Bernie’s Nordic fantasy

Progressives like to point out (correctly) that the GOP tax plans are sheer fantasy. But as I often point out, talking politics immediately lowers your IQ by 25 points. And I’m afraid that when progressives start talking about Bernie Sanders they completely lose touch with reality. They say, “He’s not really a socialist, he just favors the Scandinavian economic model.” But they don’t seem to know any thing about that model.

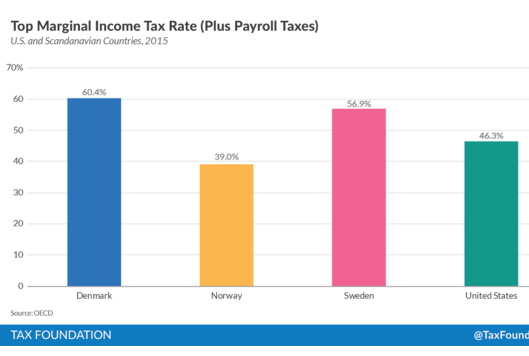

Let’s look at taxes, for instance. Here are the top rates on income (plus payroll) taxes:

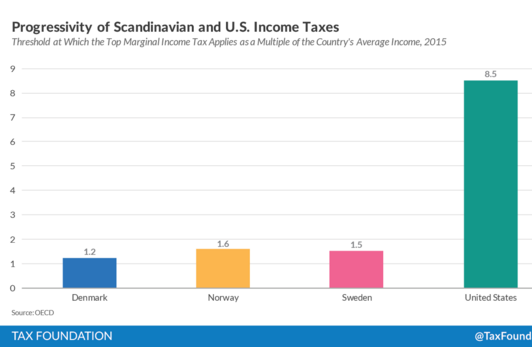

And then here’s an indicator of progressivity:

In Denmark the top rate kicks in at 1.2 times average income. In the US that would be around $60,000.

In Denmark the top rate kicks in at 1.2 times average income. In the US that would be around $60,000.

And then there are the VATs:

Denmark collects about 9.6 percent of GDP through the VAT, Norway collects about 7.8 percent, and Sweden collections about 9 percent of GDP. All three countries have VAT rates of 25 percent. The United States does not have a national sales tax or VAT. Instead, states levy sales taxes. The average rate across the country is about 7 percent. The much lower rate only collects about 2 percent of U.S. GDP in revenue.

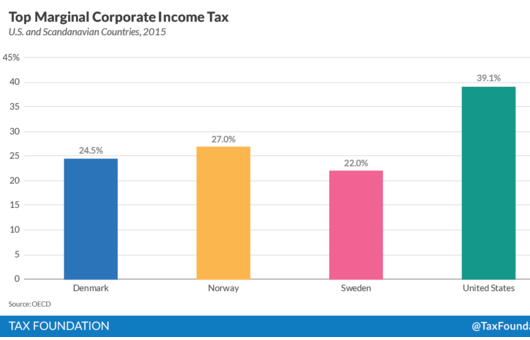

Bernie Sanders says he doesn’t want to raise taxes on the middle class, rather he wants the rich to pay more. Later he grudgingly concedes the middle class would pay a higher payroll tax for the nationalized heath care, but still doesn’t mention the 25% VAT. Nor does Bernie mention that the Scandinavian countries have far lower corporate tax rates than America:

Nor does he mention this:

Nor does he mention this:

Finally, it is worth noting that the only Scandinavian country with an estate or inheritance tax is Denmark.

So the only way to finance a Nordic economic model is with massive (and regressive) taxes on the middle class, because that’s where the money is.

What about those 90% tax rates from the Eisenhower era, that you often read about? There’s a reason the Nordics don’t use that policy, they collected very little revenue.

And I haven’t even mentioned that the Nordic countries are really big on privatization and deregulation. How often do you hear progressives calling for those things? When was the last time you heard a progressive advocating Sweden’s 100% nationawide school voucher program?

And it’s even worse. Sanders doesn’t tell us whether he likes the Swedish model of 1990, or the Swedish model of today? I’m pretty sure that back in 1990 he was telling people that he loved the Swedish model. But that model failed, leading Sweden into economic crisis. It responded by dramatically downsizing its government relative to 1990 (admittedly it’s still very big in absolute terms.) But I never hear the Sanders supporters telling us whether they like the 1990 socialist Sweden, or the 2015 neoliberal version? Ditto for Denmark.

And they never tell us how this European social welfare state is supposed to work in a big diverse continent like the US, when it doesn’t even work in a big diverse continent like Europe (especially not in Eastern and Southern Europe.) Matt Yglesias says that places like Sicily are poor and dysfunctional because they have a bad culture. I don’t know if that’s right, but let’s say the progressives are right to “blame the victims” of poverty in Europe. Can we really be confident that our many diverse cultures are so superior to Sicily and Greece and Naples and Bulgaria and Romania? Can we be sure that the poor Hispanics of East LA, the poor Native Americans of western South Dakota, the poor African Americans of Detroit and the poor whites of West Virginia have Nordic-style cultures, and not southern and/or Eastern European-type cultures. Seriously? The Latin American country that tried the high tax model is Brazil. Does the US ethnic makeup remind you more of Brazil or Denmark?

Sorry, but I can’t take seriously anything progressives write about Sanders. Those on the left are correct in ridiculing the tax ideas of Trump, and even the tax plans of the more “serious” GOP candidates do not raise enough revenue. I get that. But when evaluating their own side of the spectrum they lose all touch with reality. Here’s Paul Krugman:

So now we have candidates proposing “wildly unaffordable” tax cuts. Can we start by noting that this isn’t a bipartisan phenomenon, that it’s not true that everyone does it? Hillary Clinton isn’t proposing wildly unaffordable stuff; Bernie Sanders hasn’t offered details about how he’d pay for single-payer, but you can be sure that he would propose something.

Seriously? Sanders says he wants a Scandinavian style welfare state, without raising taxes on the middle class? And we are supposed to treat that seriously? Then the left wonders why working class blacks and Hispanics are not flocking to Sanders. Maybe those minorities are smarter than then these puzzled pundits assume. Maybe a Hispanic family with two people each making $30,000 to $35,000 doesn’t want to face a 60% income tax, plus a 25% VAT. Maybe they moved from some place like Brazil, and know what happens to all that money once a non-Nordic government gets their hands on it. Maybe they’d rather spend their own money. Someone should go into working class black and Hispanic neighborhoods, with all the data on income and sales tax rates in Denmark, and ask people if they also want to pay those rates. You might be surprised by what you find.