Creationism at the New York Times

The New York Times does not believe in creationism. They believe in evolution. They look down their noses at people who do believe in creationism. But when it comes to the social sciences, the Times believes in creationism, that is, they believe in theories that appeal to kindergarden-level intellects.

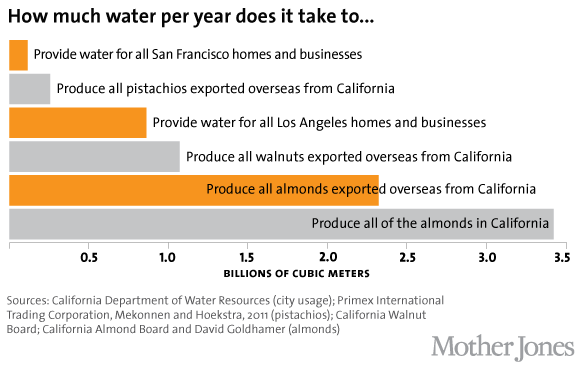

One of those “theories” is the idea that California faces a severe water shortage because lots of people have moved to an area with a dry climate. All thoughtful economists (on both the left and the right) view this theory as being preposterous. The California water shortage has almost nothing to do with population growth. Roughly 80% of the water is used by farmers, who squander vast quantities of water each year by employing extremely wasteful irrigation techniques in order to export crops like almonds. And that occurs because the price at which water is sold to farmers is absurdly low. Period. End of story.

This is EC101 economics, and I’ve never met an economist who did not understand this problem. But the Times can’t be bothered to talk to economists, they rely on historians:

“Mother Nature didn’t intend for 40 million people to live here,” said Kevin Starr, a historian at the University of Southern California who has written extensively about this state. “This is literally a culture that since the 1880s has progressively invented, invented and reinvented itself. At what point does this invention begin to hit limits?”

California, Dr. Starr said, “is not going to go under, but we are going to have to go in a different way.”

That makes about as much sense as the Times asking a Christian fundamentalist preacher whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded.

The Times is a relatively good newspaper. But to reach the elite level of papers like The Economist, they need to become familiar with good economic research. And that means figuring out what economics is capable of telling us about the world, and what it cannot. Economists don’t know how to solve very many problems. But one of the very few we do know how to solve is the California water shortage. Instead the Times is more likely to ask economists to explain complex problems like unemployment, financial instability and inequality, issues where we are not very strong.

The problem is simple to explain and (in a technical sense) simple to solve. Of course the politics are complex, and thus far have prevented a solution. However, even dysfunctional California will eventually have to work out a political compromise.

PS. The water used in irrigating just that portion of California’s almond crop that is exported is more than twice as much as the entire water consumption of San Francisco and Los Angeles combined. The New York Times should be ashamed of itself.

PPS. Steven Johnson has an excellent reply to the above quote about “Mother Nature.”

First of all, Mother Nature didn’t intend for 2 million people to live on Manhattan Island either. Mother Nature would also be baffled by skyscrapers, the Delaware Aqueduct, and the Lincoln Tunnel. Anyone living anywhere in the United States”Š”””Šapart from the most radical of the off-the-gridders, most of whom are probably in northern California anyway”Š”””Šis dependent on a vast web of human engineering designed specifically to mess with Mother Nature’s intentions.

The question is whether that engineering is sustainable. What the Times piece explicitly suggests is that California has been living beyond its means environmentally. That’s the point of those extraordinary overhead photographs of lush estates, teeming with greenery, bordering arid desert. You see those images and it’s impossible not to feel that something shameful is happening here. And yet, picture a comparable view of Manhattan sometime in the depths of January, with a thermal imaging filter applied. The boundary between Man and Mother Nature would be just as stark: frigid air surrounding artificial islands of heat. It’s true that New York City distributes that artificial heat much more efficiently than the rest of the country, thanks largely to its density, but it’s still artificially engineering your environment, whether you want to make a dry place wet, or a cold place warm. And while the Northeast has an advantage over California in terms of rainwater, California has a decided advantage in terms of temperature and sunlight, particularly the coastal regions where almost all the people live. Coastal California enjoys one of the most temperate climates anywhere in the world, which allows its residents to consume far less energy heating or cooling their homes. California is dead last in the country in terms of per capita electricity use. Thanks to the state’s abundant sunshine (and pioneering environmentalism) there are more home solar panels installed in California than in all the other states combined. If you’re trying to find a sustainable place for 40 million people to live, there are plenty of environmental reasons to put them in California.

Tags:

8. April 2015 at 08:44

Yglesias had a good discussion of this:

http://tinyletter.com/mattyglesias/letters/just-another-thing-to-blame-on-farmers

8. April 2015 at 09:11

-I’ve never understood why The Economist has this reputation.

8. April 2015 at 09:36

Matt, I’m not surprised that Matt beat me to it.

E. Harding. In the kingdom of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.

8. April 2015 at 09:41

Thank you for this clarifying note.

8. April 2015 at 10:06

Scott, I like the article, agree with the point, and appreciate that you spend your time making it. One issue that you touch on that I haven’t seen addressed much is rooftop solar. As far as I can tell, the model there should be just as outrageous to economists.

Retail residential electricity is priced far above marginal costs – usually priced over 10 cents when MC are about 4 cents per kWh (but California prices into the 40 cent range). The reason for the discrepancy is the grid/fixed costs that are bundled into the kWh price. The “right way” to price was recognised as far back as 1946 by Ronald Coase who recommended a multi part tariff. Today most industrial electricity is priced this way (a kWH charge close to the MC, a fixed customer charge, and a demand charge), but almost no residential prices are like this.

California allows rooftop solar to be compensated at the retail rate – far above MC. You can buy large-scale solar plants for 5-6 cents while small rooftop systems are 9-10 cents or more. But just like the problematic pricing of water incentizes inefficient farming, the improper pricing of residential electricity incentivizes building rooftop solar over large-scale solar (or traditional brown power)

Anyway I’d be interested in your thoughts on this. As well as the implications this has on the Pigou club (if the price of electricity is already 5 cents or more above MC, if the carbon / pollution externalities are less than 5 cents per KWh, is there any justification for a carbon tax on residential electricity?)

8. April 2015 at 10:22

I think this article has been ridiculed by both left & right pundits more than any article in recent memory.

I do however sympathize with Governor Brown. Despite the fact that the allocation of water in the state makes no sense, these water rights have been the way they are for decades and have been written into many contracts. You cannot just change these things at the drop of a hat. He does concede that if the drought persists and this becomes the new normal things will have to change.

Maybe I’m becoming too much of a realist and not enough of an idealist, but that position seems fair to me. If this drought brings about a major rewrite in the water rights laws, then at least something good will come of it.

8. April 2015 at 10:32

Scott is right: it would be optimal to charge farmers some kind of water tax to bring consumption back into equilibrium rather than give away a vital natural resource for free but… Liberal Roman is also right.

Water rights legislation would be a political death sentence and Brown knows it. On the other hand, it’s relatively easy to convince people that growing food is more important than watering their lawns.

8. April 2015 at 10:38

Kindergarden-level intellects like Plato, Aristotle, Avicenna, Maimonides, Thomas Aquinas, Kierkegaard, &c. You know, the slow kids.

8. April 2015 at 10:47

Liberal, Yes, but there is absolutely no conflict between what you write and what I wrote. There is the question of what causes the problem, and the different question of which solutions are politically feasible.

Either way, the NYT story is a complete embarrassment. They did not address either issue.

Randomize, You said:

“On the other hand, it’s relatively easy to convince people that growing food is more important than watering their lawns.”

That’s the problem, we need to tell the public that we can do BOTH. The solution is simple, just make farming a few percentage points more efficient that the current obscenely wasteful use of water. The Central Valley will be an agricultural powerhouse either way.

Thomas, What was Plato’s view of the California water shortage? How about evolution?

8. April 2015 at 10:52

Mark, I oppose carbon taxes on electricity, they should be imposed on specific fuels. I’m not knowledgable enough about the California electricity situation to comment, but what you say certainly seems plausible.

8. April 2015 at 10:55

Oh, the Times is getting pretty bad on the harder sciences too…

http://www.realclearscience.com/blog/2015/03/maybe_nyt_should_stop_writing_about_science.html

8. April 2015 at 12:04

I can’t tell whether Thomas is a creationist or merely a person who sees nothing wrong with sharing beliefs regarding Biology with intellectuals who lived in 400 BC.

8. April 2015 at 12:31

Mark, my fellow energy economist! Preach the good word!

8. April 2015 at 13:21

Jim, Good article.

8. April 2015 at 15:08

Here’s an op ed in the Sacramento Bee that talks about how the ground water pumping in western Central Valley is being used for the almond and pistachio farms and how a billionaire owns the biggest almond farm and packing facility in the state.

http://www.sacbee.com/opinion/op-ed/soapbox/article17332904.html

Thanks to lobbying from the agricultural interests, farmers will not have to curtail their ground water use until 2040.

8. April 2015 at 16:23

@ssumner

What does the California water shortage have to do with the creation of the universe?

8. April 2015 at 17:09

Excellent blogging. Back in the 1970s there was also a spate of articles about this very same topic. Some notice was paid to California’s rice farmers who flood their fields.

Someday American taxpayers and rate payers will wake up to the fact that urban America heavily subsidizes rural America, particularly through the auspices of the federal government.

Water projects, power projects, telephones, internet, mail service, airports, train service, all subsidized.

Rural America is a vast Pink-o Wonderland financed by urban taxpayers.

How about ethanol? What would be the reaction if President Obama suggested a program that converted urban wastes into ethanol and employed hundreds of thousands of urban workers in urban factories and was subsidized and mandated by law?

Switch switch the words “rural” and “urban” and you have a description of the modern-day ethanol program.

8. April 2015 at 19:11

The market solution for water is to simply auction water off to the highest bidder.

8. April 2015 at 19:35

I banged out this video last night, which was very similar to your take Scott. Instead of creationism,I used an analogy of putting people into orbit with catapults, and the media only occasionally asking physicists what they thought of this procedure.

8. April 2015 at 20:29

So Sumner is in favor of people in Arizona, many of them ‘snowbirds’ from Chicago, planting and watering bluegrass on their lawn instead of having gravel or native vegetation? After all, if they can pay for the water, why not? As for nuts, indeed they are being subsidized, which undercuts Sumner’s argument. Seems Sumner is nuts on environmental footprint as well as the benefits of monetarism.

8. April 2015 at 20:50

There’s another point too that Sumner overlooks: the social nature of capitalism. As Nobelian Elinor Ostrom points out in her works, people are not robots as MF would say, and in cases of a potential “Tragedy of the Commons” they do NOT behave as free-market ideology theory would suggest, where it’s every person for themselves since no property rights exist, but rather cooperation can result to wisely husband resources. (That’s a big sentence, will our ruddy-faced readers understand it?) Hence, when I was in Los Angeles during the early 1990s drought, a neighbor actually banged on my door and not-so-politely ‘shamed me’ by reminding me I was wasting water (which I was). I did cut back, so as not to disturb them, no use making enemies over something essentially trivial. The social aspect of capitalism is something entirely overlooked by ivory-tower Sumner.

8. April 2015 at 20:55

@myself- just to be clear –since we have a hostile audience here which simply does not want to listen to other viewpoints–the NY Times article on wasting water in California is like my meddling neighbor knocking on my door to remind me I’m wasting water. It serves a useful social purpose in helping to conserve water.

8. April 2015 at 21:11

The NY Times is chronically fact-deprived these days.

Remember the measles outbreak? Here’s what the Grey Lady has to say:

“The vaccination controversy is a twist on an old problem for the Republican Party: how to approach matters that have largely been settled among scientists but are not widely accepted by conservatives.”

Meanwhile, here are what the facts had to say:

“Across San Francisco Bay in Berkeley, the rates are more egregious at a facility associated with Pixar. Only 43 percent of children there are immunized, with 2.3 percent claiming a personal belief exemption.”

http://www.wired.com/2015/02/tech-companies-and-vaccines/

8. April 2015 at 21:12

Mark, Randomize,

The case for taxing electricity is even weaker than you mention. All of the following are likely keeping electric rates at or above “marginal social cost” and well in excess of marginal private cost:

-Costs and inefficiencies associated with regulation (including Averch-Johnson, and upstream regulation of primary fuel markets, such as coal, nat gas etc.)

-Any remaining monopolistic characteristics of utility service provision;

-Inefficient, but already existing expenditures on mitigation/control ;

-Inefficiencies and subsidies in demand-side management programs required by regulators.

-Utilities as tax collectors (can be 20%+ cost-of-service)

Lifeline subsidies to low income.

-The net metering or purchase of non-firm customer generated power (e.g. excess solar) at firm, all-on “flip-the-switch” retail prices instead of, as you mention, true avoided cost.

The Pigouvian tax has already been more than collected. We are likely underproducing electricity!

8. April 2015 at 22:40

It’s important to eliminate all water consuming ag in Ca.

and stuff more people in the wonderful metro areas!

9. April 2015 at 03:24

Am I missing something? They do address the issue and they do talk to an economist in the article.

“The governor’s executive order mandates a 25 percent overall reduction in water use throughout the state, to be achieved with varying requirements in different cities and villages. The 400 local water supply agencies will determine how to achieve that goal; much of it is expected to be done by imposing new restrictions on lawn watering. The 25 percent reduction does not apply to farms, which consume the great bulk of this state’s water.

State officials signaled on Friday that reductions in water supplies for farmers were likely to be announced in the coming weeks, and there is also likely to be increased pressure on the farms to move away from certain water-intensive crops “” like almonds.

…

But even a significant drop in residential water use will not move the consumption needle nearly as much as even a small reduction by farmers. Of all the surface water consumed in the state, roughly 80 percent is earmarked for the agricultural sector.

“The big question is agriculture, and there are difficult trade-offs that need to be made,” said Katrina Jessoe, assistant professor of agricultural and resource economics at the University of California, Davis.”

9. April 2015 at 03:55

Also, this is only one article from a series of articles called The Parched West as explained right at the bottom

It goes further into agriculture in an article printed the next day.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/06/science/beneath-california-crops-groundwater-crisis-grows.html

9. April 2015 at 05:03

Thanks Gordon.

Thomas, You asked:

“What does the California water shortage have to do with the creation of the universe?”

I should think that is obvious. Had the universe never been created, we wouldn’t be dealing with this water crisis.

Ray, That’s what I thought you’d say. I would have been very disappointed if you had criticized the loony NYT article. You are still batting 1000.

Steve, But you don’t understand. The NYT defines “conservative” as someone with loony views.

Eric, 60% agriculture and 40% urban sounds about right to me.

Edwin, After completely mischaracterizing the problem for 80% of the article, they say a few random sensible things at the end. But they never explain that this problem is caused by price controls, not “Mother Nature.”

9. April 2015 at 06:21

It’s not only the NY Times, I’d say that about 99% of the economics reporters employed really aren’t qualified to write on the subject. Even at the WSJ;

http://www.wsj.com/articles/gileads-1-000-hep-c-pill-is-hard-for-states-to-swallow-1428525426?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTWhatsNewsCollection

———quote———

State Medicaid programs spent $1.33 billion on hepatitis C therapies through the third quarter of last year, or nearly as much as the states spent in the previous three years combined, a Wall Street Journal analysis of federal data shows.

The growth was primarily driven by Gilead’s Sovaldi, a highly effective therapy that has a wholesale cost of $84,000 per person over the course of treatment, or $1,000 per pill. The price has sparked an outcry from insurers, members of Congress and others worried about the cost of treating an estimated three million Americans with hepatitis C, which can lead to cirrhosis or cancer of the liver.

….

These barriers to treatment have sparked local disputes about coverage, with officials pleading budgetary constraints and doctors complaining that economic considerations are trumping medical judgment. The soaring costs and tension are likely to continue as other expensive drugs reach the market.

“Now we have a wonder drug for hepatitis C; in fact, we have several, but as soon as the drugs appeared they’ve been snatched from our grasp,” Brian R. Edlin, associate professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, said. “We could literally end the hepatitis C epidemic if we put these tools to use.”

———-endquote———

No attempt at all, in the article, to analyze WHY those prices are so high.

9. April 2015 at 06:29

The economic Malthusians have been wrong for 200 years, and they’ll probably continue to be wrong for another 200. Peak oil, peak water, peak food….. We will all die any minute now.

The Malthusians ignore the economics which includes substitutes and price signals generating innovation and/or reduced consumption. The Agriculture is terribly inefficient due to all of the intervention which screws up correct price signals. Subsidies, ethanol, price floors, mandates and now patented crops all screw up the “market.”

The solution to the water problem is to allow supply and demand to actually work. The price in Calf would naturally go up which would spur probably some innovative investments into desalinization plants increasing the supply. This is all basic micro.

9. April 2015 at 06:56

Good luck explaining that. Malthusianism is a core value on the left.

9. April 2015 at 09:20

Hitchens (perhaps quoting Orwell) once said that 90% of the time the job of the public intellectual is to say “that’s not that simple”, but there is a vital 10% where you need to say “it’s actually simpler than you make it out”.

The California water “shortage” is one of these issues: it’s a completely trivial issue.

9. April 2015 at 09:26

@Sumner – I’m batting 1000? Then so is distinguished Mercatus scholar and gentleman Dr. Alex Taberrok, in today’s post at Marginal Revolution. Great minds think alike: Moral Suasion vs. Price Incentives for Conservation – See more at: http://marginalrevolution.com/#sthash.u89GvQ36.dpuf (“Moral suasion worked but not nearly as well as economic incentives (in the figure, lower use is better).”) Note where the control is.

9. April 2015 at 10:04

‘…there is a vital 10% where you need to say “it’s actually simpler than you make it out”.’

I’d reverse your percentages, Luis. The most common problem with journalists is overlooking the obvious; supply, demand, price. I’m sure I’ve read hundreds, if not thousands, of news articles about traffic congestion without ever seeing a hint that it could be made to go away immediately by pricing the use of roads during rush hour.

Same for unemployment, education, ‘discrimination’….

9. April 2015 at 15:10

@Ray Lopez: “I’m batting 1000? Then so is … Alex Taberrok”

LOL. You can’t even understand your own links! I’d love to hear what YOU think the conclusion is from Tabarrok’s [not “Taberrok”] post. In what way do you think it supports anything that you’ve ever said?

9. April 2015 at 17:01

Patrick: “No attempt at all, in the article, to analyze WHY those prices are so high”

As it will one day say on prof. Sumner’s tombstone on days when the grass needs to be cut, “Never reason from a price”.

9. April 2015 at 21:35

@DonG – this is not a distance learning portal. Read AlexT’s post, Mr. Grammerican, and see how ‘moral suasion’ beats doing nothing, though it’s worse than the price allocating mechanism. Big words I know. NY Times article = moral suasion.

10. April 2015 at 06:23

I must say I am a big fan of Ray Lopez posts (sorry if this offends some people). I have had so much joy since reading his posts. I was ROFL laughing as he continues his posting. It’s the combination of incomprehension, self-unawareness, bellicose and grandiose prose that is just pure genius. Ray (or whoever created his persona) is pure comedic genius. We haven’t seen such talent since Cervantes.

10. April 2015 at 07:15

LC, Agreed. I couldn’t even write such clownish posts if I tried. It’s a rare skill, and Ray does it better than anyone.

10. April 2015 at 08:46

Dr. Summers,

You analysis is surprisingly naïve. You do not understand the technical, legal, or political issues involved.

You wrote: “Roughly 80% of the water is used by farmers, who squander vast quantities of water each year by employing extremely wasteful irrigation techniques in order to export crops like almonds. And that occurs because the price at which water is sold to farmers is absurdly low.”

First, many, perhaps most, farmers do not “buy” water. They own water rights and produce their own water, either through surface water diversions or by pumping groundwater. These waters is very cheap because it costs very little to produce. Historically a farmer could drill a well and bring water to the surface for 50 to 100 United States Dollars (USD) per 1,000 cubic meters. Diverted surface water flows are not dis-similarly priced. That is not “absurdly low”, it is the cost of production.

You wrote that the irrigation techniques used are “wasteful”, but compared to what? What are the not wasteful irrigation techniques that could be used that are not? Could they be deployed overnight?

California of course has a number of enormous water conveyance systems, the California State Water Project, the Central Valley Project, the Colorado River Aqueduct, to name the largest and most obvious. Many farmers do buy water from these operations at considerably higher costs than locally produced water but at considerably lower costs than urban users. However the price paid for the water is also not “absurdly low”, it is the price of production. Urban users pay more because most agricultural users can obtain their water with minimal pumping while coastal urban users, such as Los Angeles, have to be pumped over and through many miles of mountains.

The same water delivery systems that bring water to agriculture in California also bring the water to urban users. It is also a major source of electricity in California. So it is not as if the urban users could have gotten the water infrastructure and political support to get their water without agricultural support.

Second, it must be noted that agriculture is not a monolith in California, there are different water users with different water rights. An examination of the Central Valley will reveal that more than a few farms, including the “water hogs” like almonds, have in fact stopped using water, altogether, There are dead orchards in many parts of the Central Valley which located immediately adjacent to green vibrant fields. The former had inferior or junior water rights to the latter. That is how water gets allocated, it is an all or nothing proposition. So it is not as if “Agriculture” is not cutting back, it is that the agricultural enterprises with superior water rights are not cutting back.

Third, the State of California cannot simply re-write over 200 years of water rights with wave of its hand. There are parties with water rights granted by the King Spain in the 1700s and when California was acquired by the United States, these “Pueblo Rights” were recognized by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Many more water rights go back to the mid-1800’s. It is wildly unrealistic to imagine that this old and complex system of water rights can be completely re-written overnight.

Fourth, agriculture in California is extremely important to the economy. Exports alone were worth 21 billion USD in 2013. While this is small compared to the gross domestic product of California as whole (2 trillion USD), agriculture is the entire economy of many counties. While California is one of the wealthiest states in the United States, the counties of the Central Valley are rather poor. Yolo County (population 198,889) has a per capita income of 28,631 USD and Yuba County (population 71,817) 20,046 USD. For the poorest parts of California, the drought has already been devastating economically, further cut backs on water usage would be equally so.

Finally, from a political perspective, it is entirely unrealistic to imagine that the state government in California would take any course that would be exceeding detrimental to the economy of large parts of California which are well represented in the legislature.

What you suggest would incredibly complex from a technical perspective, a legal perspective, an economic perspective, and from a political perspective.

Perhaps there are changes that can be made to imagine that they can be done all at once is simply not realistic.

10. April 2015 at 08:54

David, Next time I suggest you read my entire post before commenting.

I said the politics of reform are “complex” and you call me naive for not understanding that the politics of reform are complex.

Well done.

And as for the claim that price should reflect the average “cost of production,” may I suggest that you take an EC101 class. That’s truly naive.

10. April 2015 at 10:53

Dr. Summers,

If I own my own well, why would the price of my water be anything other than my own costs? Your entire argument is based upon the premise that agricultural water is “absurdly low” but you provide no evidence for this assertion. Why is it low, compared to what? If the price of agricultural water is not “absurdly low”, your entire blog makes no sense.

Further, you wrote:”The problem is simple to explain and (in a technical sense) simple to solve.”

As I believe that I demonstrated, it is not simple in any technical sense. It is not just the politics that complex, it is the legal, economic, and technical issues that complex.

10. April 2015 at 11:15

@David: Does your well draw water from a shared underground aquifer? Then there are unclear property rights, and the water market suffers from a Tragedy of the Commons. Is a fixed price (perhaps based on “cost of production”) baked into diverting surface water? Then the free market price system is unable to allocate water to its most efficient economic use.

If California had a free market in water, what you would find is that the almond growers in the center of the state, rather than using huge amounts of water in order to grow almonds, would change businesses from being “farmers” to being “water suppliers”, and would close their farms and sell their water property rights to thirsty L.A. consumers.

What price are local water utilities allowed to charge for water? In L.A. or San Francisco, if there “isn’t enough water”, then why isn’t the retail price for an ordinary consumer doubling or tripling? Why does the retail price for ordinary consumer water remain the same, but attempts are made to use moral suasion in order to stop regular people from buying as much as they want, at the prices offered? (Yes, there’s an aspect that “water is necessary for life!”, but there are far simpler and more direct ways of solving that problem.)

The politics & legal situation is complex, yes. (And that’s why nothing is fixed.) But the economics is trivial. And the engineering issues are easily solvable. This is not a “hard” economic problem.

10. April 2015 at 11:18

@Ray Lopez: “see how ‘moral suasion’ beats doing nothing”

Was someone arguing that “doing nothing” is more effective than moral suasion? Who, specifically, do you think was making such an argument?

What I saw was the observation that it’s stupid to choose a second-best alternative, when there’s a first-best alternative right in front of you. But there you go, advocating for 2nd best.

10. April 2015 at 11:58

Hello Don Geddis,

I must disagree with your assessment.

1) Almond farming is not necessarily water intensive. Almonds originated in the dry regions of Eurasia and were cultivated for centuries without irrigation on hillsides. However about 100 years ago California growers discovered that if they planted their trees in lowlands and irrigated, production could double or triple. Currently, many almond growing are using drip irrigation[1] which does not use nearly as much water as traditional flood irrigation.

2) You are assuming that there are conveyances to move water from any point in California to any other point. This is not the case. Much groundwater, and even a lot of surface water is “landlocked”, there are no conveyances available. Further, the transport of water long distances is extremely expensive, water is very dense and it requires considerable energy to move it to coastal urban centers such as Los Angeles or San Francisco. Wide and tall mountain ranges separate the water from the cities.

3) Some farmers can fallow their land and sell water to urban markets. The rice farmers of the San Francisco Bay Delta have done this. They can skip a year and plant the following year without an difficulty. However many farmers cannot do this. Grape vines and almond trees die without enough water. It takes several years to develop a profitable vineyards and orchards and all of that is lost with just one dry season without irrigation.

4) Here however is the real issue, what happens to the local economy when farmers fallow their fields and sell their water. There are large swaths of California the are entirely dependent upon agriculture. The entire population depends upon the wages and spending of farmers. Without agriculture, these regions would simply dry up and blow away.

5) The reason that urban water prices are so much higher is two fold, one is it costs much more to move water to large coastal cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles. The other is that it requires a great deal more treatment. Agricultural water can generally simply be applied as is. Potable water must be treated and surface water especially so. Large Surface Water Treatment Plants cost millions of dollars to build and are expensive to operate.

[1] http://californiaagriculture.ucanr.edu/landingpage.cfm?article=ca.v053n02p39&fulltext=yes

10. April 2015 at 15:20

Sumner wrote:

“And as for the claim that price should reflect the average “cost of production,” may I suggest that you take an EC101 class. That’s truly naive.”

What is naive is believing that what Econ 101 teaches about the determinants of prices, is how business people actually set their prices.

It is in fact the case that there is a large class of goods the prices of which are indeed determined by costs of production. This class of goods are manufactured goods. I don’t want to get into a lengthy discussion on this, because it would take a larger post than even I often submit here. I will just say that one of the more revealing historical facts of pricing that aid in our understanding of human actions, is the empirical tendency of selling prices in a competitive market to fall when the sellers succeed in cutting costs, especially labor costs. It is one important reason why prices of Chinese goods are lower than domestically produced goods, even after taking into account such things as trade barriers, foreign exchange, and other rather easily controllable variables.

Prices of manufactured goods tend to fall when labor costs fall because prices of manufactured goods tend to gravitate towards costs of production (plus a competitive rate of profit).

This is not taught in “Econ 101” because cost based pricing was one (among many) of the classical economics principles that was abandoned (unjustifiably, IMO) when the labor theory of value was abandoned. The abanondment of the LTV was perceived and treated as an abandoning of classical economics as a whole. Throwing the baby out with the bath water, so to speak.

The reason this occurred is because by the time of the 1920s and 1930s, economists the world over had to contend with the rising tide of the “New Economics”, I.e. Keynesianism, which held that rising nominal wages was a good thing, period, even during depressions when demand falls and where market clearing wage rates would be lower, not higher.

Economists up until that time knew and taught that falling wage rates cures depressions, but that was a very uncomfortable position for them to be in. Once Keynes arrived on the scene, and as his popularity grew, more and more economists could join in the calls for higher wage rates, and they didn’t have to appear as curmudgeon Scrooges to the rest of society.

One of the big costs of the Keynesian revolution was an abandonment of not only the classical doctrine of falling wage rates curing depressions, but most of classical economics.

The doctrine of “fair pricing” where marginal costs equals marginal revenues arose out of the anti-capitalism tide that Keynesianism very much helped. Anti-trust legislation was the new political “war on…” greedy cash hoarding capitalists.

Econ 101 does NOT constitute a sufficient body of knowledge that would enable us to understand real world pricing.

If you want to know how prices are set, it is best to find out how market makers think and behave, and study the criteria they use. Ignore cranky clueless economists who have a political agenda to push.

10. April 2015 at 16:24

Notice how Scott slips in the word “average” when referring to the costs of production in David’s original post, as a means of suggesting economic illiteracy? So blatant. Not just dishonest, but incompetent. What a fraud.

10. April 2015 at 16:54

David, If it costs so much more to provide water to the cities then why do you want to ban farmers from doing so?

And your claim that agriculture in the Central Valley would vanish if they went from using 80% of California’s water to 75% (through more efficient methods like drip irrigation) is just laughable.

Beefcake, Surely you don’t think he was claiming that water is priced on a marginal cost basis? Even I don’t think he’s that naive.

In any case, if water were priced at MC then there couldn’t possibly be any water shortage, could there?

10. April 2015 at 16:55

David, So you are claiming that 100% of agricultural water use comes from well water? I don’t believe that.

10. April 2015 at 21:48

A hard perennial; my own State of Victoria had massive immigration (population increased by 30% in a time when no new dams were built), no new capacity and prices ludicrously low, and so had water shortages “because” of the recent drought.

10. April 2015 at 21:49

Should be “hardy perennial”

10. April 2015 at 22:31

David de los Ãngeles BuendÃa’s nuanced response is ignored by Sumner, who wishes away all the problems David raises. If only MC = MR then magically all things would be solved (typical of free marketeers). But it ignores history, which governs actual human relations. Most people do not care about economic efficiency; due process and historical precedent is more important. What is being played out in SoCal today happened many times before, for example in the early 1990s, and nothing much changes. A good starting point for Sumner, a film buff, is Chinatown (1974 film).

11. April 2015 at 05:14

Agriculture does of course confront marginal costs:

http://www.wsj.com/articles/californias-farm-water-scapegoat-1428706579

Surprising that Scott does not identify environmentalism as playing a role in all of this. He also has not acknowledged the point that urban users should pay more for water because of transport and treatment costs. Easier, I suppose, to demagogue about rural vs urban narratives (on this, witness Benjamin Cole’s seething hatred, typical of “liberals”).

11. April 2015 at 06:20

Ray, You said:

“If only MC = MR then magically all things would be solved (typical of free marketeers). But it ignores history, which governs actual human relations. Most people do not care about economic efficiency;”

Yes, that’s right Ray, “economic efficiency” implies MC = MR. Can you be any dumber?

I’ve seen Chinatown several times, but unlike you I don’t get my economic analysis from Hollywood movies.

PS. Efficiency implies MC = P. It’s all in EC101.

Beefcake, I’m not asking farmers to “confront” MC, I’m asking them to pay MC. If California water is priced at MC then there is no shortage. Is that your claim?

As for the difference in price merely reflecting transport costs, that just insults our intelligence.

Again, why not let farmers sell as much water as they wish to the cities?

People go to rather absurd lengths to defend the NYT.

11. April 2015 at 06:35

Sumner wrote:

“Yes, that’s right Ray, “economic efficiency” implies MC = MR. Can you be any dumber?”

“PS. Efficiency implies MC = P. It’s all in EC101.”

Good thing this is a blog not a classroom where you can actually adversely affect people’s lives by making it a requirement to write (and possibly believe) such confusion.

In a “perfect” market, which is what this “efficiency” refers to, the correct relation is:

“If the firm is a perfect competitor, so that it is so small in the market that its quantity produced and sold has no effect on the price, then the price elasticity of demand is negative infinity, and marginal revenue simply equals the (market-determined) price.”

http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marginal_revenue

So if perfect market competition entails MC = P, then because MR = P, it follows that MC = MR.

11. April 2015 at 07:12

@David

If there was a free market price for water, and you costs are very low, you would probably want to sell some of that water for a profit. I think that Prof Sumner by using the term EC101 he was referring to a well know problem in micro economics which is the upstream-downstream transfer price. As a water producer and water consumer, this is a vertically integrated operation, the downstream price charged by the upstream division should be the market price, otherwise there is a loss um society welfare. This is one exemple of micro economics that is very well known…

11. April 2015 at 08:09

@MF, Robazzi, thanks to MF for that amplification, and Robazzi you should be aware that water utilities are a classic example of ‘natural monopolies’ so indeed P != MC (cannot equal) and in fact average costs in a natural monopoly, which fall with quantity produced, is more accurate (and I think utility commissions use avg cost in their analysis).

Also this: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Burry (Burry made $100M for himself by foreseeing the collapse in mortgaged-backed securities before 2008. Also this: “as of 2012 he was managing his own investments, which included almond farms in California, “a fancy way to essentially invest long-term in water.” Michael Lewis said, “they require a lot of water to grow and he’s got a very complicated argument about why these almond farms are a good idea, so I trust him.”)

11. April 2015 at 08:10

Dr. Sumner,

You wrote:”If it costs so much more to provide water to the cities then why do you want to ban farmers from doing so?”

I never wrote that I wanted to ban farmers from selling water to urban users. I merely noted that it is simply impractical in the majority of cases and that there would be severe economic consequences to the long term fallowing of agricultural lands.

You wrote:”…your claim that agriculture in the Central Valley would vanish if they went from using 80% of California’s water to 75% (through more efficient methods like drip irrigation) is just laughable.”

I did not write that. I wrote that if land was *fallowed* there would be serious economic consequences. I should note there are already severe economic consequences from the drought so far. As I noted, there are plenty of fallow lands and dead orchards. This not hypothetical, it is already happening. No on is laughing.

You wrote: “So you are claiming that 100% of agricultural water use comes from well water? I don’t believe that.”

I did not write that. In my first paragraph I wrote:”First, many, perhaps most, farmers do not ‘buy’ water. They own water rights and produce their own water, either through *surface water diversions* or by pumping groundwater.”

11. April 2015 at 08:12

Greg Mankiw recommends a post by Noah Smith:

http://gregmankiw.blogspot.com/2015/04/the-sticky-price-victory.html

11. April 2015 at 08:24

@Scott

So, pointing out the flaws in your argument implies defending the NYT? Got it. You know, such defensiveness and misdirection suggests you’re not that confident in your arguments yourself. And who said anything about not letting farmers sell water to the cities? Who’s going to pay for transport and making it potable?

BTW did you read the WSJ link? I trust you’ll drop the whole “agriculture uses 80% of Cali’s water” line?

11. April 2015 at 08:45

Dr. Sumner and other commenters,

I believe that one element of this discussion that may not be clear is the drought in the west (it is not confined to California) is that there have already been a great deal less water being used in agriculture, not through reduced allocations or water right but because wells have physically run dry, in many locations there is no water at all. Orchards, including almond orchards, have died for want of water. There are towns without drinking water which must now bring in water via trucks. There have already been severe economic consequences. Further curtailing farmers access to water will worsen this situation.

Now, with that said, that does not mean that there should not be limitations on water use in agriculture as other water users must. Farmers have transitioned to more efficient irrigation techniques. As noted above, almond growers have been using drip irrigation. It is not a simple situation.

http://www.sfgate.com/science/article/California-drought-How-water-crisis-is-worse-for-5341382.php

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=103950335

http://www.wsj.com/articles/central-california-farmers-anticipate-no-federal-water-amid-drought-1425060533

11. April 2015 at 09:38

Ray, Yes, the MC of producing water is declining with added output. That’s why California has a water shortage. Idiot.

David, So you didn’t say any of the things you seemed to be saying. In which case you have no complaints with my post. Fine.

Everyone, Is there anyone here who’s taken EC101? If you price water at MC there is no water shortage. Period, end of story. This is not rocket science.

11. April 2015 at 10:14

Straying away from the almond farms for a moment…

“QE and the bank lending channel in the United Kingdom”

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/Documents/workingpapers/2014/wp511.pdf

Hot potato!

11. April 2015 at 11:25

@Ray

Well, I don’t know of natural monopolies, but if there is a shortage and people still believe ‘water is cheap’ I see a dysfunctional market, free market and good property rights set will help, and the price of water will probably rise. In this subject i sympathize with the Austrians: monopolies are a creation of society, and probably exist because there are no property rights or badly designed property rights.

11. April 2015 at 18:12

David, I’m really struggling to see your point, it just seems like a bunch of non sequiturs regarding the changing dynamics of agriculture the drought has caused (well duh), in what way at all does it challenge the point about water being sub-optimally priced in California?

11. April 2015 at 18:43

Hello Britonomist and Dr. Sumner,

It was asserted in this piece that the fundamental problem in the drought afflicting California and other western states is that the price of water is too low, “absurdly low” in fact. My point is that this is incorrect, the problem is not the price of water. The problem is that there is no water in many parts of California and too little water in other parts. The problem is that it has not rained or snowed enough and changing the price of water will not make it appear where it is not.

I should note that the New York Times is equally wrong, it is not a problem of too many people. California has had crippling droughts in the past when the population was much smaller population (and almonds were not grown).

This is not to say that there are not plenty of problems in regards in water in California, there legal, political, and technical problems. However they are not simple and changing the price of water will solve them.

11. April 2015 at 19:19

It would be interesting to take a poll of people who understand that X shortages are caused by mis-pricing X (water, parking spaces, stable CO2 content of the atmosphere, urban residential property) to find out which party they vote for.

11. April 2015 at 19:47

“However they are not simple and changing the price of water will solve them.”

You didn’t provide a single reason as to why changing the price wouldn’t help. Water needs to be rationed in California right now. Water is not being rationally or well rationed in California right now. From these axioms it seems pretty self evident that raising the price of water would ensure it is ‘rationed’ better, unless you just completely disregard economics/substitution effects etc… It doesn’t matter if the situation is complex, changing the price of a commodity can cause /highly complex and dynamic changes to the market/ if you decide to analyze everything in a disaggregated context, this is econ 101.

11. April 2015 at 19:52

@ssumner (being sarcastic, I hope): “Ray, Yes, the MC of producing water is declining with added output. That’s why California has a water shortage.” – no, you confuse apples and oranges (again). You were pointing out MR = P = MC in a perfect competition market (which we DON’T have) while I was pointing out the equal truth that MC declines to zero in a natural monopoly, like a water utility (which of course we also don’t have). Do keep up.

11. April 2015 at 22:04

Hello Britonomist,

1) What is the price of a commodity that does not exist?

Above in a previous posting I linked an article from the Wall Street Journal indicating that the Central Valley Project (CVP), a conveyance system operated by the Federal Bureau of Reclamation, would deliver NO WATER (0 cubic meters) to any of it’s customers. The reason that the CVP would do this is that is that the rivers and lakes that feed the CVP are dry, they have no water. The CVP could raise the price of the water as much as it likes, it will still sell no water, because there is none.

2) The Water Market is Imperfect

It is easy to imagine a perfect, frictionless water market where every supplier of water can sell any excess water to any potential buyer but this is not the case. There may well a water rights holder on the Klamath River in Happy Camp that would be more than content to sell his or her excess water to Paramount Farms in North Hills 1,000 kilometers to the south at a healthy mark-up in price. However there is no physical means for this to occur, one may just as well try to buy water from providers in Alaska or Maine. Transporting water is very expensive when it can be done at all. It simply not possible to move water from any point in California to any point California at any price.

3) Agri-Business is not Stupid

Agriculture in California is dominated by very large corporations with very significant long term investments in fruits like almonds and which have very extensive financial resources. They did indeed make offers to other holders of water rights to buy water at elevated prices in the past to keep their trees, and capital, alive. However if one reads the linked pieces above to National Public Radio and the San Francisco Gate it would be possible to see that vast orchards of almonds were torn up and turned into wood chips because the trees died for want of water, *last year*. Considerable losses were tallied when these extensive groves died. One may rest assured that these gigantic corporations did all that was physically and financially possible to secure water for their capital and those trees only died because no water was obtainable at any price.

If there were a simple solution, it would have been found.

12. April 2015 at 06:26

” The CVP could raise the price of the water as much as it likes, it will still sell no water, because there is none.”

Irrelevant, this is not about The CVP.

“2) The Water Market is Imperfect

It is easy to imagine a perfect, frictionless water market”

Irrelevant, no assumption was made. Honestly, read some modern contract economics some time. Read about transactions costs.

” However there is no physical means for this to occur”

Remember when people said it was either not possible, or uneconomical to tap into large shale oil reserves found? Then the price of oil went up, and suddenly new technology was brought in, and things that seemed absurd and impractical at one time suddenly became a booming industry. I cannot stress how powerful a change in price can be for an industry. It doesn’t matter if the market faces considerable frictions or not. Also there are many more options than the ones you are presenting here, nobody is saying that raising the price must result in one specific transport of water from one specific area to another specific area – I’ve read of all kinds of possibilities to get more water into California. Some include new irrigation techniques, some involve transporting water, some involve desalination etc… The only barrier for each one I’ve heard is the cost, making potential ventures unprofitable, but if they could get more of a return on the water they sell…

“all that was physically and financially possible”

A) To save their own farms, but this is a strawman because nobody is saying all farmland should be saved in the first place.

B) Nobody is necessarily looking to farmers to solve the water shortage problem themselves, other than by perhaps using less water themselves (and yes, this may mean some farmers go out of business).

C) Companies that may be in the business of delivering water or finding new water sources (NOT FARMERS) can only do so much at current prices before bankrupting themselves

D) Did you even read the NPR piece, because farmers seemed to have some good ideas about solutions there, they seemed to be the opinion that the problem was political, not natural. Politics involving the Delta estuary. Or a lack of initiative in developing a new Canal to lead water around the Delta estuary, hmm I wonder what might give the water industry more an initiative to develop something like this, hmm?

“If there were a simple solution, it would have been found.”

Raising a price would certainly help businesses, entrepreneurs or even local government find a solution. That’s the entire point. Nobody said the solution they might find will be necessarily simple. Nobody said that all farmers will be safe and not go out of business.

12. April 2015 at 06:50

Even if we ignore farmers for a second, consider this quote:

“Urban areas use about 20 percent of the state’s developed water supply, much of which is delivered from reservoirs hundreds of miles away at great ecological and energy cost. Improved efficiency, stormwater capture, and greater water reuse can together save a total of 5.2 to 7.1 million acre-feet of water per year, enough water to supply all of urban Southern California and have water remaining to help restore ecosystems and recharge aquifers. These approaches also cut energy use, boost local water reliability, and improve water quality in coastal regions.”

http://pacinst.org/publication/ca-water-supply-solutions/

Oh, I wonder what might provide incentives for people to conserve and recycle their water? Might they just do this out of the goodness of their heart? Or hmm, maybe some kind of financial incentive might help? :O

12. April 2015 at 07:28

Thanks Jim, I’ll do a post.

David, If there is too little water you need a higher price to allocate the water, that’s EC101. The fact that there is a drought is completely irrelevant.

The three points in your second comment have no bearing on this discussion. It’s not clear why you even mention them. I see Britonomist has a better reply.

Ray, You said:

“You were pointing out MR = P = MC in a perfect competition market”

No I did not. Can’t you understand anything?

But it’s good to know the MC of producing water declines to zero, that will cheer up the Californians.

12. April 2015 at 09:02

Dr. Sumner and Brionomist,

Both of you seem to assume that the price of water is some how fixed. This is not true. There is indeed an open market for water, where conveyance is possible. In a previous drought, about 25 years ago, the rice farmers of the SFBD fallowed their rice paddies and sold their water. Their mark up as a factor of ten. They sold water that cost them, at that time less than 100 United States Dollars (USD) per 1,000 cubic meters and got for it for 1,000 USD. There have been all sorts similar transactions over the years under various market conditions. So you are proposing a solution that already exists.

Today, the problem is not a lack of ability for the purveyors of water to sell water at water ever price that the market will bear but the lack of water. Farmers cannot sell water that they do not have. Urban users cannot buy water that does not exist. Price is irrelevant when there is no supply.

12. April 2015 at 09:13

“Both of you seem to assume that the price of water is some how fixed. ”

I assume not that it’s fixed, but that in many cases it is either too cheap or with incoherently defined property rights. Perhaps if it was fixed though, things would be easier. The fact is, many agencies are constantly highlighting how wastefully water is being used in California, ensuring that water is not under-priced would certainly help to reduce waste, and may even encourage innovations in the industry.

” Urban users cannot buy water that does not exist.”

Urban users are not facing a water shortage yet, did you even read my second post? Not only are urban users still able to get water cheaply, they are still being wasteful with it (even after years of efficiency measures), if it was less cheap they’d perhaps be more inclined to use it more efficiently and use methods outlined by for instance the pacific institute. The problem (for urban users) currently is not that there is a sudden major water shortage, but that water is running out fast such that major shortages could occur unless behaviour changes – a great way to change behaviour is through better pricing. Here in Britain they’ve recently installed a water meter at my parents house, and I can say that this has encouraged them to greatly reduce their water usage, and it enabled them to identify a major leak that probably would not have been noticed before were it not for the unusually high bills they were receiving.

12. April 2015 at 09:20

None of your criticisms are even coherent. If we’ve hit a hard supply constraint that cannot possibly be increased, that doesn’t affect the fact that pricing is how scarce resources is allocated, again as Scott says this is Econ 101. If California cannot get more supply, then the current supply of water must be more efficiently allocated – wasteful usage suggests it is being under-priced, regardless of whether they can get more supply or not, what is wrong with this analysis?

But the other problem is that it’s a myth, at least for urban consumers, that there is no more supply. Supply is just becoming more expensive, major urban areas can easily satisfy their future water demand if they decide to do major investments in water desalinization plants or other projects, the problem is that these are very expensive and require a lot of energy. This is where pricing again comes into play, perhaps if water was priced higher in urban areas, it would reduce waste and remove any need for these projects in the first place, but if not, the increased income from the pricing would go towards paying for the plants. Econ 101.

12. April 2015 at 10:01

I think this analysis from Michael Hiltzik ( http://www.latimes.com/business/hiltzik/la-fi-hiltzik-20150412-column.html#page=1 ) is good, notice that he also holds that “The only lasting solutions include creating a better-functioning water market with transparent pricing and transfers, so that water supplies end up where they’re most needed and most economically useful.”

12. April 2015 at 10:10

And here’s the New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2015/04/07/can-farms-survive-without-drying-up-california-13/california-needs-better-water-management-and-pricing-policies

“We can and must do better. We need a statewide system to track water use. We must adopt water prices and pricing structures that effectively communicate the value of water. We must provide financial incentives to modernize water delivery systems and improve on-farm water management practices.”

Seems almost every analysis I read includes a proposition like this, from people who are clearly anything but ‘naive’ on the issue.

12. April 2015 at 10:25

Here’s Forbes:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/beltway/2015/04/07/one-solution-to-californias-drought-tax-water/

“y contrast, a tax would be relatively easy to administer. If a B-list owner of a Beverly Hills mini-mansion really felt the need keep his green lawn, he could do so. But he’d have to pay a tax.

If a farmer wanted to grow water-intensive crops such as almonds or rice (in a state where it has barely rained in 3 years), he still could. But his price would include the tax.

If more expensive water makes that farmer no longer cost-competitive, he’d have to invest in new water-saving technology or do something else with his land. But it would be his choice. He wouldn’t be barred from water-intensive farming. He’d just have to pay the real cost of using a scarce resource.

The state could use some of the revenue from the new tax to help fund conservation efforts, desalinization plants, or the like. A new report by the Public Policy Institute of California finds that local revenues account for 84 percent of water spending in California (the state contributes just 12 percent), and that while urban systems are in good financial health, other districts””including those in rural areas””face severe shortfalls. Those localities are often the most resistant to tax hikes but also the biggest per capita users of water.

Revenues from a statewide tax could be used to address some of those challenges. However, if lawmakers preferred, the state could rebate some of the tax on a per capita basis, or even according to an income-based formula to mitigate the cost of the levy for poor households. The idea is that revenues from a water fee could help alleviate local water issues, or might be offset by other tax cuts. But a tax on water could help change behavior””a necessary step in a state that simply does not have enough.”

12. April 2015 at 10:44

Here’s vox on inefficiencies getting in the way of water trading:

“Plus these farmers can’t easily sell their water rights to other people in California who might find better use for it “” there are complex rules ( http://www.hamiltonproject.org/files/downloads_and_links/market_mitigate_water_shortage_in_west_paper_glennon_final.pdf ) standing in the way of water trading. So farmers use cheap water to grow alfalfa, even though it’s sort of a waste.”

And on pricing:

“Economists also point out that the price of water varies a lot from city to city ( http://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/the_path_to_water_innovation/ ), with little relationship to scarcity. And wasteful water use is likely to continue so long as water is underpriced.”

12. April 2015 at 10:47

Finally, here’s ‘The Hamilton Project’:

http://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/the_path_to_water_innovation/

“Solutions to the country’s growing water challenges lie, in part, with the development and adoption of new innovative technologies. Yet, in comparison to the electric power sector, investment in water innovation is extremely low. Indeed, investment by the savviest promoters of innovation””such as venture capital and corporate research and development””are strikingly low in the United States and globally when compared with other major sectors of the economy. This low investment helps explain low levels of innovative output, as measured by patent filings and other data. Adoption and dissemination of new innovations are also slow.

The primary barriers to innovation are related to the way that the many layers of governmental agencies and water entities manage the nation’s water sector. Among the main management and policy barriers are (1) unrealistically low water pricing rates; (2) unnecessary regulatory restrictions; (3) the absence of regulatory incentives; (4) lack of access to capital and funding; (5) concerns about public health and possible risks associated with adopting new technologies with limited records; (6) the geographical and functional fragmentation of the industry; and (7) the long life expectancy, size, and complexity of most water systems. Although the last three factors are inherent to the water sector and hard to change, substantial policy reforms are feasible that could alter pricing, regulation, and finance in the water sector””all in ways that would encourage innovation. ”

Who would have thought unrealistically low water pricing rates could be stifling innovation in the sector, compared to electricity?

12. April 2015 at 10:54

Forgot to link to the vox article: http://www.vox.com/2015/4/10/8379221/california-drought-water-crisis

13. April 2015 at 06:59

Farmers planting annual crops like rice and vegetables will gladly sell their water. I’m sure this will spur farmers across the nation to grow more of the displaced crops and products (milk) and the impact will be marginal. In fact, given our farm subsidies, this will actually save the federal government money….

http://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2015/03/17/drought-some-northern-california-farmers-not-planting-sell-water-rights-los-angeles/

13. April 2015 at 07:26

David, No one is advocating putting a price on the water that does not exist, we are advocating pricing the water that does exist at MC, to eliminate the water shortage.

Britonomist, Thanks for being a voice of reason here.

13. April 2015 at 08:20

Hello Britonomist,

Dr. Sumner’s piece is a critique of the response of the government of the State of California to the current drought. In his piece he says that while the politics may be complex, “The problem is simple to explain and (in a technical sense) simple to solve” and that the problem is “the price at which water is sold to farmers is absurdly low”. My response has been that this is not the problem and that the solution must involve changes to law, water rights, and technology which will be complex.

Everything that you posted in the last 24 hours supports by position that there is no “simple solution”, it is complicated and complex involving more than just changing prices. Indeed, as the Hamilton Project notes one of the most important problems are “(6) the geographical and functional fragmentation of the industry”. It is physically difficult, not impossible as it does happen, to move water between parties.

What none of your references show is what the price of water is or that it is low, absurdly or otherwise. Nowhere do you, Dr. Sumner, the Hamilton Project, or any other referenced piece mention an actual prices. If an alfalfa farmers owns his or her own waters rights and wells, the price of 50 United States Dollars (USD) per 1,000 cubic meters (TCM), why is that “low”? What is it low compared to? If an urban water utility has a similar well, it can bring water to the surface at the same cost. The alfalfa farmer only sells water to his or her own farm but it still costs just as much as the urban water utility which sells potable water to domestic customers. The price of the groundwater, were it sold for the same purposes, would not be different.

So what is still lacking is any demonstration that the price of water is “absurdly low”. Agricultural groundwater does not cost more or less to produce than urban groundwater. Also, groundwater is rarely transported very far. Large urban water users, San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, when they import water from distant parts of California, import surface water, not ground water. When farmers sell their water to urban users, which some can do and have done, they sell surface water, not groundwater.

So much of this discussion is apples and oranges. You and Dr. Sumner and the linked authors are combining “cheap groundwater” with imported surface water.

Surface water is where there are wide differences in price. The price paid by an farmers in the Central Valley for imported surface, mainly through the Central Valley Project (CVP)[1], the largest seller of agricultural water in the state, is quite a bit cheaper than similar water sold to urban users. However this is because there are significantly different costs.

Water delivered to farmers by the CVP costs relatively little to move about the Central Valley. The Central Valley is rather flat and water can be made to flow about with only a little bit of pumping, gravity moves most of it. This is not the case for cities like Los Angeles or San Diego or San Francisco. They must move water over 1,000 kilometers over and through several mountain ranges. To get to Los Angeles for example, the CVP moves the water south through canals and pumps and then transfers it to the State Water Project (SWP) which then lifts the water over the Tehachapi Mountians, through more aqueducts, then over the San Gabriel Mountains into reservoirs. Then the water must be treated to comply with the various Surface Water Treatment Rules to prevent the spread of waterborne pathogens which is very expensive and not required for agricultural water or groundwater. In southern California, imported surface water, treated in compliance with the various Surface Water Treatment Rules, costs around 2,000 USD/TCM, 40 times higher than agricultural groundwater in the Central Valley.

So of course groundwater used for agriculture costs much less than urban domestic water, it costs much less to produce.

Now, the above description is for non-drought conditions. What is occurring now is that there simply is no water in many places. Groundwater wells have dried up. Surface water suppliers have no more supply. Above I provided a link to the Wall Street Journal[2]indicating that the CVP would not be delivering any water at any price. One can no more ignore the CVP in discussing water in California than one can ignore discussing General Motors when discussing automobiles in the United States.

Just as closing note, the SWP has announced that it will only deliver 10 to 15% of the normal allocation of water to southern California[3] (south of the Tehachapi Mountains). Urban users are even more restricted from a quantity perspective than agricultural users.

[1] http://www.usbr.gov/projects/Project.jsp?proj_Name=Central+Valley+Project

[2] http://www.wsj.com/articles/central-california-farmers-anticipate-no-federal-water-amid-drought-1425060533

[3] http://www.water.ca.gov/swpao/docs/notices/15-01.pdf

13. April 2015 at 09:28

Dr. Sumner,

You indicate that you are not advocating putting a price on water that does not exist. This is the heart of your suggestion, that prices of water are too low for markets to efficiently allocate water among users. By implication, you are suggesting that the price of agricultural water should be higher. The problem in 2015 in California is that there is no water to be priced. As I noted above, twice, that the Central Valley Project, the largest provider of surface water to farmers by quite a bit, will be delivering zero water. As the Wall Street Journal notes: “California farmers face being cut off from federal water imports for the second straight year, in an unprecedented move likely to worsen crop losses in the nation’s biggest agricultural state.” Farmers cannot sell water that they do not have.

So the price of this water is not “absurdly low” and raising its price will not solve any problems.

13. April 2015 at 09:37

Hello Britonomist,

As an addendum, do you actually read the Vox piece that you linked?

“9) Water prices for farmers vary widely across the state

Water isn’t free. But what’s striking about California is that the price of water varies wildly from region to region “” and is often incredibly cheap for farmers.

Farmers in the Central Coast and South Coast pay roughly as much for water as residential users do. But farmers everywhere else only pay about one-sixth that amount [diagram]. Why the disparity? As the Legislative Analyst’s Office explains, the South Coast and Central Coast are served by the State Water Project, which has a higher cost of delivery. The other parts are served by federal water systems, which are largely paid off. Complex water contracts also affect the price.”

In other words, surface water for agriculture delivered to different parts of the state by different means different costs and different prices. This is the same point that I was making. “Absurdly low” water prices that some farmers see is because water costs absurdly less to produce for some farmers. Different prices reflect different costs.

I would also not that the concluding section is entitled “There’s no simple solution to California’s water woes”. I could not agree more.

13. April 2015 at 13:19

David, how long do you keep intending to attack a strawman. Nobody said the cost (& price) of water is uniform, I repeat, nobody said the cost (& price) of water is uniform. In economics, commodities can be inefficiently priced regardless of if there is a complex array of prices varied geographically, ranging from very high to very low, that doesn’t actually alter the analysis. You’re overly fixated on a simplifaction about pricing, the overall point, that every single one of my sources keeps stressing, is that the water markets at the moment are /clearly/ dysfunctional, and prices are often not conveying true information in incorporating externalities – this doesn’t imply the price will be uniform or always cheap.

A note on this:

“Groundwater wells have dried up.”

This doesn’t mean the supply isn’t there, what’s happened is the water table has lowered, which means farmers must create new wells that go deeper, which is expensive. But even if it’s expensive, it may not be as expensive as it should be, because of course you get a tragedy of the commons problem where (as EVERYONE IS STRESSING) groundwater is STILL being over-pumped BECAUSE THE PRICE DOES NOT REFLECT THE MAJOR EXTERNALITY OF GROUNDWATER DEPLETION. As all the sources keep highlighting, what’s ACTUALLY happening is that surface water is failing to meet demand, and therefore much more groundwater is being pumped to make up for the loss of supply of water to farmers. That some wells are going dry seems to be an irrelevant aside, this isn’t stopping groundwater from being pumped much more, enough to make many worried that this groundwater pumping is unsustainable in the long term. Perhaps if prices reflected this long term unsustainability externality (e.g. by properly taxing until the groundwater overdraft is reduced, as vox suggests, AND YES THIS WILL RESULT IN FALLOWED LAND NOBODY IS DISPUTING THIS) then the unsustainable trend will end. But if it has nothing to do with this, and groundwater isn’t being overpumped? Then you can’t blame Scott and me, because we’ve effectively been lied to by every single media outlet that has reported on this issue that consistently highlight the fact that groundwater has been overpumped by farmers – if this is not the case it’s ridiculous to attack us for it as we have no reasonable means of knowing otherwise.

I feel like you’re going out of your way to be contrarian and nitpicky.

13. April 2015 at 13:30

“Different prices reflect different costs.”

Have you actually studied economics before, ever? Have you heard about socialized costs which are unrelated to the production costs? Have you heard of externalities? The entire point is that the production cost of water may not be reflecting the true cost of this water to society, if it’s causing groundwater pumping to go into overdraft, which is unsustainable in the long term. Also again, you need to understand the difference between something that’s conceptually simple, and something which would be politically or legally simple to implement.

The concept is simple, it’s a classic case of tragedy of the commons, and the remedies to tragedy of the commons in theory and conceptually tend to be simple as well. This DOES NOT IMPLY it would be simple to implement politically or legally given the complex contractual problems.

13. April 2015 at 20:16

@David: “The problem in 2015 in California is that there is no water to be priced.”

You’ve said this numerous times. This is false. I live in California. I turn on the faucet in my home, right now, and water comes out. I will be billed for any water that I so consume.

I am not unique. I challenge you to find a single household, anywhere in California, where “there is no water” available, at any price (as you claim).

Given that EVERY community in California CONTINUES to sell additional water today, will you withdraw your silly claim that price changes have no potential to alter water consumption behavior?

14. April 2015 at 07:54

Hello Britonomist,

You wrote:””Groundwater wells have dried up.” This doesn’t mean the supply isn’t there, what’s happened is the water table has lowered, which means farmers must create new wells that go deeper, which is expensive. ”

No, I am afraid that that is exactly what it means. Pumpers have “lowering the bowls” for decades, pumping water from deeper and deeper in the aquifers. In the last four years, they have hit the bottom of the aquifer, there is simply no more water to be pumped at any cost or sold at any price. A similar situation exists surface water, providers of surface water, the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project have no more water to deliver. Raising prices will not produce more water.

This is the crux of the problem. The view advanced by you and Dr. Sumner is that if prices are some how raised, more water will appear. That was true was true in the past but it is not true now. There is as much water as there is and raising prices will note make any more water come out of the wells or into the canals.

This is what is so unprecedented about the current situation. This is why the state has taken such unprecedented actions.

14. April 2015 at 08:05

Hello Don Geddis,

You wrote:” I live in California. I turn on the faucet in my home, right now, and water comes out.”

1) You clearly do not live in the small communities of the Central Valley where people open their taps and nothing comes out[1]. There are people who now have to truck their water in. This problem is getting worse.