Does debt slow growth?

Maybe, but I’m not too clear on exactly how. Here’s the Financial Times:

Others believe the People’s Bank of China will retain its ability to ward off crisis. By flooding the banking system with cash, the PBoC can ensure that banks remain liquid, even if non-performing loans rise sharply. The greater risk from excess debt, they argue, is the Japan scenario: a “lost decade” of slow growth and deflation.

Michael Pettis, professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, says rising debt inflicts “financial distress costs” on borrowers, which lead to reduced growth long before actual default.

“It is wrong to assume that ‘too much debt’ is bad only if it causes a crisis, and this is a typical assumption made by almost every economist,” Prof Pettis wrote in a draft of an forthcoming paper shared with the Financial Times.

“The most obvious example is Japan after 1990. It had too much debt, all of which was domestic, and as a consequence its growth collapsed.”

Distress costs include increased labour churn as employees migrate to financially stronger companies; higher financing costs to compensate for increased default risk; demands for immediate payment from jittery suppliers; and loss of customers who worry a company may not survive to provide aftersales service.

Many are now concerned that China’s debt could lead to a so-called balance-sheet recession — a term coined by Richard Koo of Nomura to describe Japan’s stagnation in the 1990s and 2000s. When corporate debt reaches very high levels, he observed, conventional monetary policy loses its effectiveness because companies focus on paying down debt and refuse to borrow even at rock-bottom interest rates.

The final paragraph discusses the ineffectiveness of monetary policy. Obviously I don’t agree with that; monetary policy is always and everywhere highly effective. So if the mechanism is supposed to be “less AD”, then I’d say debt is nothing to worry about.

The preceding paragraph discusses some possible supply-side mechanisms, but they don’t seem powerful enough to have large macroeconomic effects. I suspect that Japan’s slow growth has been a mixture of tight money (low NGDP growth), low population growth, and low productivity growth. Only the productivity growth could be plausibly linked to debt, and even there the connection is tenuous.

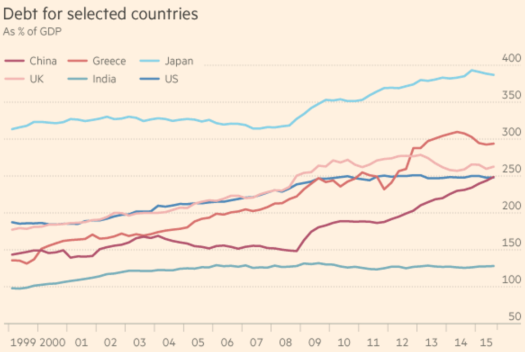

The article also has a graph putting China’s debt in perspective, total debt as a share of GDP:

Notice that China’s debt ratio is almost identical to the US. But the FT also mentions two reasons to worry:

Notice that China’s debt ratio is almost identical to the US. But the FT also mentions two reasons to worry:

1. Their debt ratio is quite high for a developing country.

2. Their debt ratio is increasing rapidly.

I’m not too worried about the first point, as China is a very unusual developing country. But the second point does seem like a cause for concern. Will the economy be able to shift away from high levels of debt formation, without triggering a recession? I honestly have no idea. My best guess is that China will have a financial crisis and recession at some point in the next 20 years, but I have no idea when.

As always, NGDPLT would make the debt crisis (if it does occur) much less severe.

PS. Note that China bears have been concerned about debt for many years now, and so far their predictions have not proved accurate.

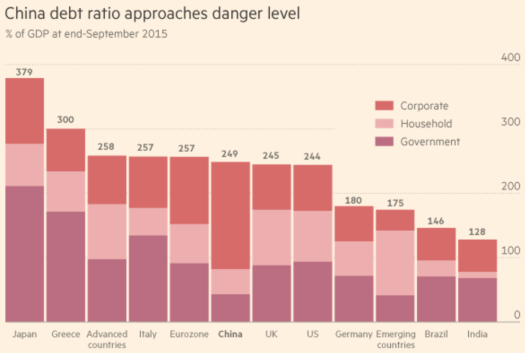

PPS. Here’s the debt breakdown by sector:

PPPS. Over at Econlog I have a new post, explaining what would make me doubt the truth of market monetarism.

Tags:

24. April 2016 at 06:12

Who to believe, Koo, or koo-koo?

24. April 2016 at 07:15

ssumner asks:

The best thinking I’ve seen on the topic suggests the answer is no.

[The article is broken across several pages, but is well worth the additional clicking to go through because it lays out a model that explains why China’s previously lower private sector debt-to-GDP ratio would not have the same impact that its now much higher private debt-to-GDP ratio would, which helps explain why the China bears in previous years were wrong and also why China’s economic state has grown to find itself in a much more vulnerable position today.]

24. April 2016 at 08:03

Credit does not slow growth.

Credit expansion slows growth. First by artificially stimulating an unsustainable boom, and then leaving waste and wreckage behind which could have been used for sustainable projects.

Since NGDPLT depends on the federal reserve banking system, NGDPLT depends on and indeed encourages credit expansion. Therefore NGDPLT will reduce growth.

24. April 2016 at 08:27

Flooding with cash, I assume means that the central bank buys the bad loans. The US Fed should have done that in early 2007. The law was not yet passed but it had been introduced to the House on 3/9/2007. Some markets would have crashed anyway, like Las Vegas, but not all markets would have crashed like they did. Kevin Erdmann thinks they wanted a big crash and more and more I am coming to believe that. That bill was ready to go, HR 1424, yet it sat while house prices cratered nationwide.

24. April 2016 at 09:03

From your second chart it appears that, while its governmental and household debt levels are quite low, China’s corporate debt level is enormous; and I assume that the very rapid increase in debt in China shown by your first chart, mainly from late 2008 to late 2009 and again from late 2011 to the present, has been mostly in corporate debt. What happened? Why have Chinese corporations just recently been taking on so much more debt, as opposed to using equity financing? If we knew why they were doing it we could better assess how hard it would be for them to stop. (But perhaps there’s not much incentive for them to stop; it is far from clear [to me] why debt is supposed to be bad.)

24. April 2016 at 09:20

In the US context, one of the themes I have been working on is the difference between an economy with liberalized capital markets and one without them. In US housing markets, most cities are the former and CA and New England are the latter. In California, more debt just represents the capitalized claim of former real estate owners on future production, resulting from real estate constraints, so it is a drag on growth. In other areas it funds new capital formation – new housing stock – and so there it is more associated with growth.

24. April 2016 at 09:38

What is “growth”? There seems to be an assumption that issuance of new money is aligned with wealth creation.

Where would UK GDP be without banks issuing ever more money against the same buildings? Are we wealthier now our kids have to pledge to work longer for the same bricks their parents bought for less?

I don’t think so.

24. April 2016 at 10:20

Ironman, What does this mean?

“So income and expenditure in our economies being equal to the turnover of existing money and the change in debt.”

Suppose I write on a piece of paper that I owe my brother $20 trillion. At the same time he writes on a piece of paper that he owes me $20 trillion. Now we each owe the other person $20 trillion. This causes total debt in America to double. Does US GDP change? Or should we add up the sum of the absolute values of the net indebtedness of each person (which would be roughly zero for my brother and I)?

Philo, I’d guess that’s mostly debt at SOEs, which reflects political decisions. Probably lots of bad debt. Malinvestment.

Kevin, Why are the capital markets in California and NE not “liberalized?” I’m not quite sure what that means? In your comments it sounds more like the property markets are not liberalized.

24. April 2016 at 10:29

@ssumner

-Housing is a form of capital, is it not?

And I think China will trudge along fine with proper monetary policy, just as long as it doesn’t have too much foreign debt.

24. April 2016 at 10:34

Harding, Yes, housing is capital. But the housing market is not the capital market. The latter term refers to financial capital, not physical capital.

24. April 2016 at 11:13

No. More debt means more savings (or a shift from equity investing to lending). Does savings slow growth?

What if the borrowers waste the savings? Then the savings turns into consumption and growth would be no different than if the savers had consumed rather than saved.

What if the central bank creates new money and buys debt? This would not change the amount of debt, just the owners of the debt.

24. April 2016 at 11:31

Low debt is something akin to green-fields. Gross debt is a measure of entangled complexity of obligations. Its a tax on entrepreneurship/dynamism.

24. April 2016 at 11:34

As far as I know, Pettis’ arguments are not built upon Koo’s claim of monetary impotence. Pettis views debt vs. debt service capacity as a function of some measure of misallocation. The causality works from a gap between NGDP and “real” output capacity to increasing debt.

With respect to Richard Koo, he came up with a great book title, but his identification of monetary policy is pretty much change in money base, and he identifies effectiveness by private credit growth.

24. April 2016 at 12:02

So the SOEs wanted more capital, they couldn’t get it from the government (why not?), they couldn’t get it by issuing stock to private investors (they are and must continue to be wholly owned by the government), so they got it by borrowing from private investors. But this process will slow down of itself: private investors will become more and more reluctant to lend to such heavily indebted companies (whose profits are unimpressive). And since they were malinvesting this new capital, reduced borrowing will be good for the Chinese economy. Past malinvestment is, of course, bad, but there’s nothing here that even looks like a “problem” for the future.

24. April 2016 at 12:14

What malinvestments in China? I am sure there are a few, But, those cities which were ghost cities will be populated. Again, I bet China buys bad paper and loans keep coming:

https://www.bullionstar.com/blogs/koos-jansen/guest-post-5-chinese-ghost-cities-came-alive/

I mentioned you in an article at my name, Scott.

24. April 2016 at 14:19

Any thoughts on why the US and UK are so closely aligned in both graphs?

24. April 2016 at 14:34

@Jon – the drag effects of debt are strongly mitigated by the ease of bankruptcy.

24. April 2016 at 15:49

I think all else being equal higher debt reduces AD. Scott, you’ve talked in the past about how investing and saving is delayed consumption, and that it’s a good thing. That’s true, so the opposite, increasing debt to speed up consumption, is probably less good after the fact. More cash flow must be diverted from investing and saving to service the debt. That has to adversely impact AD. Now of course looser monetary policy would help increase AD to help offset this. Also, I think WHAT the debt is/was used for matters a great deal. If it’s used for investing in things like factories, infrastructure, education and other things that improve productivity (shifting AS to the right) then high leverage can be a good thing. Lots of young companies have negative equity due to being highly leveraged. A country like China could be adequately compared to something like this. China has to build up its capital stock and infrastructure in order to prepare to compete globally.

24. April 2016 at 15:57

What people forget about the People’s Bank of China is that it can print money and pay off debts. The debts evaporate and are replaced by yuan.

The PBOC can buy bad debts from banks and non-banks, and have before. They may be doing so now.

This can lead to inflation, but for the last several years China has actually been below its inflation targets.

The PBOC (or the CCP) is right: the real danger is money that is a little too tight, not money that is a little too loose.

24. April 2016 at 16:39

A, I do prefer Pettis’s arguments to Koo, although to be honest I haven’t looked at their arguments in detail.

Philo, I believe they are borrowing from state-owned banks.

Matthew, Perhaps both countries are responding to the same downward trend in global interest rates.

Anthony, I don’t see why interest payments reduce AD. Yes, someone has to pay the money, but someone else receives the exact same amount on the same day. The public as a whole doesn’t have less money.

24. April 2016 at 17:28

Does SOE borrowing from state-owned banks differ in any important way from the SOEs simply receiving funds direct from the government? By this “borrowing,” one state-owned entity becomes indebted to another state-owned entity: the state is lending to itself. (In your chart I assumed that “corporate debt” was the debt of private corporations, and that SOE debt would come under “government debt”: evidently that was wrong.)

24. April 2016 at 19:38

ssumner asks for an explanation of the following sentence written by another economist:

It’s a variation on the national accounting identity “Aggregate Demand = GDP + Net Change in Debt”

ssumner then asks a hypothetical question:

The answer is that no change to GDP has taken place because neither you nor your brother has created any money as part of that peer-to-peer transaction. Creating money through debt takes a third party, and by law, that means a commercial bank will be involved – it is a direct outcome from the accounting that happens whenever such a bank originates a new loan.

25. April 2016 at 03:05

“stimulating an unsustainable boom, and then leaving waste and wreckage behind which could have been used for sustainable projects.”

I always thought a natural part of Capitalism was that few/no projects should be entered into with any confidence of long term sustainability (as is) and that waste and wreckage will always be left behind… Mom always told me it would be tough out there in the real world.

“As far as I know, Pettis’ arguments” – Definitely worth reading him on current account balances. I found him by accident looking up something on currency, didn’t read all that much of him as China is of little interest to me, and anything good to say he is clearly “careful” to write about, but he is clearly a sharp guy who has spent a lot of time thinking about this. The fact he questions the benefits, to the US, of the dollar as the global accepted currency might bias me a bit in his favor.

25. April 2016 at 03:42

Oh look, here comes the ancient fiscal tautology brigade:

http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2011/04/is-modern-monetary-theory-modern-or-monetary-or-a-theory.html

25. April 2016 at 05:05

Philo, That’s a difficult question, as SOEs span a range of behaving much like a private company (think Singapore Air) to behaving much like a government organization (think Amtrak, or the Post Office.) In China, I believe the SOEs are under pretty strong government control, but also have some private sector characteristics. I can’t say exactly how much of each.

Ironman, You said:

“It’s a variation on the national accounting identity “Aggregate Demand = GDP + Net Change in Debt””

Not only is that not an identity, it’s not even true. Or else it’s a very weird definition of AD.

As for the rest of your answer, obviously one doesn’t need third parties to create debt. So when you say “debt”, are you excluding things like bonds, and only talking about bank debt?

derivs, Yes, I’ve read him on CA imbalances. I don’t see them as being much of a problem.

Ben, That was an excellent post by DeLong.

25. April 2016 at 05:14

Three mechanisms by which debt can harm growth:

(1) High debt crowds out investment. If loanable funds are relatively scarce, higher debt raises real interest rates and reduces investment.

(2) Higher (distortionary) taxes, either currently or in the future, to pay for the debt.

(3) Expectation of a future sovereign debt crisis and/or hyperinflation.

Oh, I just thought of one more:

(4) Since all of these imply a budget constraint on government spending, another effect of high debt levels is to reduce the government’s ability to use fiscal policy or bailouts to stabilize output in the future. The expectation of higher future volatility may reduce current investment.

(You may disagree with (4) because you don’t think that fiscal policy is ever necessary. But if people don’t know this, or if policymakers will not follow optimal monetary policy so that fiscal policy *is* still useful, then this effect will still occur.)

25. April 2016 at 07:22

Good perspective, Scott.

One missing item is the “open-ended” promises governments have made to citizens in the form of medical care and pensions. I think these are much more problematic for Western Europe than elsewhere.

25. April 2016 at 08:38

“As always, NGDPLT would make the debt crisis (if it does occur) much less severe.”

Scott, what do you mean by “less severe”? NGDPLT would seem to have the effect of extending the duration of any correction to bad debt and the mal-investment it caused. The shock may be less severe but the cure takes much longer.

We should never wish for a financial crisis but such events can provide material economic benefits. The most important being that financial stress in a free market system can reveal faulty economic valuations and help redistribute assets from poor managers to smart ones. An economy that never faces the stress of bad economic decisions is like a tree that never faces strong winds. The tree may look stout but in fact it is overgrown and brittle and actually fragile, doomed to topple when strong winds ever do blow.

The important question is not whether NGDPLT works. Rather it is whether NGDPLT can work in an economy where economic motives and consequences are skewed and distorted? And especially, whether NGDPLT can work when its policy mechanisms are the ones being exploited!

25. April 2016 at 10:20

Dan W.

“The most important being that financial stress in a free market system can reveal faulty economic valuations and help redistribute assets from poor managers to smart ones.”

This still goes on even with NGDPLT. Bad decisions will still lead to losses and good decisions are rewarded. The NGDPLT simply limits the risks of “contagion” and unnecessary (and unproductive) unemployment.

Think 2006-2007 in the US. The construction sector was contracting and bankruptcies were slightly up, but employment was still decent. Had the Fed maintained adequate growth of NGDP in 2008 and 2009, the adaptation process would probably have continued. The American public of 2016 would be much wealthier, the labor market would be tighter, interest rates would be higher and the government would be less indebted.

25. April 2016 at 11:37

“Anthony, I don’t see why interest payments reduce AD. Yes, someone has to pay the money, but someone else receives the exact same amount on the same day. The public as a whole doesn’t have less money.”

Defaults. Some amount of debt is always unpaid. This is why I think what the debt is used for matters. If it’s used for a cash producing investment then this is obviously better for borrower and lender than, say, a giant booze cruise. Sure the boat company and liquor distributors get paid, but the borrower defaults and the lender writes down the loan. The borrower then has future consumption crimped and the lender lost money. The higher the debt burden the greater the amount of defaults and the more harm is done to both borrower and lender.

25. April 2016 at 11:49

@Anthony McNease

“This is why I think what the debt is used for matters.”

Prof. R. A. Werner believes that the ‘man-made problem’ was the issuing of the ‘wrong’ type of credit. There is ‘productive’ and ‘unproductive’ credit.

“Importantly for our disaggregated quantity equation, credit creation can be disaggregated, as we can obtain and analyse information about who obtains loans and what use they are put to. Sectoral loan data provide us with information about the direction of purchasing power – something deposit aggregates cannot tell us. By institutional analysis and the use of such disaggregated credit data it can be determined, at least approximately, what share of purchasing power is primarily spent on ‘real’ transactions that are part of GDP and which part is primarily used for financial transactions. Further, transactions contributing to GDP can be divided into ‘productive’ ones that have a lower risk, as they generate income streams to service them (they can thus be referred to as sustainable or productive), and those that do not increase productivity or the stock of goods and services. Data availability is dependent on central bank publication of such data. The identification of transactions that are part of GDP and those that are not is more straight-forward, simply following the NIA rules.”

http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/339271/1/Werner_IRFA_QTC_2012.pdf

25. April 2016 at 11:50

Scott:

“As for the rest of your answer, obviously one doesn’t need third parties to create debt. So when you say “debt”, are you excluding things like bonds, and only talking about bank debt?”

IT doesn’t necessarily require a third party but your scenario does actually require $40 trillion in cash to exchange hands to be legal. That requires $40 trillion in base money I think. Ironman is right that the GAAP accounting required to legally book yours and your brother’s loans is more than just a couple of IOUs exchanging hands. Your $20 trillion, for instance, would need to be either completely self funded by yourself or you could borrow about 90% of it from depositors/bondholders.

25. April 2016 at 16:59

I would think it depends on what the debt is for. If a high percentage of debt is used to finance low ROI activities then it will slow growth.

If people are going into debt to finance business ventures that’s probably okay; to finance expensive second homes probably not so good. If a country is going into debt for welfare programs that’s probably not as good as going into debt to improve critical infrastructure.

25. April 2016 at 22:23

@scott

Real economic growth requires at least one of the following:

1. Deflation

2. Increased velocity of the money stock held by the non-financial sector, or

3. Increased indebtedness by the non-financial sector (or expressed more generally a decrease in the net amount of financial assets held by the non-financial sector.)

25. April 2016 at 22:24

Dan W said this: Scott, what do you mean by “less severe”? NGDPLT would seem to have the effect of extending the duration of any correction to bad debt and the mal-investment it caused. The shock may be less severe but the cure takes much longer.

Dan, if perfectly good assets are destroyed by a Fed who not only wants to take down bubbles but take down the economy and wages and everything, that is an unacceptable correction. Did you know that they did mark to market in the Great Depression and it didn’t work out so well? Talk about wanting to take a sledge hammer and destroy everything. It is called by me, anyway, Procyclical Craziness: http://www.talkmarkets.com/content/financial/central-banker-procyclical-craziness?post=92585

25. April 2016 at 22:29

@scott

Btw – I think this is just an accounting identity.

26. April 2016 at 03:32

Although you generally dismiss the “distress costs” theory of debt hurting the supply side, a lot of structural valuation models of firms as well as generally accepted managerial theory make a big deal out of those costs to a firm; i.e. a firm with more debt will have a tougher time competing than one without, ceteris paribus, and the function is non linear so it can look like the effect is small, until it isn’t.

I’m not sure about the quality of the literature supporting it, but lots of smart people take this as near axiomatic. That doesn’t mean it is right, but it is almost certainly nontrivial, and possibly significant enough to cause the supply side effect described.

26. April 2016 at 04:55

Jonathan, I agree on points 2 and 3, which relate to sovereign debt. Not sure how high levels of debt impact real interest rates.

Brian, If those are viewed as debt, then they can certainly be a problem.

Anthony, You said:

“Defaults. Some amount of debt is always unpaid.”

How does that answer my question? How do defaults reduce AD?

Carl, You said:

“If a high percentage of debt is used to finance low ROI activities then it will slow growth.”

But then it’s not debt that’s the problem, it’s low ROI activities. Those would be a problem even if financed by equity.

dtoh, You said:

“Real economic growth requires at least one of the following:”

No it doesn’t, even with all three failing to hold true, an increase in the money supply could produce RGDP growth.

Njnnja, I can see how heavy debt could hurt a firm. But I have trouble seeing how you scale that up to macro levels. Are there any periods of time when our macroeconomy was hurt by debt, while NGDP was doing fine? That might help me get a grasp on this issue. Perhaps there are some examples in Latin America–Brazil currently has a deep recession and high inflation.

26. April 2016 at 05:09

@scott

How can the money supply increase without an increase in indebtedness by the non-financial sector. (Fed doesn’t do helicopter drops.)

26. April 2016 at 05:39

Scott:

Re: higher debt raising real interest rates —

I’m talking about higher government debt as an alternative form of saving crowding out private investment in the loanable fund market.

Admittedly this does not happen in a simple model with lump sum taxes and Ricardian equivalence. In this case, higher debt would cause households to expect higher taxes in the future, and thus desired saving would increase by exactly enough to absorb the greater government debt.

If we move away from the Ricardian world, however, then crowding out can happen. For instance, in an OLG model higher public debt will lower investment, and therefore raise interest rates.

Of course, in reality it is not clear what the effect on interest rates will be, because (e.g.) the expectation of higher future distortionary taxes will lower the return on capital, which will lower real interest rates.

26. April 2016 at 06:49

Scott:

“How does that answer my question? How do defaults reduce AD?”

An individual or business in bankruptcy or coming out of it cannot spend, consume or invest the same way or level of someone with a sound balance sheet. It seems you’re asking me why a sound balance sheet matters and how a bad one can affect AD. I can relate my experiences working at one of the big banks during the crisis. You’ve mentioned here in past posts about how in mid 2008 NGDP expectations were plummeting. This is true, and one aspect of this, I think, may be due to balance sheet concerns both for businesses and individuals. We, the banks, didn’t know whose balance sheet was good or bad. Lending, even very short term lending, was severely curtailed. This had a very adverse impact on velocity. Consumers, worried about potential unemployment, stopped buying and started saving more cash for the impending rainy day.

Therefore I think the high debt, bad balance sheets and fear of defaults slows velocity for lenders, borrowers, investors and consumers.

26. April 2016 at 07:02

Speaking of Helicopter drops, does Kocherlakota understand them? I thought a Helicopter drop would be the issuance of base money, one time, with no treasury bonds being needed at all as collateral to the Fed. But that is not how Kocherlakota sees it: http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2016-03-24/-helicopter-money-won-t-provide-much-extra-lift

I think he doesn’t get it. Lonergan says treasury bond issuance is not the way it works.

26. April 2016 at 07:18

“Are there any periods of time when our macroeconomy was hurt by debt, while NGDP was doing fine? That might help me get a grasp on this issue. Perhaps there are some examples in Latin America”

I think Argentina and their dependence on foreign capital is a great example. It’s not a problem when NGDP is doing fine – payments are being serviced, the problem is when the economy goes sour and you risk being cut off from the funds you have committed to spend and planned next years expenses off of. As you have no source of funding and your intended expenses and past expenses have been partially funded by foreign capital, it appears you have little choice but to cut expenses (or print money – which in Argentina always =’s inflation).” Seems like AD has to get cut????

As for Brazil.. it’s problems go way way way beyond money supply… although watching commodities I wouldn’t be surprised if things start looking a bit rosier soon.

26. April 2016 at 10:22

Scott:

“But then it’s not debt that’s the problem, it’s low ROI activities. Those would be a problem even if financed by equity.”

That was my point. I don’t think debt is “generally” bad per se. And the difference between using debt or equity to finance a venture generally has to be evaluated the old-fashioned way: npv of the loan, opportunity costs, ROI and so on.

I use the qualifier “generally” because I do think equity financing is better than debt financing because NGDP can fluctuate wildly making NPV calculations exceedingly difficult and because I don’t believe that interest rates truly reflect the risks of default because too much debt is insured by market actors who are not subject to market discipline.

(I’m making this up as I go…). So, I would say debt levels are concerning to the extent the market is socialized (i.e. to the extent that credit prices are obfuscated by actors who loan backed by the credit of other people’s money).

26. April 2016 at 17:20

@scott

Or you can get this (http://www.zillow.com/homedetails/2806-Taliesin-Dr-Kalamazoo-MI-49008/74155600_zpid/)FLW House in Kalamazoo for $1 million less.

Why pay inflated Chicago prices?

27. April 2016 at 02:28

Excessive debt slows growth by the definition of excessive. I think Pettis is claiming that China’s debt has made their economy very pro-cyclical, but he is not currently predicting a crash. If there is one, Austrianism will briefly appear to be true.

27. April 2016 at 05:21

dtoh, Monetary policy and net indebtedness are basically unrelated. Just consider monetary policy in an economy with no debt. It’s perfectly easy for the money supply to increase without net indebtedness increasing.

Jonathan, In this post I am discussing total debt, not public debt.

Anthony, Why wouldn’t the central bank boost M to offset the fall in V?

dtoh, You know what I’m going to say . . . but then you’d have to live in Kalamazoo.

27. April 2016 at 05:44

What’s to say that further increases in M don’t simply result in being offset by further decreases in V.

27. April 2016 at 09:15

@scott

You said, “Monetary policy and net indebtedness are basically unrelated.”

In theory…maybe. But in practice no. You can’t increase the money supply without increasing net indebtedness. (Ignoring ER held a the Fed of course.) They are joined at the hip. Yin and Yang.

There is no such thing as monetary policy in an economy with no debt. It doesn’t exist.

Bottom line, in practice you can’t have real growth without increasing net indebtedness.

Probably more economists per capita in Kalamazoo than in Newton.

27. April 2016 at 10:33

Scott:

“Anthony, Why wouldn’t the central bank boost M to offset the fall in V?”

I think they would, but the question posed is “Does debt slow growth?” All things being equal, including monetary policy, I think it does at higher levels. I don’t envision the relationship is linear by any means.

Said differently, I think very high levels of debt require monetary expansion to achieve the same levels of NGDP growth.

27. April 2016 at 11:09

derivs. You asked:

“What’s to say that further increases in M don’t simply result in being offset by further decreases in V.”

Great! Then the Fed owns the world, and we can all retire.

Dtoh, It’s not really even debatable. After 2009 debt fell in the US while the money supply rose. QED.

http://www.businessinsider.com/america-is-not-drowning-in-debt-2013-4

And yes, you can have monetary policy in an economy with no debt, I’ve done many posts explaining how.

You said:

“Bottom line, in practice you can’t have real growth without increasing net indebtedness.

We’ve had real growth since 2009, so that’s wrong too. Or take Robinson Crusoe, couldn’t he boost output on his island, with no debt at all?

Anthony, But monetary expansion is costless, so I still don’t get why debt would reduce growth, at least in practice.

(I’d expect higher levels of debt to have no effect on V, or maybe even increase it.)

27. April 2016 at 13:20

Scott:

“(I’d expect higher levels of debt to have no effect on V, or maybe even increase it.)”

I can only speak from the effects we see in the banking industry. High levels of debt mean higher defaults. Higher defaults hurt the balance sheets of banks. The loan loss reserve methodology we are required to follow is procyclical. When losses are going lower, we have to release reserves which increases net income and frees up more capital for lending. When losses are increasing we have to build up reserves, lowering net income, and freezing more capital and lowering lending.

The effect on the consumer is more a factor of balance sheet repair and borrowing effects due to bad credit bureaus. When a consumer doesn’t pay back a loan they can’t borrow for seven years (generally speaking). Also they are probably reducing consumption or at least not increasing it.

27. April 2016 at 13:35

I should add, again, that I don’t think “debt reduces growth” accurately describes what I think. As stated before I don’t think the relationship is linear. It may even be close to a step function, because the real cause is increased default risk. Can monetary policy help alleviate that risk? I think so obviously (that’s why I’ve been here since Ramesh led me here way back in 2009). Higher NGDP expectations would have dampened the crisis.

Maybe a better explanation is that I think when NGDP expectations are going lower higher debt is worse than lower debt due to its effect on the banking and credit systems which are important tools in monetary policy.

Banks can increase V via lending due to fractional reserves, but conversely they can reduce V by pulling back lending when their balance sheets are hurt. So I think debt can actually increase growth in right amounts. Leverage, as China has done, can increase growth. However, I think at extremes the opposite effect logically occurs.

27. April 2016 at 19:05

@scott

I don’t think there is any getting around this, it’s an accounting identity.

For growth, you have to have one of the following:

1. Deflation

2. Increased velocity of the money stock held by the non-financial sector, or

3. Increase in the money supply (held by the non-financial sector) EQUALS Increased indebtedness by the non-financial sector (or expressed more generally a decrease in the net amount of financial assets held by the non-financial sector.)

Take a close look. I agree, it’s not debatable, AND I think your numbers are wrong because you are looking at total debt rather than indebtedness of the NON-financial sector.

28. April 2016 at 10:38

dtoh, Then give me the right numbers and I’ll show you are wrong. Look, you said this is an identity, which makes no sense unless you define money as debt, but money is not debt. You need to present an ARGUMENT, not just make an assertion. So far you haven’t given me any reason to believe a claim that you believe, but AFAIK, no economist believes. If it were truly an identity, don’t you think someone would have noticed?

It’s very possible for money to go up as debt goes down, for the simple reason that money and debt are different things.

28. April 2016 at 20:14

Scott,

No it is impossible. If we ignore money stocks held by the financial sector, there is no way for money to increase except through the exchange of money for financial assets with the non-financial sector. The Fed does not give the money away in OMP. It is always an exchange for debt (could be equity..but I assume that is not the argument you are making) and it always results in an increase in money and a decrease in financial assets held by the non-financial sector.

If I’m wrong and the Fed issues money without receiving debt in exchange, please let me know as I would like to be a counter-party to that trade.

29. April 2016 at 17:39

dtoh, You said:

“If we ignore money stocks held by the financial sector, there is no way for money to increase except through the exchange of money for financial assets with the non-financial sector.”

Not true, they could buy gold. But even it it was true it would not support your point.

You said:

“Real economic growth requires at least one of the following:

1. Deflation

2. Increased velocity of the money stock held by the non-financial sector, or

3. Increased indebtedness by the non-financial sector (or expressed more generally a decrease in the net amount of financial assets held by the non-financial sector.)”

That’s wrong because debt can be created or destroyed with no involvement of the Fed. The money supply and debt are two different things. Your mistake is like if someone had said in 1902 that gold cannot be sold without the money supply increasing. At that time an increase in the money supply involved the purchase of gold, but gold could also be sold to someone other that the monetary authority. Ditto for debt.

All you need is constant V, constant P and an increase in M. And rising M doesn’t require increased indebtedness by the private sector.

GE creates a bond and sells it to me. The amount of debt has changed, but not the money supply.

29. April 2016 at 21:41

@scott

1. The Fed does not buy gold and is not legally allowed to own gold.

2. You said, “GE creates a bond and sells it to me. The amount of debt has changed.”

No. Net indebtedness of the non-financial sector has not changed.

3. You said, “That’s wrong because debt can be created or destroyed with no involvement of the Fed. The money supply and debt are two different things.”

If you narrowly define money, then in theory, yes. You could have an increase in MB (less ER) and at the same time a repayment of debt by the non-financial sector to the financial sector in an amount greater than the increase in MB….. but that would of course result in a decrease in the broader monetary aggregates. And.. this is only a theoretical possibility…it would require that MB (less ER) be increasing, broader money aggregates be declining, and RGDP be increasing. In fact, this never happens.

4. Looking at this from a broader viewpoint than just an accounting identity, the result is not at all surprising. Growth typically involves the relinquishment of current consumption for a claim on future output, and as the economy grows, these claims increase. 150 years ago, these claims were typically the implicit ones of Farmer Jones to the output of his own fields. In a modern, specialized and efficient economy, these claims are more often effected and represented by debt obligations between unrelated parties and so a growing economy will result in increasing amounts of indebtedness.

30. April 2016 at 05:47

dtoh, You said:

“No. Net indebtedness of the non-financial sector has not changed.”

You can define things anyway you wish, but if this is not an increase in debt, then you are defining debt differently from everyone else. All debts are assets and liabilities, and hence by your definition the world would never have a debt problem. There is never any “net debt”. Again, you are free to use whatever definition you wish, but it has no bearing on this post, which defines debt in the ordinary way, and responds to other articles that define debt the normal way.