economy is sluggish or overheating. I have to read this paper…

26. July 2012 at 09:22

I don’t think you are being completely fair to Mulligan. If you read the entire post, he’s clearly saying that the Fed does not necessarily have a great deal of influence over key interest rates other than the Fed Funds rate. Specifically, he refers to Fama for the proposition that the Fed does not have a lot of control over long-term rates. He was *not* talking about the stock market, much less short term swings in the stock market. Yet, the chart thrown up here seems to be a short-term effect on equity futures.

In fact, Fama and Mulligan are not alone. Respectable non-Chicago school economists such as James Hamilton, have argued that, for a variety of reasons, the Fed’s Operation Twist and QE operations have had very modest effects on long-term interest rates—the type of rates that would typically affect homeowners. Long-term rates are at an historic low, but that does not necessarily mean that the Fed is responsible for those low rates.

Here, for example, is a note by the SF Fed, citing, among others, Hamilton, in support of much of what Mulligan seems to be saying.

http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/letter/2011/el2011-13.html

26. July 2012 at 09:31

In his autobiography, Greenspan actually states that the Fed followed the market when targeting rates.

There is other research that points to a similar conclusion – Daniel Thornton’s work at the St. Louis Fed comes to mind. Thornton finds that the Fed is in the business of interest-rate smoothing, i.e. the Fed reacts to economic shocks by trying to smooth the transition from one rate equilibrium to another.

He also considers alternatives including “open mouth” operations in which the Fed only needs to state a new target to make the market move. I believe the conclusion on open mouth operations was that there is a short term market reaction to a Fed target announcement, but that it dissipates relatively quickly unless backed by actual market operations.

Thornton does caveat his claim, however, by stating that the Fed CAN significantly affect interest rates, but this wasn’t the Fed’s MO pre-crisis.

Deidre McCloskey has a less technical, but far more enjoyable, article along the same lines called “Alan Greenspan Doesn’t Influence Interest Rates.”

26. July 2012 at 09:45

Scott, do you ever read cochrane’s blog? You have a lot of fans in the comment section there.

26. July 2012 at 10:09

A recent post by David Lucca and Emanuel Moench from the NY fed suggests that 80% percent of the equity risk premium is tied directly to a “pre-fomc announcement drift.” Was Mulligan writing that post as a joke?

“For many years, economists have struggled to explain the “equity premium puzzle”””the fact that the average return on stocks is larger than what would be expected to compensate for their riskiness. In this post, which draws on our recent New York Fed staff report, we deepen the puzzle further. We show that since 1994, more than 80 percent of the equity premium on U.S. stocks has been earned over the twenty-four hours preceding scheduled Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announcements (which occur only eight times a year)””a phenomenon we call the pre-FOMC announcement “drift.”

http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2012/07/the-puzzling-pre-fomc-announcement-drift.html

26. July 2012 at 12:14

[…] me finally quote Scott Sumner who is as puzzled as I am about Mulligans comments: “Yes, Mulligan is a UC economics […]

26. July 2012 at 12:16

I love the description of the EMH: EMH is “true . . . er . . . truish.”

That’s part of the problem, isn’t it? The EMH is true in many respects (Michael Jensen’s 1964 paper showing that fund managers don’t have alpha has been repeated many times with new data).

But it’s only “truish”, not true. Because of limits to arbitrage, and herding, and noise traders etc.

But lots of people have an interest in pretending to regulators that EMH is true, not truish, because that minimises intervention.

It would be interesting to see you expand further some time on “EMH is truish”. Thanks!

26. July 2012 at 12:24

Reading this and the Arnold Kling post linked to below really ruined my day.

If conservative/libertarian economists can’t do better than this, then we are doomed.

26. July 2012 at 12:36

Mulligan: “New research confirms that the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy has little effect on a number of financial markets, let alone the wider economy.”

Let’s start with the fact that everyone who works in the financial markets thinks this is nonsense.

Exactly.

These “researchers” remind me of all the monetarist types who believe inflation has “little effect” on relative prices and relative nominal demands, and thus “little effect” on economic calculation, and thus “little effect” on sustainable productive coordination.

Free market economists all just being dishonest, or crying crocodile tears, on how “fragile” the free market economy is that it can’t even accommodate non-market determined interest rates and can’t even acquire knowledge of unobservable interest rates, as if investors can acquire empirical knowledge of market interest rates that are unobservable.

Then I laugh because not only is this argument false on its own terms, but it also undercuts the central bank apologists own argument, because if the market was so incredible that investors are even able to acquire empirical knowledge of market interest rates that are unobservable, then surely we don’t need central banking at all, and the amazing investor wizards in the private market can produce money subject to profit and loss, and the state will not use coercion to force people to accept the central bank’s money through taxation in US dollars only.

We’re only supposed to do the Keynesian thing and focus on the total of what is spent by those who do business on an arbitrary geographical territory. Individual, firm, city and state level NGDP is not magic. But country level NGDP, that is magic. That is the driver.

Even when we see charts like this, we’re supposed to ignore what it means, or pretend that monetary inflation doesn’t alter the structure of production and is not revealed when monetary inflation decelerates.

NGDP…what no investors even feel like spending but 5 minutes agreeing to a bet with anyone else. Why aren’t market monetarists making bets with each other concerning NGDP? If NGDP is so important to their interests, then certainly even the supporters of NGDP futures would be making such bets on INTRADE, or some other inexpensive market where the benefits outweigh the costs.

Has NGDP futures not failed the market test? I think it’s been enough time for the more cunning and entrepreneurial of the population to have made their judgment on the usefulness of them. Their verdict: BUPKUS.

Oops, I forgot, central planning intellectuals don’t understand the market, they want to plan society from the top down, for people’s own good, which is of course known by MMs. Market be damned.

26. July 2012 at 12:37

Josiah:

If conservative/libertarian economists can’t do better than this, then we are doomed.

Explain.

26. July 2012 at 12:49

Andrew:

But lots of people have an interest in pretending to regulators that EMH is true, not truish, because that minimises intervention.

It goes the other way too. Lots of people have an interest in pretending to voters that what I coined as “EGH” is true. EGH, or the Efficient Government Hypothesis, is the theory that governments are informationally efficient, which has the consequence that special interest groups cannot systematically achieve returns in excess of average returns, on a political risk adjusted basis, and thus cannot impose systematic costs on others, given all the information known at the time a law is designed and/or coercion is used.

There are three forms of EGH:

1. Weak: Votes already reflect all past publicly available information.

2. Semi-strong: Votes reflect all publicly available information and that voting in new politicians instantly changes to reflect new public information.

3. Strong: Votes instantly reflect all information, even insider information such as what the CIA and NSA and Fed are up to behind closed doors.

Statists have a very high incentive in pretending to skeptical individuals that EGH is true in one form or another, because it minimizes free market activity, and maximizes state intervention.

26. July 2012 at 13:03

And the stupidity will continue until the moral improves.

Etienne Yehoue, a senior economist at the IMF, argues in a new paper, that allowing the rate of inflation to rise to help bring down unemployment and spur economic growth, is probably not worth it. He estimates that letting inflation rise to 4% would cost the economy about 0.3% of real income. If inflation were to rise even higher, to 10% for example, the costs could rise to 1% of real income.

But here’s the kicker. According to Yehoue most of that damage would come from the “opportunity cost” of holding money: when inflation is higher, people spend more time and effort trying to avoid holding on to money.

In other words, in order to fix a situation partially caused by excessive money demand, we should avoid increasing the supply of money becuase it might lead to decreased money demand.

The paper is here:

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=26103.0

It’s useful to remind ourselves that the IMF’s Blanchard was advising the exact opposite of Yehoue back in February of 2010.

P.S. I’ve been reading a lot of weird nonsensical stuff over at the Financial Times lately. Is it me, or does it seem like Isabella Kaminska has everything bass ackwards on monetary policy? She seems to define “deflation” in terms of falling interest rates and thinks the antidote is to raise them. She’s especially concerned that ending IOER could hurt money market funds (poor things) and lead to a deflationary spiral which will draw the entire planet into a financial black hole in which death is certain and from which there will be no escape.

P.P.S. I also read some incredibly nonsensical stuff by self proclaimed “anti-economist” Phillip Pilkington posted at Naked Capitalism recently. (Don’t ask me why. I guess I’m just a glutton for punishment.) He quoted an MMT paper approvingly recently that makes the case (I kid you not) that increased federal deficits cause corporate profits to rise. This was done by interpreting a NIPA accounting identity as implying variable behavioral. I’m gradually coming to the opinion that MMTers all suffer from a peculiar form of autism.

26. July 2012 at 13:09

So many links, so little time. Thanks everyone.

Saturos, I agree with Ip’s hypothesis that euro stock markets are likely to outperform Wall Street over the next decade.

Nick, That seems reasonable.

Vivian, I strongly disagree. Monetary shocks affect all the financial markets quite strongly. The T-bond market crashed at the exact same time as stocks soared in the graph I provided. Policy also affects the forex markets. He’s also wrong about monetary policy not affecting the broader economy. Hamilton would view his post with disdain, as he believes monetary policy failure played a big role in causing the Great Depression. I’d consider that affecting “the economy.”

I agree that QE had only a modest effect on long term rates, no one ever denied that. But monetary stimulus does not primarily work by lowering long term rates (although it can happen) it works by raising expected NGDP growth. And of course higher expected NGDP growth raises long term rates. In any case no UC economist should EVER describe the stance of monetary policy in terms of long term nominal rates. QE raised inflation expectations sharply, and it seems likely that NGDP expectations rose as well.

Justin, I agree they often followed the market.

ChargerCarl, I do on occasion, but lack of time limits how many blog posts I can read. I like his non-monetary stuff best–health care, etc.

Ryan, Yes I saw that, although I doubt whether it will hold up in the future.

Andrew, I’ve done many EMH posts. My first and most complete was something like Richard Rorty and the EMH. Perhaps my search box could find it.

Josiah, That wasn’t Arnold’s best. But I’ll say this, he’s way ahead of me on regulation, and many other issues.

26. July 2012 at 13:11

Mark, I agree, and have seen some of those as well. It’s the silly season.

26. July 2012 at 13:27

The European markets didn’t respond at all today to Draghi’s London comments live on he web at precisely 11.08am BST. Not much!

26. July 2012 at 13:38

Monetary shocks affect all the financial markets quite strongly.

If a producer invests in fake dog poop, and he and his employees experience a “monetary shock” when the fake dog poop fad subsides, then what is the justification for printing money to ensure that neither he nor his employees experience a decline in nominal incomes? If there is no justification here, then there is no justification for bailing out two such parties, or three, or four, or five, or six, or seven, or eight (please stop me when you want to use the magic word “recession” and reverse your logic and say printing money to prevent losses is now justified!), or nine, or 10, or 11, or 12, or 13, or 14 (again, please stop me when you want to use the magic word “recession” and when you want to reverse your logic!), 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 (have any of you said the magic word yet?), 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 (anyone? No?), 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 (what’s the problem?), 33, 34, 36, 38, 39, 40 (you can’t even find a justified reason to say the magic word “recession” in this way can you?), 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 (look at all these bankruptcies so far, and you callous market monetarists refuse to say the magic word!), 46, 47, 48, 49, 50…

It is arbitrary, groundless, and devoid of rational justification to EVER support fiat inflation so as to prevent rising unemployment and declining profits. This is why we have to use the magic word “recession” for countries, or more specifically, to geographical territories over which monopoly money printers have violence backed privilege to extract real wealth from people from purchasing power tax. Then we can pretend to be all concerned about employment and output and all the rest. For if NGDP collapses for an individual, who gives a shit. If NGDP collapses for a firm, who gives a shit. If NGDP collapses for a city, who gives a shit. If NGDP collapse for a state, who gives a shit. But, when NGDP collapses for a country, OH MY GOD SAVE THE CHILDREN BECAUSE NOW THE EXPLOITERS CANNOT EXTRACT AS MUCH REAL WEALTH AS BEFORE.

You guys are servants and sheep for those who have exploitative power over you and I. This is ultimately why I seem to appear as callous/obnoxious/spiteful/etc. It’s because I have next to zero intellectual respect for people who are too dimwitted so unplug themselves. You have the same responses as those who were slaves in the Gulags. They too called the ethical egoists demagogues, conspiracy theorists, whiners, not respecting of authority, wanting to collapse civilization, haters of the poor, etc, etc. It’s your intellectual conditioning that I despise.

26. July 2012 at 13:48

Scott,

The NY Fed’s “Liberty Street” economics blog examined more systemically the effects of Fed actions on financial markets. What they found is that more than 80 percent of the equity premium is derived from the 24 hours preceding FOMC announcements. The S&P would be at 600, not 1300, if the gains made before FOMC announcements were removed.

http://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2012/07/the-puzzling-pre-fomc-announcement-drift.html

The evidence for monetary policy’s influence in financial markets is staggering.

26. July 2012 at 14:00

Scott,

Mulligan is largely channeling Eugene Fama based on the latter’s very recent paper. You should read the following paper and then critique that. Here’s the abstract:

“Strong statements about the effects of Federal Reserve actions on interest rates are common in the media and among academics. I’ve long been puzzled by such claims since the Fed seems to be a minor player in financial markets. In recent years total U.S. credit market debt, as reported in Federal Reserve Flow of funds tables, is in excess of $50 trillion. Prior to the financial crisis of 2008, total financial assets held by the Fed are less than $1 trillion, or less than two percent of the U.S. market. In response to the financial crisis of 2008, total financial assets held by the Fed jump to over $2 trillion and are almost $2.5 trillion at the end of 2010. This is huge by historical standards, but still less than five percent of the U.S. market. Many large banks (e.g., J.P., Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Citibank, Wells Fargo, etc.) have balance sheets comparable in size to the Fed’s. Moreover, the U.S. credit market sits in a large international market that is open to major market participants (governments and large private firms, financial and nonfinancial) around the world, and the big players can and do operate across markets. In this context, it may seem implausible that the Fed has more than a minor role in determining interest rates, except to the extent that it can affect inflation expectations. It seems even more implausible that in an open international bond market, multiple central banks can separately control interest rates in their local markets.”

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2089468

26. July 2012 at 14:01

The evidence for monetary policy’s influence in financial markets is staggering.

The evidence that the Fed creates stock market bubbles, despite NGDP being “stable”, is equivalently staggering.

26. July 2012 at 14:25

Scott, this is a low point for the University of Chicago. I wonder what Mulligan think of today’s rally in S&P500. Why did that happen? Was it a positive technology shock or did it have anything to do with what ECB chief Draghi Said:

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-07-26/european-stocks-spanish-bonds-rise-on-draghi-as-dollar-slides.html

Here is my post on Mulligan’s nonsense:

http://marketmonetarist.com/2012/07/26/did-casey-mulligan-ever-spend-any-time-in-the-real-world/

26. July 2012 at 15:27

And, while you are at it, you might want to critique this latest from Krugman:

“Mulligan tries to refute people like, well, me, who say that the zero lower bound makes the case for fiscal policy. My argument is that when you’re up against the ZLB (OK, it’s more a minus 0.1 percent bound, but no significant difference), conventional monetary policy is ineffective, so you need other tools.”

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/

26. July 2012 at 15:31

Hey Major_Freedom:

Mike Norman and MMTers are off the leash and I’m tied up with real work tonight. There’s PLENTY of grist for the mill.

http://mikenormaneconomics.blogspot.com/2012/07/which-part-of-dynamic-systems-dont.html

If you have the interest or energy.

26. July 2012 at 15:36

So Vivian you agree with Mulligan? I thought everyone thought Mulligan is the one writing nonsense not Krugman

26. July 2012 at 15:42

“So Vivian you agree with Mulligan? I thought everyone thought Mulligan is the one writing nonsense not Krugman”

1. Did I say I agree with Mulligan? I said that I thought the criticism was not completely fair. In other words, that his post was being somewhat misconstrued. I did *not* say that I agree with him.

2. Who the heck cares what “everyone” thinks?

26. July 2012 at 15:57

James, Good point.

Vivian, Fama isn’t a macroeconomist, and as far as I can tell doesn’t even believe in the income and liquidity effects, just the inflation expectations effect. He’s just about the only person in the world who believes there’s no liquidity or income effect, except apparently Mulligan. (And BTW I like Fama as an economist.)

The effect of Fed policy on interest rates has very little to do with the size of the bond market or the percentage of bonds bought by the Fed. It works through macroeconomic channels, not finance channels. In other words it’s not because they are buying bonds. If the Fed bought gold there’s still be a big effect on i-rates.

Lars, Yes, very disappointing.

26. July 2012 at 16:05

Vivian speaking of “everyone” do you use this charm for everyone or do you save it for me.

I know that no one takes more unfair potshots than Krugman does.

26. July 2012 at 16:14

EMH is true!

What does the EMH say? That the market quickly incorporates all (publicly available) information.

Correlary, it is impossible to regularly beat the market (based on public information.)

Implication, the next move of the market is difficult to predict.

So, for those who look at the collapse of 2008 and say that this is proof that the market is inefficeint. I say, did you see that comming? And, while some have claimed that they did, none placed a bet on it.

It does not say that equity returns are lognormally distributed, or that market movements are continuous. In fact, is suggests the opposite, that large discontinuous moves will happen.

26. July 2012 at 16:19

Doug:

“So, for those who look at the collapse of 2008 and say that this is proof that the market is inefficeint. I say, did you see that comming? And, while some have claimed that they did, none placed a bet on it.”

Yes I did see it coming and I did place a bet on it. I bought lots of puts on the banks and saw returns of 400%

Paulson obviously made huge bets.

26. July 2012 at 16:24

Scott,

I am not agreeing or disagreeing with Fama. But, frankly, whether he’s a macro economist or not is, for me at least, irrelevant to the issue of whether he’s right or wrong on this particular point. It has nothing to do with the substance of his argument.

I understand Fama has concentrated most of his research on markets. And, as far as I know, markets do have something to say about what interest rates are at any given point in time. Of course, this does not mean that he would know more than a macro economist; but, on the other hand, it should not be an argument against him.

26. July 2012 at 16:43

The Fed has no impact on financial markets or the trader economy?

Yahoo! Let’s have the Fed buy up the entire national debt.

The interest payments from the debt, funneled back in the Treasury, would allow huge tax cuts.

26. July 2012 at 18:01

“So, for those who look at the collapse of 2008 and say that this is proof that the market is inefficeint. I say, did you see that comming? And, while some have claimed that they did, none placed a bet on it.”

Before I answer that, let me first say something about financial assets and then separate all price movements into two different categories.

First, perhaps the biggest issue with the typical EMH mindset (not necessarily the EMH itself) is thinking of asset prices as mere particles bouncing around based purely on the “z” factor in the brownian motion equation. In fact, financial assets are a real claim on future cash flows and, whatever the market’s price is, the intrinsic value is the actuarial valuation of the expected discounted cash flows. The market value does not necessarily equal intrinsic value just because the EMH says it should.

With the actuarial value of financial assets in mind, let’s separate asset price movements into two categories.

1. The price changes due to new information and the market changes the assumptions on their actuarial valuation.

2. Price changes due to something other than news changing the expected actuarial valuation. This category comprises whatever irrational action causes prices to become detached from their intrinsic value and then whatever catalyst causes prices to correct to the intrinsic value.

In arguing that there are no asset bubbles or whatever, very odd circular arguments can arise. The argument for no bubbles seems to be that the EMH says big price decreases will eventually happen. 0.3% of the time, you’re going to get those two-sigma events and therefore the EMH does say big price decreases would happen. However, that argument does not exclude whether prices after a bubble were simply adjusting to their intrinsic value. It just says that it’s possible a big price drop was due to new information.

To tease out whether the price drops in stocks in 2001 or in mortgage-backed securities after 2007 were corrections or simply new information, we can examine the actuarial assumptions that would justify the prices at the bubble’s peak. In both cases, even the most wildly optimistic assumptions about cash flows did not support their prices.

In the case of mortgage-backed securities, many of the subprime mortgages would have defaulted even if housing prices did not decrease. This is because interest accruing to principal increased LTV at a far greater pace than historical rises in housing value. Even if housing prices merely leveled off in 2006, many of the subprime mortgages would have defaulted. Therefore, this isn’t a case of housing prices happening to be on the wrong side of the z term. It was investors putting money in and only getting money back out if housing prices continued to rise at a historically very high pace.

So, now, with all this wisdom, why didn’t I make money shorting the market? The question reminds me of a supposed encounter between an old economist and an investor. The investor asked, “if you are so smart, why aren’t you rich?” The economist replied back “if you are so rich, why aren’t you smart?”

In this case, I didn’t short it because I was not involved or interested in the opaque market of mortgage-backed securities. I would have expected though that the investors intimately involved in that market would have prices close to their intrinsic values. As I show above, many investors put in money while only getting it out if house prices continued to rise at a two-sigma plus rate.

There is also the issue that a mispricing does not mean that it’s personally profitable for investment managers to short the market. Investment managers need to ultimately retain capital and not have capital decrease while waiting on the short to come true. Real people with real money ultimately have to fund all the margin calls (or protection payments in the case of CDS) while waiting possibly years on a short to come to fruition.

There is a further problem that bubbles typically happen only in assets which are unfamiliar to most people with money. For this reason, the Tech bubble didn’t push stocks like Proctor & Gamble to unprecedented heights. It pushed up stocks that traders did not have familiarity with how to value. Presented with unfamiliarity, the human mind can easily take shortcuts.

I’m sure that sounds pretty out there, but it is for this reason that there may not be enough investors to short and correct a mispriced market. Some investors might be smart enough to short a market, but bubbles happen as the smart investors cannot outweigh those who believe a certain story of an asset, even if careful analysis shows that prices are not justified by future cash flows.

All that said, I am not a big fan of the pure Keynesian “beauty contest” explanation either. Those skeptical of the EMH have been given a bad name by those who seem to say the market is usually wrong. Especially in very liquid, very experienced markets like Treasuries or the vast majority of the S&P 500, market and intrinsic valuations track closely.

26. July 2012 at 18:01

Scott, I meant Berezin’s suggestion that the best we can hope for is the Euro being saved.

26. July 2012 at 18:30

[…] graph above ties in with Sumner’s new post regarding the ‘irrelevance’ of monetary policy in driving financial markets. Care to […]

26. July 2012 at 19:46

JW Mason has an interesting piece on this, disputing the relationship between central-bank-set short rates and long rates. I’m not taking sides for now, but worth a read:

http://slackwire.blogspot.com/2012/07/does-fed-control-interest-rates.html

26. July 2012 at 20:51

“He’s just about the only person in the world who believes there’s no liquidity or income effect…”

Not to beat a dead horse, but Daniel Thornton (“Monetary Policy: Why Money Matters and Interest Rates Don’t”) certainly believes, and he cites work by James Hamilton that shows the liquidity effect is quite hard to detect.

“The effect of Fed policy on interest rates has very little to do with the size of the bond market or the percentage of bonds bought by the Fed. It works through macroeconomic channels, not finance channels. In other words it’s not because they are buying bonds. If the Fed bought gold there’s still be a big effect on i-rates.”

I’m not quite sure I buy this. Are you saying buying $100B of t-bills would have the same impact on rates as buying $100B of gold? If not, how is the difference not a result of the “financial channel”? Moreover, isn’t the liquidity effect a financial phenomenon? Of course, this may be an issue of semantics…

26. July 2012 at 20:59

Doug M.,

What a wonderful description. It took me from “I understand the Efficient Markets Hypothesis” to “I could explain it to others!” Thanks.

-Allen

26. July 2012 at 21:58

JW Mason made the best argument I have seen on the contrary: http://slackwire.blogspot.com/2012/07/does-fed-control-interest-rates.html

26. July 2012 at 23:07

Scott Sumner, speaking about people rolling in their graves…

I think you might have a few words for Philip Pilkington over at Naked Capitalism and at Steve Keen’s blog.

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2012/07/25/philip-pilkington-market-monetarism-or-an-attempt-to-speed-up-the-decline-in-real-wages/

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/07/philip-pilkington-market-monetarism-or-an-attempt-to-speed-up-the-decline-in-real-wages.html

27. July 2012 at 00:56

Scott, I am not sure what you mean by “macroeconomic channels”. I agree that if the Fed buys gold, it should lower interest rates, because the Fed pays with base money, meaning that they increase the stock of a substitute for short-term debt. Is that not a “financial channel”?

Like Justin R., I do believe that the effect should be bigger if the Fed buys t-bills, though, because they ARE short-term debt. This old post of mine explains my thinking, in the context of foreign exchange intervention: http://reservedplace.blogspot.co.uk/2008/07/to-peg-is-not-to-hold.html

Whether this effect on short-term interest rates is SIGNFICANT however, is something that has puzzled me for years. As others have written (the article that influenced me most was this, by another Friedman: http://www.nber.org/papers/w7420.pdf ), in normal times, the central bank balance sheet is too small in relation to the banking system balance sheet to have a significant effect on interest rates. This is not the case now though, so I think that it is necessary to distinguish between the pre and post QE situations.

27. July 2012 at 02:28

ah, I was going to add another link (but supply no more time)

to JW Mason at Slackwire, but I see Steve W has beaten me to it. His arguments need taking seriously imho.

27. July 2012 at 05:26

It’s a little over my head, but if I’m reading Fama right, he says that empirically, for the period 9/1982 – 6/2012, when the Fed has changed its target rate, short term interest rates have moved but long term haven’t.

Assuming Fama’s right, this is consistent with (1) on average, the market players don’t believe that the short term fed moves reflect a change in long term strategy or (2) on average, the market players believe that the fed’s move will affect underlying real activity in a way that keeps long term demand for money the same. Is that right? ((2), obviously, is the part that’s over my head, at least until I get out a pencil and paper to noodle out the model).

27. July 2012 at 06:06

I have actually read through the paper now and I stand by my earlier comment. People who claim to be unable to see the relationship between FF and other rates merely by looking at a plot of the series (such as the slackwire link) are right – but when you actually run autocorrelations on the convergence, as in the paper, there is definitely convergence for short term rates. That’s why we do math instead of look at pretty pictures to answer hard questions (I know – but “math is hard!”).

Fama does find a relationship between short term rates and the Fed target, so there is no doubt that they move together (converge). But what he tries to show is that since the CP rate does not move *after* the Fed funds target is changed (based on the impulse response function of his VECM model), that the CP rate move is not *caused* by the change in Fed funds target. His argument implies that causality can only be established when the thing that is caused happens after the thing that does the causing occurs first. And while that seems straightforward, the most basic part of rational expectations and EMH is that expectations of something can have actual effects before that something actually occurs.

So although it is strange to say that A (Fed target rate change) causes B (convergence of CP rate to the new Fed target) before A actually happens, that is precisely what is happening here. It is entirely consistent with markets that have fully incorporated an expected Fed change in the target rate *before* the change is made purely because of expectations of the Fed change. The conclusion that the Fed does not cause changes in short term rates is therefore too strong and is only one possible interpretation of his results (and for anyone who believes that markets do not purposefully ignore pertinent upcoming events it is the less likely alternative).

As for long term rates, any change in long terms rates as a result of (and in the same direction as) the change in the short term rates is met with a change in long-term inflation expectations that pushes long term rates in the opposite direction, so it is no surprise that the relationship between the Fed target and long term rates is weak (or, to put another way, the relationship is too complex to be modeled with this kind of analysis).

27. July 2012 at 07:50

Doug –

“So, for those who look at the collapse of 2008 and say that this is proof that the market is inefficeint. I say, did you see that comming? And, while some have claimed that they did, none placed a bet on it.”

Good question, but there’s a difference between predicting something is likely to happen and predicting the timing. I predicted that housing would fall several times and it kept going up. I was finally “right”, but if I had made bets I probably would have lost money because I would have gotten the timing wrong. I suspected it was a bubble, but how did I know if it would go up another 50% and then pop? “The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.”

Same thing with the gold bubble. It peaked at over $1900 an ounce, and now it’s in the 1500’s. I knew it was a bubble, but how would I know if it would pop at $1900 or $3000?

Of course, this has nothing to do with whether the market is “rational” or not, which seems more like a philisophical question to me. To some, the price is always “correct” based on current information, so it’s always rational. Sounds like a tautology to me. To others, if there’s a change, that means the price was incorrect. In which case the market price is always incorrect. “Jerry, I told you the market fluctuates!” I don’t really take sides in that question.

27. July 2012 at 08:31

Fama;

‘In this context, it may seem implausible that the Fed has more than a minor role in determining interest rates, except to the extent that it can affect inflation expectations.’

Milton Friedman could have told him that…and probably did.

27. July 2012 at 08:36

‘What does the EMH say?’

Coincidentally, I’m reading a book with the off-putting title, ‘The Myth of the Rational Market’ by Justin Fox. It’s a history of the development of the EMH and is exceptionally well written. Maybe the best book on economics by a journalist I’ve ever read.

But, he should have title it, ‘The Myth of the Myth of the Rational Market’.

27. July 2012 at 09:05

Mike Sax:

Yes I did see it coming and I did place a bet on it. I bought lots of puts on the banks and saw returns of 400%

Mike the bigot is living in a fantasy land.

27. July 2012 at 09:17

Roche has a good take here. http://pragcap.com/who-cares-about-the-fed-funds-we-all-do

27. July 2012 at 09:27

People who claim to be unable to see the relationship between FF and other rates merely by looking at a plot of the series (such as the slackwire link) are right – but when you actually run autocorrelations on the convergence, as in the paper, there is definitely convergence for short term rates. That’s why we do math instead of look at pretty pictures to answer hard questions

Well, I am going to defend the look-at-pretty-pictures methodology.

Remember, the question we are interested in is not if there is *some* positive relationship between the policy rate and the economically important long rates. There is no question that there is. The question is whether there is an *economically important* relationship. The question is whether monetary policy, as conventionally conducted, can move economic aggregates far enough and fast enough to stabilize the economy in the face of business-cycle scale shocks. In other words, should we believe that if it were not for the zero lower bound, monetary policy as conducted during the past few decades could reliably have prevented this recession from being deeper than the recessions of the early 2000s or early 1990s, making fiscal stabilization irrelevant. I think both Mulligan and Krugman/DeLong would agree that’s the issue.

Given that, *if* you believe that the main channel of monetary policy is long-term interest rates (and I take Scott S.’s point that it may not be), then for stabilization via monetary policy to be feasible, policy needs to have a *large* effect on long-term interest rates. If policy effects are so small that it takes careful econometrics to pick them out from noise, then they are too small to be useful for stabilization.

(Econometric technique is mainly necessary to avoid Type I error — it is easy to look at a graph and see a relationship that is not there.)

27. July 2012 at 09:36

Hmmmm…I think the post didn’t get through. Sorry for the double posting if the original one did get through.

ssumner:

Andrew, I’ve done many EMH posts. My first and most complete was something like Richard Rorty and the EMH. Perhaps my search box could find it.

Let’s see what you had to say about Rorty:

“Thus Rorty suggested that it was pointless to argue about whether something is an objective fact or a justified belief, as we have no access to an extra-human perspective, and thus can never resolve the debate.”

We don’t need to have “extra-human perspective” to know objective facts. There are facts of reality that are human perspective based. Not mere whims or opinions, but painstakingly thought out a priori propositions that say something true about empirical reality.

More importantly however, why can’t you realize that Rorty is proposing a clearly self-contradictory system? If Rorty denies objective knowledge is possible, then he cannot claim his own propositions are objectively true as he clearly is presenting them as being, and which you too are presenting them as being. You’re saying no objectively true knowledge is possible, and yet that is supposed to be taken as an objectively true statement concerning the efficacy of human knowledge.

——————

Let’s dig into what Rorty believes. I cite from his magnum opus, “Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature”.

“I have argued (in chapter three) that the desire for a theory of knowledge [MF: i.e. Rationalism] is a desire for constraint-a desire to find “foundations” to which one might cling, frameworks beyond which one must not stray, objects which impose themselves, representations which cannot be gainsaid.” – pg 315.

“The dominating notion of epistemology is that to be rational, to be fully human, to do what we ought, we need to be able to find agreement with other human beings. To construct an epistemology is to find the maximum amount of common ground with others. The assumption that an epistemology can be constructed is the assumption that such common ground exists. – pg 316.

Rorty believes that no such common ground exists, therefore the false idol of rationalism must fall and a “relativist” position called hermeneutics must be adopted:

“Hermeneutics sees the relations between various discourses as those of strands in a possible conversation, a conversation which presupposes no disciplinary matrix which unites the speakers, but where the hope of agreement is never lost so long as the conversation lasts. This hope is not a hope for the discovery of antecedently existing common ground, but simply hope for agreement, or, at least, exciting and fruitful disagreement. Epistemology sees the hope of agreement as a token of the existence of common ground which, perhaps unbeknown to the speakers, unites them in a common rationality.”

“For hermeneutics, to be rational is to be willing to refrain from epistemology-from thinking that there is a special set of terms in which all contributions to the conversation should be put-and to be willing to pick up the jargon of the interlocutor rather than translating it into one’s own. For epistemology, to be rational is to find the proper set of terms into which all the contributions should be translated if agreement is to become possible. For epistemology, conversation is implicit inquiry. For hermeneutics, inquiry is routine conversation. Epistemology views the participants as united in what Oakeshott calls an universitas-a group united by mutual interests in achieving a common end. Henneneutics views them as united in what he calls a societas-persons whose paths through life have fallen together, united by civility rather than by a common goal, much less by a common ground.” – pg 318

If one spent some time digesting all of this, and then engage in self-referential logical analysis, we can find the fundamental flaw in Rorty’s philosophy. This flaw can be revealed by asking the fair and reasonable question: “What are we to make of Rorty’s own pronouncements?”

Since Rorty (and virtually every other adherent to the ancient umbrella creed of relativism) didn’t bother checking his work for self-referential consistency, his readers have to do it. Well, I’m a reader, and I say OK, if there is no such thing as knowable truth based on common, objective ground, then Rorty himself cannot claim to have said anything true, lest he contradict his entire thesis.

But if we are supposed to take his words not as something true, but rather as another “strand” in a possible conversation, then Rorty is not actually claiming what he seemed to have claimed, which is that his philosophy is objectively superior to rationalism, that he knows the truth of this, and that he wants his readers to accept the truth of this. Rather, he is just entertaining us, the way a musical artist or poet entertains us. In fact, if Rorty’s logic is again universally applied, then I could not even claim that it is true that I myself am being entertained or not entertained, nor that this is what Rorty actually intended for his readers.

So what is Rorty in fact saying? If he’s right, then I could not even claim to know what he is saying, because that would belie Rorty’s (self-contradictory) won thesis that objective knowledge is impossible. I could not claim to know that he said what he seemingly intended to say.

Rorty’s thesis is not only self-contradictory, but it also inadvertently presupposes the truth of “objective, common ground” epistemology, i.e. rationalism. For in order for Rorty to claim to have said anything meaningful at all, unless we all agreed to common ground meanings for “engaging in hermeneutics”, “being persuased”, “having a conversation”, and so on. We could not even deny this without presupposing the same common ground meanings for concepts. Of course, this common ground is not one of a freely floating conventional system of symbols and sounds hanging in mid-air, which could in principle be something else. No, they are concepts the common ground of which enables their use and cooperation in practical affairs, in interactions. One could also not deny this without presupposing that one could establish such common ground for the practical application of what it means to make an argument, what it means to intend to show an argument false, what it means to correct a previously advanced argument, and so on.

——————-

I am therefore of the “persuasion” that Rorty can only have done what he did, and could only have said what he said, if what he said was false.

27. July 2012 at 09:41

Bad grammar. Should read:

“For Rorty could not claim to have said anything meaningful at all, unless we all agreed to common ground meanings for “engaging in hermeneutics”, “being persuased”, “having a conversation”, and so on.”

27. July 2012 at 10:41

Nick Rowe is so smart, it makes me want to cry:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/07/why-are-almost-all-economists-unaware-of-milton-friedmans-thermostat.html

27. July 2012 at 11:16

If the fed can’t, Mario Draghi sure can. By the way Scott I had been thinking about your idea of having GDP futures and I came to the conculsion that the stock market already is a proxy for that. So when people critize the fed for proping up the stock market you may want take that to heart.

27. July 2012 at 11:31

Chris Corn:

I came to the conculsion that the stock market already is a proxy for that. So when people critize the fed for proping up the stock market you may want take that to heart.

They can be ideologically “conditioned” to accept it, first by the Fed denying it, then by tacitly accepting it, then by saying it’s a necessary evil, then by saying it’s beneficial, then attack those who say otherwise.

Lather, rinse, repeat.

28. July 2012 at 09:25

Vivian, Are you defending Fama’s claim that monetary policy only affects interest rates via the inflation effect? There are mountains of data suggesting that is wrong.

Saturos. You said;

“I meant Berezin’s suggestion that the best we can hope for is the Euro being saved.”

A friendly tip—99% of the time when commenters are this terse I’ll have forgotten the original discussion.

Steve Waldman, I agree that Fed policy often moves short and long rates in opposite directions. I can’t imagine what DeLong was thinking. Of course Mulligan is still 100% wrong for all sorts of reasons.

Justin, I’m not saying the effects are identical, I’m saying that during normal times the macro channel is 100 times more powerful than the finance channel.

If there was no liquidity effect then the only way the Fed could raise interest rates is via an easy money policy. Do you believe that? Do you think if they unexpected pumped some money into the economy it would immediately raise the fed funds rate? I think what Hamilton is saying is that the liquidity effect is hard to spot using macro data at quarterly or annual frequencies. I agree.

Matt, I agree, see my response to Steve Waldman.

Blue, I’m not sure nonsense like that is even worth responding to. I gave up on MMTers long ago.

Rebeleconomist, By “finance channel” I meant policy that affects rates directly, via a purchase of some bond which raises its price and lowers its yield.

JMann, He may be right, but that has no bearing on whether monetary policy affects financial markets or the broader economy.

Nick, Excellent comment.

Saturos, Yup, Nick Rowe is the best.

Chris, The problem is that stock prices are not reliable. Remember 1987?

28. July 2012 at 10:46

“Vivian, Are you defending Fama’s claim that monetary policy only affects interest rates via the inflation effect? There are mountains of data suggesting that is wrong.”

Scott,

There is no need to defend that, because it is not what Fama has written in his paper. He indicates that the evidence he presents suggests the Fed primarily affects interest rates via inflation expectations (not that it *only* affects (longer-term) interest rates via inflation expectations), rather than through the FF rate. He says the latter likely has a minor effect, not that it has no effect.

One thing that I’ve noticed about economic arguments (other than deliberate misrepresentation of each other’sf positions) is that two people can both be correct, depending on the time frame selected. One can throw up a chart showing a four hour effect of Fed actions on stock market futures and claim that it has an effect on long-term interest rates. Another put analyze data over two decades and conclude that the Federal Reserve has a minor effect on long-term rates (over a longer time from than a few hours). The time frame to an economist is kind of like the baseline for fiscal policy makers.

I am not here to defend Fama on this particular point largely because my mind is open on the subject. I’m willing to listen to people who come to the table with reasoned positions based on scholarship and not on one-line throw-away dismissals.

What I see so far is that Fama has made a good faith scholarly attempt to address a difficult issue. What he has written makes sense to me. But, I’ve got an open mind. So, Scott, I am looking forward to the day when yo will write a scholarly paper summarizing mountains of evidence you have accumulated through painful and detailed research that addresses Fama’s rationale and his conclusions and rebuts them one-by-one. Until then, count me skeptical.

28. July 2012 at 12:03

Scott,

I agree with most of what you are saying and I’m not necessarily disagreeing with the rest – I can’t claim to have the expertise to do so! To a certain extent I think differences in opinion on the liquidity effect are based on magnitudes and time horizons, not on whether the effect exists.

Where I’m confused is the macro vs financial channel and your statement that “The effect of Fed policy on interest rates has very little to do with the size of the bond market or the percentage of bonds bought by the Fed.”

However, isn’t the size of the Fed’s injections relative to asset market sizes important? If the Fed injects $10 billion (regardless of the asset purchased), the impact on i-rates depends on whether the U.S. Treasury market is $100 billion vs $10 trillion, ceteris paribus, no?

As a side note, I believe Hamilton ultimately had to go with daily data. Again, I think it is due to the fact that the Fed’s actions pre-2008 were typically small and that the Fed was following the market.

29. July 2012 at 18:28

Vivian, As I’m sure you must know I don’t have time to compile mountains of evidence into each response to a comment. I’ve seen Fama interviewed on monetary policy and I think I have a pretty good idea of his views, which are wildly out of line with the rest of the profession. That doesn’t mean he’s wrong, but his views are inconsistent with the mountains of empirical evidence that I’ve come across in 30 years of studying this issue.

I’ve you aren’t convinced that’s fine, I’m just giving you my views.

Justin, You said;

“However, isn’t the size of the Fed’s injections relative to asset market sizes important? If the Fed injects $10 billion (regardless of the asset purchased), the impact on i-rates depends on whether the U.S. Treasury market is $100 billion vs $10 trillion, ceteris paribus, no?”

It might make some difference, but I think the primary channels are unaffected by the size of outstanding Treasury debt.

29. July 2012 at 18:52

Scott Sumner: What is your opinion of Post Keynesians like Steve Keen, out of curiosity? I think that as eminence grise of market monetarism, you ought to engage in a brutal smackdown, and call the troops! It would be like Krugman versus Keen all over again, albeit more glorious!

30. July 2012 at 17:06

Blue, I’m not really interested in addressing Post Keynesians any more. Life is too short.

30. July 2012 at 20:02

I see. If it really would work you up that much, then it’s best to choose not to slay this dragon. It’s wise to know what fights to pick and what not to pick.

21. October 2012 at 03:56

“And that’s ignoring the fact that many monetary shocks don’t even show up in the fed funds market, an issue Mulligan overlooks in the rest of his column.”

Wonderful! Couldn’t have said that better.