Michael Hatcher on NGDP targeting

Marcus Nunes directed me to a recent post by Michael Hatcher, discussing NGDP targeting:

(1) To the extent that future output is uncertain, nominal GDP targeting does not provide an anchor for inflation expectations. Nominal GDP targeting does provide an anchor for nominal spending. What it does not do, however, is provide a clear focal point for inflation or price level expectations. To see this, note that a nominal GDP target of N* will be met when P.Y = N*, where P is the price level, and Y is real GDP. Hence, the central bank should promise to set P = N*/Y, making the price level countercyclical. Since future output is uncertain, there is no fixed point on which price level expectations will gather given a promise to move the price level inversely with output. The same reasoning also applies to inflation, except that expected future inflation will be inversely related to expected output growth under (credible) NGDP targeting. All this matters because having a clear focal point for inflation or price level expectations is crucial for keeping actual inflation low and stable. Indeed, there is good evidence from bond yields that inflation targeting has lowered inflation expectations and reduced inflation uncertainty (see here and here). This would be lost under nominal GDP targeting, putting the economy at risk of higher and more variable inflation.

There are several points that need addressing. A switch to NGDP targeting does not necessarily result in higher or lower average inflation; rather inflation might become more countercyclical. The trend rate of inflation is just as likely to fall, as it is to rise. It’s not even clear that inflation would be more unstable, as inflation targeting is probably not the best way to stabilize actual inflation.

But there’s a far more important issue here. In my view, inflation expectations don’t matter very much; it’s NGDP growth expectations that matter. The so-called “welfare costs” of inflation, such as “shoe leather” costs and the cost of excess taxation of investment income, actually apply better to NGDP growth, for the simple reason that NGDP growth is more closely tied to nominal interest rates than is inflation. So if inflation expectations do become more unstable, that’s actually a point in favor of NGDP targeting, as long as NGDP growth expectations become more stable.

(2) Nominal GDP targeting is not easy to communicate to the general public. Proponents of nominal GDP targeting have argued that it would be easy for central banks to communicate monetary policy in terms of a target for nominal spending. But as I argued in point (1), the problem comes when individuals attempt to forecast the two variables (price level and real GDP) that make up nominal GDP. For instance, the guidance nominal GDP targeting gives about future inflation is minimal, since there are an infinite number of price level and output combinations (or, equivalently, inflation rates and growth rates) which are consistent with any given nominal GDP target. Hence, any inflation rate is desirable, given wild enough swings in output. In such circumstances, central banks would presumably be forced either to deviate from the nominal GDP target (losing credibility) or to specify circumstances in which the target would not apply (big shocks). But then the target itself becomes state-contingent and its simplicity is lost.

I don’t see why central banks would deviate from NGDP targeting in response to wild swings in inflation, because it is NGDP growth, not inflation, that matters. It is NGDP growth shocks that destabilize labor markets and financial markets, not inflation shocks. Indeed there was a positive inflation shock in the first half of 2008, and yet NGDP growth was slowing. In retrospect, it is NGDP growth that should have been stabilized in 2008—that was the much more important shock. Unfortunately, the Fed and ECB paid too much attention to the inflation shock in mid-2008, and as a result monetary policy was too tight.

The public would actually find it much easier to understand NGDP targeting, whereas the public is completely mystified by inflation targeting. They don’t even know what inflation is. The public thinks that inflation should measure the rise in the cost of living, the way we live now. Thus they would include the average amount of money that people spend to buy a TV set in a price index, whereas we actually put in the price of a quality-adjusted TV set, which is vastly different. Even worse, they don’t understand the purpose of inflation targeting. In 2010, core inflation had fallen to 0.6% and Bernanke announced the Fed would try to increase inflation. The public should have jumped for joy; “Great, we are going to get closer to the inflation target of 2%”. Instead there was outrage that the Fed was trying to increase the “cost of living” for Americans who were already suffering from recession.

When the public thinks about “inflation” they tend to implicitly hold their nominal income constant. Thus they wrongly think that inflation lowers their living standard, and they thought Bernanke’s 2010 policy would reduce their real income. Implicitly they equate “inflation” with “supply-side inflation.” But of course the Fed has no impact on supply-side inflation, it can only influence demand-side inflation. And an increase in demand-side inflation (which is what Bernanke was trying to achieve in 2010) would actually increase the real incomes of Americans.

Now let’s assume that in 2010 Bernanke had said that a healthy economy requires adequate growth in the incomes of Americans. Suppose he said that the economy was weak due to slow growth in incomes, and that the Fed would try to generate 5% growth in our incomes. That would have probably provoked much less outrage from the general public than his call for higher inflation. It would also have had the merit of being more accurate, as Bernanke was actually trying to boost demand (NGDP) and he hoped most of the rise would be in RGDP, not inflation. When he suggested the need for higher inflation in 2010, he actually meant that he wanted more NGDP, hoped it would be mostly RGDP, but expected it would also lead to more inflation.

3)Credibility would be strained in the face of demand shocks under nominal GDP targeting. Scott Sumner and others have argued that one benefit of nominal GDP targeting is that it provides flexibility in response to supply shocks. It would not require, for example, that the central bank raise interest rates in response to stagflation: a rise in inflation would be permitted, temporarily, while output is weak. But large supply shocks are fairly infrequent. If we look instead at demand shocks, nominal GDP targeting looks less attractive. Suppose, for example, that the nominal GDP target is 100, but that nominal GDP overshoots to 105 due to the price level and output being higher than expected in the face of a positive demand shock. Nominal GDP is now at the level it should be next year, assuming an NGDP target path that rises by 5% per annum. As a result, the central bank now wants nominal GDP to flatline next year. It is therefore faced with three unattractive choices: keep both inflation and output growth at zero; combine positive inflation with negative output growth; combine positive output growth with deflation. The likely result is that the central bank would not follow through in these circumstances, and its credibility would be eroded. Enough such episodes could reduce credibility to the point where nominal GDP targeting would have to be abandoned.

Once we factor in negative demand shocks and the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates, things look even worse. For instance, suppose that nominal interest rates are near the zero lower bound and nominal GDP undershoots to 95, i.e. 5% below the target of 100, due to a series of negative demand shocks that lower the price level and real GDP. Now, given trend nominal GDP growth of 5%, the central bank would have to promise to raise nominal GDP by 10% next year in order to meet the new target of 105 (=100*1.05). Ten percent(!) – through inflation or output growth, or some combination – when the economy is at the zero lower bound. What central bank can credibly promise that? That would take a massive amount of credibility, probably too much to be plausible in practice.

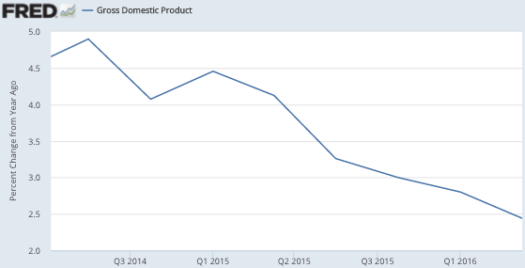

Here I think Hatcher partly misses the point. The main purpose of NGDP targeting is to reduce the severity of demand shocks. For instance, in mid-2008 inflation in the US had risen well above target, and hence the Fed tightened monetary policy, causing NGDP to fall 3% over the next year. This was a powerful negative demand shock, caused by the Fed’s tight money policy. This shock made the financial crisis much worse, and also sharply increased unemployment. Under NGDP targeting the Fed would have had a much more expansionary monetary policy in late 2008, and hence the demand shock would have been much smaller.

Hatcher might reply that even with the best of intentions there would still be negative demand shocks under NGDP targeting, as monetary policymakers are not perfect. I agree. But the make-up required to reach the old trend line would actually be stabilizing under NGDP targeting. For instance, if the Fed makes a mistake and NGDP growth overshoots the target, then they need to gradually reduce NGDP to bring it back to the trend line. Normally a policy of reducing NGDP growth might cause a recession. But if you start from a position where NGDP has overshot the target, then you are starting from a position where output and employment are above their natural rates. So the contractionary monetary policy is actually stabilizing, as it brings you closer to the natural rate. Something like that happened in Australia in 2008, when the economy (NGDP) had overheated. A sharp slowdown in NGDP growth in 2009 did not cause a recession in Australia, but rather brought output and employment closer to the natural rate. So these moves to bring NGDP back to the trend line would actually be less controversial than you might assume, if you simply had looked at the NGDP move without reference to where the economy was relative to the natural rate.

How about the zero bound problem? Ironically, Michael Woodford endorsed NGDP level targeting a few years ago precisely because it does a better job of handling the zero bound problem. When NGDP falls well below trend, it’s hard to reduce real interest rates under an inflation-targeting regime. In contrast, under NGDP targeting you can call for a temporary period of above average nominal growth, which reduces interest rates relative to both inflation and (more importantly) NGDP growth. Now of course there is still the underlying problem of having concrete policy tools that are effective at zero interest rates, and I’ve written zillions of posts on options for doing so. But for any given policy tool, it would be more effective at the zero bound under NGDP level targeting (or price level targeting) than under inflation targeting.Here’s another way of thinking about it. Asset prices are closely linked to changing expectations of two or three-year forward NGDP. In late 2008 and early 2009, those expectations plunged, and this sharply depressed asset prices—also hurting the balance sheets of highly leveraged banks like Lehman Brothers. Under NGDP targeting, two or three-year forward NGDP expectations are more stable, and hence asset prices are more stable. That would tend to reduce the severity of demand shocks. In modern macro models, current moves in aggregate demand (NGDP) are closely linked to future expected changes in demand.

To summarize, the best argument for NGDPLT is not that it handles “shocks” better than other regimes such as inflation targeting, but rather that it recognizes that most so-called “shocks” are simply bad monetary policy, and NGDPLT makes for a more stable economy by reducing the frequency and severity of those monetary shocks.

PS. I’ve been catching up on old podcasts from David Beckworth, which I missed the first time around. This morning I listened to the one with Ramesh Ponnuru, which does a really nice job explaining the intuition behind NGDPLT. The podcast with George Selgin provides another excellent perspective on the basic idea.