Did a supply shock cause the Canadian recession? And did tight money make it worse?

It appears the answer to both questions is “yes.” The real question is why this seems so counter-intuitive. This post tries to explain some stylized facts discussed recently by Nick Rowe. He pointed out that Canada went into recession during 2008-09, despite no banking crisis. And inflation stayed stable at about 2% despite a significant output gap.

I’ll argue that an adverse supply shock caused by the plunge in global trade reduced Canadian AS, and pushed Canada into recession. Then the Bank of Canada tightened monetary policy in order to hold inflation down to the 2% target.

Many would argue the opposite; that a fall in global trade reduced Canadian AD, and the Bank of Canada did an expansionary monetary policy that kept inflation up around 2%, which is their target.

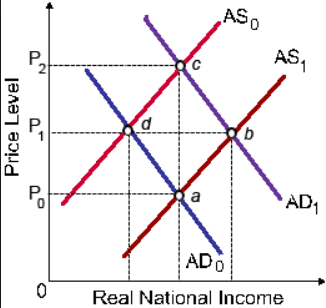

I wasn’t able to find a good AS/AD diagram, but this one will work, if we make a few assumptions:

1. Suppose we start with point b being the initial equilibrium; this is time=1.

2. Then Canada falls into recession, and both AS and AD decline at time=0. I.e. we reverse the graph’s dynamics.

3. Let the price level represent the rate of inflation. Hence steady prices on this graph imply a steady rate of inflation, at 2%.

In that case, Canada moved from point b to point d. Output fell but the inflation rate stayed stable. How can this be explained?

It turns out that the explanation is incredibly easy, incredibly straightforward. But only if you stop thinking like a Keynesian and start thinking like a market monetarist.

Let’s suppose that the BOC had been targeting NGDP in 2008, when global trade fell off a cliff. How would the Canadian economy have been affected? Many would see the drop in global trade as a demand shock hitting Canada, as there would have been less demand for Canadian exports. In fact, it would be an adverse supply shock. Even if the BOC had been targeting NGDP, output would have probably fallen. Factories in Ontario making transmissions for cars assembled in Ohio would have seen a drop in orders for transmissions. That’s a real shock. No (plausible) amount of price flexibility would move those transmissions during a recession. If the assembly plant in Ohio stopped building cars, then they don’t want Canadian transmissions. If the US stops building houses, then we don’t want Canadian lumber. That’s a real shock to Canada, i.e. an AS shock.

If the BOC had insisted on targeting NGDP, despite the huge drop in Canadian exports, then Canadian inflation would have risen. Canada would have moved to point c on the graph. A classic adverse supply shock. But they didn’t. The BOC targeted inflation. To keep inflation stable at 2% they had to reduce AD, which meant a tight monetary policy shifting AD to the left. This is why many economists support NGDP targeting; it makes output more stable when there are supply shocks.

I doubt that most people see the situation the way I do, even though the AS/AD model is quite clear, indeed given the fall in output and stable inflation, there’s not even any room for dispute. Both the AS and AD curves shifted left.

I think people disagree because they are affected by two common fallacies. In the comment section of the previous post John Papola pointed out that many people don’t understand that AS and AD shocks are basically real and nominal shocks:

The language of AS/AD may work well among economists who have a careful understanding of the distinction between monetary effects and real effects, but I believe strongly that it is difficult, even destructive, for non-economist readers precisely because nominal vs. real distinction becomes entangled. This is made worse by the fact that Keynesians explicitly discuss “demand” in terms of targeting real variables.

. . .

You said recently that macro students should only be taught two concepts: Say’s Law, and NGDPLT. I generally agree (even if I have concerns about NGDP being a sufficiently broad proxy for the flow of nominal spending). AS/AD doesn’t aid this understanding without it being HEAVILY caveated.

When the public hears about “demand”, they think about “consumers” buying stuff. They think about wrong-headed ideas like the often-repeated notion that consumers “drive” economic growth, rather than production and investment. They think about the Keynesian approach, which is all they hear. And the Keynesian approach rolls in with it the conflation between saving and hoarding that has plagued macro since Malthus.

I think John is on to something here. Most people think of AD in terms of the real quantity demanded, not a given nominal quantity of spending. As an aside, most economics students make the same mistake in basic supply and demand. They think the big boom in PC sales during the 1990s occurred because there was more “demand” for PCs. Consumers piled into the stores and bought more PCs. Of course economists know that the supply increased, reducing price, and increasing quantity demanded. The same is true at the aggregate level. The real shock hitting Canada in 2008-09 looked like a drop in AD, because real output fell. But we know that even if the BOC had targeted NGDP, output would have fallen. Targeting NGDP doesn’t magically make Ohio automakers want more Canadian transmissions. It doesn’t make American home-builders want more Canadian lumber. Yes, the Canadian dollar fell somewhat, but not enough to prevent a fall in exports.

Canada had a “reallocation recession.” Labor had to re-allocate out of declining sectors into other sectors—like Canadian home-building.

But the BOC then made it worse; they reduced AD to keep inflation from rising above 2%. Here’s where the other source of confusion comes in. Most people have trouble envisioning that the BOC ran a tight money policy. After all, they cut interest rates!! If you don’t know the fallacy of that assumption by now then GET THE HELL OUT OF MY BLOG.

The proof’s in the pudding. NGDP growth fell significantly; hence the BOC ran a tight money policy, at least tight relative to the policy that would have provided macroeconomic equilibrium. That is, they failed to provide a steady growth rate of NGDP; a policy that would have allowed labor re-allocation to occur in an accommodating environment.

Canada was hit by a double whammy; a reallocation recession, plus a demand shock recession. The net effect was a deeper than necessary recession, and no change in inflation. Still it could have been worse. Money wasn’t as tight as in the US and Europe.

Since then (former BOC governor) Mark Carney has become more receptive to NGDP targeting, and I’d guess for much the same reason that Nick Rowe has become more receptive. It seems like Canada could have benefited from more AD in 2009. But inflation targeting didn’t provide that signal. The NGDP data was sending a “warning, too little AD” signal loud and clear.

John’s pessimistic about the AS/AD approach:

Can we find a way to talk about these monetary issues that illuminates good policy without steering readers in the Keynesian cul-de-sac?

I’m less pessimistic. The problem John observes is just as common with ordinary S&D. Yet we don’t give up on that model. I’d suggest relabeling the AD curve as “NE,” meaning nominal expenditure. That might reduce the tendency to equate “AD” with “quantity of output bought and sold.”

This approach would also fit in with how we teach the “classical dichotomy.” Teach students how NGDP gets determined, and then teach students how changes in NGDP get partitioned between inflation and real output. That’s the essence of macroeconomics in a nutshell, but you’d never know it from the endlessly misleading Keynesian language.

Tags:

7. March 2013 at 12:24

Prof. Sumner,

I’ve thought of an excellent new project for the Market Monetarist community.

Right now, we have all these examples of countries that have pursued bad monetary policy (Ireland, Latvia, Greece, etc.) and countries that have pursued good monetary policy (Iceland, Israel, Switzerland, Poland, etc).

Someone should compare and contrast the various structural reforms that have been pursued in those countries since the financial crisis.

I know you believe that countries with low unemployment are more likely to pursue positive structural reforms than countries with high unemployment.

Don’t we have a big enough data set now to see whether that hypothesis is true?

7. March 2013 at 12:35

“. . . GET THE HELL OUT OF MY BLOG.” Lighten up, Scott! There are so many fools, you really should just suffer them gladly.

7. March 2013 at 12:38

(But you weren’t serious, were you?)

7. March 2013 at 12:41

Scott

You´re accused of spreading the ADD (aggregate demand disorder) virus! And John Papola seems to be the first identified victim:

“Papola is a master communicator and an outstanding artist. But I fear he is at risk of coming down with ADD (Aggregate Demand Disorder). So far, his most outstanding creations (his videos, as opposed to his articles and blog comments) don’t seem to bear any significant trace of ADD, which is why they are so powerful. But it would be a shame if his critiques of Keynesian economics were themselves to become subverted by typically Keynesian notions.”

http://bastiat.mises.org/2013/03/fighting-keynes-with-keynes/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+MisesBlog+%28Mises+Economics+Blog%29

7. March 2013 at 12:41

Very nice blogpost. Thank you.

It seams to me the canada example is a fantastic example how a inflation target messes up relative prices. Canada seams to be a really good example also because there was not much going on, no huge debt, no euro, no housing bubbble nothing like that, just a inflation target and a supply shock.

7. March 2013 at 12:49

@marcus nunes

Nice find with that article its quite funny. I kind of think that the AS/AD model should only be used with people that allready understand the microeconomic concepts that are at work. Once one has a proper understanding of the price system, how investment works talking in a AS/AD sence is just a short way of saying something.

Its quite intressting that I made the same development as Papola, I became intressted in economics really only after I saw his videos. This had set me on a path of inquery, trying to understand both keynes, hayek and the modern schools that build on them. It seams that me and Papola have both ended up at the exact same place. He and I both seam to favor a 0% GDP target.

7. March 2013 at 12:56

Scott

Inflation, as always, clouds the picture and that´s probably the main reason you advise not “uttering the I word”. But the term is imbued in official thinking no matter the degree of “dovishness” of the thinker. This is an example from 2 years ago:

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2011/05/04/a-%E2%80%9Csimple%E2%80%9D-answer/

7. March 2013 at 12:58

Marcus Nunes,

Great stuff!!

7. March 2013 at 13:02

The no-data claim that Canada had a “reallocation recession” isn’t, well, supported by the data. I’ve done some research on flows between industries and occupations in the US/Canada over recessions and the view simply isn’t there. Reallocation declines in recessions.

7. March 2013 at 13:16

Travis, Yes, someone might want to do that. I don’t know what they’d find.

Philo, Yes, joking.

Marcus, Perhaps people should use “protection” while reading this blog, so they don’t come down with a “virus.”

Andrew, Perhaps I should have said Canada would have had a re-allocation recession with sound monetary policy. You are right that I didn’t look at the data. It’s quite possible that tight money caused most of the unemployment.

7. March 2013 at 14:37

For NGDPT to outperform IT don’t you need a supply shock with inflationary not deflationary effects?

You are saying that as a result of the decline in demand for some Canadian exports the structure of demand changed In the economy . You categorize this as a supply shock. If the BoC maintained NGDP on trend then the result would have been lower RGDP and higher inflation than before the shock. Why would IT have led to a worse outcome than this ? The decline in demand for exports would have applied deflationary pressures to Canada. IT targeting would addressed this and brought RGDP to its max level with the targeted inflation rate but lower NGDP than before (due to changed demand structure). NGDPT would have increased NGDP beyond that point with higher inflation the result.

In this scenario (falling AD combined with a change in the structure of demand) IT actually seems better than NGDPT.

7. March 2013 at 14:39

Scott,

I see your point. But would you say that the current recovery in US vehicle sales and US housing starts is a positive supply shock for Canada? And, to address Nick’s question, is what is putting downward pressure on Canadian inflation right now?

Stronger US demand definitely seems like a positive AD shock for Canada. If the economy were operating close to its productive capacity, a surge in US vehicle and housing sales would put upward pressure on wages and prices in Canada absent tightening from the BoC.

So why would a drop in US AD be a negative supply shock for Canada but a recovery in US AD be a positive demand shock? Is it simply because the negative shock happened to quickly?

7. March 2013 at 14:54

[…] See full story on themoneyillusion.com […]

7. March 2013 at 15:31

Scott: “Since then (former BOC governor) Mark Carney has become more receptive to NGDP targeting, and I’d guess for much the same reason that Nick Rowe has become more receptive. It seems like Canada could have benefited from more AD in 2009. But inflation targeting didn’t provide that signal. The NGDP data was sending a “warning, too little AD” signal loud and clear.”

I’m not sure if your guess is right for Mark Carney, but it’s right for me. If you look at the 3 graphs in this old post (total CPI, core CPI, and NGDP) http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2013/01/the-bank-of-canadas-success-and-failure.html

you see no signal of the recession in total or core CPI, but a very obvious signal of the recession in NGDP. Those 3 graphs were my tipping point for supporting NGDPLPT for Canada.

We know that inflation targeting failed in Canada, but we still don’t really know why it failed (i.e. why we had a recession *despite* the BoC keeping inflation on target). Maybe your explanation (if your trading partners go partially belly-up, that’s a real/supply shock) is right. But there’s also the possibility that inflation targeting itself made the SRAS curve very flat. Or that inflation targeting created a longer lag.

I’m still thinking about this. Thinking about David Beckworth’s graph of the 1930’s, and about canoes and supertankers in the Phillips Curve.

7. March 2013 at 16:05

Its not really true to say “But the BOC then made it worse; they reduced AD to keep inflation from rising above 2%.”. It increased AD to hit the inflation target but did not increase it sufficiently to keep NGDP on its previous trend.

The explanation of a supply-shock caused by export problems seems more complicated than it needs to be.

If the global economic situation made Canadian businesses less inclined to invest, this would reduce the demand for labor. If wages are sticky then hitting the inflation target could still leave total total employment level (and RGDP) lower than before. NGDPT would have been better but even that might have led to lower RGDP if the demand for labor fell sharply enough.

7. March 2013 at 16:17

There were a bunch of commenters arguing in the comments of this AS explanation post( 2009 ), might have been on to something. http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2009/04/the-bank-of-canada-says-quantitative-easing-if-necessary-but-not-necessarily-quantitative-easing.html

7. March 2013 at 16:31

This is great.

Looking at NGDP, I always just *knew* in my gut that the BoC was too tight. But I could never properly work out the dynamics in my head, since I was viewing the Canadian recession as an AD shock. But you might be right: it was external AS. You see, I always thought the BoC just wasn’t easing *enough*, that they were too tight — but that they were still easing nonetheless. But no, maybe the signal was wrong: BoC was actually tightening!

It’s like working in a lab and finding out your equipment hasn’t been properly calibrated the whole time.

This requires some more thought. Something for me to think about the next little while.

7. March 2013 at 17:15

Thanks Scott. This explains a question I’ve had for two years. Back when I looked into the Sweden vs Denmark/Finland story, I was puzzled as to why inflation remained so buoyant in Denmark and Finland, despite collapsing money supply and nGDP. It might be a tad too tautological, but it would seem the broader world recession would hit those economies on the AS side, just as with Canada, maybe more so.

Also, if anyone would like to help me out, I want to add a monetarist counter to this Wikipedia page:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zero_interest-rate_policy

7. March 2013 at 17:50

Ron, You said;

You are saying that as a result of the decline in demand for some Canadian exports the structure of demand changed In the economy . You categorize this as a supply shock.”

Yes, but only because I don’t think I have any choice. If it were a demand shock then expansionary monetary policy could have offset the effects on output. But that seems really far-fetched. If someone wants to make that case I’ll gladly debate it.

Are you saying point d on the graph above is better than point c? If so, I strongly disagree.

Gregor, It might be a positive supply shock (although recall that with re-allocation it is not necessarily symmetical). In that case it would lower inflation.

You said;

Stronger US demand definitely seems like a positive AD shock for Canada. ”

The whole point of this post is that it isn’t what it seems.

Nick, I have a couple observations:

1. I’m inclined to think the flat SRAS is not the whole story, at least in the US. We have seen a signficant fall in wage growth, which indicates the AS curve is upward sloping. I will admit that wage growth has now fallen fairly close to the zero bound, and hence the SRAS curve may be fairly flat now, but in 2008 there was a significant amount of room for wage growth to slow.

2. I feel pretty strongly about the global trade shock argument, although I can’t quite put into words why I feel this way. I do know that Canada is closely integrated into the global economy, with exports being a pretty big share of GDP. To me it defies common sense that global trade could collapse in late 2008 without affecting Canadian GDP. But that’s just my intuition, and perhaps I’m completely wrong. What do you think? Could those lost export jobs have been quickly made up in other sectors? Don’t get me wrong, I think the fall in NGDP made the recession worse, but at least a mild recession seemed almost inevitable in late 2008.

I might also be influenced by what happened in the US. I definitely feel the US would have faced stagflation in 2008-09 if we had done NGDP targeting.

Ron, You said;

“It increased AD to hit the inflation target but did not increase it sufficiently to keep NGDP on its previous trend.”

No, I’m saying it reduced AD.

If output falls and inflation stays constant, then both AD and AS had to shift left, didn’t they? What other plausible explanation is there?

Thanks 123, I’ll take a look.

Thanks Sina, This stuff is very counterintuitive. I suppose even I thought in terms of negative AD shock at first. It wasn’t until I’d worked through the implications that it became clear that there was a real shock, And I still think the global trade channel is the most likely real shock.

7. March 2013 at 18:03

123, It’s interesting that Stephen Gordon ends up seeing it as a supply side recession, despite using what I view as faulty logic (the assumption that the decline on demand for Canadian exports was a demand shock to Canada.)

On the other hand I’d guess 99.9% of economists would agree with Gordon.

Justin, Good observation.

7. March 2013 at 18:37

“If output falls and inflation stays constant, then both AD and AS had to shift left, didn’t they? What other plausible explanation is there?”

I do believe AS shifted (due to uncertainty reducing the desire to invest) and if that is all that happened then the new equilibrium price level would have been higher than before and IT would have been a bad idea. But if the AD effects on the price level were greater than AS effects then IT would have moved the money supply in the right direction (just not as far as NGDPT would have).

However IMO the real issue isn’t the supply shock itself – its that the combined AD and AS changes led to the new equilibrium real wage rate being so far below the nominal wage rate that hitting the IT target still left real wages too high. NGDPT might have done the job but its still not guaranteed.

A change in the AS curve hides changes in relative prices. A shift in the AS curve could lead to a higher price level but mask the fact that real wages need to fall (because the demand of labor has fallen due to business uncertainty).

In this case (if wages are sticky) then a leftward shift in AS can lead to falling RGDP and some inflation.

7. March 2013 at 19:12

Can someone explain to me how a reallocation causes an increase in the overall price level? If the US demand for Canadian lumber falls, so much so that lumber producers have to seek jobs elsewhere, I can see how that might increase structural unemployment temporarily, but it isn’t obvious to me that this would put upward pressure on the price level. Lumber prices fall, other prices might rise, how do you determine which wins out in the aggregate?

7. March 2013 at 20:53

The terms of trade played a large role in the AS shock. Because Canada exports a lot of commodities, changes in the terms of trade tend to have a much bigger impact than in the United States. When there’s a big shift in the terms of trade, as occurred from 2008Q3 to 2009Q2, there’s going to be a big difference between policies that target consumer prices or nominal consumer spending and policies that target GDP prices or nominal GDP.

From 2008Q3 to 2009Q2, Canada’s GDP implicit price (i.e., the price index for the goods & services that Canada produces) fell 4.4 percent, whereas the price index for final domestic demand (the goods & services that Canada consumes) increased 0.4 percent — a five percentage point deterioration in the terms of trade. Because the shift in terms of trade reflected changes in international relative prices, outside the control of Canadian monetary policy, real consumption would have to fall regardless of how Bank of Canada responded. The changes in relative prices had to lead to reallocation of resources out of commodity-producing sectors.

7. March 2013 at 23:27

Has anyone thought to compare Canada’s experience with Australia’s? Any evidence of an AS shock in the Aussie data?

8. March 2013 at 05:23

[…] Nunes, Nick Rowe, Scott Sumner and some others have had an interesting discussion on the puzzling lack of disinflation, despite an […]

8. March 2013 at 05:35

[…] Sumner has a follow-up post on Nick Rowe’s post about whether a supply shock or a demand shock caused the Canadian […]

8. March 2013 at 05:45

I hope “123” who commented above will choose a different name, because I am the real 123 here. The only consolation is that the comment itself was good.

8. March 2013 at 05:55

[…] Sumner has a follow-up post on Nick Rowe’s post about whether a supply shock or a demand shock caused the Canadian recession […]

8. March 2013 at 06:09

Scott,

I said: “Stronger US demand definitely seems like a positive AD shock for Canada. If the economy were operating close to its productive capacity, a surge in US vehicle and housing sales would put upward pressure on wages and prices in Canada absent tightening from the BoC.”

You said: “The whole point of this post is that it isn’t what it seems.”

Apologies for being dense – I think understand your reallocation point in the crisis. But if the economy begins at full employment and US demand for autos surges, I don’t see how that puts downward pressure on Canadian price level (holding NGDP constant). Surely the Canadian auto and auto parts manufacturers will try to add more workers at current wage rates but find that other auto manufacturers are trying to do the same, resulting in a smaller increase in hours worked than would have been the case at the initial wage rates and an increase in wages and prices, ceteris paribus. And if the shock results in a increase in real output and upward pressure on prices absent any change in monetary policy (NGDP) is that not an a positive AD shock? To argue that it is a positive AS shock I think you would have to explain where how Canada sees downward pressure on wages and prices from the increase in US demand.

8. March 2013 at 06:38

Nominal demand can be found here, per sector, in great detail: http://www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/2013/pdf/gdp4q12_2nd.pdf, based upon the fundamental macro equation Y+Im = C+I+O+Ex

The point is however that in factories and farms and even offices, productivity often is ‘real’. And people also buy real stuff – which means that companies have to sell real stuff. Which yields real jobs (Okun’s law:http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=40236.0)

In the real world, transactions are of course nominal and the fundamental macro equation only follows from the accounting relations imminent in our economic system when we look at these nominal transactions. But labour and production are, unlike profits, real things. If real production doesn’t increase, real employment won’t, either. Or do you know a counterexample, i.e. a country were real productivity per hour declined from business cycle peak to businenss cycle peak?

8. March 2013 at 08:58

Very good post. While the AS-AD model is a very good model, perhaps it really should be called something else. I remember someone suggested Nominal Expenditure – Real Output (NERO) some time ago on this blog. Thinking in those terms makes it really easy to see.

I also think your point about NGDP being what really matters (as opposed to inflation) is very important here

The problem is that macro models (at least the ones I’m taugt) assume that people don’t like inflation and output instability. This logic leads to a trade-off between inflation and output in the case of supply shocks.

“Can someone explain to me how a reallocation causes an increase in the overall price level? If the US demand for Canadian lumber falls, so much so that lumber producers have to seek jobs elsewhere, I can see how that might increase structural unemployment temporarily, but it isn’t obvious to me that this would put upward pressure on the price level. Lumber prices fall, other prices might rise, how do you determine which wins out in the aggregate?”

-Procrastinator

Nick Rowe has a very good post on exactly this, that you just reminded me of:

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/03/teaching-sras-shocks.html

8. March 2013 at 12:42

[…] Rowe, Scott Sumner and Lars Christensen have been debating whether Canada was subjected to an AD or an AS shock or, […]

9. March 2013 at 07:21

Procrastinator. I discussed that in a newer comment section. If NGDP is unchanged and output falls, prices must rise in net terms.

Brent, Thanks. If that data is correct then it changes everything. I’d then say there’s little evidence of an AS shock in Canada

123, Yes, will the imposter 123 please change his or her name!

Gregor, You said:

“And if the shock results in a increase in real output and upward pressure on prices absent any change in monetary policy (NGDP) is that not an a positive AD shock?”

Is there a typo there? Both RGDP and P cannot rise if NGDP is stable.

Merijn, I don’t understand why you would use that equation. Why not just look at nominal output?

Asco, I agree that AS/AD is a horrible name.

9. March 2013 at 16:10

Scott said, “If that data is correct then it changes everything. I’d then say there’s little evidence of an AS shock in Canada”

The Canadian GDP implicit price deflators are available from the Statistics Canada CANSIM database here.