The Complacent Century

Looking backwards, it’s possible to see a number of turning points in the political zeitgeist. America moved toward (left wing) liberalism around 1964, then swung back toward (right wing) neoliberalism in the late 1970s, and then toward nationalism in recent years. And these were worldwide trends, with nationalism also on the rise in Europe, Russia, Turkey, India, China, Japan, and many other places.

Tyler Cowen pointed me to an article that suggests another turning point, which many people missed at the time. The new millennium ushered in an Age of Complacency:

The eminent political economist Ross Garnaut says the Great Australian Complacency, as he calls it, took hold of the political system from 2000. This locates it halfway through the Howard era.

How can he be so specific? Because, after John Howard and Peter Costello enacted their landmark reform of the tax system in 2000, they lost interest in further reform, on Garnaut’s reckoning.

And this marked the end of not only Howard-Costello reforms but an entire generation of near-continuous reform efforts that started in the years of the Hawke-Keating governments.

As is so often the case, people put far too much weight on specific local factors when thinking about these changes. Thus America’s move toward liberalism was not triggered by the Kennedy assassination, nor was the neoliberal era triggered by the elections of Thatcher and Reagan. These were worldwide trends.

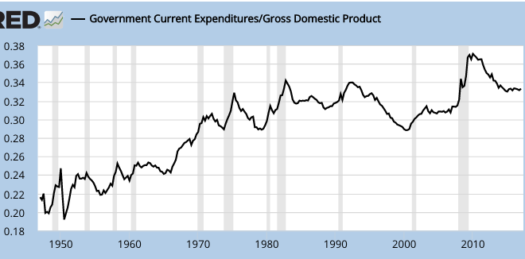

The Aussies have done very well in recent decades, and have a right to be complacent. But the same thing happened in the US. Here is government spending as a share of GDP, which rose sharply after 2000:

I know what you are going to say; “That’s due to special factors—G/GDP rose due to the 2001 recession and 9/11.

I know what you are going to say; “That’s due to special factors—G/GDP rose due to the 2001 recession and 9/11.

There is some truth in that, but it’s not the whole story. G/GDP did not fall back when we recovered from the recession. And indeed both Bush and Gore were promising bigger government than Clinton—the country was getting tired of neoliberalism by 2000. Soon we would have Sarbanes-Oxley, a big new Federal education program, and a massive expansion of Medicare. And that was under a GOP President—once Obama took office we moved even further towards big government. And yet if you read pundits on the left all you hear about is endless “austerity”, which is nowhere to be seen in the data.

The UK was not hit by recession in 2001, nor was it impacted by 9/11. But at almost exactly the same time the Labour Party got tired of austerity, and began rapidly boosting government spending:

You need a trained eye to read these graphs properly. The G/GDP ratio usually tends to be somewhat countercyclical, rising during recessions and falling during booms. The sharp rise in the UK’s G/GDP ratio after 2000 was an exception, and is a tell tale sign that fiscal policy was dangerously out of control.

You need a trained eye to read these graphs properly. The G/GDP ratio usually tends to be somewhat countercyclical, rising during recessions and falling during booms. The sharp rise in the UK’s G/GDP ratio after 2000 was an exception, and is a tell tale sign that fiscal policy was dangerously out of control.

This might suggest that neoliberal reforms require economic distress, so that the public will see the need for changes. But of course the economic distress of the 1930s led to the exact opposite—the rise of statism.

Rather, it seems that neoliberal reforms require both economic distress and a perception that the problem is caused by bad government policies. The stagflation of the 1970s is one example.

Neoliberal reforms can also be triggered when countries are doing poorly relative to their neighbors. Thus back in 2004 the Germans compared their 11% unemployment rate with the 5% rate in the UK, and concluded that excessively high labor costs were the problem. This led to one of the last successful policy reforms of the neoliberal era. Today, those amazingly successful reforms are politically unpopular in Germany

PS. Over at Econlog I comment on the two (rumored) new Fed picks.