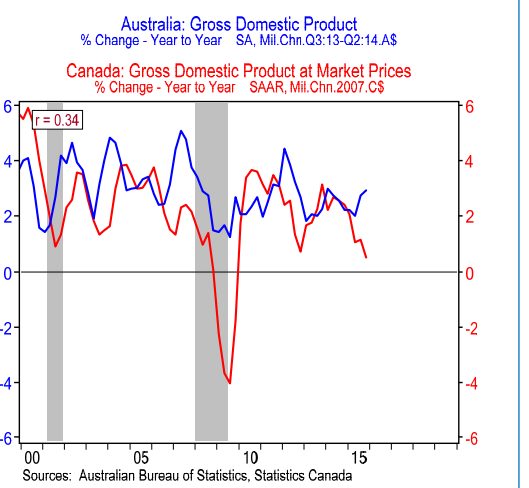

Has the Fed “assumed broad responsibility for nominal output growth”?

Deutsche Bank says yes:

The Fed’s dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability implies substantial oversight of the private economy. We develop a proxy for nominal private GDP growth, perhaps the broadest measure of private sector activity, and decompose this proxy into two segments, one that is explicitly within the scope of the dual mandate and one that is not. Weak nominal private growth in the present cycle has been almost entirely due to the latter, in particular the abysmal trend in productivity. We conclude that while a narrow reading of the Fed’s dual mandate might suggest that it is far behind the curve in terms of rate hikes, the Fed has favored a very cautious approach because it has implicitly assumed broad responsibility for nominal output growth. As the productivity slowdown is unlikely to get resolved in the near term, we expect the Fed to remain on hold through much of this year, and possibly into next year.

I highly recommend Gregory’s Clark’s review of Robert Gordon’s book on the growth slowdown. He does a nice job of explaining why productivity growth is going to remain low for the foreseeable future:

The core of Gordon’s pessimism about future technological advance is that the modern US economy is now heavily based around services, accounting for 80 percent of output. Manufacturing, traditionally a sector with higher efficiency advance, has shrunk to 12 percent of the economy. . . .

A surprising share of modern jobs are the timeless ones of the pre-industrial era— cooking, serving food, cleaning, gardening, selling, monitoring, guarding, imprisoning, personal service, guiding vehicles, carrying packages. Food production and serving, for example, now employs significantly more people (9.1 percent) than do production jobs (6.6 percent). One in ten workers is employed in sales. The information technology revolution to date has left these jobs largely untransformed. Workers in these types of jobs in Europe in 1300, if transplanted to modern America, would need little retraining.

Even outside services, we can find jobs with no gain in productivity since the Industrial Revolution. Builders’ price books in eighteenth century London show the rate at which bricklayers laid bricks in house construction. In 1787 this was 75 bricks laid per hour. For modern England the rates are lower, 225 years later, at around 50–70 per hour.

Combine slow productivity growth with at most 2% inflation and a working age population that’s growing very slowly, and you are left with 3% NGDP growth and very low interest rates for as far as the eye can see. Get used to it.

HT: Federico